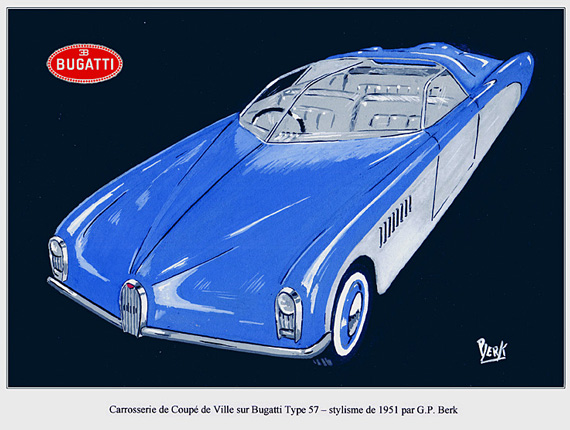

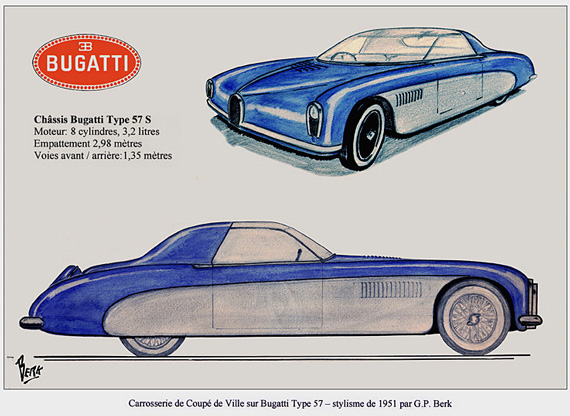

I was great a fan of Bugattis. This was one of the reasons why I designed this Coupé de Ville body for a Type 57 chassis. Of course I was inspired by the prewar designs of Jean Bugatti but tried to give the car a more modern appearance. I used the horse- shoe symbol not only as a fake radiator for the cooling intake but also as headlight covers. I did send a photocopy of these drawings to Monsieur Pierre Marco, then the Managing Director of Bugatti. However I never got a reply. Note that the headlight arrangement bore a striking resemblance to the last Saoutchik to be produced, the Pegaso SIII. Ed.

By Gijsbert-Paul Berk

Photos and drawings courtesy Author unless otherwise noted

Off to Paris with Portfolio

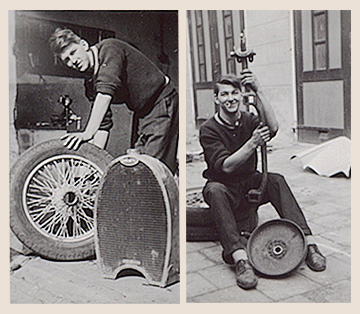

As related in Part 1, I wanted to work as am automotive designer, and became very interested in Bugattis. In fact I had the chance to restore such a car. In 1949 one of my friends discovered in the port of Rotterdam a Bugatti type 40 roadster with a Bordino type or boat tail factory body.

The car was used there as a tractor to move freight cars and in a deplorable state. But we bought it and together restored it. A 1928 four-cylinder Chevrolet machine of just over 2 liters had replaced the original 1500 cc engine. Because it functioned very well in the car and we could not find nor afford a comparable Bugatti unit we retained it. But the chassis and body were renewed bolt for bolt. It took us several months.

The car was used there as a tractor to move freight cars and in a deplorable state. But we bought it and together restored it. A 1928 four-cylinder Chevrolet machine of just over 2 liters had replaced the original 1500 cc engine. Because it functioned very well in the car and we could not find nor afford a comparable Bugatti unit we retained it. But the chassis and body were renewed bolt for bolt. It took us several months.

This did nothing to diminish my desire to become an automotive designer. Having had no luck with local coachbuilders in the Netherlands, I was at a loss until a friend of the family remembered that he knew John (Johan) Sijthoff, scion of a printing and publishing family and – more important in my case – a shareholder and director with Carrosserie Saoutchik in Paris. He organized an introduction for me.

