As we have seen (read The Frank Shaffer Story), the chance connection between Dr. Carlos Booth’s great nephew Frank Shaffer and Paul Wilson occurred via comments in VeloceToday. This prompted Paul to pay Frank a personal visit. Thanks to Frank, images from his family photo album illustrated Paul’s yet unpublished story about Dr. Booth and his horseless carriage. A complete, nicely published genealogy gave Paul the ability to trace the connections to the Shaffer family resulting in the final product you see below. [Ed.]

Story by Paul Wilson

Photos from the Shaffer collection

Dr. Carlos Booth had never liked horses. He was an energetic, restless man, who had found that obstacles encountered in most aspects of life yielded quickly to the application of energy and impatience. The problem of making his rounds with a horse, however, did not. When he was in a hurry (Dr. Booth always was) the horse would be feeling tired. When it was needed in an emergency it often was found to be suffering from harness sores or bad feet. Its feeding and care took a lot of time. It could not be left outside a patient’s house with any certainty that it would be there when he came out. And there was nothing, apparently, that Dr. Booth could do about any of this.

Dr. Booth’s brother-in-law, Frank J. Shaffer, (1852-1927) and his wife Luna in a horse and carriage probably around 1910.

And horses were dangerous. In 1891 a terrified horse dragged the carriage with his father-in-law and his wife’s two sisters in front of a freight train. Dr. Booth’s medical specialty was trauma–he was in charge of the Youngstown City Hospital’s ward for steel plant victims–and he arrived in time to save young Ella, but the other two were killed. Then in June of 1895 Booth and his wife were out for a drive in their buggy when the horse took fright at something on the road and bolted off through traffic at a full gallop. The accident took the horse to its death, placed Mrs. Booth in the hospital on the danger list, and started the doctor thinking of a way he might replace his horses for good.

By a coincidence, it was in the same month as Dr. Booth’s runaway that the Paris-Bordeaux race was held in France. Dr. Booth read reports of the race, and saw instantly that an automobile would be an ideal substitute for a horse for use in his practice. Streetcars, loud noises, and bits of paper flying in the wind would not cause its iron heart to beat more quickly. It would sit patiently in one spot for hours, and not be tempted to wander off to graze in a nearby field. It would need to be fed only when working. In short, it was rational, and Dr. Booth liked that. And if it could be made to work anything like as well as the car which won the race in France, it could carry the doctor twice as far every day as the horse could, and could be driven unmercifully without arousing the wrath of the Humane Society.

