Review by Michael T. Lynch

The Untold Story of the Illegitimate Children of Ferrari and Chevrolet

In these days of eight figure auctions prices, Ferraris are held in the highest esteem in collector circles. Some acolytes act is if these cars were gifts from heaven, rather than coming from an industrial area in Italy with a bad climate and smog caused by tile factories. I forgive all that because of Reggiano Parmigiano.

The worshipers might feel differently if they knew it was not always so. Some of the great Ferraris in the history of the marque were relegated to barns, chicken coops and abandoned to the elements for years before being restored to the specification they now present at the great concours and vintage races of the world. Any kind of variance from “original” is considered a sacrilege. The idea of a non-Ferrari part on a significant car almost makes some faint. However, race cars were changed, sometimes from race to race to be made more competitive, so who is to say what is original.

S/N 0046 was a Touring bodied barchetta modified by Zagato and later equipped with a Chevy V8. Photo credit Darrell Westfaul, from the book.

The fact of the matter is that when early Ferraris arrived in America they were successful for a time in racing. Nothing is older than last year’s race car, so they changed owners and dropped down the results sheets as years passed. The next part of the cycle began when the Ferrari engines gave up. Now, the owner was in real trouble, because the cost of an engine rebuild was much more than the car was worth. Even at that late date, the Ferrari chassis was still often superior to some of its competition. Developments in the U.S. auto industry would affect what happened next.

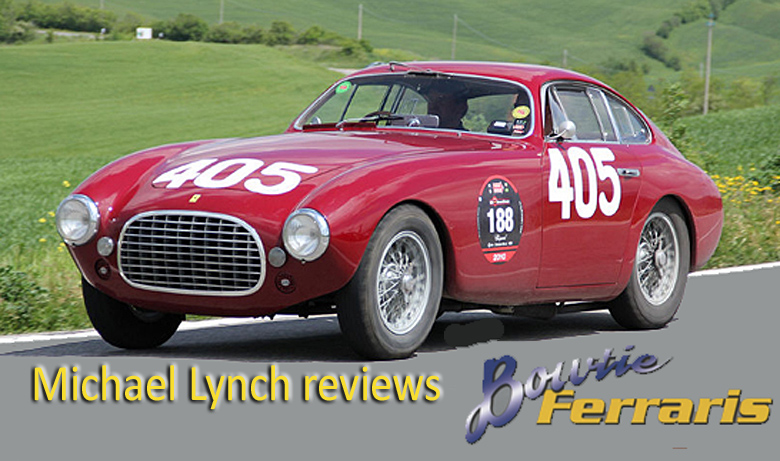

Most of the superb color images for the Bowtie Ferrari book are courtesy of Hugues Vanhoolandt, such as this view of 1951 Mille Miglia winner S/N 0082 on a recent Mille Miglia.

Ed Cole became Chief Engineer at Chevrolet in 1952. He had worked on Cadillac’s overhead valve V-8, introduced in 1949, an engine that found success in early sports car racing, mostly in Allards. At Chevrolet he designed a light, compact, short-stroke, overhead valve V-8, introduced in 1955, that almost immediately became the darling of hot rodders. It replaced their beloved Ford flatheads which had to have expensive speed equipment to equal the Chevy’s power and the newer V-8 also weighed 70 pounds less.

As the speed equipment industry added parts for the Chevrolet, its reliability in racing increased and they were often used in American road racing specials. Descendants of the small block Chevy V-8 remain in production today and it could be said that the engine has won more races across more disciplines that any engine in history. Cole’s later elevation to Head of the Chevrolet Division and ultimately, President of General Motors was not undeserved.

There are many period photos of the Chevy engined Ferraris. Here is S/N 0406 with a 310 inch Chevy V-8 as campaigned by Hal Rudow in 1962. Courtesy Martin Rudow, from the book.

Obviously, because of cost, reliability and availability, the Chevrolet V-8 began making its way into both racing and street Ferraris not long after its introduction. Some of the race cars continued to win despite their age.

Randy Cook has written a fascinating, well-researched book on this phenomenon – Bowtie Ferraris, Chevy-engined Ferraris from the 1950s and 60s. He takes us car-by-car in serial number order through 71 Chevrolet transplants into Ferrari cars produced from the beginning of the firm until the end of 1960.

But photos of Chevy engines as installed in the Ferraris are harder to find. Here is Oscar Kovaleski working on the fuel injected Chevy engine installed in his famous ‘Car 54 Where are You’, S/N 0588. Photo from the book.

There is little doubt that the formation of the Ferrari Club of America in 1962 and the writing of the classic Warren Fitzgerald/Richard Merritt book, Ferrari The Sports and Gran Turismo Cars were inspired by what the purist Ferrari community viewed as desecration of important automotive artifacts. Some of the founders had seen a 166 Vignale Coupe 0024 (originally a Barchetta, then a coupe and now carrying a reproduction Barchetta body) at Elkhart Lake that year and it had been fitted with a Chevy. They were not impressed. Soon, another step in the process on the road from barns to the lawn at Pebble Beach began.

Even Testa Rossas received Chevy engines. Here is Gordon Glyer at Sacramento in 1961 with S/N 0718. When he sold it without the engine to Jack Wilke, a Chev was put in its place. Courtesy Web Canepa from the book.