Although Bugatti was on its last legs, designing coachwork for the legendary company was irresistible, even if on a prewar T57 chassis.

By now it was late September and after consultation with my parents and the director of the IVA, in the first week of October I took the train to Paris to visit the Salon de l’Automobile (Motor Show) and try my luck as a young automobile designer in the French capital.

In those days the leading French coachbuilders still had their own stands in the Grand Palais, so it was easy to make appointments to present my work. This way I fixed meetings with Henri Chapron, Jean-Henri Labourdette, Marius Franay and Marcel Letourneur, all of them important coachbuilders.

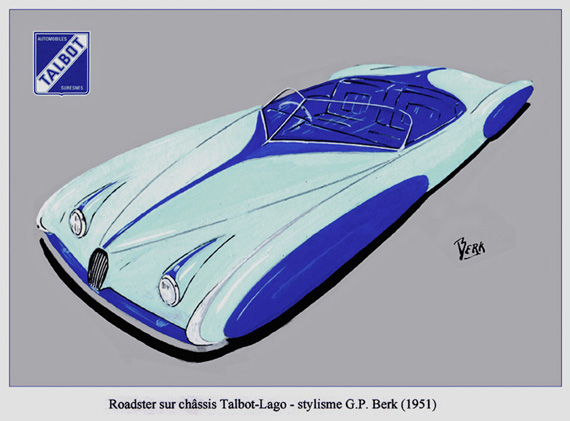

This rendering for a Lago-Talbot roadster was very much in the fashion of the French coachbuilders in the early fifties. Afterward I realized that covering front wheels with ‘spats’ was not such a good idea for a sports car as it prevented an optimal cooling of the drum brakes in the front wheels, thus diminishing their efficiency when driving on mountain roads. But it was quite popular with some the French carrossiers.

Marius Franay, was also the Président of the Chambre Syndicale de la Carrosserie Française. He and Henri Chapron explained to me that old-fashioned firms who depended on producing one-off or custom built coachwork were faced with the scarcity and therefore high wages of good craftsmen. And the fact that in France the market for expensive cars was practically wiped out by heavy taxation. In Chapron’s view the only way for coachbuilders to survive was by producing series of special bodies. This meant to be able to produce them in sufficient quantities to allow investing in semi-industrial manufacturing processes.

Using presses instead of rollers, for instance. To be successful in this segment one needed the cooperation of the manufacturers who mass-produced motorcars and had the commercial networks to sell such cars. Even before the war it had become a practice to source out work to subcontractors, just like in the building industry. In the past many founders of coach building enterprises had designed the bodies themselves and a few still did. But at the present time none of the larger French carrossiers employed an in-house designer/draftsman; everyone worked with free-lancers. Like Franay and Chapron themselves, most of them commissioned their designs from Carlo Déclassé and/or Philippe Charbonneaux.

Both Franay and Chapron were very honest with me but hardly encouraging.

At the Press day of the Motor Show I also met Herman Levy, the editor in chief of De Auto, the official publication of the Royal Dutch Automobile club KNAC. After I told him what I was doing in Paris and he had seen my portfolio he kindly proposed to me that I should write articles for his magazine with my drawings as illustrations. But stubborn as I was, I insisted that I first wanted to see the various coachbuilders, show them my work and try to find a job with them.

Saoutchik

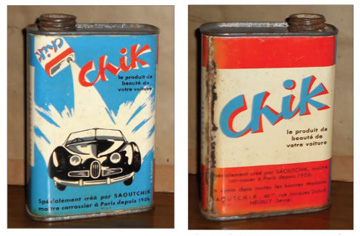

During my stay in Paris I made an appointment with Saoutchik at 46 Rue Jacques Dulud in Neuilly. I had the introduction from John Sijthoff, and I had always greatly admired the style and workmanship of Saoutchik’s creations, especially his pre-war ones. The visit went more or less as Peter Larsen describes in his book “Jacques Saoutchik, Maiter Carrossier”. I was received by Pierre Saoutchik, the son and managing director. He was friendly but hardly interested in my drawings and models. Instead he immediately asked me what I thought of the designs on two small tins obviously containing a car polish or wax.

