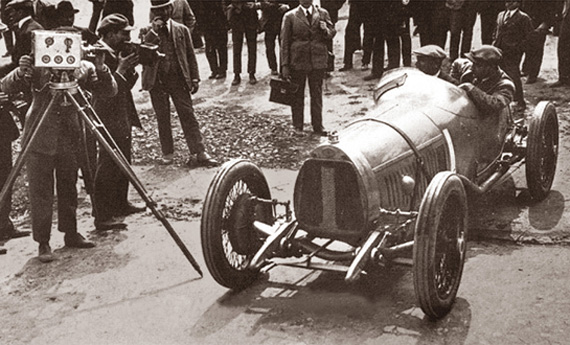

The Delage Bequet at Kop Hill, 2013. This car was originally built as a 2 liter V12. The car was rebuilt for Maurice Bequet and was fitted with a 12 Liter Hispano Suiza V8 aero engine in 1926. The runs are not timed but this did not seem to deter Boswell's spirited run. Jonathan Sharp photo.

Those who have ridden as co-pilot say that a desire to survive is their dominant emotion.

By Alexander Boswell, owner, driver

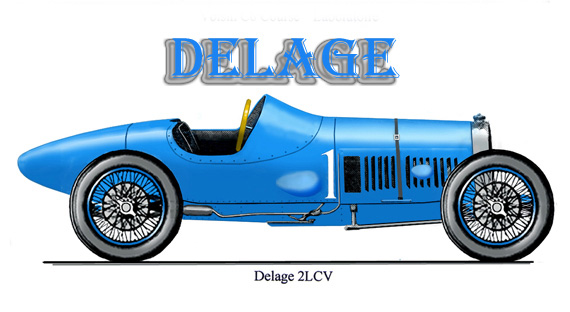

It’s an amazing experience to drive any car built for Grand Prix racing. One knows that relentless effort, concentration of resources, and usually a huge budget have contributed to the creation of something technologically remarkable. Despite its 90th anniversary, the 2LCV Delage still encapsulates all these elements. In 1923 this was the only entry from the stable of the Delage company, and therefore it represents the pinnacle of the technology of the time. This car was driven in the French GP by René Thomas, the Sebastian Vettel of his day.

The Delage was raced in 1923 with the world’s first V-12 racing engine. At 2 liters capacity, each piston was no bigger than an eggcup. It was a complex engine, and by our standards today, only moderately powered.

That’s why the addition of a 12 liter Hispano Suiza out of a SPAD fighter in 1925 created such a sensational machine. The brilliance of the finest 1923 racing chassis was mated to the effortless power of a big low-revving engine. This was former test-pilot Maurice Bequet’s inspiration….and it’s still causing a sensation to this day.

The car is delicate in every way apart from the motor. Once those great pistons start moving and the twin-plug ignition fires the mixture, the beast is dominated by the engine. Smoke and flames emerge from the stub exhausts, and the noise is a sharp low bark. In the cockpit the engine feels frighteningly alive. Let out the clutch and the narrow wheels spin uncontrollably. In first gear it’s doing 30mph whilst the engine runs at idle. Second gear is good for nearly 100; third is geared at 65mph per 1000rpm, and over 150 mph is possible.The cockpit is tiny. There is enough room for the pilot, but the passenger seat is reserved for only a small co-pilot, who has to slide in, cant over his or her hips and wind one leg over the other. Strangely, other sensations soon overwhelm any of feelings of discomfort; people say that a desire to survive is their dominant emotion. The run up to the start line is a struggle. People crane forward and around the car to get a proper look at this extraordinary vehicle. The temperature starts to rise inexorably. There are only two or three minutes available to get to the line and away before the engine boils over. Any hesitation by other cars going up to the start is a source of stress.

A long and truly fascinating story is foretold on the wheel spoke of the Delage. Jonathan Sharp photo.

At last the Delage is at the line. We have been watching the departure of the preceding competitor. It’s essential he gets well up the hill before we launch. Depress the clutch. Select first gear in that massive gearbox by pushing the lever to the left and forward. Goggles over the eyes. The engine revs have risen to 1800 rpm. The flag drops, and all hell breaks out. There is an explosion of noise, flames, smoke,and fumes. Despite careful balancing of engine revs, the wheels spin wildly and fight for grip, leaving a black rubber trail of over 50 yards. The acceleration is visceral, terrifying. The engine has taken control. There is nothing that can be done but hang on as the car rockets away. The revs rise to 2200 in a flash and it’s time to take second, a fierce lunge to haul the heavy gear lever back and across to the right. It’s hugely physical to move it fast enough. Sometimes the gears mesh first time, sometimes it takes another try. We’re now already flying up the hill, but if anything the car is accelerating even harder. The scorched rear tires have softened and are gripping at last, the engine has dropped into the sweet spot of its torque curve, and the car feels light and controllable. We are doing over 80 mph already and despite the steepness of the hill, the gain in speed is remorseless.

The first bend comes up. A right-hander. A light lift and a touch on the brakes to steady the car and wash off speed. Aim at the apex. Don’t try steering. Just adjust the throttle. The rear of the car lunges to the left, sliding sideways from the loss of grip. The front remains planted, now pointing correctly for a fast exit. Accelerate hard. The power comes in like a tsunami. We are well over 80 mph again, but the inside rear wheel is now spinning, scrabbling for grip and slewing the car further sideways in an instant. This is a dangerous moment: lifting off will bring disaster. The rear of the car can overtake the front quicker than any human reaction can control. The only answer is to hold the throttle down and go with the slide, waiting for the car to settle and stabilize. It only takes an instant and it’s done. The car leaps on up the hill, unruffled and unconcerned, the hedge sides now a frightening blur as the rough road pulverizes the front suspension.

