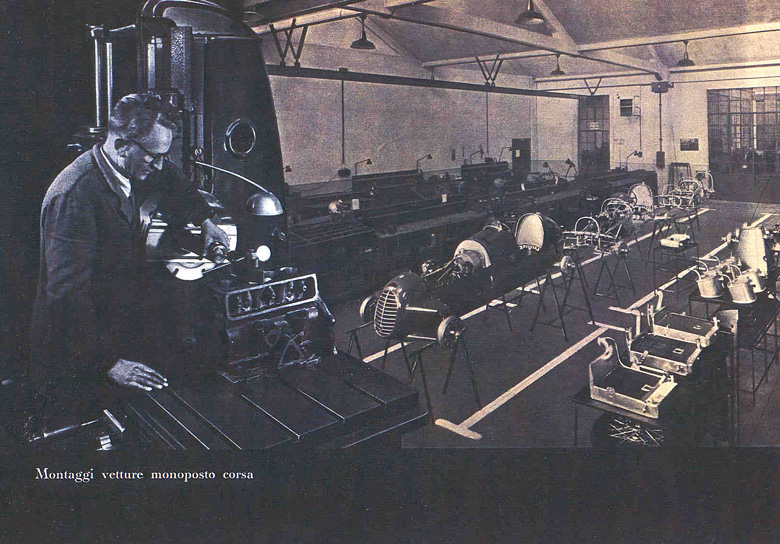

Cisitalia is the acronym of “Compagnia Industriale Sportiva Italia”, the official name of the conglomerate of Piero Dusio’s business ventures. The logo, a stylistic Alpine goat (Capra ibex), was also an idea of Dusio, because these animals are reputed for their courage, speed and agility. The colors he chose – blue and gold – are those of the city of Turin. At right, the first batch of the Cisitalia D46 racing cars.

Story by Gijsbert-Paul Berk

The name Cisitalia is inseparably linked to that of Piero Dusio. This Turinese sportsman, racing driver and entrepreneur was president of Juventus, Turin´s successful football (soccer) club and founder of the Scuderia Torino. His business enterprises were registered as Consorzio Industriale Sportivo Italia. Indeed: CISItalia! The business conglomerate included textile mills, a trading house, a bank, many hotels, sportswear manufacturing and bicycles.

The Fiat 1100, Dante Giacosa and Piero Dusio combine to create a work of art

In the summer of 1944, Rome had been liberated but Turin was still occupied by the German army. Dusio and some friends discussed the prospects of Italy resuming a role in motorsports after the war. Dusio proposed to build a series of small, light single-seaters, all with the same power, which would allow drivers to participate with machines on various circuits to match their driving abilities.

Dusio’s dream was in fact to create a new, financially attainable racing class which would enable promising pilots to prove their talent and gain experience. A quarter century later, the same concept would be adopted by world-class manufacturers such as Ford, Renault and Volkswagen, with their one-make championships.

But how did Dusio manage to make his ambitious plan come true in war-torn Turin? Simple! He persuaded Dante Giacosa to help him.

Producing 20 brand new race cars in Italy in 1946 was surely an accomplishment give the times. This is from the Cisitalia brochure.

When Dusio approached Giacosa, life in Turin was grim; The Allies were bombing targets in and around the city on almost a nightly basis. For Giacosa, this was not a very happy time either. He had been forced to move to a room in a hostel for Fiat employees, because his own apartment had destroyed in an air raid. Due to bomb damage, Fiat’s engineering department at the Mirafiori plant had been relocated to a building of the Duca degli Abbuzzi School; unfortunately, they had no interesting projects to work on.

Giacosa creates the Cisitalia in his spare time

In his autobiography, Dante Giacosa admits that while the idea of building a racing car strongly appealed to him, he had misgivings regarding the feasibility . However, he accepted Dusio’s invitation to meet him at his villa.

