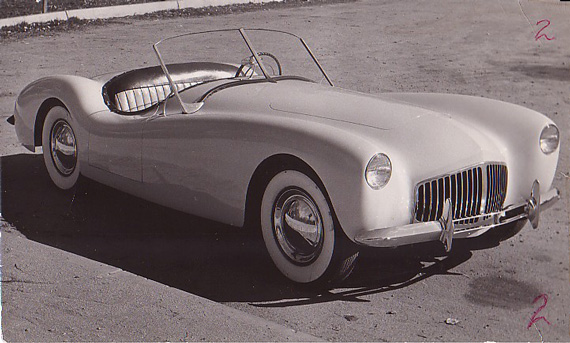

Instant Cisitalia. Americans wanted a low cost reliable sports car with European styling. What better way to go than taking a mold from the Cisitalia driven from New York to L.A. by race driver Bill Pollack and creating a new car with American running gear. This was called the Allied Swallow. Another effort, called the Vale, was inspired by the Cisitalia Nuvolari Spider (see below).

Geoff Hacker and Rick D’Louhy are dedicated enthusiasts who are breaking new ground by doing significant research on early American sports cars – those built between 1946 and 1954 – which used both fiberglass and other materials for the construction of the body (metal in the case of Paul Farago’s remarkable Fiat special)

As we’ll demonstrate in future articles, these pioneering constructors were highly influenced by Italian and French designs. To set the stage, we begin with an article taken in part from their excellent website, www.forgottenfiberglass.com, which describes the beginnings of the American postwar sports car.

By Geoff Hacker and Rick D’Louhy

All photos courtesy Geoff Hacker

In the late 40s’ and early ‘50s, if you wanted a sports car in America your options were mostly European. Making this choice meant evaluating a high purchase price, problems with parts availability, and complicated maintenance. It was during this time that a critical phase of automotive history took place – the emergence of the American sports car. These new sports cars often used designs based on European cars, if not actual copies.

American muscle, French influence. Kurtis-Omohundro Comet, from 1947, one of two designed by Indy race car builder Frank Kurtis and built by Paul Omohundro’s Comet Company. This is also been shown to be the earliest postwar sports car built and documented after the end of WWII.

Prior to 1953, there were few American sports cars available; the Crosley Hotshot (1949) the Cunningham (1951), the Kurtis (1949) and Nash-Healey (1951), but these were rare and or expensive. In a very real sense, American sports cars didn’t exist until a number of enterprising young men and small companies began to create them.

These enthusiasts often shared the following attributes:

* Pioneers of the first automotive “Start Ups” building “something out of nothing”

* American innovators advancing from novice to expertise with their resourcefulness and “can-do” attitude

* Fueled not by large corporate investment but shoe-string budgets and trial and error prototyping as small builders and independent shops.

This pivotal movement was captured in December, 1949 by author Thomas E. Stimson Jr., who penned a comprehensive article on American sports cars titled “The New Breed of Sports Cars” in Popular Mechanics. In this article he showcased the best of what was being built in America, and the reasons why they were being built. “Sports car enthusiasts who have preferred European automobiles because they could find no domestic makes that satisfy them are beginning to build cars for themselves. Scores of owners have spent from $2500 to $20,000 each to build the kind of cars they desire. One manufacturer of race cars, in answer to the demand, has tooled up for limited production of a sports car of his own design.”

The use of a reliable (usually domestic) chassis/engine a combination promised to solve the problem of expensive and often unreliable foreign mechanicals. In 1952, writer Ralph Stein wrote:

“If you’re a fairly good mechanic, you can arm yourself with some metric or Whitworth wrenches and the instruction book and do pretty well. Even if you’re a lousy mechanic, it’s worth trying because you can’t do much worse than the so-called professionals. The servicing situation is a disgrace to the foreign manufacturers who sell their cars in this country. Spare parts, except for one or two makes, are rarely available without a long wait, charges are high, and workmanship poor.”

Early American sports cars bear names that few recognize such as Glasspar, Wildfire, Victress, Meteor, Devin, LaDawri, Kellison, Byers and many others. Sometimes just one car was built, but in many cases five, ten or more examples were produced. It’s been forgotten that over 50 American sports cars were already on the road, both as one-off designs and in limited production, by the time the Corvette began appearing in showrooms in the fall of 1953. Many of these newly designed sports cars were available for purchase – and more were on the way. American sports cars were “born” in the early postwar era by motivated Americans who decided to build their own.

Not as easy as it sounds

The process of building a sports car was not for the faint of heart. Period magazines reported that building a car using an available fiberglass or aluminum body took an average of 2000 hours. That’s 50 weeks at 40 hours a week and 2 weeks off for good measure to complete a car in a full year. If you use a modern rate of $50 an hour, labor alone would top $100,000 before buying your first part.

Individuals who choose to design and build their own bodies had a more challenging course to follow. In these cases, it took an additional 1000 hours to design and build your own body. This is clearly seen by the special built by Jules Heumann (now Chairman Emeritus of the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance), on a Singer chassis in the mid 1950s where he reported that the entire enterprise took closer to 3000 hours to complete. For more on the Singer special click here.

