Panhard: the Dynamic was made from 1936-9. It was the largest unibody car made at that time, with the steering wheel in the center of the dashboard. Even today, the styling is very dramatic!

Story by Brandes Elitch

Photos courtesy of the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum

At Retromobile, a few years ago, I picked up a copy of “Le Guide: Musees Automobiles de France,” published by the magazine “Auto Passion.” The guide covers 36 car museums. Some are well known: the museum at the LeMans circuit, the Schumpf (their equivalent of a National Motor Museum), Le Manoir, near Rennes, the Cadillac museum near Tours, the Henri Malartre museum, housed in an old mansion, near Lyon. I’ve seen all of these, and they are definitely worth seeing. But as it turns out, you can visit one of the most outstanding French car museums, without even leaving the US. That’s because it is located on the west coast of Florida – the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum.

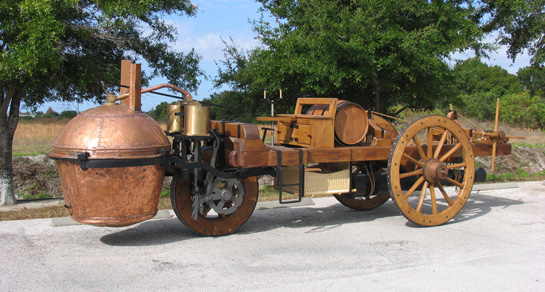

There are videos and signboards to explain why each selection deserves inclusion in this esteemed group. Some are obvious, others not so much. This is not as easy as it might seem. For instance, the first motorized vehicle is the Cugnot steam carriage, a project started in 1760 and finished ten years later, for the French Army. If you were really serious about showing the technical evolution of the automobile, you would start with this. There is only one problem: just one was made, and it is in a Parisian state museum. Mr. Cerf found an exact, and I mean exact, reproduction, made in Germany in 1935 for a movie, bought it, restored it, and actually drives it around the museum grounds. You can watch video clips from the movie as you study this contraption, and marvel that it could actually move without falling over. He has even written a 100 page book on it. This project deserves a separate column, which is forthcoming.

'The idea of a collection based upon avant-garde automobile technology grew stronger everyday ...our goal is to present the engineers, many virtually unknown to the layman, whose imagination and dreams created technology commonly used in the automobile industry today.'- - a quote from founder Alain Cerf

It turns out that, while the French automobile industry produced very innovative products, not all the inventors were French themselves. Mr. Cerf presents what he calls the Yin and the Yang of automotive technology: Hans Ledwinka and Jean-Albert Gregoire. But he doesn’t stop there. Other designers whose work is displayed include Jaray, Muller, Rasmussen, Rohr, and Porsche. He also talks about the creative process itself. As he says, “It was common for 6, 10, or 12 engineers, technicians, and draftsmen to undertake studies to design a prototype ready for the road in a year or less, without the help of CAD systems, computers, or even electronic calculators. These engineers, either by schooling or by trade, were the ferment necessary to a new industry in full expansion…Our goal is to present some of these engineers, many of whom are virtually unknown to the layman…Their imagination and dreams created technology commonly used in the automobile industry today.”

Fifteen years ago, Mr. Cerf started to build the museum collection to honor the dozen engineers who contributed so much to the automobile. I said that he is a detective, and one example is the 170 page text he has written on Dimitri Sensaud de Lavaud, a French engineer with over 250 patents, including the first hydraulic transmission for a car. For many years, the “conventional wisdom” was that the Citroen Traction Avant first year production was cursed by an unreliable automatic transmission promoted by Andre Citroen. Mr. Cerf demolishes this argument in a highly detailed piece of original research that must have taken him ten years to assemble. It is such an interesting story that you can appreciate it just from the human interest standpoint, nor do you have to be a Citroeniste (like me) to appreciate this remarkable research project.