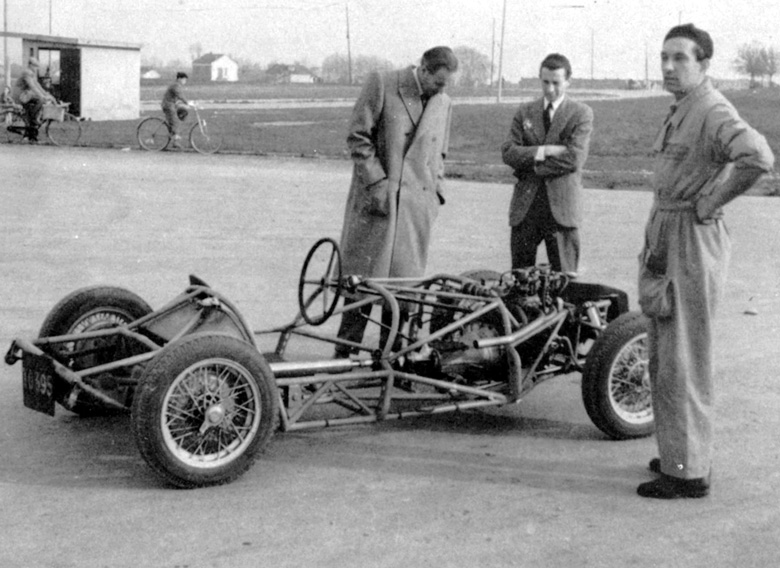

Dante Giacosa, with raincoat, behind the prototype of the Cisitalia monoposto during one of the test runs.

After Dusio outlined his ideas, Giacosa told him that they should rule out building a racing car from scratch. However, by using components of the Fiat 500 and 1100, he would be able to construct a machine with sufficient performance to compete against the small single-seaters used in the United States for dirt-track racing. they discussed the work that would be involved in designing, building, testing, creation of a prototype. Finally, they considered the limited production of such a racer. Giacosa pointed out that he would need the permission of his superiors at Fiat. but he was sure that he would get it since Fiat management had not assigned him any definite duties and he had time on his hands. He would, however, need assistance from professional draftsmen, welders and mechanics.

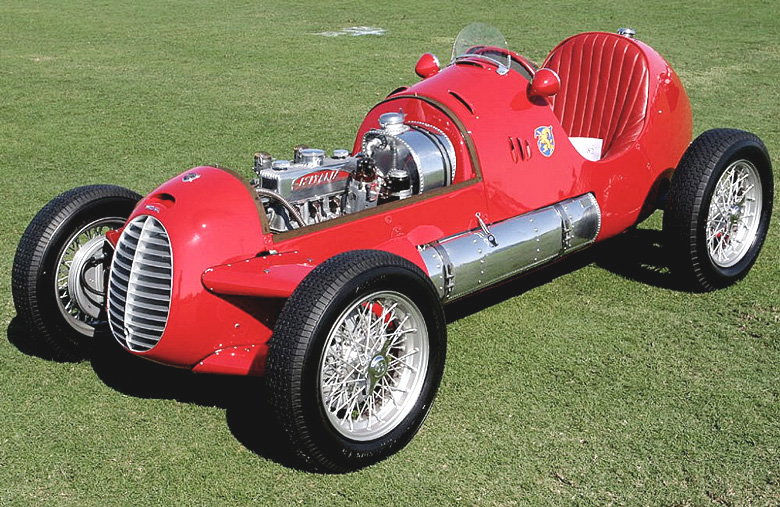

A Cisitatia D46 in all its glory. These small monopostos were successful contestants in Italy’s postwar races, even feared by competitors who drove prewar cars with twice the cylinder capacity.

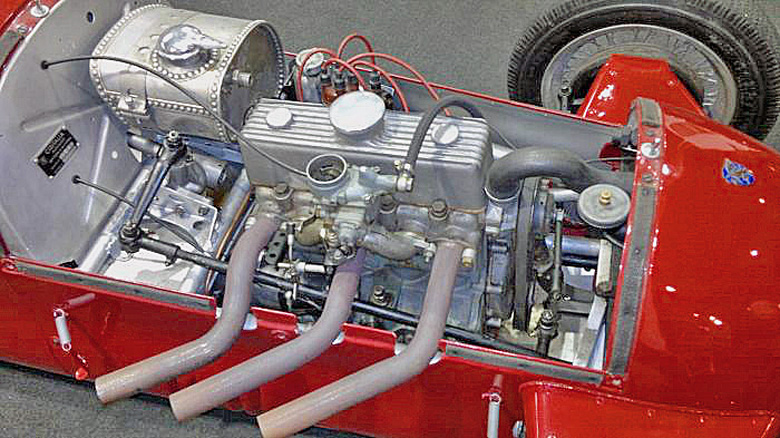

As this photo shows, the Fiat 1100 engine which powered the first Cisitalia D 46 had only a single downdraft carburetor. Later this was replaced by and two Weber 36 DR 4 SP carburetors. This brought the peak power to 70 HP @ 5800 rpm.

