By David Beare

From the VeloceToday Archives, November 2013

It is unlikely that Louis Delagarde, the designer of Panhard’s flat-twin engine, could have foreseen the scale of competition successes his diminutive power-unit would achieve when he began work at his drawing-board during the dark days of World War II.

Delagarde’s brief from Jean Panhard was to create a small-capacity, simple, lightweight engine to power and equally simple, lightweight economy car which could eventually be sold to French motorists come peacetime- whenever that might be. At the time an invincible Nazi Germany was offering the world a one thousand-year Reich so the signs were not at all promising. Delagarde was a life-long motorcyclist and recognized the inherent advantages of horizontally-opposed pistons (balance) and air-cooling (simplicity) – much as had Ferdinand Porsche with the KdF-wagen, aka the Volkswagen Beetle, in 1934.

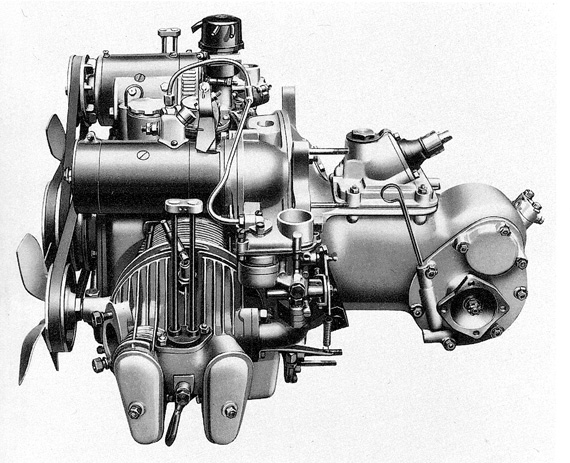

Additional wartime problems to be solved when drawing up Panhard’s new engine included scarce and poor-quality materials such as gaskets, white-metal for bearings, spring-steel wire for valve springs and lubricating oil. Delagarde had to design his way round these limitations and in so doing came up with a unique series of solutions. “Run” crankshaft bearings were a common occurrence so his solutions were roller-bearing rod big-ends with ball-bearing mains, the unbreakable heart of Panhard’s engine. The rod roller bearings were a new design which incorporated small inverter rollers between load-bearing rollers, so everything turned in the same direction, allowing sustained high revs- something future race car builders would much appreciate. Other advantages were low friction losses and oil quality not being so critical with roller and ball bearings, though manufacturing costs were unfortunately much higher than with conventional bottom-ends, as would be replacement crank & rods assemblies when they eventually wore out.

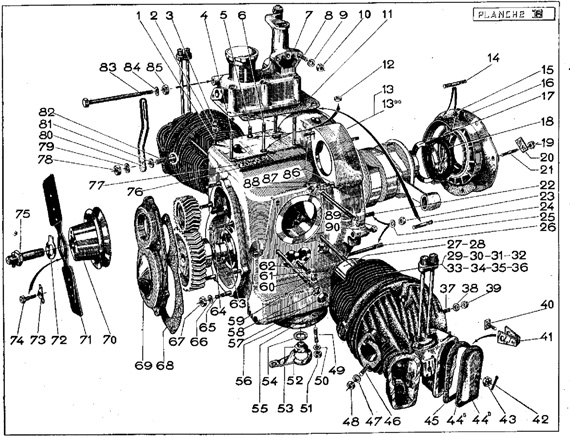

Engine and transmission from 1946, though twin carburetors illustrated were never fitted by the factory (The Automobile Engineer).