We fly through the finishing post at enormous speed. We now have to gather the beast in. Like a bolting horse, the Delage is reluctant to slow down. Marshalls are waving. Cut the throttle. The tiny brakes must now play their part. A hard stab. Nothing seems to happen. A long hard pressure. Gradually the car begins to slow. A grinding howl emerges from the brakes, dissipates through the suspension and into the car. Pull the outside handbrake gently upwards. The speed washes away. Clutch in. Slow to walking pace and arrive at the top of the hill, trying to look unconcerned. Time to start breathing again. The ascent has taken only a few seconds, and despite the vicious speed, the climb felt like it was in slow motion.

In 2012 an amateur timekeeper stated that the fastest car of all on the hill was the M12C McLaren. The second fastest, and not much slower, was the Delage Bequet.

From Whence Came this Monster

Above drawing and text by Gijsbert-Paul Berk

Encouraged to take part in the eagerly anticipated 1923 French Grand Prix at Tours, Louis Delâge asked his chief engineer Charles Planchon to design a new engine for their prototype 4 cylinder Grand Prix car. Delage wanted a something conventional; Planchon was determined to use his V12 design. The decision to adopt the V12 was taken far too late, in October 1922, allowing only weeks of development before the 1923 Tours Grand Prix.

Planchon designed a complicated V12 machine, with two blocks of six cylinders at 60 degrees and on each of the cylinder heads two overhead camshafts. The crankshaft had seven roller bearings. Four Zenith carburetors were mounted on the inlet manifold to feed the beast, and two Scintilla magnetos assured the ignition of the twelve spark plugs. On the bench it developed 120 bhp at 6200 rpm. It was an engineering masterpiece and beautifully finished as well. Engine power was transmitted to the rear axle by a multiple disc clutch and a four-speed gearbox. The new 2LCV (2 liters/Course,/V12) had a ladder chassis with beam axles at the front and the rear, all fitted with leaf springs and double friction dampers. Planchon managed to get one 2LCV ready for the French Grand Prix, but with little time to spare for proper testing. According to Alexander Boswell, testing did indeed take place with René Thomas at the wheel. “He describes his testing sessions, most of which ended with the car in a cloud of steam! ‘Le radiateur etait a la vapeur et avec l’huile on pouvait faire des frites.’ Indeed, it was the ‘chauffage’ which proved to be the car’s Achilles heel. René Thomas suggested to Delage that the car should be pulled from the event, but Delage was keen to see it perform.”

During the first laps of the race at Tours, Thomas showed that the Delage was fast and even led at one point. Therefore Louis Delâge and René Thomas were bitterly disappointed when the car had to retire in the sixth lap. “The official reason given for retirement was a ruptured fuel tank, but this was purely manufacturer-speak in order to avoid mentioning a flawed mechanical component,” noted Boswell. Delâge blamed Planchon and fired him. In his place he appointed Planchon’s assistant Albert Lory. To increase power and reliability Lory made some minor changes to the original design.

Three more cars were made with the upgraded engine, and Delâge entered the four of them in the 1924 European Grand Prix at Lyon. Two 2LCV Delages driven by Albert Divo and Robert Benoist finished in second and third place. In 1925, the 2LCV was equipped with two Roots superchargers. Our subject car was fitted with the Hispano V8 in 1925. It was entered in this form in the Sebastian Grand Prix of 1926 and thereafter performed in a number of events with the name “Coty Special.”

Next week, Driving the Napier Railton.

Very interesting article about the Delage with the Hisso motor. It typifies the aero-engined specials such as the Fiat “Mephistopheles” that appeared during this period. It must be a real beast. I think that if you check, you will find that the first V12 racing motor for automobiles was designed and built by Packard in the U.S. It was called the “299”, displacing 4.9 Liters and was SOHC. The car was first run in 1916 at Sheepshead Bay. Ralph DePalma drove the car in numerous races. It was, allegedly, sold to someone in Italy and is credited with inspiring Enzo Ferrari to build his V12 motors after seeing/hearing the car run in an event in Italy. The car seems to be lost to us now. Maybe the motor is powering an Olive oil press in the back streets of some small Italian village now.

All interesting stuff, and well done to everyone who has had a hand in keeping this car alive. There was only one real highlight in it’s subsequent career; by 1926 with the Hispano engine it was entered in the GP de Provence as the Béquet Spéciale but did not start. It apparently did practise at the Spanish GP but took no part in the race.

At the Grand Prix de La Baule in August 1926 Roland Coty came third in the by then renamed Coty Spéciale behind Louis Wagner’s V12 Delage with Charles Montier second in a Montier-Ford (more on that one later).

In October that year it was entered for the GP de Salon at Monthléry but the race was rained off and a series of demonstration runs were all they could manage, this time driven by Christian Dauvergne.

It then scored a second in class at a hillclimb near Paris, but it seems it did not compete again, at least at Grands Prix or significant international events, before the engine was used in the thirties to rebuild an old SPAD aeroplane.

Roland Coty was a wealthy international playboy from the Coty perfumes family and indulged in polo, sailing as well as racing cars. His father François already had an expensive taste for collecting high class automobiles of the day and his favourite brand was Hispano-Suiza, maybe this had some bearing on his son’s choice of race car?

Not Receiving e-mail in response to application. Longtime admirer & fan.

Wish to pay Premium. Often access VT from office; not able to pay that way.

Can you please check ? Not in Bulk Mail. M. Sayers