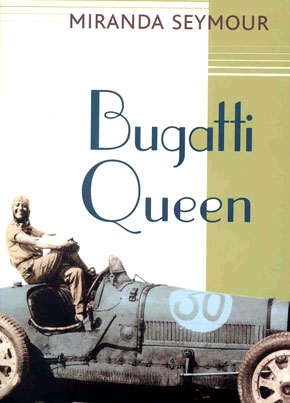

January 2002, New Jersey. Miranda Seymour, a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and visiting professor at the Nottingham Trent University, climbed into the cockpit of a Bugatti Type 35C, then owned by noted car collector Oscar Davis. It was the first time the celebrated biographer of Mary Shelley, Robert Graves, and Henry James ever sat in a race car.

What Miranda Seymour knew about cars, racing, Bugattis and Alfas wouldn’t fill a float bowl; as far as she was concerned, a straight-eight might be some kind of cocktail. Nevertheless, Seymour was about to embark upon a two year quest in search of a French dancer turned-race car driver who caught the world’s attention in the early 1930s. Seymour’s fifth biography, published by Random House, would be titled “Bugatti Queen” and bring forth the ghost of the sexy, mysterious, and ill-fated Hellé Nice.

Stymied by the technical aspects of cars and racing, Seymour sought help. Patricia Lee Yongue, an Associate Professor of English at the University of Houston who also writes about Bugattis, became a regular email correspondent. “Miranda read deeply and asked questions of many people about Bugattis and Alfas as performance cars,” said Yongue. “She wanted to know the cars almost as much as she wanted to know Hellé Nice.”

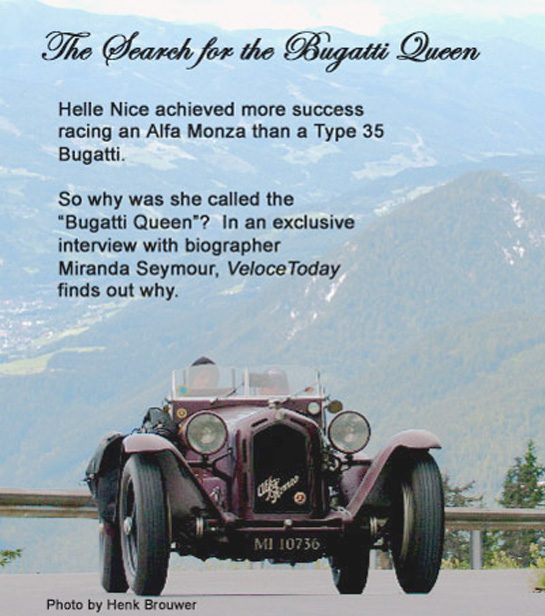

Monza vs Bugatti

Nice competed with both Bugattis and an Alfa Romeo Monza, in fact garnering more success with the Alfa. Perhaps the title should have been “Alfa Queen” but that strikes a discord. Seymour was partial to Bugattis. “The Alfa Monza is a more powerful car, but it’s not a pretty one”, she said. “You can’t fall in love with a Monza. You can’t fall anything BUT head over heels for a Bugatti 35B.” She is also convinced that “Ettore Bugatti was eager to sell cars to women,” and, coincidentally, “Nice wanted to show her skill driving against men.” Hence, Bugatti Queen it was.

Some have doubted whether or not this French upstart deserved the title of Bugatti Queen, which perhaps could have more aptly described Elizabeth Junek, an extremely successful Czech who also raced Type 35 Bugattis from 1926 to 1930. Ironically, Junek totally serious about her cars and her racing probably would have hated the theatrical epithet.

Some have doubted whether or not this French upstart deserved the title of Bugatti Queen, which perhaps could have more aptly described Elizabeth Junek, an extremely successful Czech who also raced Type 35 Bugattis from 1926 to 1930. Ironically, Junek totally serious about her cars and her racing probably would have hated the theatrical epithet.

Charming Charlatan?

It has been suggested that Hellé Nice was perhaps more of a poseur, a charlatan in the game for publicity and glory. There is some truth to the allegations. Michael T. Lynch, noted historian, perceives Hellé Nice from a different perspective. “As a fifty year student of motor racing history, I don’t quite understand how Nice can now be presented as one of the great women drivers of the 20th century. My own impression is that, had it not been for her rather adventurous love life, she would have continued to languish in obscurity.”

________________________________________________________________

Please show your support for VeloceToday and subscribe (or re-subscribe if you already receive VeloceToday). Click here..it’s easy!

________________________________________________________________

Her reputation was questionable. Prior to driving race cars, Nice was a show girl, dancer, model and “personality”. Off track, she flaunted her charms and looks, and flirted with everyone. Her affairs were so numerous Seymour wisely left most out of the book. Nice never married and never had children. If not ahead of the pack, she was ahead of her time.