These two different samples with a drawing of a gleaming car and in large letters ‘Chik’ and in a smaller cast ‘Saoutchik’. He told me that he intended to launch this product on the market and added, “Nowadays most car owners drive themselves. Only very few still have a chauffeur to wash and maintain their cars as was common before the war. And a great number of cars remain in the street at night instead of in a garage. I have asked around and I am convinced that we can sell this high quality polish. It is easy to apply, restores the gloss of the paintwork and protects it at the same time. By presenting the product as ‘Chik’ we hope to profit from the well-known name and excellent reputation of our coach building house Saoutchik.”

Before I could reply to his question Monsieur Jacques Saoutchik himself entered the room. He must have been in his early seventies by then. From the way he looked at the sample tins I could sense that father and son did not see eye to eve about marketing the car care products. Saoutchik senior carefully examined my drawings and scale models. Then he sighed and said. “Je regrette jeune homme: We don’t need a designer; we need welders.” When I replied that I had some experience with acetylene-gas welding and electric arc welding, he asked me to follow him to the workshop. He called the foreman, who handed me a thick leather apron, gloves, rod holder attached to the thick electric cable of the welding outfit and fitted with a welding electrode and a face mask. He also showed me two thin sheets of steel on a workbench. Saoutchik indicated that I should prove now that I could weld them together.

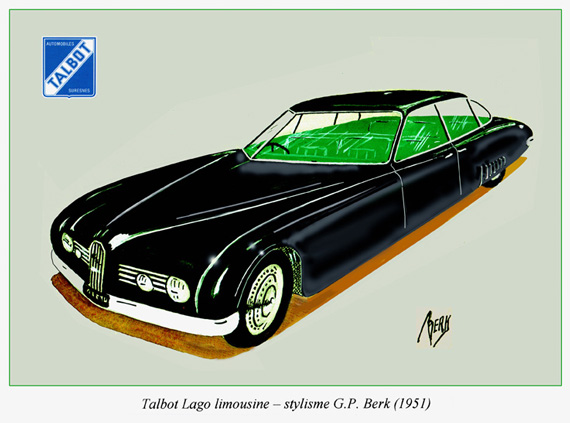

Design for a Lago-Talbot Limosine.jpg In the early nineteen fifties the 4.5 liter six cylinder Lago-Talbot Record could be bought with a four- door factory saloon body. But that was quite similar to two-door Coach Profilé and offered the same, rather limited, interior space. Both were built on identical chassis with a wheelbase (3.200 mm /126.0 in). However, up till 1940 Talbot also sold a long wheelbase (3.450 mm / 135.8 in) chassis. This would have been ideal for a roomy and luxurious limousine, which could compete with the newly introduced Jaguar MK VII. Hence my design.

I must admit to being nervous because all this was quite unexpected. But I managed to lay a nice narrow, regular and straight ribbon of electrode that united the two steel panels. Then Saoutchik told me I could work for him as an apprentice welder but because I was a foreigner without a working permit he was not allowed to pay me.

Naively I agreed, believing that if I had a foot in the door, this could lead to a full time job. The next day I started working on the left side front mudguard of what I believe was a Pegaso, the Spanish sports car make for which Saoutchik had become the French representative.

