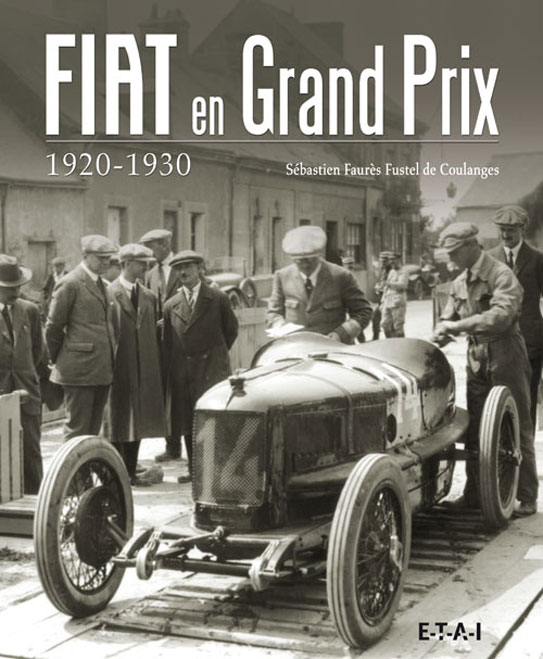

“Fiat en Grand Prix, 1920-1930”

by Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges

published by ETAI, Boulogne-Billancourt 2009

ISBN : 978-2-7268-8885-8

Hardbound with dustcover, 250 photos, 192 pages

Dimensions : 297x247x20 mm

Weight : 1340 g

Language : French

Price: 44 Euros

http://www.librairie-passionautomobile.com/Item/13_0748_this.aspx

Review by Dick Ploeg

When an introduction to a new automotive title emphasizes that the author was captivated and inspired by the late Griffith Borgeson’s The Classic Twin Cam Engine, this tribute alone is enough to arouse the interest of those who sadly miss the contributions of the great automotive historian.

Sébastien Faurès Fustel de Coulanges, in his first published book, indeed adopts a style and a treatment of his subject—interwar FIAT GP racing– that is reminiscent of Borgeson. That is to say, he provides rich historical detail and he covers complex technical material in a very accessible manner. Equally important, he focuses on the people who were involved in the production as well as the racing of the GP cars. Significant space is also dedicated to following the post-FIAT careers of such engineers as Bertarione, Becchia, Cappa, and Jano. In the main, de Coulanges gives us insight into an up-to-now hidden, but nonetheless influential, part of racing car development.

Fiat 803 at Monza. The 803 was a four cylinder DOHC with 1486cc, At Monza in 1922 four 803s started and all four finished, taking for first four places.

From about 1905 to the late-1920s, FIAT was Italy’s major contender in international Grand Prix racing and made quite a name for itself. Not only talented drivers, but most certainly an assembly of exceptional engineers and technicians, accounted for FIAT’s dominance. Ironically, one of FIAT’s contributions might be described as a move in reverse. The Henry designed DOHC engine began with 4 valves per cylinder, but FIAT engineered the return to 2 valves per cylinder that was apparently an effective enough arrangement for the supercharging program FIAT had also introduced to racing. It took a surprisingly long time, in fact, for organizations to take up multiple valve configuration again.

Such was their impact on the competition that those who tried to keep up with the pace dictated by FIAT did often not have a better solution than to copy. Some competitors went even further by hiring away talented employees who did not seem to achieve recognition while at work for FIAT. Vittorio Jano, for example, was lured away by Alfa Romeo, and Louis Coatalen snatched up Vincenzo Bertarione and Walter Becchia for his Sunbeam Talbot Darracq operation.

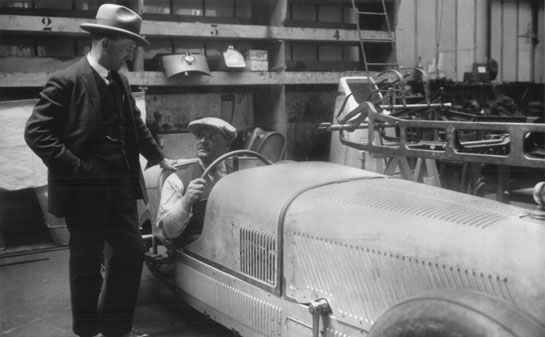

FIAT 805 with the great Pietro Bordino at the wheel. Carlo Salamano won the 1923 Itaian Grand Prix at a average speed of 91.03 mph.

Then, however, as dominant as FIAT’s position had been in international GP racing, as suddenly came its ending. Drivers were dying in a sport proving ever more dangerous. Evasio Lampiano, Biagio Nazzaro, Enrico Giaccone, Ugo Sivocci, and Onesimo Marchisio had all succumbed. Upon the death of Pietro Bordino (who died testing a Bugatti), Giovanni Agnelli decided that he had lost too many star drivers, whereupon he halted the racing program and ordered the destruction of all FIAT’s racing cars by the end of the 1927 racing season.