These cars allowed enthusiasts to satisfy their desire to own an affordable American sports car. Individuals got their hands dirty and went out and built what they wanted. Handcrafted American sports cars are often seen as quintessential “Americana” showing what individuals achieved when they brought forth their creativity, design, engineering, innovation, tenacity, and hand-crafting expertise.

Influencing Detroit

An important view was offered by Walt Woron, founding editor of Motor Trend magazine. He wrote about the topic of handcrafted cars in a November, 1951 editorial titled “Amateurs are Creating New, American Designs.” Here he said:

“It has been freely admitted by top Detroit automotive designers that many innovations on production cars are the result of watching the developments of these enthusiasts who build their own custom cars, sports cars and hot rods.”

Another insight was offered by famed automotive writer Ken Purdy, in his 1952 book on sports cars titled The Kings of the Road. In this book, he dedicated his final chapter on the hope for modern sports cars – from his vantage point in early 1952. While praising young hot rodders for their clean designs, Purdy wrote “… most of the designs Detroit threatens to ram down our throats in the next few years look like something by Captain Video out of Superman. Why an automobile should look like a jet plane is hard to fathom. Jet planes do not try to look like automobiles. Jet planes, being mature and sensible things, are satisfied to look like what they are. The American automobile is still in adolescence.”

Sports car enthusiasts and hot-rodders were both being influenced by designs outside of Detroit, and in turn influencing the shape of the automobile in Detroit.

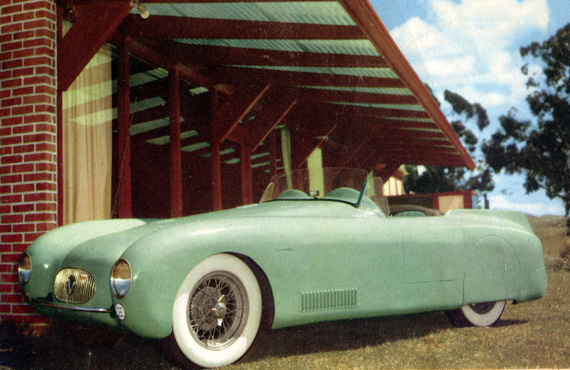

Shown here is the 1952 Vale designed by Vale Wright, an architectural designer from Berkeley, California. Design was based on the 1948 Cisitalia 202 Nuvolari Spyder. It won many awards - most notably first place in the 1953 International Sports Car Show in Oakland, California. This same design was modified by Wright and raced throughout California in a car he called “Lil Stinker.” An interesting side note - Chairman Emeritis of the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, Jules “J” Heumann, borrowed these molds from Vale Wright in the mid ‘50s, and created his own sports car based on a Singer chassis/drivetrain.

“Fiberglass” – The New Wonder Material

For an individual to build a sports car body using either steel or aluminum required a high level of skill, time, and experience. Fiberglass solved this problem and was a far easier material to master.

When fiberglass bodies were introduced at the 1951 Petersen Motorama in Los Angeles, California, they were seen as the “carbon fiber” equivalent of their day. Fiberglass bodied sports cars received immediate attention everywhere they appeared. Lightweight, strong, readily able to conform to beautiful shapes and designs, and cost effective too, fiberglass was the optimal choice for designers building race cars, sports cars, and concept cars alike. Composite materials remain the primary choice of sports and racing car bodies to this day.

The most famous and successful of the American fiberglass companies was Devin, who made a mold from the Ermini 357, S/N 1255, belonging to Jim Orr.

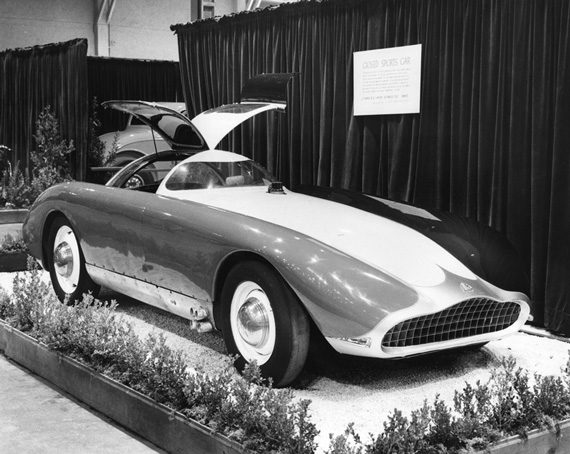

Shows, Exhibitions, and Fame

Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, handcrafted sports cars were celebrated across the land at shows as large as GM’s Motorama. They appeared in shows which including:

* The Hot Rod Exposition, Los Angeles, California. America’s first postwar custom and hot rod show – 1948 to 1949.

* National Roadster Show – also known as the Oakland Roadster Show, originally held in Oakland, California, held from 1950 to the present.

* Petersen Motorama in Los Angeles, California sponsored by Trend Inc., which published Motor Trend, Hot Rod, and other magazines. Held from 1950 to 1955.

* The World Motor Sports Show held in New York City. This was held from 1953 to 1954.