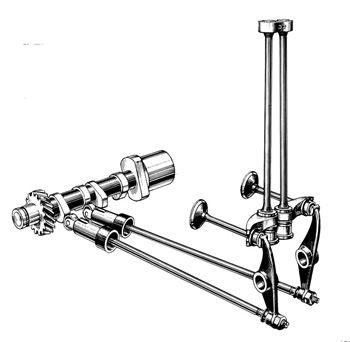

Head-gasket failure- again very common- was eliminated by the simple expedient of using cylinders without detachable heads. The absence of mating surfaces for gaskets meant large valves in hemispherical combustion-chambers could also be used, maximizing gas flow. Unreliable valve-gear had long given engine designers headaches (one reason Panhard had used Knight sleeve-valves since 1910), with breakages of helical-wound coil valve-springs or valves being commonly responsible for many a wrecked engine. Delagarde bypassed most of these problems in a unique way, by using unstressed slim torsion-bar valve return springs. The weight of the valve-spring itself did not move up and down with the valve, reducing inertia loadings and valve-float at high revs. The torsion-bars were linked at their free ends, thus increasing closure pressure on the shut valve when the other opened.

Early Dyna X torsion-bar valve-springs exposed above the cylinder heads (Panhard factory archive/RTA).

Almost the whole engine and gearbox casings were made of high-grade aluminum castings, a material plentiful because of wartime aeroplane production, which cut weight down considerably. Panhard’s economy car was from the outset designed to be front-wheel drive, so the engine/transmission/final drive assembly was conceived as a compact whole – another benefit to sports and competition-car builders, though they were then stuck with fwd, often a disadvantage on race-tracks.

In designing his way round technical limitations of the time, Louis Delagarde had come up with a small 610cc economy-car engine, originally rated at just 2 2bhp @ 4,000 rpm, possessing all the attributes of a competition-pedigree power-unit. It was not long before race-car engineers noticed.

ON THE TRACK

Two of these engineers were Charles Deutsch and René Bonnet. Deutsch and Bonnet had a common passion, motor-racing, but otherwise could not have been more dissimilar. Charles Deutsch was a short and short-sighted Civil Engineering graduate of the École Polytechnique and a self-taught enthusiast in vehicle aerodynamics, while René Bonnet was tall, urbane and a skillful mechanic & competition driver. The two men had met in 1932 and got on well, their shared interest in racing led them to build a Citroën Traction-based sports-racing car, which they campaigned with limited success. After the war they persisted with Citroën-based fwd sports and racing cars, building a single-seater 2 liter car for Formula 2 races in 1948 and entering two ‘tanks’ in the 1.5 litre class at Le Mans in 1949 (one finished 16th) but Citroën disliked “les bricoleurs de Champigny” ( the DIY amateurs from Champigny) and forbade Deutsch & Bonnet from using the company’s engines.

Panhard’s Dyna X84 all-aluminum-bodied saloon was introduced in 1948 and astonished motoring journalists and customers alike with its extraordinarily high performance from just 610cc’s. Rally drivers were soon winning 750cc classes in Panhard Dynas and Deutsch & Bonnet quickly grasped the competition potential inherent in Panhard’s flat-twin.