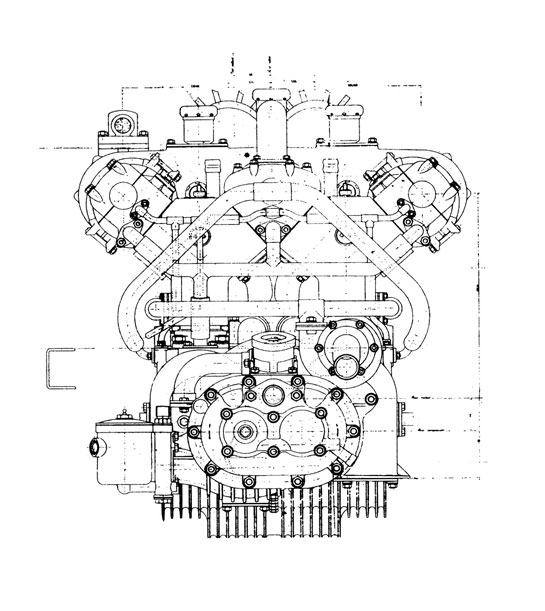

Fiat 406 engine; The ultimate Fiat Grand Prix unit, 12 cylinder (two 6 cylinders in parallel), three OHC, 1484cc Supercharged.

De Coulanges’ research is impeccable. He acquired much of his information and documentation through contacts with descendants of the original members of the company. He refreshingly uses well proportioned asides, which elucidate points raised in the text. The book is profusely illustrated with many until now unavailable photographs–almost all period images—and sectional drawings of engines and cars. This is more than a coffee table book or a compendium of photographs.

Also welcome are the frequent references to patent specifications, especially for those who like to dig even deeper into automotive engineering by consulting the esp@cenet databases on the internet. But patent literature, a neglected source of historical automotive information, can offer important knowledge to a much larger audience than engineers and patent attorneys (in the world of firearms historians, by contrast, patent documents are a common research resource). Patent documents help in establishing when a particular construction was developed and what features of a construction were regarded as important at the time. De Coulanges admirably refers to these patent documents in a notation that is compatible with and accepted by the patent profession.

Of course, no one text can cover all the possible material, so one limitation to De Coulanges’ research may be found in his discussion of the origins of hemispherical combustion chambers with valves at a V-angle and with overhead camshafts. The hemi-combustion chamber pre-dated the adoption by FIAT and was likely pioneered by the Belgian carmaker Pipe. Early Benz engines are reported also to have used it, as did the American Welch car (dating back to 1905), which also had an overhead cam.

Nonetheless, de Coulanges’ depth of coverage of his subject is such that what had seemed lost for many years suddenly has become tangible as missing links in the history of racing car development. It is only right that de Coulanges received the Society of Automotive Historians’ 2010 Cugnot Award for the best automotive book in a language other than English.

This is a highly recommended book for those interested in the history of racing car development who have mastered sufficient French, but also well worth to wait for in an English translation that this book more than deserves.

I find it interesting that this book says that Fiat was Italy’s premier Grand Prix car until the late 1920s when Alfa’s P2 obliterated it in its first race in 1924; and according to Alfa history, Fiat immediately pulled out of racing rather than try to equal Jano’s achievement. The P2 was certainly the main contender after its introduction; and won the first World Championship in its first year, 1924, which gave Alfa the right to put the wreath around its badge. I don’t know which story is correct, but I don’t know why historians have so many different versions. I personally believe that between Ferrari, Jano and the P2, I’ll believe the Alfa version.

Gary,

The 1920s was one of the most technologically interesting decades of over 100 years of Grand Prix racing; also one of the most confusing and ignored. We really appreciate your comment and hope that we have spurred interest in that decade, for in the next few months VeloceToday will be featuring much more about the cars and technologies of those pace setting years. To quickly address your comment…You are correct–Alfa’s P2 did indeed defeat the Fiats in 1924. The P2, however was virtually an improved Fiat 805. When Fiat’s Bordino saw the Jano (himself fresh from the Fiat engineering staff) designed Alfas, he quipped “Eh, if you need spare parts, just come and ask us.” Fiat did not actively compete in the Grand Prix events in 1925 and 1926 for a variety of reasons. When Fiat did return in 1927, they introduced the complex three cam U 12 806, which won its first and only race, the Milan Grand Prix, on September 4th, Bordino up. After the event Fiat retired from racing.

Ed.

I am trying to find any info on the `fiat 561 gp car, especially date built