Part I covered the Merosi cars designed from the beginning of ALFA in 1910 to the introduction of the RL in 1921, which would be the mainstay of the company until production of the Jano-designed 6C 1500 was underway in 1927. Part II features the details of the RLS, RLSS and the RLTF cars.

For 1926 several improvements were made as the RLN became the RLT (for Touring) and the RLS became the RLSS (Super Sports) The latter had dry sump lubrication, while the RLT now also had an engine capacity of 2994cc (and in the UK became known as the 22/70); power improved to 61bhp at 3200rpm, while the RLSS now revved to 3600 and produced 83bhp providing a maximum speed of just over 80mph.

A Castagna bodied RLSS built for an Indian Maharaja in 1921, shown at Villa d’Este. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

In February 1927 The Motor tested an example of the 22/90 hp Super Sports Alfa Romeo (presumably an RLSS) and gave the car a glowing report. The magazine pointed out that by 1927, although still a young company, the marque had already enjoyed tremendous success in Grand Prix racing courtesy of the P2, and also won the 1923 Targa Florio with an RLTF. The 22/90, which was related to the Targa winner, possessed fine performance and exceptional road-holding. The chassis was “a splendid example of clean design,” and “Several miles of traffic driving brought out the fact that the Alfa Romeo, despite its almost racing-car attributes, was remarkably easy to handle”. The magazine concluded that “the Alfa Romeo was an exceptionally fine production, beautifully finished, and a thoroughbred in its class.”

Thankfully for today’s Alfa Romeo enthusiasts, the RL series also proved popular with the better-off car buyer of the Twenties and approximately 2500 were produced between 1922 and 1927, making an interesting comparison with the 1600 examples of its famous British contemporary the Bentley Three Liter, produced over a similar period. It’s probably not over-stating the case to say that the RL range’s success ensured the survival of the marque.

In 1923, the RM model was introduced at the Paris Motor Show. This was essentially a four cylinder version of the six cylinder RL and the capacity was only about 40 hp. There was also a RM Sport, but production ceased after 500 cars of all types were made.

Ugo Sivocci behind the wheel of a RL Sports shortly before his death in 1923. Photo courtesy Alfa Romeo Museum.

Both the RLS and RLSS were considered high-performance cars with competition potential and works drivers such as Giuseppe Campari, Ugo Sivocci, and a certain Enzo Ferrari, gained some fine results alongside the efforts of several privateer entrants including the German Alfa Romeo agent, Willy Cleer, who took third place in the 1926 German Grand Prix at Avus behind Rudolf Caracciola’s victorious Grand Prix Mercedes.

However the modified road cars were never expected to be top level competitors and the company’s competition department was prepared to step up a gear with a series of special racing cars built in 1923 to compete in the Targa Florio road race around Sicily. These machines became know as the RLTFs and although the model’s competition career was relatively short, they built on the success of the earlier Merosi designs that had gained a fine reputation in Italian events both before and just after the war.

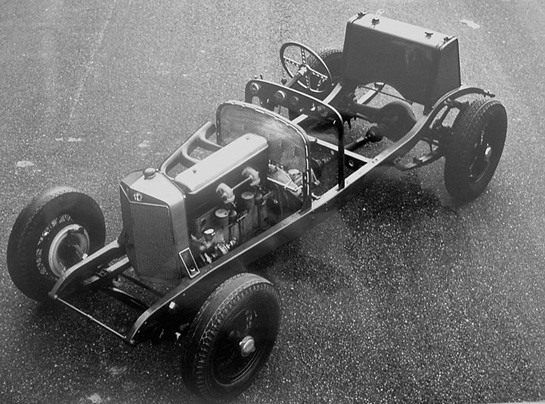

The RLTF chassis of 1924. The chassis was a foot shorter than that of the RLSS, it was much lighter, produced around 125 hp. One finished second in the 1924 Targa Florio. Photo courtesy Alfa Romeo Museum.

The respected Alfa Romeo historian, the late Peter Hull, believed that a strong case could be made for a prototype of the RLTF being entered in the 1922 250 miles Autumn Grand Prix at Monza driven by Sivocci. That car’s performance, against competition that included at least one 2 liter supercharged Grand Prix car, was exceptional with Sivocci finishing second in the three liter class behind a Grand Prix Diatto driven by Alfieri Maserati.

Whatever the truth of that, when the official RLTF first appeared it was smaller, had a lighter chassis and more power than the production series RL cars. The chassis had a wheelbase of 9’ 3” (2840mm), and was narrower, although the rear springs were moved outboard to compensate. The racing cars weighed between 19.5 and 20 cwt (1000 kg), compared with well over 30 cwt (1500 kg) for the production cars. For 1923 the cars ran with cowled radiators, and usually with a sharply cut-off tail, comprising the 22 gallon (100 liter) fuel tank with the spare wheel lashed on behind, although on one occasion at least a more streamlined tail was fitted to one example.

