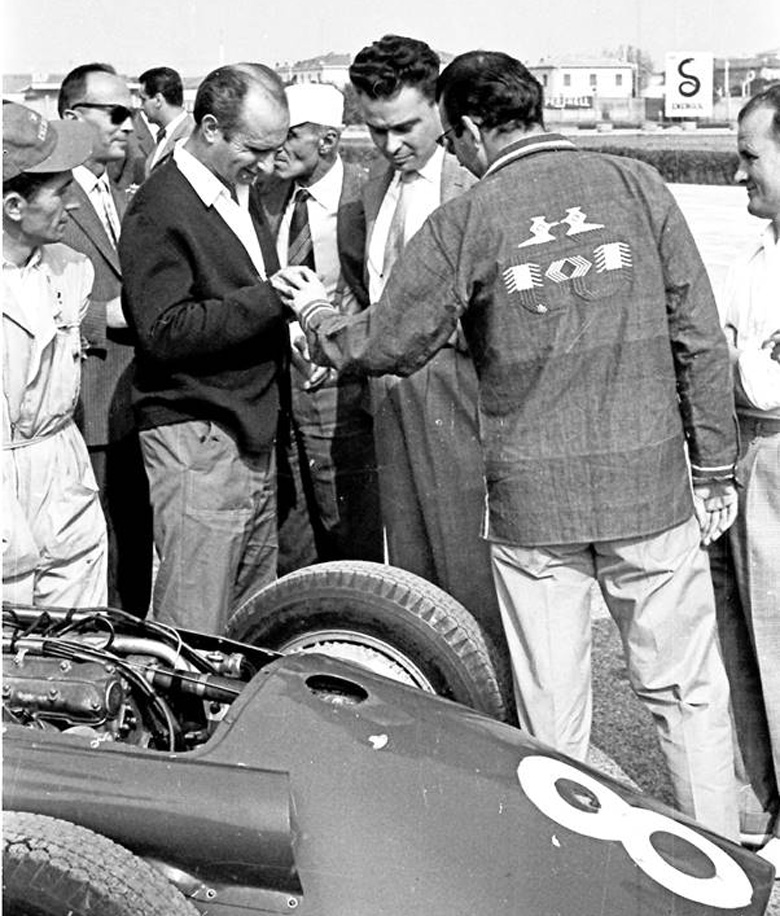

At Modena in 1957, Juan Manuel Fangio, shows Maserati chief engineer Giulio Alfieri, in jacket shirt and tie, and Swiss journalist Hans Tanner, back to camera, his bandaged wrist. Fangio would bring attention to a line of racing suits from an Argentinean-based company named Suixtil.

Story and photos by Graham Gauld unless otherwise noted

European motor racing in the years immediately following World War II tended to be a strictly European affair; that is until the arrival of the great Juan Manuel Fangio in 1948. Unlike Europe, where there was a war to contend with, young Fangio learned his motor racing craft in the wild and dangerous racing in Argentina in the 1930s and 1940s.

He proved to be not only a tough competitor but also a winner. Who better to be an ambassador for the Salomon Rudman’s Argentinean-based Suixtil company’s entry into the area of motor racing? Rudman’s enthusiasm for motor racing saw him produce clothing, which would not only be stylish but also comfortable. He took advice from his motor racing friends like Fangio as to design and functionality.

Thus was launched the Suixtil range: the first range of clothing specifically designed for race drivers. Salomon chose a number of the leading Argentinean drivers to be his ambassadors.

Juan Manuel Fangio was the first to carry the script of Suixtil on his racing clothes and had been particularly successful with his much modified 1939 Chevrolet.

When Fangio and countryman Benedicto Campos arrived for their first major season in Europe in 1949 they were fully kitted out in light blue racing pants and white shirts or yellow short-sleeve polos sporting the Suixtil logo. They had entered a new world in the old world.

Today there are many millions of Formula 1 enthusiasts glued to television sets all over the world thrilled by the speed, the electronics and the handling of modern Formula 1 cars. But for a moment, let’s have a closer look at racing in Fangio’s day by selecting one typical non-Championship Grand Prix race, the 1957 Grand Prix of Modena.

Since Modena was the manufacturing center for both Ferrari and Maserati, the race always had a good entry. As young motoring journalist, I traveled all the way from Scotland to Italy for the race.

The Autodromo di Modena started out as a small airfield on the outskirts of town forming an almost square format with a diagonal runway running north to south. The surface was of concrete and in 1957 it was breaking up with fissures across the start and finish line. There was a simple open grandstand and a row of small messy pit boxes, all made out of slabs of concrete. There were no toilets, no restaurant and only the occasional van selling sandwiches. This facility was not the place to find a lush hospitality unit and luxuriate with a gin and tonic. If you wanted a beer, you brought it with you.