* And many others

Each of these venues showcased production cars, foreign cars, concept cars, and handcrafted cars. The stars of all of these shows were often the handcrafted cars – designed and built by talented individuals as well as small fabrication shops across America. We now refer to these shows, collectively, as “America’s Motoramas”.

Fame Beyond the Motoramas

People came to these shows to see what Americans had designed – and most of the handcrafted show cars on display could be bought or built by the public. One person’s dream could be another person’s reality. These cars were famous – they were the “rock stars” of their day, and appeared on:

* In TV

* In Movies

* In Newsreels

In fact, these cars appeared on over 100 magazine covers in this era – more than the Corvette did during this same timeframe.

Racing

While most of the first postwar sportscars were constructed for street use, at the same time there was tremendous growth in sports car racing from coast to coast. From the tiny 750cc class to the unlimited V8 classes, there were American specials throughout the grids. They were fabricated in metal, but that began to change once the potential of fiberglass was seen in sports car bodies at the November, 1951 Petersen Motorama, for it was at this show that sports cars with fiberglass bodies were first seen. The Glasspar G2, the Lancer, the Skorpion and the Wasp all made their debut.

Dick Morgensen’s first special (better known as Morgensen Special I) used a handcrafted Glasspar bodied on a modified 1950 Ford chassis – power was a 220 horsepower ’52 Cadillac mill. This car raced in December, 1952 at Torrey Pines and took first place (some sources say second). He was 31 years old when he built this car with typical construction for a handcrafted special at that time – a modified ‘50 Ford chassis (independent front suspension) with work being completed at his engine bearing company based in Phoenix, Arizona.

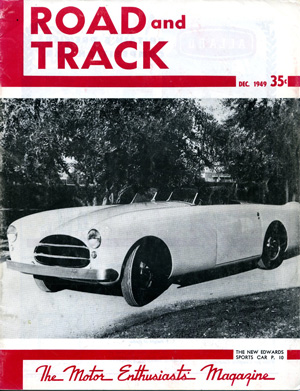

As with many early race cars in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, the Morgensen Special was a dual-purpose sports/race car. This was the same quality embodied by an earlier car built by Sterling Edwards – the R26. This car, an aluminum coachbuilt car by Diedt and Lesovsky, debuted on the cover of the December, 1949 issue of Road & Track. This car was conceived by Sterling during his postwar trips to the Continent where “Edwards decided his car must have comparable appearance, performance, and roadability” (R&T, December, 1949) of a European sports car. And what an impressive car this was!

As with many early race cars in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, the Morgensen Special was a dual-purpose sports/race car. This was the same quality embodied by an earlier car built by Sterling Edwards – the R26. This car, an aluminum coachbuilt car by Diedt and Lesovsky, debuted on the cover of the December, 1949 issue of Road & Track. This car was conceived by Sterling during his postwar trips to the Continent where “Edwards decided his car must have comparable appearance, performance, and roadability” (R&T, December, 1949) of a European sports car. And what an impressive car this was!

He won the first three times he entered races in Palm Springs, Buchanan Field, and Pebble Beach. And won “Best of Show” at the first ever Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance too – an event that he helped create in California.

_________________________________________________

More about www.forgottenfiberglass.com

For the aforementioned reasons concerning the time and effort it took to complete a sports car, more – or less – of these cars were built than one might have imagined. When looking at production numbers from the large companies of this era (Glasspar, Woodill, and Victress), each built approximately 100 bodies of their most popular design. And when you add in the smaller companies such as Meteor, Byers, Allied, Grantham Stardust, and other such manufacturers, you only get to about 1000 bodies being produced by companies, coachbuilders, and one-off fabricators from 1947 through 1956.

This estimate coincides nicely with a letter written in 1977 from John Bond, owner and editor of Road & Track magazine in the ’50s and ’60s to Ray Scroggins about these very cars – handcrafted cars. In this letter, based on his knowledge of the era, John Bond estimated that nearly a 1000 of these cars were individually and collectively built in the 1950s.

Our goal is to accurately portray the lineage, document the practices, and reveal the hidden history behind the innovators and their very first American sports cars. Through interviews, archives, and expert historians, we hope to tell the story of America’s Sports Car legacy.

Through period magazines and literature, interviews with builders and their families, and discussions with historians across America, the story of the design and building of these early American sports cars unfolds as a complex and detailed undertaking, revealing multiple twists and turns along our adventure.

The text was prepared in collaboration with our research team: Guy Dirkin, Rollie Langston, Raffi Minasian, Paul Sable, Harold Pace, Erich Schultz, and Phil Fleming. Click for more about the Emergence of the American Post War Sportscar.

It’s interesting that there is not a single word about the Crosley Hot Shot and Super Sport.

Richard, right you are, and we have included that in the post war list of available sports cars.

I did not see the Packard “Darrin” mentioned, which was quite an elegant sports car, with unique sliding doors. Nash/Healy? The Singer 4AD did have one unfortunate problem; the rear axle ratio was a real stump puller, and had a tendency to break rear axles, but it really could jump from a standing start, I owned a Singer at the time, and an HRG (another forgotten marque), which used the Singer engines. – Don