By Dr. Patricia Lee Yongue

B&W photos from the book and our thanks to the author.

Picture this: Retromobile, Paris. Outside the day is wintry; inside you are sweaty. You are scrunched in a swarm of manic but happy buyers at a memorabilia stand. You are barely able to move, let alone comfortably sift through the thousands of photos, post cards, and documents that are scrunched together on a low table barely able to contain them. You strain your eyes and arms searching for your “find”-after awhile, any find.

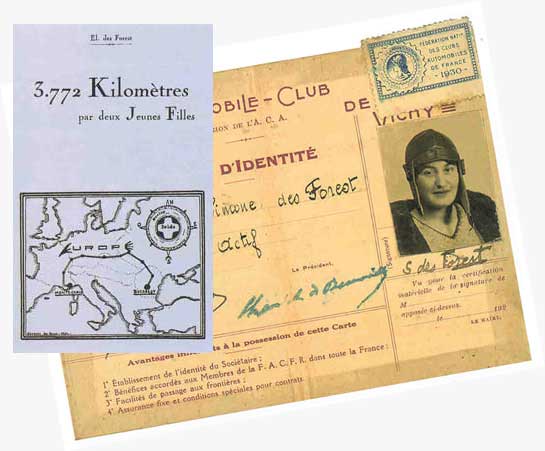

Voilà! Serendipity is on your side today. Among the “yellowing papers” in an old shoebox you manage to clasp lay your treasure: the notebook Simone des Forest kept of the 1934 Rallye Monte Carlo. Mlle. des Forest and her co-pilot Fernande Hustinx drove their Peugeot 301 from Bucharest to Monaco, nearly 2400 often snow-laden miles, and won le coupe des dames. To your delight, des Forest enhanced the technical entries of the arduous journey with vivid descriptions, photos, and charming little drawings.

Some seventy years after the 1934 Monte Carlo rally, when he discovered Simone des Forest’s forgotten logbook, master collector and historics competition driver Jean-François Bouzanquet knew precisely what to do. “Pour la petite histoire, c’est grâce à Simone des Forest que ce livre a vu le jour.” Largely out of his own substantial collection of photographs and documents and the older and newer accounts of other writers he composed his own narrative of the history of women in motorsports. It is largely a photographic history, but the images individually and collectively are remarkable. To date, it offers the most complete account of women in motorsports, and the most complete historical assemblage of photographic images, through the 1960s.

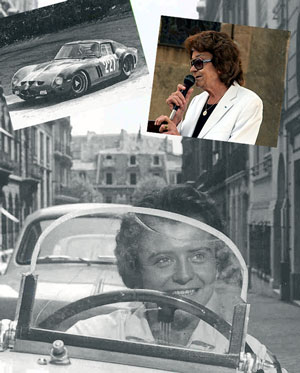

Annie Soisbault, who provides a brief preface for the book, began driving her TR3 in 1958 and was soon racing a GTO Ferrari at Mont Ventoux. The Marquise de Montaigu retired ten years later and made a guest appearance at the recent Hellé Nice Memorial ceremony in Sainte Mesme, France (see VT),where she was photographed by Mary Ann Dickinson (see inset).

Although readers familiar with individual women racers-Elisabeth Junek, Hellé Nice, Pat Moss, and Michelle Mouton, for example-may not find new information about them in Bouzanquet’s text, they will more than likely learn a good deal about others and find helpful bibliographic references. All readers, however, should appreciate the distinctive gathering of truly distinctive women and the organizing of women’s racing history into both cultural moments and corresponding genres of racing. There are some notable American women represented, principally those driving during the 1950s and 1960s (Betty Skelton, Denise McCluggage), after the prohibitive American Auto Association Contest Board lost its control of motorsports once and for all; but the majority of racers who make their appearance in ‘Femmes Pilotes’ are European and British.

Road and rally racing, speed trials, hillclimbs, and all-women track racing such as that held at Montlhéry and Brooklands are thus the primary forms of racing covered.

The proto-moment for racing women occurred, of course, in 1888, when Bertha Benz snuck out of her house early one morning, two sons in tow, purloined the three wheeled, single cylinder motorwagen designed and patented by her husband Karl, and drove the vehicle as fast as she could to get from Mannheim to her mother’s home in Pforzheim, Germany, before dark.

LeMans, 1951. The team of Miss Betty Haig and Mme Yvonne Simon do some fine tuning to their 2 liter Ferrari 166MM. The crew finished 15th overall, ahead of the 2.5 liter Type 212 Export Ferrari of Moran and Cornacchia.

As wife and business partner who also possessed technical acumen, she determined to test the car’s reliability and endurance in order to convince unconvinced Karl to market his invention before someone else did.

In effect, Frau Benz became the first driver to make a long distance run in a motor car and by default the first female to “race” a car.

After the era of Frau Benz and the Duchess d’Uzès, owner of a Delahaye, who proudly incurred the first speeding ticket, the decades of the twentieth century proceed luxuriously, beginning with adventurous Camille du Gast, who drove a 20CV Panhard Levassor to a 30th place finish (out of 154 entrants) in the 1901 Paris-Berlin race and a Dietrich 35CV in the catastrophic 1903 Paris-Madrid race. The introductory texts to all the chapters/decades quite nicely foreground the actual racing history and accounts of certain specific races with the cultural environment. Needless to say, the 1920s and early-to-mid 1930s shine; yet, the 1950s and 1960s offer superb representation. The photographic images increasingly astonish with their sheer numbers, diversity, and clarity. While most “histories” of women in racing unintentionally give the impression that racing was an occasional indulgence for women, which it was and/or had to be for some, ‘Femmes Pilotes’ leaves no doubt about women’s sustained serious participation in motorsports to the extent that patriarchal law allowed.

