Count Johnny Lurani envisioned a class of Italian cars that would both train new drivers and allow the Italian artisans to show their stuff. And for a few wonderful years that was true. Italian open wheeled Etceterinis, most powered by Fiat engines located in front, as had been the prevailing custom for the previous fifty years, won every Formula Junior race around the world. It was Formula Junior the way we liked it. Italian historian Alessandro Silva addresses these years in a new and very welcome book published by Fondazione Negri. Aldo Zana, no stranger to VeloceToday, reviews it below.

Review by Aldo Zana

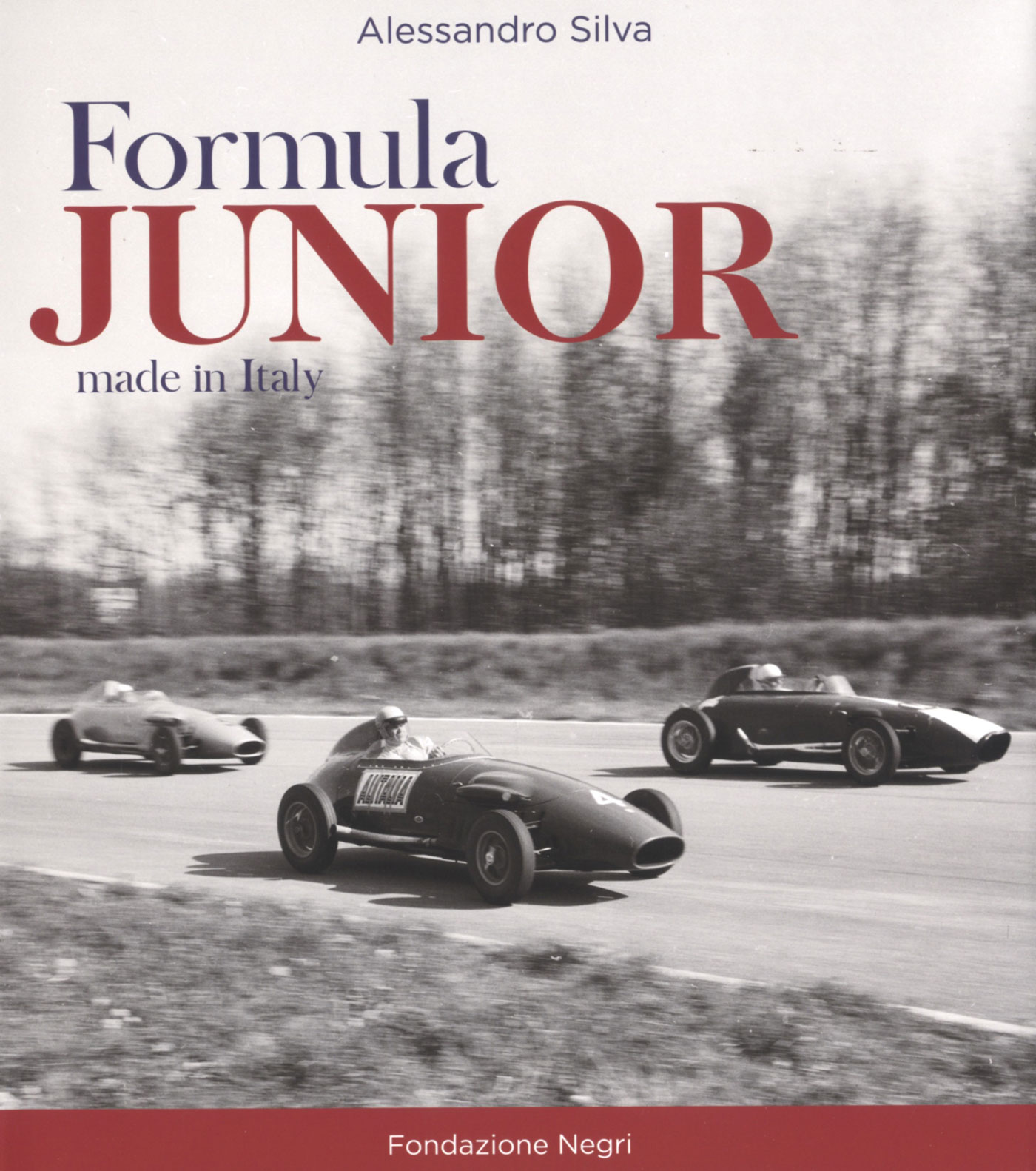

Alessandro Silva: “Formula Junior Made in Italy”. Fondazione Negri, Brescia (Italy) 2021. 256 pages, 9.5”x11.7”, hardbound w/dust cover.

ISBN: 978-88-89108-43-7. Price: euro 48.00

No other racing car category is as Italian as the Formula Junior, established early 1958 by Johnny Lurani Cernuschi, a Count with a long and remarkable experience as racing driver, journalist, speed record-holder.

The FJ category became an immediate success in Italy and quickly emerged as the internationally recognized entry level standard in single-seater racing. The original charter set strict boundaries on engines, suspensions, frames and maximum weight. Engines had to be taken from mass production and tuned to deliver the output (75-90 HP) needed for a competitive racer. Maximum capacity of the engine was 1,100 cc, the standard displacement of the best-selling family cars in Italy and the rest of Europe.

The new formula opened a new market to domestic artisans manufacturing racing cars (the American “Etceterini”), promising a strong, nearly explosive, growth. The story of the origin, success, and demise of the Italian-made FJ racers and races is now detailed in a new book by Alessandro Silva, a director of AISA (Italian Motor History Association) and a member of the inner circle of the leading Italian motor racing historians. He also authored “Back on Track”, the fundamental work on formula racing seasons covering the period from immediately after WW2 through the first F1 World Championship in 1950.