Dusio agreed and offered him the use of his villa at the Corso Galileo Ferraris. The Dusio family had moved out of Turin but a caretaker and a servant still lived downstairs. “Compared with the hostel where he had found shelter, Dusio’s villa was a palace,” wrote Giacosa in his memoirs. “On the top floor there was a bedroom, a magnificent bathroom and two other rooms to set up drawing boards.” In addition, he could also use Dusio’s machine shop at the Corso Peschiera..

A space frame from bicycle tubes

While Dusio was showing him around, Giacosa became interested in the workshop where the frames for the Beltrame bicycles were made. There was a stock of chromium-molybdenum tubes of various diameters, which Giacosa realized could be used to build a racing-car frame which would combine low weight and great strength. Due to his recent work on an aviation engine for Fiat’s aeronautics division, he was quite familiar with the construction of aircraft fuselages made from small diameter tubes.

One of the first Cisitalia coupés, the C202 Cassone. In Italian a ‘cassone’ is an elaborately decorated piece of furniture or a jewelry box. The chassis and body were developed by Giacosa before Savonuzzi took over.

After receiving a letter from Dusio confirming his appointment as project manager for the racing car and retaining his services as consultant to Cisitalia until the end of 1945, Giacosa installed himself in Dusio’s villa. For months, he worked every evening, including weekends, making sketches, drawings and calculations. Although Edoardo Grosso, an excellent draftsman, regularly assisted him, most of the time he was alone. In his memoirs, Giacosa recalled the words of Leonardo da Vinci: “If you are alone you will belong entirely to yourself, but if you are in the company of a friend you will belong only half to yourself’….”

Twenty D46 racers ready for delivery

Giacosa’s idea of designing a chassis made up from thin tubes had the advantages of lightness, minimal waste of space, and optimal torsional rigidity. But there was another factor, the ease of production; the workers at the Cisitalia / Beltrame bicycle plant were experts at welding tubes.

The independent front suspension was based on that of the Fiat 500, utilizing twin transverse leaf-springs. The brakes of the 1100 were added to this configuration. The live rear axle was turned upside down to permit a lower transmission axle. The unit was suspended by coil springs and had trailing arms connected to the chassis.

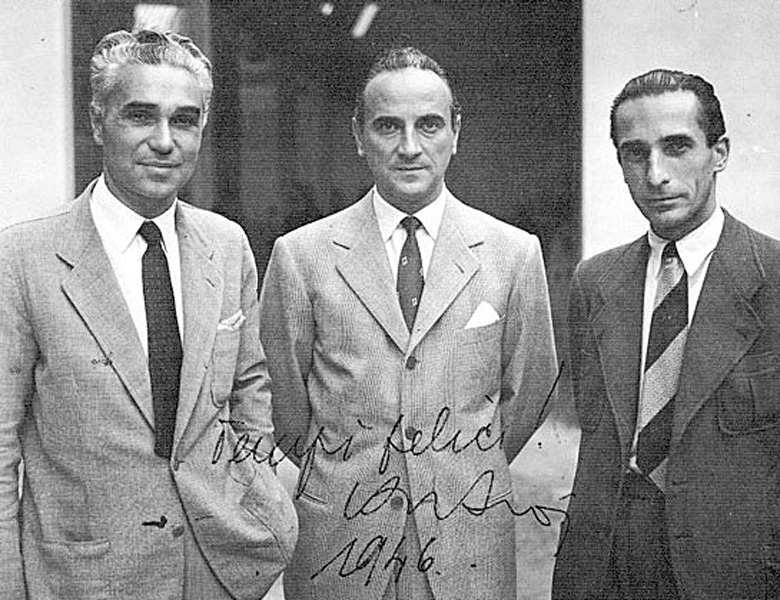

From left to right: Piero Taruffi, Piero Dusio and Giovanni Savonuzzi in 1946.The text on the photo “Tempi Felici” means ‘Happy Times”. We could not identify the handwriting and signature.

