By Patricia Lee Yongue

Photos Courtesy of VintageMotorphoto unless otherwise noted.

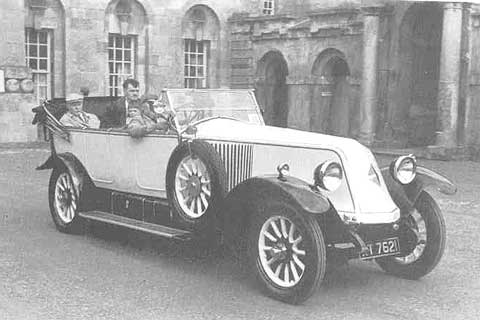

Ellery Garfield in the 1920s.

As a professor of American literature and culture specializing in the Lost Generation expatriates, I am usually on the trail of American writers in Paris. The discovery of another sort of expatriate, one who enriches my knowledge of auto racing history, delighted me. I have, however, been able to ascertain only a few details of the short, hopefully happy life of Ellerv Irving Garfield.

The remaining comprise one of auto history’s mysteries–unless you readers can assist in the solution. I would like to thank Dale LaFollette for giving me access to the Garfield letters and photos. I would also like to thank my partner in motorsports research crime, Dick Ploeg, an automotive engineer and patent attorney in the Netherlands, and Mr. Jean Barberousse of the Société d’Histoire du Groupe Renault, France, for providing information on Garfield from the Renault archives.

Despite a considerable amount of racing success in the 1900s, Louis Renault decided to keep his firm out of racing. But after World War I, with the opening of the closed circuit auto race tracks at Monza, Italy, at Sitges, Spain, and then at Linas-Montlhéry just outside Paris (1924), the honor of France, and of Renault itself, forced an end to Louis’ boycott. In fact, and here is another irony, Louis would soon order his troops to win world’s records, and he finally conceded that such records did help the sales of his passenger cars. In 1925, following a year of initiatory events, Montlhéry became a venue for breaking world records, at that time a dimension of constructors’ building and testing and of national chauvinism. Enter an American in Paris, Ellery Garfield.

Ellery Irving Garfield

Unfortunately, Ellery Garfield’s moment on the racing has been muted. He has been misidentified as “Gardfeld†and, as recently as 2006, as “J. A. Garfield.†William Boddy identifies him in his 1961 history of the Montlhéry Autodrome simply as either “Garfield†or “Garfield, the American driver.†Garfield is never credited with his full name or his considerable participation in the design and race modifications of the 1925 and 1926 records breaking Renault 40 CV (Types ML and NM, respectively).

The Big Renault 40–100 mph for 24 hours? Courtesy Renault.

Ellery Irving Garfield was born in Boston-Salem in 1893 and died in Ireland in 1930. He was, most likely, the son, grandson, or nephew of the Ellery Irving Garfield who was a stockholder in the Detroit Automobile Company, founded in 1899, then liquidated and resurrected as the Henry Ford Motor Company to support some of Henry Ford’s better ideas. That company closed shop in 1902. But there was obviously still money in the Garfield family. Ellery Garfield the Younger received a mechanical engineer’s degree at the prestigious Polytechnic School of Zurich, Switzerland, and in 1916 was hired by Renault in France, though his particular assignment has not been recorded. Inasmuch as Europe was already in the middle of World War I when Garfield arrived and Renault had diverted its attention to war related work–aircraft engine production and tank design–most likely, Garfield had some role in this service, perhaps in tank design. Fluent in both English and French, he might have assisted in the Ford-Renault tank project.