The book, published by Fondazione Negri, is written in English (a separate Italian edition is also available) and details the subject in 256 large-format pages enriched by 237 B/W period photos. It lists all the Italian marques through each of their models, detailed with technical specifications and dimensions. The number of cars produced and still in existence today is mentioned whenever reliable data could be sourced. Serial numbers are also listed. The preface is authored by Duncan Rabagliati, the Briton historian-organizer of the FJ FIA Historic Races.

Race recaps and results are published in sections organized per year and country. America is well covered since the early exhibition events in 1959 and the first SCCA National Championship in 1960. It could be surprising to find among the starters and winners in FJ races quite the crowd of well-known names, the likes of Jim Hall, Ken Miles, Denise McCluggage, Ed Hugus, Jim Rathmann, Rodger Ward, Peter Revson, Pedro and Ricardo Rodriguez, Jerry Titus, Briggs Cunningham, Augie Pabst, Walt Hasgent, Roger Penske. A Special mention goes to Charlie Kolb, who entered 41 races in the 1960 season and became national champion with 74 points ahead of Harry Carter at 62.

The reader will also learn the names of the US importers of Italian FJ racers: Marty Biener in Great Neck, Long Island (Bandini, Dagrada, Taraschi, Volpini, Wainer); Luigi Chinetti (Osca); Alfred Momo (Stanguellini); Ed Hugus (De Tomaso).

The racing scenario drastically changed beginning in 1961, when the Italian front-engined FJ racers were outclassed by the rear-engined British single-seaters thanks to their innovative, advanced architecture and the more powerful Cosworth engines. The writing was on the wall for the Made in Italy category, as the new formula opened up to a new generation of small racing cars.

A rare bird, the BB-Fiat driven by Alberto Canali before the start of the July 15, 1962 Vinci-San Baronto hillclimb in Tuscany. The BB might be the initials of Branca, car builder, and Bandini, tuner of the Fiat 1100 engine.

The appendices list the significant victories of each marque; feature succinct biographies of the drivers (non-FJ key achievements are also mentioned); provide the racing numbers given to each driver for the Italian races, 166 in total. The Index of names, alas, repeats the questionable layout of “Back on Track”: i.e., no mention of the actual page but merely a reference to the chapter and section, thus devoiding it of any usefulness.