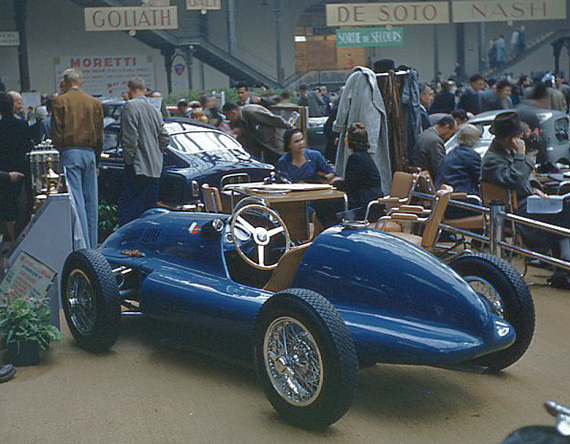

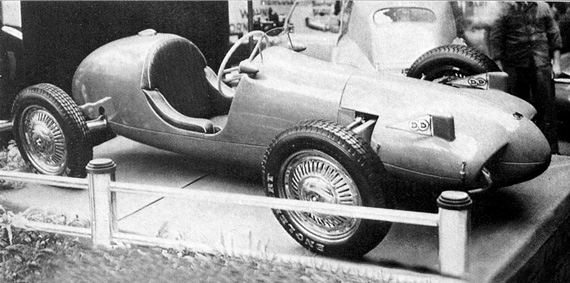

In 1950 the FIA adopted a 500cc Formula 3 single-seater class which had become a great success in Britain, with the likes of Cooper, Keift and Emeryson cars using rear-mounted motorcycle engines such as Norton and the JAP Speedway to power their tiny race-cars. The class became the training-ground for a whole generation of drivers who rose to Formula 1 and worldwide fame. Deutsch and Bonnet saw an opportunity to introduce similar small-capacity Formula 3 single-seaters in France and built a simple race-car based around a box-section tubular chassis with a modified 500cc Panhard Dyna X engine and transmission and Dyna dual transverse leaf-spring front suspension. The rear end was so light a simple dead-axle with angled trailing arms did the job. Vastly different roll stiffness’s meant the inside rear wheel on most corners was at least 4 inches off the tarmac, leading Deutsch to describe a cornering Racer 500 as “un chien qui pisse”, a dog peeing.

Though highly successful on home territory, the fwd D.B. Racer was not very competitive against mid-engined English Formula 3 cars on European race tracks; nevertheless it served the same purpose in training a generation of aspiring Formula 1 drivers including Alfonso de Portago.

The 2.5 Liter unblown Formula One went into effect in 1954, and one of the lesser known provisions was the alternate use of a supercharged 750 cc engine. One of the few firms to try to compete in this manner was Deutsch Bonnet, who dusted off the old Monomille and upgraded the Panhard Dyna engine with a supercharger. But the power to weight ratio was only about 250 per ton, while the 2.5 liter cars were good for 400 per ton. French Porsche and DB driver Claude Storez raced the car at Pau in 1955, but it was too under-powered to be effective. Photo by Gerald Vack.

Not only were Deutsch & Bonnet building Racer 500s in their primitive, cold and cramped workshops at Champigny, they set about designing and building Panhard-powered sports-racing cars for the fabled Le Mans 24-hour endurance race, which were to replace the larger and heavier Citroën-powered cars they had entered in the first post-war race of 1949. The Lachaize/Debille 1500cc Citroën-engined D.B. ‘Tank’ finished 16th out of 19 finishers but the equivalent Deutsch/Bonnet car expired after 175 laps.

One of the D.B.Citroën cars entered for the 1949 Le Mans 24-hour race. (Derek Fritz/ photoIMAGination).

For the 1950 Le Mans the pair entered two ‘barquettes’ (meaning a small boat-shaped pastry or tart!). Number 58 was driven by Bonnet and Élie Bayol and finished 23rd, initiating a very long pedigree of successful Panhard-powered Le Mans racers. The second D.B. Panhard entry, no.59, driven by Guyot/Chassaut, was eliminated in a crash during the second hour.

D.B. Panhards were not the only Panhard-powered competitors at the 1950 Le Mans race. One place ahead of the Bonnet/Bayol D.B. in the finishers list came number 52, a Monopole X84 ‘Tank’ driven by Jean de Montrémy and Jean Hémard which won the Index of Performance, while further down the finishers list featured the Lachaize/Debille Panhard Dyna X84 Sport, the Gaillard/Chancel Callista RAN and the Eggen/”Escale” Panhard Dyna X84 saloon. Two Panhard -powered non-finishers were also listed; the Lapchin/Plantivaux X84 Sport and the Savoy/Dossous Monopole X84 ‘Tank’.