The engine received dry sump lubrication and two Weber 36 DR4 SP carburetors. The compression ratio was increased to 9.5:1, which, together with other tuning tricks, raised the power of the four-cylinder Fiat 1100 engine to 70 HP @ 5800 rpm. This output gave a top speed of just over 160 km/h (100 mph). A dry weight of only 370 kg assured a brisk acceleration.

In 1946, a batch of twenty Cisitalia monopostos, officially known as D46s, were ready for delivery. The sales price, in Italian Lira, was the equivalent of approximately 10,000 UK Pounds Sterling.

Giovanni Savonuzzi takes over

During this period, Giacosa had resumed his work at the engineering department of Fiat.

At Giacosa’s request, Dusio engaged Giovanni Savonuzzi, to help with the installation of the equipment which would be needed to test all the components. Giacosa had previously worked with Savonuzzi at Fiat’s Aero Engines Testing Division and considered him to be a creative and capable engineer. Savonuzzi also proved to be a gifted designer and stylist, who would eventually be responsible for the design of many prototypes of Cisitala roadsters and coupés.

“Did this machine just arrive from outer space or is it one of these flying automobiles”, the man with the briefcase must have asked himself. But in reality he was looking at the prototype Cisitalia Aerodynamica coupé designed by Giovanni Savonuzzi.

Most of the Cisitala bodies were handcrafted in the coachbuilding shops of Pininfarina, Stabilimenti Farina and Vignale. This practice made these elegant Italian cars rather expensive, especially when compared with the newer generation of sporting two-seaters from British and German manufacturers, such as the Jaguar XK 120 (1948), Porsche 356 (1950), Austin Healey 100 (1952), MG TF (1953) and Triumph TR-2 (1953).

The Cisitalia 202 SMM (for Spider Mille Migla) was designed by Giovanni Savonuzzii and had a body made by Carrozzeria Garella. After Tazio Nuvolari’s heroic race in the 1947 Mille Miglia, when after leading nearly to the finish, he came in second and won his class, these spiders became known as the 202 SMM Nuvolari. Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

With just 55HP to propel nearly 1000 kg (the dry weight was about 870 kg) and a gearing to allow a high cruising speed (up to160 km/h), driving a Cisitalia required the constant use of the manual four-speed gearbox. This necessity proved to be a major handicap for the North American market.

Despite their attractive styling (and Cisitalia’s impressive competition record), neither the 202 coupé nor cabriolet were commercially successful. Even in car-hungry postwar Europe, the market for such an exclusive little gem was limited. Only 170 units were sold between 1947 and 1952. The few Europeans who could afford to pay that kind of money often bought a powerful American car. Even Piero Dusio himself drove a big Buick convertible.

Without doubt the most famous of all Cisitalia Coupé models, the 202 GT by Pininfarina. It was the crowd catcher at the 1947 Villa d’Este Show in Como, and later that year at the Salon de l’Automobile Paris. In 1951, it was selected by the New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) to be part of their eight cars exhibition on the evolution of automotive design as seen in the photo above. Rightly so. Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina’s breathtaking masterpiece was to have an enormous influence on the future styling of cars on both sides of the Atlantic. The more so as several leading manufacturers, such as Alfa Romeo, BMC, Ferrari, General Motors, Lancia, Nash and Peugeot, asked him to become their consultant. Photo by Jerry Lehrer.

Argentinian adventure

Sadly, Piero Dusio saw no chance to repeat his prewar business achievements in the postwar era. He emigrated to Argentina where he tried in vain to convince the Peron government to co-finance the creation of a Grand prix car designed by Ferdinand Porsche. This overly ambitious venture cost him a fortune. In Buenos Aires, at the manufacturing plant of Autocar Argentina, he managed to set up the production of a few thousand cars under the name of P.W.O. (Proyecto Willys Overland), using Jeep engines and parts.

Dusio also acted as a consultant and liaison between American industrialists and Italian coachbuilders. One of his business contacts was Henry Ford II, who owned a Cisitalia 202 convertible and admired its design. Ford asked Dusio to develop a sporting coupé, which would be partly built in the USA, but assembled and finished in Italy. Giovanni Savonnuzi designed a couple of quite attractive prototypes with bodies made by Ghia and Vignale. Although Ford paid for these prototypes, the project was never realized.

However, one part of Dusio’s dream lives on. The few Cisitalias which still exist continue to give great pleasure to their loving owners.

A few Cisitalia related stories from the VeloceToday archives:

The complete 1100 Fiat series

I learned a ton, thank you!