In addition to the Cugnot, there are sections on the designers of the 1920’s and 1930’s, front wheel drive, the Knight sleeve valve motor, rear engined cars, and Claveau. Some of the cars displayed include Darl’mat, Delage, Citroen, Tracta, Tatra, Alvis (fwd), Talbot, Panhard, Ruxton, Cord, Gregoire, Amilcar, Hotchkiss, Chenard-Walcker, BSA, Adler, DKW, Aero, Voisin, Mercedes, Delahaye, and Salmson, about 45 vehicles in total. All the cars have been restored to a high standard. What is remarkable is that, unlike most museums, which are devoted to nostalgia for an era or place, this is really a history of the technical evolution of automotive design. In assembling such a collection, it is almost as difficult to figure out what to leave out as what to leave in, but all in all, I think Mr. Cerf has done a remarkable job (although I wonder why there is no DS on display!).

The museum is located adjacent to Mr. Cerf’s business, a packaging company called Polypack. It is located in Pinellas Park, only a few miles from the Tampa Airport. You can find out more at www.tbauto.org. This museum is fully the equal of anything in France (well except the Schlumpf, but what can be compared to that?) and should be on your list of “must-see” automotive experiences for any serious automotive enthusiast.

Tracta: in 1926, Piere Fenaille invented a constant velocity joint under the name of Tracta. Fenaille and Gregoire produced the Tracta, and Gregoire drove the collection's supercharged Tracta at LeMans in 1929 and 1930. The Tracta CV joint was used during WW II in Ford and Dodge jeeps and command cars, and the Germans and Russians used them too (they just didn't pay the licensing fee!).

Voisin: Gabriel Voisin was trained as an architect, but he was mainly an aircraft designer, which is where he made his money. He was primarily interested in women; however he also designed and built some very spectacular and expensive automobiles, using the Knight sleeve valve engine.

Darlmat was a Peugeot dealer in Paris, who decided to make a run of custom bodied cars based on the Peugeot drivetrain. Only around a hundred were made, many styled by dentist George Paulin, and bodied by Pourtout. After laboring in obscurity for decades, they are now considered very desirable and valuable cars.

Citroen Half-track. Andre Citroen was a brilliant marketer. He conceived of the idea of crossing previously unexplored territories with a caravan of half-tracked vehicles. The most famous are 'la croisiere jaune' and 'la croisiere noire,' two of the greatest expeditions in world history.

Cugnot. This is an exacting reproduction of the Cugnot steam carriage, built in 1770 and in a Parisian state museum. It was designed to haul heavy guns and artillery for the military. We can say that Cugnot was the first true automobile engineer. The museum will occasionally fire it up and drive it around the museum grounds!

Mr. Cerf’s museum is reminiscent of the former Cunningham collection in Costa Mesa, Ca. is that each car has a significant technical history and lighting that allows the visitor to see the details of the automobile. This lighting is in contrast to the Las Vegas theater lighting in many newer hoy poloy automotive museums where only the outline of the car is visible.

Our club, Les Amis de Panhard et Deutsch-Bonnet, visited Mr. Cerf’s museum in May of 2009. We were blessed by a personally guided tour of his wonderful collection. He was a wonderful host and truly loves his cars!

I heartily encourage anyone visiting the Tampa Bay area to put this on your ‘must-see’ list.

I had the pleisure to meet Mr Cerf on Retromobile this year, where he exposed his Cugnot Replica. In fact, his Cugnot Steam Carriage (“Fardier”) is not only an exact reproduction, but also a piece of exact historic research. Since the original Cugnot, which is exposed at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, is not in running order, he and his team had to find out how exactly it would have worked, retracing some of Cugnot’s forgotten inventions.In fact, he even showed that the parisian Fardier must have suffered from several bricolages over the past 200 years.

To build the new, working replica, he borrowed the german 1930’s replica from the Deutsche Bahn Museum in Nuremberg and took measurements. The Fardier was then built from scratch, bringing together CAD-systems and traditional handcraft. All the work and the history is described in a book surely deserving a review

Hi – Loved your Chenard et Walcker Super Eagle. I had one until I sold it to another Brit in the south of France a few years ago. Mine was refurbished in and out with a bench seat in the front and a drinks cabinet for the rear passengers.