Nevertheless, her impressive performances behind the wheel belied a superficial interest in competition. From 1929 to 1936 when an accident in Sao Paulo effectively ended her career, Nice entered more than forty international events driving Bugattis and the Alfa Monza. In 1931, she spent six months on tour of the US, demonstrating her talents on the lethal oval tracks, driving a Miller in exhibitions.

She traded up from Bugattis to an Alfa Romeo Monza in late 1933 and began the most competitive phase of her years of driving. These were not powder puff derbies; she was a professional, making a living behind the wheel, running wheel to wheel with the men.

Until Seymour’s book, little was known about Hellé Nice. Who she was, where she was from, when she died, and what she drove were unanswered questions. After WWII, she seemed to vanish, under strange and tragic circumstances.

Nestled in the cockpit of Oscar Davis’s Bugatti, (currently owned by Brian Brunkhorst) Seymour was thrilled, for it was believed to be the Bugatti Hellé Nice had driven to a world record at Montlhery in 1929. Now, after months trying to contact Davis, Seymour’s persistence finally paid off. “Just get on a plane and come to New York”, wrote Davis. “Oscar turned up at my hotel to meet me, cute and twinkly, with a gorgeous old Jaguar in which he swept me off to his garage and showed me Hellé’s car, the prettiest, sexiest little blue 35B. It was a shock to take in the fact that Hellé Nice had to drive with a gear stick outside of the car, with a clear view of the road through the bottom of the car, with a steering wheel that handled light as thoroughbred’s reins and with a top speed of 220 kms an hour.”

Seymour had not crossed the Atlantic just to sit in a Bugatti. Davis had also acquired the scrapbooks of Hellé Nice, which were sold in a flea market sale after her death. “Oscar gave me the run of the albums and told me he would have full copies made so I could work from them at home.” Seymour now had access to the first of four remarkable packages of documents that would enable her to bring her subject into focus.

Nice’s scrapbooks had been sold at a flea market after her death, and had found their way into the hands of Oscar Davis. A collection of photos was also sold at the same time, and after waiting and watching, Seymour found they were with a collector named Wolfgang Stamm. The photos included a photograph of Hellé “draped in a scarf and nothing else”.

Finding that Hellé had rented a room in the dreary side of Nice, France, Seymour paid a visit the daughter of the landlord, Andrée Agostinucci. The landlord’s daughter brought out a trunk which contained “the stuff of which biographer’s dreams are made”. Letters, notes, more clippings, more photos, amounting to an in depth look at the personal life of Hellé Nice, aka Helene Delangle, of Aunay-sou-Auneau, a hamlet near Chartres. Agostinucci happily agreed to assist Seymour, and suggested she also check with another source, Mme. Jarnach, who, as it turned out, was an old friend and benefactor. She held the other end of many letters, the ones written rather than received by Nice.

Finding and obtaining rights to the material is one thing, but writing a book which would please both the cognoscenti and the average reader is another. When it was published in 2004, “Bugatti Queen” brought a fresh voice to the often stodgy world of automotive history. Seymour admits it was a challenge “…there certainly was a major difficulty in trying to bridge the worlds of the connoisseurs and enthusiasts, and the readers who knew nothing of cars but were intrigued by the story of a daring and adventurous woman.”

Finding the truth is yet another matter. The story of Hellé Nice ended quietly but tragically in her cold, tiny apartment in 1984. Poor, with no more friends, no family, with only her mementos and scrapbooks to recall a famous past, Nice died, still in disgrace. While the devastating accident in Sao Paulo nearly destroyed her physically, the aftermath of WWII destroyed what was left of her psyche. In 1946, at a party in Monte Carlo, French racing champion Louis Chiron accused Nice of collaborating with the Nazis.

Chiron and Nice were the same age, had raced the same cars and in some respects, suffered the same ill fortune in the later 30s. Nice had her accident and Chiron’s cars were unable to compete with the German Mercedes Benz and Auto Union teams. It is still unknown why Chiron decided to blatantly accuse Nice of collaboration, and no hard evidence was ever found to support his claim. Had the accusation been made by a driver of lesser stature or renown, it may have passed as gossip. But Chiron was a veteran, still driving for Talbot, and a French hero. His words had power at a time when a mere hint of Nazi collaboration might mean the death penalty. Male ego, nastiness, jealousy, revenge? None seem to apply; did Chiron know something never to be discovered?

Seymour provides ample background to the accusation, and requested that the German Bundesarchiv look for any records that might implicate Nice, or Delangle, as a German agent. As thorough as the Germans are, they concluded that Hellé Nice or Helene Delangle was not a German agent. But 60 years after the end of the war, the issue is still as volatile as it is mysterious.

Thank you for a very interesting piece. I knew nothing of this story, and was fascinated by your report.

I will have to read this book – if I can find a copy