Fitzgerald and Merritt taught us the basics of Ferrari’s numbering system and by the early 1970s, matching engine and chassis numbers had become the Holy Grail. Knowledgeable enthusiasts began to realize that to attain their highest value as collectibles; Ferraris would have to be reunited with their original engines. This set off a search by a knowledgeable few. Some had the money to buy engineless cars and look for the engines later. More impecunious cognoscenti concentrated on finding the engines, hoping for higher bids later from the car owners. I wrote about the latter part of the odyssey in a slightly fictionalized piece in Cavallino 23 (Aug/Sept 1988). It has certainly paid off for some. A recent transaction traded a four cylinder Ferrari engine intended for its original chassis in exchange for a complete restoration of a mid-50s Ferrari race car.

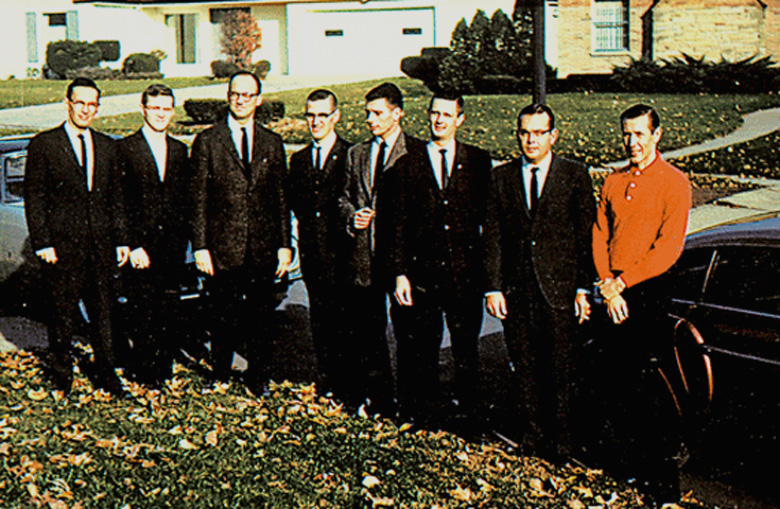

The founding of the Ferrari Club of America, November 19, 1962. From left, John Delamater, Ralph Smith, Gerry Buhrman, Dick Merritt, John Lundin, Ken Hutchison, John Habach, Larry Nicklin.

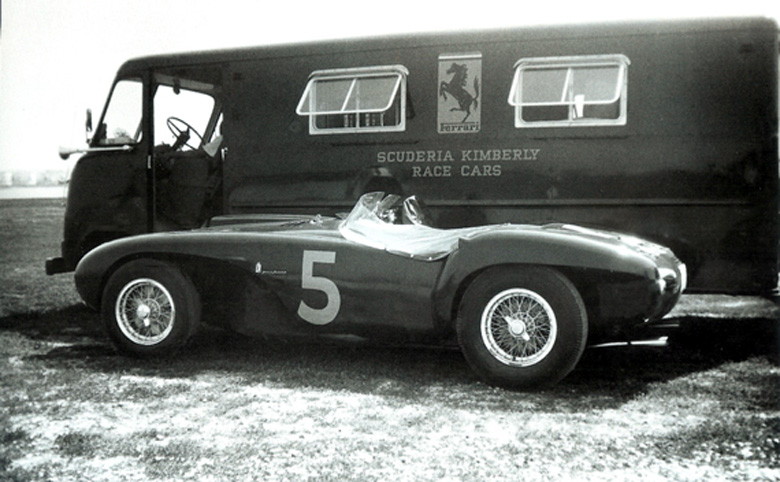

Randy’s book makes for both a wonderful read and an important reference. When the information is all in one place it becomes immediately apparent how many highly significant Ferraris did get a Chevrolet transplant. They include two Mille Miglia winners (1951 and 1953), the first place Ferrari from the 1954 Carrera Panamericana and Jim Kimberly’s cut-fendered Ferrari 375 MM that totally dominated the 1954 SCCA racing season. Iconic models such as the 166 MM, 750 Monza, 500 TRC and 250 Testa Rossa all received Chevrolet engines.

Jim Kimberly’s car at Fairfax Airport, Kansas City KS, in 1954 when it dominated SCCA C Modified. The car was painted the same red as the factory paint job on the truck. Credit Michael T. Lynch

One cannot write a review without some petty criticism. The only thing I can find fault with is the several names that are misspelled (Wayne Thomas was actually Wayne Thoms, etc.) and the incorrect designations of a few people’s positions in their descriptions (Warren Olson was not the chief mechanic in Lance Reventlow’s Scarab operation, but the General Manager). At least two captions are mislabeled. One identifies Richard Lyeth’s mechanic as Lyeth himself. In the section on 250 TR 0728, the 1958 Le Mans winner, there is a picture from a period Fuller Brush Catalog taken in front of the factory. It shows a Ferrari sports racer being looked at by Phil Hill and Gaetano Florini, later to become head of the Assistenza Clienti in Modena. The caption identifies it as 0728, but it is actually 0726 before it was converted to a 1959-style body. It is painted with Hill’s winning number from Le Mans earlier that year for this posed shot.

Indexes are fading from the publishing world, but considering some will be using the book as a reference, one would have been preferable. Jody Ellis did a fine job of layout and there is a bibliography. I was not impressed with the front cover artwork, but the back cover shows three cars from the book, including Randy Cook’s. They tell us what the book is about.

Historians often know more about a car than the owner, but Cook’s book, shows that Packard’s 1901 slogan, “Ask the Man Who Owns One” is often the best source of information. Randy has owned a Chevrolet-powered Ferrari Pinin Farina Coupe for many years. He has now written a book on his car’s brethren that does a great service for the Ferrari community and beyond.