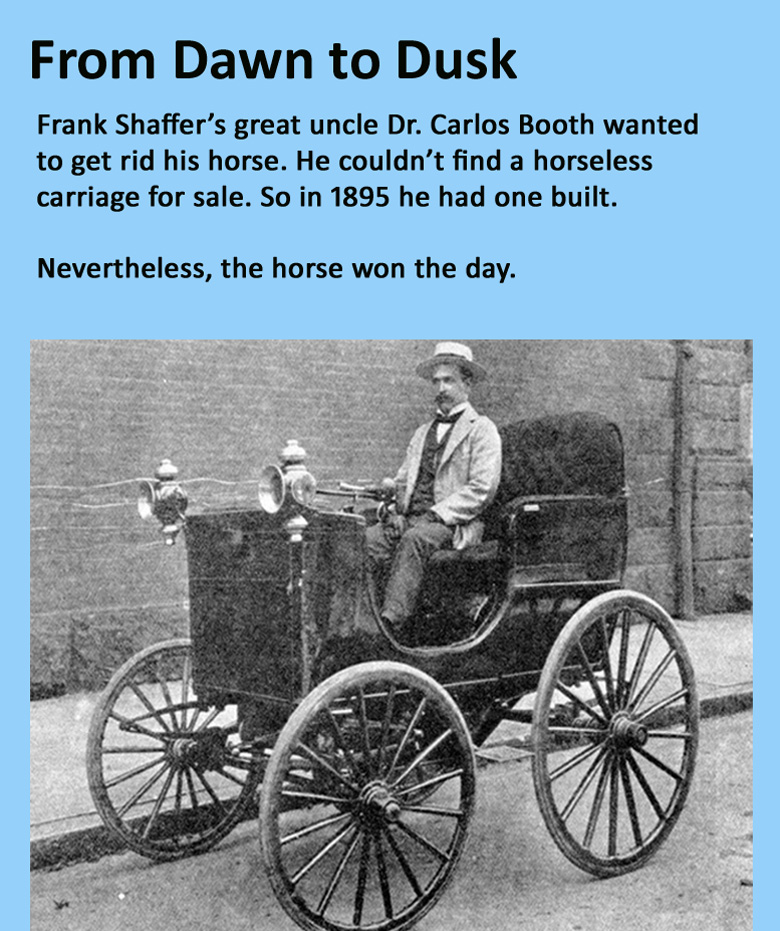

As far as Dr. Booth knew there were no automobiles available in the U.S., so he had no choice but to build one himself, which he set about doing with characteristic dispatch. He drew up a general plan of the vehicle and arranged with W. Lee Crouch, of the Pierce-Crouch Engine Co., in New Brighton, Pennsylvania, to design and build an engine, and with the Fredonia Manufacturing Company of his home town of Youngstown, Ohio, to build a body. With the doctor barking at their heels like a terrier, Crouch et al built the car with remarkable speed, and though it was not ready in time for the Chicago Times-Herald race in November, it was making test runs with satisfactory results before the end of the year.

A photo that appeared in Automobile Quarterly’s “The American Car since 1975” (1971). The caption read “Dr. Carlos Booth of Youngstown, Ohio, used a 3 hp W. Lee Crouch-built engine, but his car wasn’t ready in time for the contest.”

The first race in America

By the time the roads were clear and dry in the springtime the vehicle (which Booth called a “cab”) had been improved to the point where it could be used by the doctor every day for making house calls. When its one-cylinder engine was turning at 500 r.p.m. it could propel the 1040 lb. vehicle at 16 m.p.h., according to Booth, and he amused himself by taking Youngstown businessmen on demonstration rides. His confidence was so great that the decided to enter his machine in the race sponsored by Cosmopolitan magazine in May. He let it be known that he thought his “cab” to be “about as serviceable a motor wagon as has yet been produced.” (According to Taken by Speed: Fallen Heroes of Motor Sport and Their Legacies by Connie Ann Kirk, the Cosmopolitan Magazine race was the second auto race in the U.S. and held on May 30th, 1896. The 52 mile event went from the New York City Hall to Irvington-on-Hudson and back.)

The Cosmopolitan race was a humiliating experience. Dr. Booth shipped his car to New York and finished the first half of the 52 mile course without incident, but on the way back his car broke down and had to be towed home. Dr. Booth was not a graceful loser. Other than a flock of Duryeas, his car was the only one that started, and the doctor felt with some justification that its performance in traveling over most of the route deserved some award. The rules stated, however, that a car must finish the course to be eligible for part of the $3000 prize money, and the organizers held to the rules, so Booth got nothing. He protested loudly and unreasonably, and when asked if he would enter a race scheduled later in the year in Providence, Rhode Island, he wrote angrily that he would not,

…as I am suspicious of the good intentions of your organizers of Eastern races after being treated as Mr. Brander and myself were . . . they do these things differently in Chicago. There something like justice was done.

Dr. Booth entered no more races, but he continued to use his car regularly, and made numerous improvements to it. Since a doctor must travel in all weather conditions, Booth decided that a closed body would be a desirable feature, and had one built. This was surely the first closed body on an American-made passenger car, and was not widely imitated for another eight or ten years. Booth also worked on the engine, and by the fall of ‘96 he claimed a top speed of 20 to 25 miles per hour. Although the car continued to suffer from transmission problems, it was clearly practical for regular use the way it was. In the late fall of ‘96 Booth told The Horseless Age,

I am using it every day and night. Have made all my night calls with it since last July, so you understand it is a real live thing.