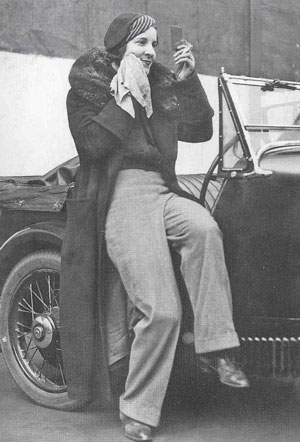

One aspect of the book that some readers might question is its relative attention to traditionally feminine concerns: fashion, hairstyle, glamour poses, etc. After all, the argument goes, motorsports history, i.e., male auto racing history, does not feature such concerns. Men are not pictured sitting on their cars, legs arranged cutely or provocatively, or fixing their hair, or entering prison, like British driver Fay Taylour, all smiles and dressed for afternoon tea.

At least two conditions prevail. First, available historical photographs and newspaper accounts emphasize the traditional feminine appeal (or not, as in the case of Nazi collaborator Violette Morris) of their female subjects. Second, the socio-cultural and often political history of women in motorsports entails the interplay of conventional femininity and an unconventional female pursuit, however prescribed both the femininity and unconventionality may be and for whatever reasons. Not too much has changed in terms of advertising and media coverage, not in the United States, at any rate. Today, for example, Danica Patrick, an experienced driver, clearly does not—or cannot–express too much resistance to being portrayed as a sex siren, and not coincidentally she remains the country’s most visible, perhaps most highly compensated, female auto racer.

To his credit, Bouzanquet does not exploit the “girlie” mode. The photos and accounts of the women as racers far exceed those featuring beauty poses. He also interweaves into his straightforward history narrative descriptions of a number of important races as well as identifying countless less known and diverse events that verify women’s uninterrupted interest in motorsports. Bouzanquet, in other words, demonstrates a high regard for “toutes les femmes” to whom he dedicates this book.

By appearance, ‘Femmes Pilotes’ seems to be a coffee table book. Too many auto books are in fact merely coffee table books. They have given those who do not yet take auto history seriously the impression that auto history is a coffee table subject. Like other auto books whose size and sheen enhance the necessary visuals, ‘Femmes Pilotes,’ should not be mistaken for a pretty “picture book.” The assembly of photographic images on the book’s glossy pages is effective.

1958, Monte Carlo Rallye. Driving a Giulietta Sprint, Madeleine Blanchard and Mrs. Wagner won the Ladies Cup.

The text is well-researched, as the considerable acknowledgments and substantial bibliography indicate. Unlike some women’s motorsports historians whose treatment of the early female racers repeat errors made in S.C.H. Davis’s otherwise historic ‘Atalanta,’ Bouzanquet has consulted sources with more current and accurate information, although both the editor and this reviewer found several minor factual errors in the book. The index is perhaps the book’s weakest component, as it lists only the women drivers alphabetically (and their major races and dates following their names) but does not inventory the races separately or inventory other material researchers would find helpful.

‘Femmes Pilotes de Courses Auto 1888-1970,’ by Jean-François Bouzanquet, ETAI, 2007. 176 pp. Illus. EUR 42.71. Bibliography. Index.

Trans. ‘Fast Ladies: Female Racing Drivers 1888-1870,’ Veloce Publishing, 2009. 176 pp. Illus. $59.95 USA Order Here

A fine companion to this history, covering contemporary racing through 2000 is Susan TP-Jamieson’s and Peter Tuthill’s ‘Women in Motorsport from 1945 (Jaker/BWRDC, 2003).

Thanks Pat for a fabulous article. I find these early women racing pioneers all the more remarkable because racing during those decades was such a rich sport, not one a woman could easily enter because she was perceived as having “racing talent.” Yet these women raced expensive exotic cars and set racing records.

Mary Ann Dickinson

I LOVE it! I grew up in a large family, 8 boys and 2 girls, I was the oldest. The 2 girls were “tomboys” and very athletic and competitive, the oldest was the fastest sprinter in school by far and won many races aginst boys. Of course they can do it!

I am thrilled to see that a woman raced a Ferrari 250GTO. WHY has this been kept secret from us?

Great article. Cudo’s to Dr. Yongue for writing a very informative article. Good point about Frau Benz being the first long distance driver, racing the sun.

She convinced her husband to put better gearing in the three wheeler for better hill climbing.

Someone needs to write about North American women racecar drivers.

Great book that took great courage to translate from the French. Not the forum, perhaps, but if this book interests you take a look at The American Motorcycle Girls 1900 to 1950 by Cristine Sommer Simmons published in mid-2009.

Dear reader(s).

In my automobiliashop “le petit salon de l’auto”in holland I got hold of a silver cup

with the following inscription “Rallye Feminin automobile 24 mai 1959

coupe de la reserve d’albert plage” Can somebody help me to trace the history of this cup? If you look at http://www.lepetitsalondelauto.com you can see a photo of the cub.

Meico Koudstaal, hiolland

I remember Betty Haig with great affection. My father, Dick Bostock, bought his AC Ace Bristol from her in about 1970/1. I was a schoolboy at the time and his (rather late) arrival in it for Old Boys Day at school was one of my proudest moments as he was something of a renegade and the school drive was long and straight!

She had a soft spot for my father, he was the competitions secretary of the HSCC (which she of course founded) and already campaigned a blue Aceca quite well and she refused to sell it to anyone else. She wanted to consolidate her collection to BMW’s and sold him the Ace for £1500 – it was probably one of the best in the country.

She indulged me as a 13 year old boy when we went to see her collection and house once, and I thought she was a wonderful heroine.