By Nigel Trow

Sigmund Freud, Vincenzo Lancia’s older contemporary, would have had much to say about the life of Lancia’s son, Gianni, who died on June 30th 2014 at his home on Cap Ferrat, France. Born in Turin in November 1924, Gianni was the middle child of three and the only son of Vincenzo and Adele Lancia. The children were close in age; Anna Maria, the eldest, being born in 1922 and Eleonora, in 1926 (tragically murdered by her disturbed daughter in 1996). They were left fatherless in their early teens by Vincenzo’s sudden death in February 1937, and for Gianni, not yet 13 years old, the prospect of having to take his father’s place must have loomed large.

His mother, Adele was quickly appointed Chairman of the company. This strong and competent woman, ably supported by a group of senior managers, took control at a difficult time. Lancia’s latest car, the innovative and independently sprung Aprilia with a new V4, had been launched only a few months earlier at the Paris Motor Show in late 1936; a new foundry and truck factory was coming on stream in Bolzano, far from Turin, near the Austrian border; Mussolini was dragging Italy into wars in Spain and Ethiopia, involving Lancia in military production in the process, and beyond the Alps Hitler’s German version of Fascism threatened all of Europe. Not a promising time for a newly widowed mother of adolescents to assume the burden of a great industrial company!

When the Second World War finally came to Italy, Lancia’s factories were on the Allied hit list; Turin and Bolzano both suffered severe bomb damage in the early 1940s. Gianni, now of university age was enrolled by his mother in the old, prestigious University of Pisa to study engineering. It was not a good place to be once war began, the city suffering particularly heavy bombing in the autumn of 1943. According to Luigi de Virgilio and Guido Rosani he probably started in 1944 and lived in the Hotel Cavalieri, sometimes travelling back to Turin by road in the type 538-engined Aprilia prototype. The five-year engineering course must have been even more fragmented than Pisa itself. Young Lancia would not have found it easy, particularly since he was inevitably becoming involved with Lancia management under the tutelage of his uncle, Arturo Lancia, who had returned to Turin from the United States in 1944 following a successful management career in the automobile industry. Gianni had yet to complete his degree when he was appointed joint managing director in 1947, a significant role for one so young, and was not to graduate until after 1948, following Arturo’s death when he found himself at the very top of Lancia’s tree. He is reputed to have presented a paper on a twin cylinder engine for his laureate, a design rejected by his professor until told by Gianni that it was already running in Lancia’s experimental workshops.

Italy was beginning to emerge out of the war’s disaster by the late 1940s. Bomb damage to the factories had been more or less repaired and Aprilia, Ardea and truck production was increasing. Money was tight, however, and because of Gianni’s student sympathies for the left wing resistance movement (probably derived from his time in Pisa, where the university had a long tradition of anti-fascist politics) Lancia was effectively denied Marshall Aid monies, receiving a measly $800,000. Nevertheless, the company was far from impoverished. Despite some resistance from older members of the management board, Gianni set about introducing a new car derived from research undertaken in Padova during the war years.

In 1937 Vincenzo Lancia had appointed the great Alfa Romeo engineer, Vittorio Jano, as Technical Director. About the same time a younger engineer named Francesco de Virgilio also joined the firm and in the 1940s set about solving the balance problems presented by a 39º V6 engine currently under investigation. Lancia had toyed with such a configuration at the time of the Lambda, but this had come to nothing more than a stretched, narrow V6 prototype. The resurrected engine went through various V angles before de Virgilio settled on 60º, the form made famous by Gianni’s new car, the Aurelia. Typically Lancia, this five seat pillarless saloon carried forward the thinking behind the Aprilia in a quietly clever way, with a new and simple independent rear suspension to compliment the traditional sliding pillar front, and a smooth 1750cc V6 engine that broke wholly new ground.

The Aurelia was Gianni's Lancia. This is Marcello Minerbi's B12 on the Lancia Route 66 Tour in 2006. Photo by Cory Youngberg.

When the Aurelia was launched at the Turin International Automobile Salon in 1950, Gianni and his mother Adele found themselves with another Lancia success to add to Vincenzo’s previous achievements. 1950 was also the year of Gianni’s marriage to Luisa Magliola, and the young man’s self confidence rose.