Enzo Ferrari’s old friend and chief mechanic Luigi Bazzi steers the brand new Ferrari Dino Grand Prix car as it is pushed through the unsurfaced paddock behind the pits.

At that time the entire grid, apart from around six cars, was made up of private entrants, some of whom were living on a shoestring and going from race to race with a race car on a trailer. Two of the private entrants, Horace Gould and Bruce Halford, had brought their Maseratis over from England for the season and were living in a cheap room in a local hotel. As Bruce Halford told me at the time, “We lived on a pint of milk and a plate of pasta every day waiting to hear from the next organizer willing to offer us starting money.”

Famed English racing journalist the bearded Denis Jenkinson with privateer Bruce Halford in the pits. Note the slapdash way the drivers name cards have been printed.

In those days racing was not organized in the business-like way it is today. It was the race promoter and his local traders who would not only find the money to set up the race but would then offer drivers $50 to $100 to enter their cars. In turn, the drivers hoped to win some prize money, which usually was spread over the entire field so that everyone got something.

At Modena that year there were roughly six race drivers who were fully paid up members of factory teams; two from Maserati, two from Ferrari and two factory BRM Formula 1 cars. These were the drivers who had separate private contracts, usually with a petrol company, a spark plug company and possibly a manufacturer of brake materials. These drivers were paid a commission depending on their race results, which were used for advertising displays.

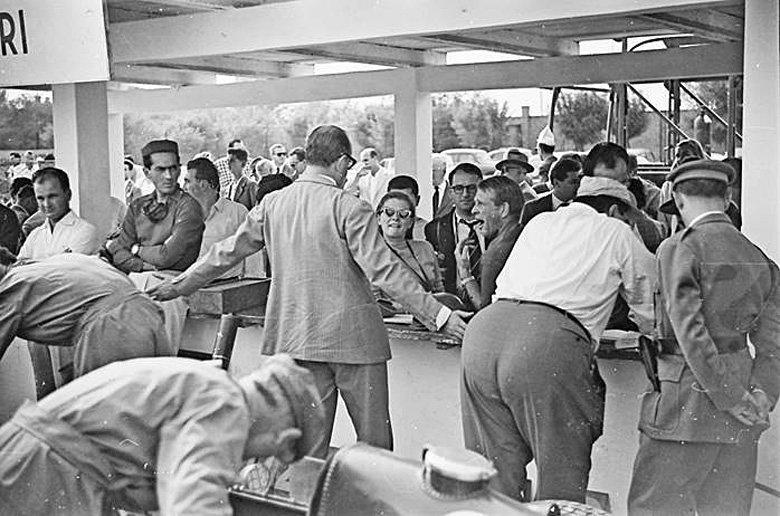

Ferrari team manager Federico Amorotti, dressed formally in a suit, gives instructions to driver Peter Collins whilst Ferrari’s other driver, Luigi Musso (in the beanie hat) tries to hear what he is saying. Note how close the spectators were to the drivers back then with no barriers or officials.

There was little or no live motor sport on television as television itself was struggling to get a foothold. Lack of modern day technology meant that a race was captured with a hand-held camera using film which took time to be developed and edited. Therefore, newspaper and magazine advertising were much more important.