1950 D.B. Panhard 610cc barquette bodied by Antem as raced at Le Mans 1950 (Derek Fritz/ photoIMAGination).

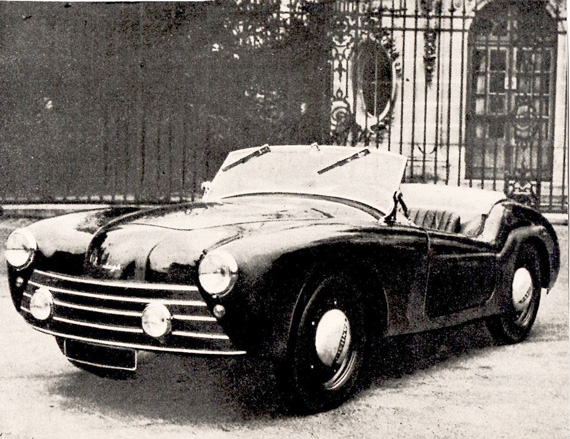

From the number of entries at Le Mans in 1950 it was clear that Panhard’s flat-twin engine and transmission ‘package’ suited numerous small-scale sports-racing car builders in France. It was light, compact, powerful for its size and above all reliable and strong. The 610cc Panhard-engined cars were literally driven flat out for 24 hours, proof if ever it was needed of the inherent strength in Louis Delagarde’s little engine. Jean Panhard and his associate Etienne de Valance were also keen to supply special builders as well as race-car manufacturers. This resulted in a vast number of small two-seater sports cars built by more-or-less competent individuals for themselves or small-scale engineering businesses and carrossiers wishing to supply sports-car starved French motorists. There were literally dozens of them, including known names such as Antem, Allemano, Callista, Marathon, Pichon-Parat, Sera, Veritas and many others.

1950-51 Callista open sports based on the Dyna X running gear, typical of many Panhard-based artesan-built cars of the 1950s. (Panhard factory archive).

Flushed with success at the 1950 Le Mans 24 hour race, Deutsch & Bonnet entered the 1951 event with two new cars, René Bonnet and Élie Bayol drove no.48 to an excellent 21st place in general classification, with Michel Arnaud and Louis Pons in no.56 managing 30th place after many problems – they were beaten by two laps by the Vernet/Pairard 747cc Renault 4CV! The Bonnet/Bayol D.B. Panhard was listed as having an 850cc engine while the Arnaud/Pons car made do with the 610cc version.

And so began over a decade of Panhard-powered successes for D.B. at Le Mans, culminating in the famous 1959 result of 9th place overall for René Cotton/Louis Cornet in a 744cc D.B. HBR4 behind two 3-liter Aston Martins, four 3-liter Ferraris, a 2-liter AC Bristol and a 1.2-liter Lotus Climax. D.B. had entered seven cars, five in the GT class and two Sport-prototypes, an astonishing number when compared to Aston Martin with five entries, Porsche and Lotus with six each and Ferrari with eleven cars participating.

Successes for D.B. only ended in 1961 when René Bonnet dissolved the D.B. partnership and threw in his lot with Renault. Panhard themselves then took over Le Mans 24-hour entries in association with Charles Deutsch and his Panhard-powered CD cars. We will look at the progress of Panhard-powered Le Mans cars in a future edition of VeloceToday.com.

Thanks to Derek Fritz for kindly permitting publication of his color photos.

The lead poster is a Press advertisement celebrating the win at Le Mans 1950 with first and second places in the Index of Performance, not General Classification as this publicity tries to suggest! “In front of 60 cars representing the world’s elite constructors….” (Panhard factory archive).

Thanks for the interesting article. I own a 1954 Monomill and one of the Formula 1 cars of 1955 converted to Formula Junior for 1959. The only one they built. It was not very successful sense it was only 850cc in a 1100cc class.

Having restored a few of the D.B.L.M the correction needs to be made that 10 of Le Mans. Competition car engines had removable cylinder heads. And only ten.

Corri el CDLM 64 numero 45 en 24 Horas Le Mans Clasica de 2004 que aparece en el articulo de Charles Deucht.