Garfield at Renault

According to Renault archival records, Garfield turned out to be an on-and-off again Renault employee. He left Renault for the first time in 1919 to return to America and work with C. Harold Wills, the “genius†engineer/designer/metallurgist who began working for Ford Motor Company in 1903 and resigned in 1919 to form his own company, Wills Sainte Claire, in Marysville, Michigan. In addition to contributing his scientific and technical expertise and creativity to the development of Ford autos and greatly assisting Ford to a successful early racing program, Wills designed the Blue Oval Ford logo. Wills’ passion for designing and engineering the perfect car was much like the passion for writing the perfect poem. It was, in fact, this creative passion that helped destroy Wills Sainte Claire, for Wills relentlessly pumped more and more money into his utopian project. (My English professor colleagues will take some pleasure in the irony that C. Harold was Childe Harold, named to his disgust–but prophetically–after the Byronic hero of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.†His mother was a Byron devotee.) At any rate, Wills and Ellery I. Garfield the Elder must have met during their earliest years of association with Henry Ford, hence setting up the connection between Wills and Garfield the Younger, who politely addressed Childe Harold as Mr. Wills.

Body work by L’Avocat and Marsuad was considerably lightened.

The Experimental Department

When Wills broke off from Ford Motor Company to establish Wills Sainte Claire, which opened officially in 1921, Garfield was somehow affiliated with the new company, although in what capacity I have not been able to determine. Due to the national financial crisis in the early 1920s and to Wills’ unbounded spending in pursuit of perfection, Wills Sainte Claire ended up in receivership by 1922. It would temporarily recover the next year, but by that time Ellery Garfield had returned to Renault and in June of 1922 was appointed head of l’atelier 41, the shop responsible for the final amendments to the chassis of the passenger (touring) car. In December of 1922, he migrated to the experimental and testing department, l’atelier 153. By 1924, as he wrote to Wills, with whom he kept up correspondence, he was starting to see what he could do with “one of the large 6-cylinder Renault chassis.â€

The tremendous post-war interest in driving and racing in Europe, and even in the United States–the knowledge that so many young men of his age were racing to la gloire–must have compelled Garfield to take the wheel of the car he had developed into a record-breaker and to stay there, as, of course, many works drivers in Europe did, although for more than closed-circuit record breaking events. By 1925, in any event, Garfield was designing, engineering, and testing the huge 9.1-liter Renault 40 CV. He became one of the principal drivers in the records breaking events at Montlhéry in 1925. Suggestive of independent income rather than a considerable salary from Louis Renault, he and his wife lived in the 16e, on #95 Boulevard Exelmans, by Metro now a quick trip to Billancourt. Feisty Gabriel Voisin, manufacturer of Renault’s local rival for world’s records, who in fact would take the 24 hours record away from Renault in 1927, lived on the same street.

24×100 Round One

In May/June of 1925, Renault took the world’s twenty-four hours record at Montlhéry, with Garfield and Robert Plessier at the wheel of the 5500 pound open-bodied car. In a June 1925 letter to C. Harold Wills, Garfield provides an account of the process of correcting the car’s bearings, oil circulation and cooling, and tire problems before driving 100 miles in one hour on the Montlhéry track. He also had the seven-seater body streamlined to a “steel sheet†four-seater.

The Renault on it’s way to a new record, but just short of the magic 24×100.

The Renault on its way to a new record, but just short of the magic 24×100.

These modifications allowed Garfield to beat the 500 km and 500 miles world’s records in three hours and six hours, respectively. He held to 100 mph on the three hour stint and 98 mph on the six hour course. He accomplished the twenty-four hours record but not as neatly as he had hoped. After twenty hours, both fan blades came off the flywheel and the camshaft drive chain broke. The damage took two hours to repair. Tire wear was likewise disappointing. The Michelins began to shed their tread after 20/25 laps (30-35 miles). He made a change to the rear axle gear ratio. Garfield completed the twenty-four hours in what he called “absolutely a standard stock car, save for the increased rear axle ratio [2:1],†at an average of 88 mph.

Great story.

Dear Patricia,

I must compliment you on this article, which is a first rate piece of original research on your part. Even though I am a Citroeniste, and in spite of the fact that Louis Renault was a real swine, I find myself drawn to the Billanacourt marque from time to time. I am looking forward to your next installment.

Sincerely,

Brandy Elitch

Dear Patricia,

Excellent reaserch and writing. Your writing reminds me aof my favorite the late Genevieve Obert. Thank you.

Tim Schlose