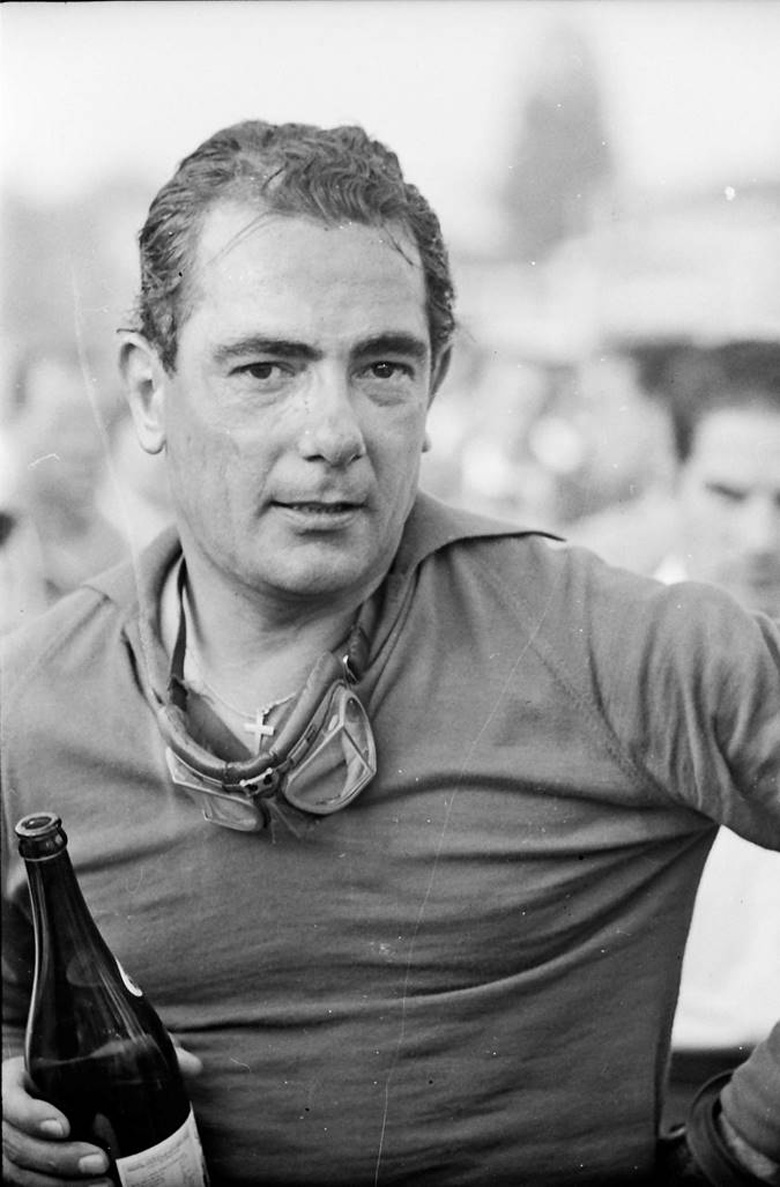

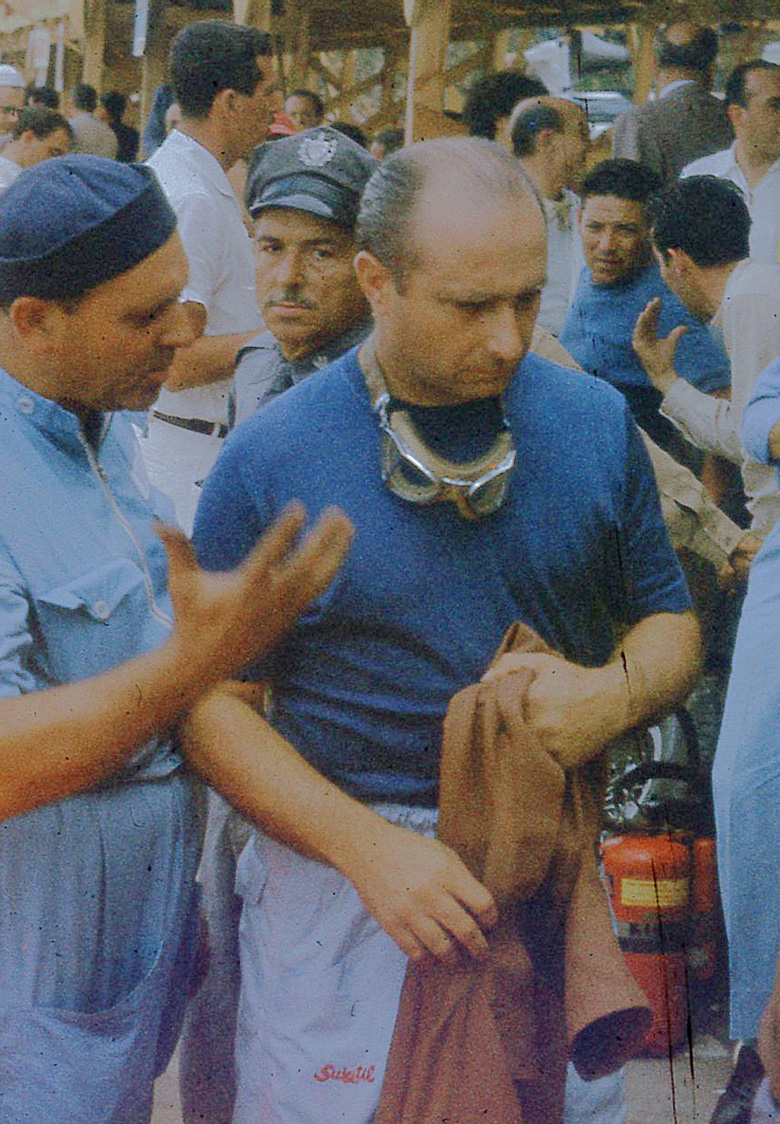

There were one or two Suixtil supported drivers in that Modena race. The small and wiry Frenchman Jean Behra, who had a penchant for wearing crimson sports shirts; the ebullient French-American Harry Schell, who arrived at the race with sticking plaster on his face following an accident on the Tour de France the previous weekend, and the great Juan Manuel Fangio, the man who brought Suixil into European Grand Prix racing.