In his own youth, Vincenzo Lancia had earned a considerable international reputation as a racing driver but abandoned it when he became a manufacturer. In fact, he seems to have acquired an antipathy to motor sport, only occasionally endorsing it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, son Gianni became a supporter. With the B10 saloon on the market and a small team of 2 liter B21 versions performing well in the 1951 Giro di Sicilia, he had a batch of 50 fast-back coupes produced at Ghia and Viotti to test the waters for a Lancia GT car. These 2 liter B20s lit a fuse. On April 29, 1951, Giovanni Bracco and Umberto Maglioli did something previously unheard of in the Mille Miglia. In a race usually dominated by outright speed they took this untried little Lancia, capable of no more than 160 kph, and finished second to Villoresi’s 4.2 liter 340 Ferrari, having led for much of the rain sodden race. Six other Aurelias were among the top 18 finishers. After that it was a case of Gianni unconstrained.

Over the next two years he ordered the building and racing of a team of six 2 liter lightweight B20s, followed by six GT2500 cars and the production of a sequence of V6 twin-cam sports racing cars and a V8 GP single seater – the D series – that were to be the basis of a serious attack on international motor racing. This was a young man’s gamble, done in the face of further opposition from other experienced heads on the Lancia board.

Yet Gianni probably had good reason to take risks. Though the company was getting back to normal, the new industrial world looked towards America, despite continued efforts by the Italian left to face Moscow. Before the war his father had worked hard to expand the company internationally, with outposts in London and Paris, and several failed attempts to break in to the U.S. market. Gianni, like Ferrari and the Orsis at Maserati, also saw transatlantic business as important, and like them felt motor racing success to be an important promoter of sales. So he went for it in a big way. Not only was he spending lavishly on racing but at the same time he commissioned Nino Rosani, the company architect, to build new headquarters on the site of the factory in Turin’s Borgo San Paolo district. The result was the city’s first skyscraper, the tallest building other than Turin’s Eiffel Tower, the Mole. What he failed to do, however, was sort out Lancia’s confused production facilities.

The first 2.9 liter D20 coupes, derived largely from Aurelia practice but without the old fashioned sliding pillar front suspension, ran in the 1953 Mille Miglia, where Bonetto and Peruzzi finished third, and Biondetti and Bavareno eighth. Gianni, satisfied with such a first time result, returned optimistically to Turin. A month later in Sicily his confidence was further boosted by Magioli’s Targa Florio victory in the D20, but in pouring rain the cockpit inadequacies of the closed coupe had been only too clear. By the middle of the year an open replacement, the D23, was ready and two months later the great D24 made its debut at the Nurburgring in the ADAC 1000Km race on August 30. Two cars, driven by Fango/Bonetto and Manzon/Taruffi, together with a D20 for Bracco/Castellotti, started but failed to finish, despite having Gianni in the pits as team supremo.

But the sports cars were just the warm up for Lancia’s Grand Prix aspirations. The radical short wheelbase, pannier-tanked, low-polar moment, V8-engined D50 single-seater designed by Vittorio Jano had taken much longer to develop than had been hoped. It was a design ahead of its tires, and Ascari and Villoresi, signed up by Gianni long before the car was ready, had a hard time sorting out its wayward handling. Not until late 1954, after several aborted entries, did it make its first racing start in the Spanish Grand Prix in Barcelona, where both D50s entered for Ascari and Villoresi retired after Ascari had taken pole but lost his clutch after leading for 10 laps. Villoresi completed only three before pulling out with no brakes. Similar difficulties sidelined the three cars sent to Argentina for the first GP of 1955. It was not until the Turin GP that Ascari managed to win, with Villoresi third.

Eugenio Castellotti at the wheel of the Lancia-Ferrari at the 1956 British Grand Prix at Silverstone. Photo by Graham Gauld.

Behind the scenes, Lancia was sinking deeper and deeper into trouble. Cars and trucks were still being built to high standards, but the costs of production were too great. Discussions about selling up were taking place, but not all of the family shareholders agreed that this should happen. Gianni and his two sisters fell out. He may well have been negotiating to sell his holding without involving them, and it is believed that one of them was certainly opposed to any sale. His mother, Adele, still company chairman, probably sided with him and matters came to a head in mid-1955, immediately after the death of Alberto Ascari. Having survived a ducking at Monaco when he crashed his D50 into the harbor in what was Lancia’s final official outing, Ascari was killed in a banal, unnecessary accident at Monza in a Ferrari. It was a tragic end to both driver and company.