Asking the wrong question

But within a week I was fired. This was entirely my own fault. I had approached Monsieur Saoutchik while he came in the workshop and asked him why he continued using heavy wooden body and door frames instead of switching over to lightweight metal structures, like Touring in Milan and other Italian coachbuilders had done. Saoutchik never gave me an answer but turned around and walked away without a word. Within an hour the foreman told me that he did not want me to come back again. My behavior was of course extremely thoughtless and foolish, for two reasons. Most French companies in those postwar years were still very conservative and hierarchic; Saoutchik’s was no exception. Employees were not supposed to speak to their boss unless asked to do so. The second was that Jacques Saoutchik had been formed as a furniture- and cabinetmaker; wood was his favorite material. But I did not know this at that time.

Looking in a new direction

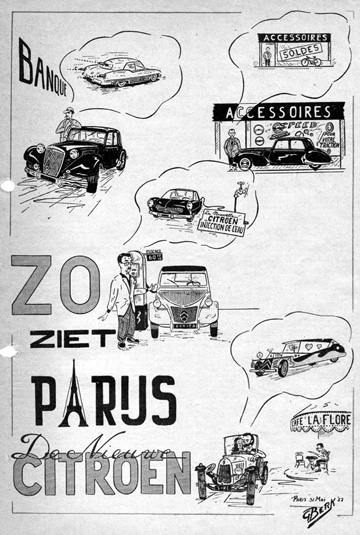

In 1952 the French weekly ’l’Autojornal ‘ published spy photos of a camouflaged prototype and a detailed description of what they claimed was to become the successor of the Citroën Traction Avant. The management of the French manufacturer was furious and started juridical actions against its publisher and its editorial staff. The French police even searched their offices to try to find incriminating material. My editor in The Hague asked me for more detailed information. Because the photos in ’l’Autojornal ‘ were not very useful, I drew up this cartoon showing what various French people expected of this new Citroën model and De Auto published it. Five years later, in 1955 the car would be introduced under the name Citroën DS.

It was a well-meant and sound advice and I remembered the proposition of Herman Levy at the Royal Dutch Automobile Club. I immediately wrote him that I would gladly work for his magazine. I thus became a free-lance contributor for ‘De Auto’.

Few people will remember it, but 1953 marked the beginning of what would become known as the Cold war. It started with demonstrations and strikes in East Berlin in protest against their Communist regime and the Soviet army intervened. This led to fears that Russian troops would invade Western Germany and the Low Countries. The Dutch government thereupon announced a plan to requisition private cars for military maneuvers. My stepfather was very worried that his MG would be taken away. For this reason I made this cartoon for him. In the end nothing happened in Western Europe, thanks to the clear warnings to Russia by the American government.

After all, at the end of my short apprenticeship with Gatso, Maurice Gatsonides, then facing bankruptcy, had taught me the importance of being ‘adaptable’. He had adapted his life from that of a small garage owner and unsuccessful sports car builder into that of a successful professional rally driver. It was a lesson I never forgot.

Besides I had to pay the rent for my small ‘chambre de bonne’ in the attic of an apartment building at the Place Adolph Max near Pigale.

Becoming a journalist

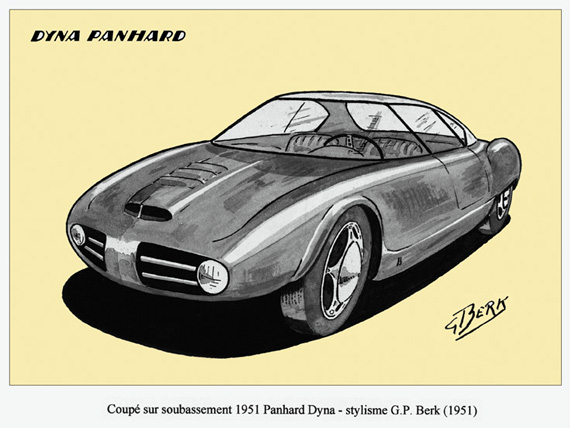

The lightweight chassis platform of the front-wheel drive Panhard Dyna X, with its flat-twin engine could in my opinion also be used for an attractive small two-door sports car or coupé. Around 1950 several French coachbuilders and tuning specialist had the same idea, among them Charles Bonnet of Deutch-Bonnet and Pierre Bourdereau of Monopole. This drawing shows my own concept: a roadster with a panoramic windscreen and a detachable hardtop. In 1952 Panhard introduced their own sports roadster, the Dyna Junior.