For Fangio, however, it was a case of standing on the sidelines. On his way to Modena, while driving his Lancia Aurelia B20, a lorry driver pulled over without seeing Fangio coming up behind him. Fangio deftly spun his car but hit the truck and sustained a fractured wrist. It was typical of the enthusiasm for racing at the time that the lorry driver, realizing that it was the great Fangio he had caused to crash, broke down in tears and was comforted by his hero. Fangio was due to drive a powerful 12-cylinder Maserati in the race, but it was decided to give it to the flamboyant Harry Schell. However, Schell could not get used to the car so he stayed with one of the six-cylinder cars.

After practice, all the drivers went to a local hotel and stood around in the bar amongst the enthusiasts and enjoyed themselves. It was a relaxed atmosphere which would be totally impossible to envisage today with television-inspired mass enthusiasm. Fans were polite and respectful and in return the drivers were open and friendly.

French driver and race winner Jean Behra immediately after the race, no fireproof coveralls, just his Suixtil polo shirt and cotton pants.

In a word, motor racing had a certain magical style sixty years ago, a style which aptly suited the Suixtil low-key high-fashion brand. Suixtil was also a promotional exercise which inspired many other companies to follow. The familiar race suits, which were later given to drivers by the Dunlop tire company, were similar.

This is a enlargement of a photo taken of Fangio at the Cuban Grand Prix in 1957 by Robert Pauley. The Suixtil name can be seen on the slacks.

Only a few years after that Modena race the Argentinean founder Salomon Rudman and the Suixtil company ceased production. However, today we live in a stylish society and the company has been reborn in Hong Kong by Vincent Metais, featuring overalls and sweaters made in the identical designs and styles of the 1950s. Juan Manuel Fangio started the trend sixty years ago and now it has returned to the scene.

Their web site www.suixtil.com contains a number of fascinating photos of drivers and racing back then.

Yet another fascinating story by master raconteur Graham Gauld. Thanks Graham and keep sharing your experiences of those times with us.

Like my friend Graham, I was young and fortunate to be on hand

for this event, and the memories are vivid to this day

Items that stand out would be testing of the new Dino Ferrari, and having a free drink thanks to Raymond Mays of BRM..

His team had made the long journey from Bourne, and told me how keen they

were to sign up both Behra and ‘arrie Schell for next year–and they did !

Another prospect was new boy Bonnier who i knew from working for a Swedish

motor magazine then and he did test their car also.

Regarding Fangio and his accident, American Gary Laughlin hitched a ride

with the world champion from Milan and wrote of his mis-adventure for

AUTOSPORT magazine at the time

Final bit of drama for myself was invite to Ferrari works, driven by Tavoni

in their 1100 FIAT, Kind man but not a good driver and up front Phil Hill

was giving him a bad time of wanting to be on Grand Prix team for 1958,

Tavoni was avoiding bicyclist and telling my friend Phil to be patient, his

turn would come. I could barely keep from laughing aloud !

Just a minor event, but so important in my world of racing and glad to

have my ” fotografio” pass for the pits and on the track.. Thanks for the Gold

Graham.

Jim sitz

I clearly remember the Argentinian Maserati trio Fangio, Gonzalez and Marimon wearing those blue and yellow sports shirts in the 1953 British Grand Prix.

These old photos are superb to study. That’s an interesting photo of Luigi Musso watching Peter Collins. There was no love lost between them because of the agreement Collins and Hawthorn had of splitting all their prize money but leaving Musso out. It seems to capture the atmosphere between them. Musso is also wearing an enormous watch for the 1950’s. The only huge watches I can think of back then were the WW2 German pilot watches.

Wonderful to come upon this vivid snapshot and, remarkably, recollections from people who were actually there, of European racing in the glorious fifties and early sixties, which to many of us Down Under who were introduced to motor sport at that time and avidly followed, though sadly usually from afar, the exploits of Fangio, Hill, Bonnier, Schell, Behra, Collins et al, will remain its golden age.

We must be grateful for the devotion of well-heeled enthusiast owners that ensures many examples of the machines from that era are still being raced.

hey say that if you live in the past you have no future. BUT those were the great days of motorsport. Fabulous story.