The public finale was sudden. Gianni, his business and his marriage in a state of collapse, flew to Brazil accompanied by his mother. The D50s, after one final outing in the hands of Castellotti at Spa, were bundled off to a needy but ungrateful Enzo Ferrari, together with a Fiat handout. Control of the Lancia Company passed to Carlo Pesenti, a cement magnate whose concrete had built the skyscraper. Sic transit gloria Lancia.

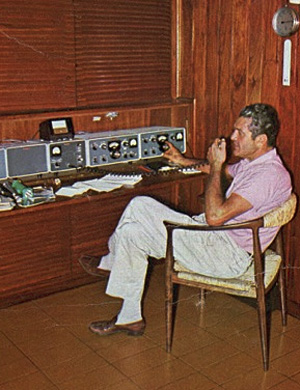

In Brazil, like one of Joseph Conrad’s anti-heroes, Gianni travelled by canoe into the green heart of the Mato Grosso, largely inaccessible by any other means in 1955. There he purchased land and set about a new life as a rancher, clearing ground, building a house, and buying cattle, indirectly mimicking his grandfather, Giuseppe, who made his fortune in Argentina in the mid-19th century as a meat canner. He also bought a light aircraft in which he flew thousands of hours covering the vast territory. He was no recluse, however, returning regularly to Europe where he still had business dealings, some of which landed him in court in the 1960s when a couple of British banks called in a surety he had provided to a pair of Englishmen involved in a sisal business in Kenya. Gianni got around.At the end of the decade he married again, this time to the French actress Jaqueline Sassard whom he met in Brazil. They had one son, and acquired the house in Cap Ferrat where he died. He also owned a palazzo in Turin and was in touch with others of his family.

Gianni Lancia was buried in Fobello, the Lancia family’s ancestral home, and is survived by his wife, three children, and grandchildren Carlotta, Maria Luisa, Gianna, Roberta, Umberta and Edoardo.

Nigel Trow has done it again – an interesting, concise yet detailed story about this key phase in Lancia history and of man about whom we know now more but not enough. Let us hope more may emerge from Italy and elsewhere in due course.

Geoff Goldberg’s book being published so close to this event makes it a memorable month. And then there are the auctions in California….

Paul Mayo

Paul,

We are very happy that finally Nigel seems to be aboard. Also. we hope to get Nigel to review Geoff’s great new book, which we both have received already. In the meantime, don’t hesitate to order your copy from David Bull while they last!!

The Editor

“….Because of Gianni’s student sympathies for the left wing resistance movement Lancia was effectively denied Marshall Aid monies, receiving a measly $800,000…..”

Mr.Trow, this isn’t true!

You must to study the history of this period better, reading the company ledgers for example, where you can find that Lancia received a loan of 1.5 million dollars from the EX-IM Bank and a loan of 1.62 million dollars from the European Recovery Program in 3 different portions. I documented everything here:

http://www.viva-lancia.com/lancia_fora/read.php?337,1233326

Props to VT for bringing Nigel Trow on board. Looking forward to more from him!

Great work, Nigel! I look forward to more. Much yet to learn.

Pete

Tremendously interesting account of his life

I remember very well when Lancia entered sports car racing in first year of world championship and then into Grand Prix racing 1954, their debut being spectactular.

This prompted my dear friend Denis Jenkinson to write, ” Lancia,,New Power in the Land.” Indeed, they hired world champion Alberto Ascari away from Ferrari at big increase in salary, which caused the old tyrant to explode of disloyality,,!

Again, my appreciation for job well done

Jim Sitz

Oregon

Well done Nigel. I look forward to meeting you in the near future.

All the best,

Chris

The Life for Lancia Familly now is very unpleasant …!!! If you see the ” Farm ” in Brazil around Rondonopolis : Farm is old … No water : Only ” Artesian Puits ” nothing climate air !!! Nothing swiming pool … With an incredibile umidity and a jungle mosquitos !!! The third son lived in This Farm and make meat business …. The father Gianni was a Heroe !!! The Farm now has a value to 350000 $ !!!…. How This familly ? …. It s so sad ….