Of the cars built for the 1923 season, 3 retained the 2994cc four main bearings engine, but fitted with lighter valve gear and with the compression raised to 6:1 they produced 88bhp @ 3600rpm. Two more cars were built with a larger bore, taking the capacity to 3154cc. They produced 95bhp at 3800rpm, and had a maximum speed that nudged 100mph. Like the RLSS, the racing cars all had dry sump lubrication.

It was with one of the larger-engined machines that Ugo Sivocci presented Alfa Romeo with the company’s first International victory in the 1923 Targa Florio, taking just over seven hours to complete the course, with Antonio Ascari finishing second in one of the three liter models.

The same year Ascari also won a race at Cremona while Count Masetti won at Mugello, then made the fastest time in the 3-liter class at two important hill climbs, the Coppa della Consuma and on Mont Cenis. Enzo Ferrari won the Circuit of Savoia held outside Ravenna in one of the three liter cars, and began to build a legend. Amongst the spectators were the parents of the Italian World War One flying ace, Francesco Baracca. Impressed with Ferrari’s performance, they presented the winner with their son’s emblem — a shield depicting a black prancing horse set against a yellow background — a badge that would become forever associated with the Ferrari name.

Following the successes of 1923, for the following season the cars were modified with a vee-shaped radiator similar to that of the sporting RLS/RLSS road cars, but the racing cars kept the same ‘cut-off’ style of bodywork with twin spare-wheels strapped behind a larger 33 gallon (150 liter) fuel tank. The engines were developed over the winter months and now had a seven bearing crankshaft. Three of the cars retained the 2994cc engines, now producing 90bhp at 3600rpm, but the other two now had an increased capacity of 3620cc. These produced 125bhp at 3800rpm and gave the cars a maximum speed of over 110mph.

An Alfa Romeo RLTF at a recent British car show. One RLTF has been in the U.K. since 1925, bought by Fred Stiles when in Milan while arranging the British franchise for Alfa in 1924. It was chassis TF 11, believed to have been driven by Campari in the 1923 Targa Florio. Photo by Simon Wright.

The competition department was also busy building the first of Vittorio Jano’s P2 Grand Prix cars but the Targa Florio — always important in Italy — required a well-proven design and come April the Portello works entered a strong team of Ascari, Campari, Masetti, and French veteran Louis Wagner, in the revised RLTFs. The team faced serious opposition from Mercedes, Peugeot and Fiat but the rising star, Antonio Ascari, managed to take a lead of a minute into the final lap. Unfortunately for the defending champions the RLTF’s engine seized almost within sight of the finishing line. Ascari’s mechanic, Giulio Ramponi, struggled to restart the engine but had no joy so the pair attempted to push the Alfa home.

With help from officials and spectators the car was pushed over the line with a time still good enough for second place to Christian Werner’s Mercedes, but unsurprisingly the car was disqualified. Meanwhile Masetti managed to salvage something for the team by coming home in second place in one of the 3.6 liter cars.

The works team’s attention now turned to Grand Prix racing with the P2, but Enzo Ferrari used one of the 3.6liter RLTFs to win the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara, and the following year a privateer, Guido Ginaldi, won the same event and was also placed second in the 1925 Rome Grand Prix behind a Bugatti driven by the former Alfisti, Count Masetti.

The RLTFs were now dispersed around the world — at least one went to South America, a popular destination for obsolete Italian racing machinery — whilst another turned up in England where it appeared at Brooklands, driven with some success by Augustino Lanfranchi in the typical short handicap races around the fast banked circuit that were very different from the traditional Italian road races for which the model was developed.

By 1927 the works team had put the RLTF well behind them, but for the first running of the legendary Mille Miglia — an heroic thousand mile road-race from Brescia to Rome and back — the factory entered two examples of the RLSS; one driven by Count Brilli-Peri with Carlo Presenti, the second by factory test drivers Attillio Marinoni and Ramponi. Unfortunately both cars retired from the race, but the following year Ramponi sat alongside Campari as the burly Grand Prix driver took Alfa Romeo’s first Mille Miglia victory on one of Jano’s jewel-like 6c1500 sports cars. By now the Merosi period was over, but with the RL series the Milan manufacturer had paved the way for the great years that lay ahead.

The statement in the article “a shield depicting a black prancing horse set against a yellow background” is not exactly true. The shield was originally black (horse) on white. Enzo Ferrari changed the colour to yellow because yellow was the colour of his homecity Modena.

The Alfa Romeo RLSS featured above was actually owned by my Uncle in the sixties,he has a picture of him sitting in it when he was in Lahore in 1964 before selling it ,I am hoping to visit the museum and am looking forward to seeing my Uncles pride and joy in 2017