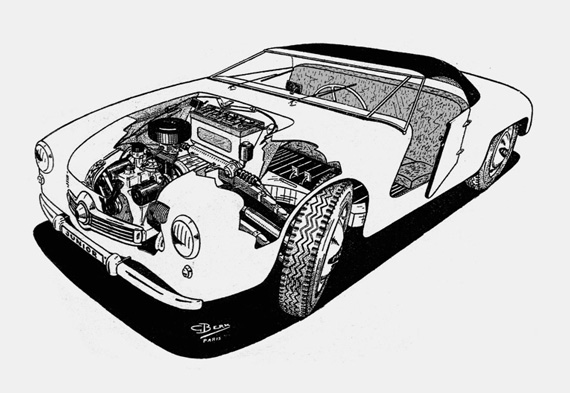

My new chosen occupation as a journalist/reporter brought me among other things in contact with the Panhard et Levassor company, who had just introduced the Panhard Junior, based on their twin cylinder Dyna. They allowed me to drive and study their car and it was the first of my articles ‘De Auto’ published. It was illustrated with a cut away drawing from my hand. Many other illustrated stories followed.

Panhard Junior cut-away drawing.jpg My first article for the Dutch magazine ‘De Auto’ was a description and road impression of the recently introduced Panhard Junior. To illustrate the story I made this cutaway drawing, using a factory photo of the engine mounted in the chassis. The commercial manager at Panhard (they did not have a Press service) was quite impressed. The Editor in Chief at the Royal Dutch Automobile Club liked it as well and published it.

At the Royal Automobile Club they must have been content with my work because when I went there during the Christmas holydays they offered me a permanent job. There was a vacancy in the Sports department and I could supplement my salary with continuing writing my articles for ‘De Auto’ which would be paid on a free-lance base. I accepted that proposition and never regretted it.

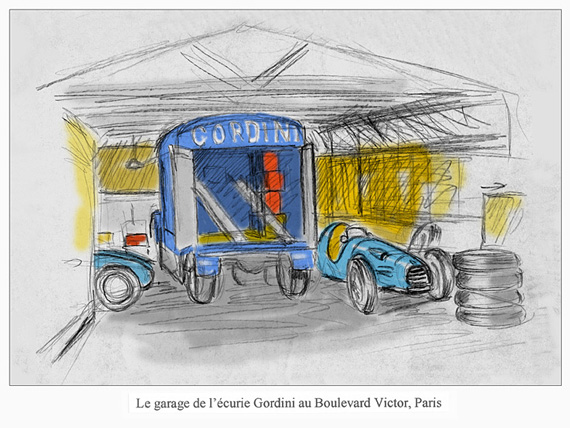

A sketch I made of the garage of Amedée Gordini while visiting him at his headquarters at the Boulevard Victor in Paris in 1956. At that time he had his workshop and garage nearly opposite the Exposition Center of the Porte de Versailles. The building does not exist anymore. Now there is a hotel.

My responsibilities as assistant at the Sports department consisted of helping regional motor clubs that wanted to organize sporting events with obtaining the necessary permits from the authorities and providing Dutchmen who wanted to participate in international rally’s and races with Competitor licenses. I also became closely involved in the organization of National rallys, and sports car races and the Dutch Grand Prix at the Zandvoort circuit.

Cars were not my only favored subjects. I always liked to draw animals as well. This is a sketch of one of our Corgis. We had three of them and they were all lovely companions

They paved the way for future changes in my career. Cars continued to play an important role in my life, but I always tried to remain ‘adaptable’.