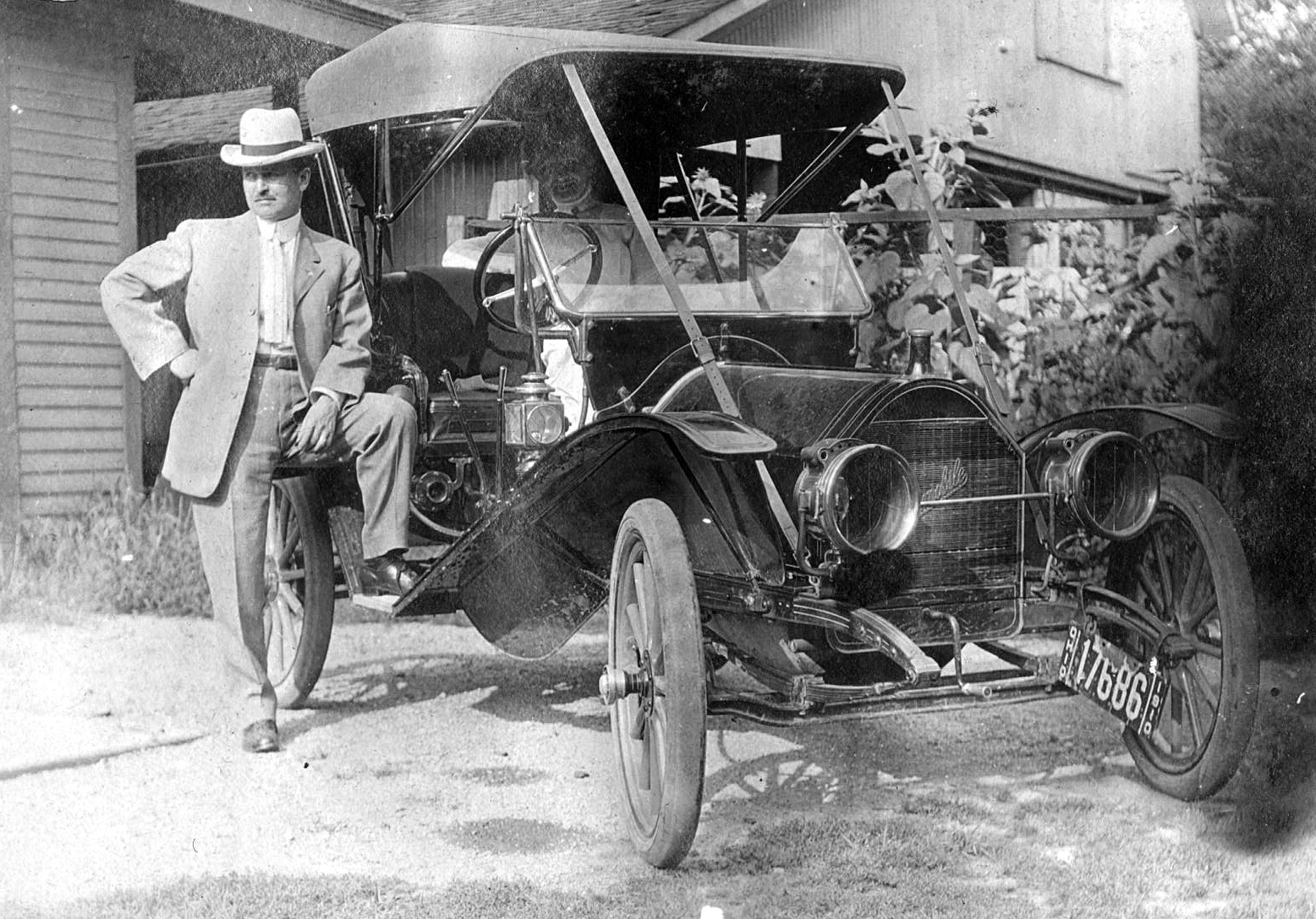

Dr. Booth and his 1910 Hupmobile. His wife Pluma is sitting in the car, barely visible through the glass windshield.

Dr. Carlos Booth, who had gone to the trouble of building an automobile to rid himself of the vexations of horse management, found to his annoyance that the use of his “cab” for his rounds in Youngstown actually increased his problems with the detested animal. The vehicle occasioned such a commotion among the horses that he was not able to go anywhere without having to stop and lead some terrified team past him. For Dr. Booth, who hated delays of any kind and who had no patience with animals, this was maddening. He removed the roof from his car, hoping that this would make the car less frightening in appearance, but it made no difference. One way or another, the doctor could not get away from horses: they caused him even more trouble when he did not drive them than when he did. He dreamed of a day when he would no longer be tormented by horses, but that day had not yet arrived. In the meantime he took the easier way out: in early 1897 he sold his car to a New Yorker and hitched up his buggy again. A few years later, when cars no longer caused such a fuss, Booth became an enthusiastic motorist. But it would be 125 years before the story of the doctor who hated horses was finally published.

Paul Wilson

Paul Wilson’s car collection ranges from post war Alfas to a Lamborghini Miura through Can Am race cars, but Wilson is also interested in horseless carriages and had previously written a book about the development of automotive styling called Chrome Dreams.

Paul Wilson not only owns a Lamborghini Miura, but at the other end of the scale, a rare Marot-Gardon. In his book “Chrome Dreams” Wilson deftly describes the rapid – and interesting changes in the automobile between 1899 and 1094. We asked him to do the same using Jonathan Sharp’s images from the 2016 Brighton Run. Photo of Wilson’s Marot-Gardon by the Editor.