Reveiw by Pete Vack

Images from the book unless otherwise noted

David Beare first introduced himself with the publication of Panhard, the Flat Twin cars 1945-1967 and their origins in 2013, which we thoroughly enjoyed. His books, then and now, are enthusiasts publications; softback, low price, chock full of technical information and historical information. Our kind of book.

After the success of the Panhard book, Beare decided he wanted to write a book on Pegaso but found that it was almost impossible to do so unless he researched the creation of another car, the Hispano-Suiza, and Spanish social and political history. What began as a single slim volume on Pegaso became a larger two volume work that incorporates not only an overview of Hispano Suiza, but Marc Birkigt and the often sad and violent history of the Iberian peninsula.

Beare almost apologizes for his inclusion of Spanish history. “You can choose to read it or not, depending on how much you enjoy history!”, he wrote. But in short order you will probably agree that learning something about the history of Spain from the 15th century to the Spanish Civil War is not only necessary, but a good read. It certainly makes one appreciate what Hispano-Suiza, Marc Birkigt, ENASA and Wifredo Ricart were able to accomplish in the face of almost unsurmountable obstacles.

Volume One, Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso Birkigt & Ricart: Two men, two marques made in Spain was published in 2016; Volume Two, Pegaso and Ricart: From Hispano-Suiza to Pegaso: Trucks, busses and a sportscar and was published in 2017. We’ll review each in order.

L’Homme á L’Hispano, written by Pierre Frondaie was a best seller about a man, a Hispano-Suiza and a tragic love affair in the 1920s, and was made into two movies. This poster depicts the Jean Epstein 1933 version.

The first volume explores in detail “… the Spanish Hispano-Suiza company’s formation, tribulations and designs for automobiles and truck and aero-engines…” writes Beare. He takes a good look at the products of the Barcelona and Madrid factories while not overlooking the more famous line of cars produced in Paris. But this is no simply car history; as the history of Hispano is well told elsewhere, Beare fills the pages with interesting almost tangential material from other Spanish marques to asides about the Roaring Twenties and movies featuring Hispano cars.

While some may offer that there is perhaps too much detail about the three-year Spanish Civil War, it defined the stage that would bring the end of Hispano-Suiza and the beginning of ENASA, (Empresa Nacional de Autocamiones S.A.) which in turn gave birth to the Pegaso sports car. It was also the end of the brilliant Marc Birkigt’s role as chief engineer for Hispano, and the beginning of a new career for Ricart.

Posters were great propaganda for both sides during the Civil War. This one says “Long live the great victory in the war against communism! Long live Franco!”(And did he!)

Beare recounts a particularly complex era…roughly 60 years of war, violence, revolution, depression and anarchy and dictatorship that was Spain between 1900 and 1960. The Civil War, won eventually by the conservative powers of the Military Falange and headed by Franco, brought some stability to the country as Franco governed as a dictator until his death in 1975. But it was not a great environment for business, as many were nationalized and became part of the government bureaucracy. That Hispano-Suiza not only survived (until WWII) and often profited was no mean achievement abetted by good products and military orders for trucks, aeroplane engines and machine guns. Writing about this era is a huge task, and Beare has done a great job in encapsulating what is necessary and keeping focused on his goal.

A truly delightful book written by an enthusiast for enthusiasts. We devoured it.

En-route, Beare tells us fascinating stories. He describes the early years of Hispano-Suiza and explains the role of King Alfonso XIII played in the company; Alfonso was not a mere footnote but a significant supporter of Hispano-Suiza. Not only was Hispano’s first sports car (and perhaps the world’s first sports car) named for the King (read Alfonso Car and King) but so was Birkigt’s first overhead cam car, which was given the name ”Tipo España” reportedly by Alfonso himself. The new single cam operated two valves set at an angle, creating a penthouse like combustion chamber. For many years it was thought that this design—or perhaps a DOHC drawing based on the SOHC design, was taken by Hispano race driver Paulo Zuccarelli and given to Ernest Henri which resulted in the famous GP Peugeot DOHC engine. But no proof, only speculation, and nowhere in his research did Beare uncover any DOHC engine designed by Birkigt. “I’ve never found sufficient concrete evidence to suggest Birkigt designed or made a DOHC 4-valve hemi-head engine for Hispano-Suiza. Those guys were constantly sketching new ideas on the back of envelopes, pieces of scrap paper, on the back of old drawings, and Birkigt may have indeed sketched something like the Peugeot engine layout (who knows- it might have been ideas for an aero-engine) then slung it in the bin as too complicated to manufacture with 1910-11 technologies, only to be retrieved by Zuccarelli or someone else?”

In the meantime, Hispano-Suiza Barcelona was doing great business, manufacturing busses and trucks for a country emerging from the middle ages. Sales of chassis increased particularly in France, and therefore Hispano Suiza established another factory in Paris. Swiss-born Birkigt loved the idea and would thereafter spend a great deal of time at the Parisian factory.

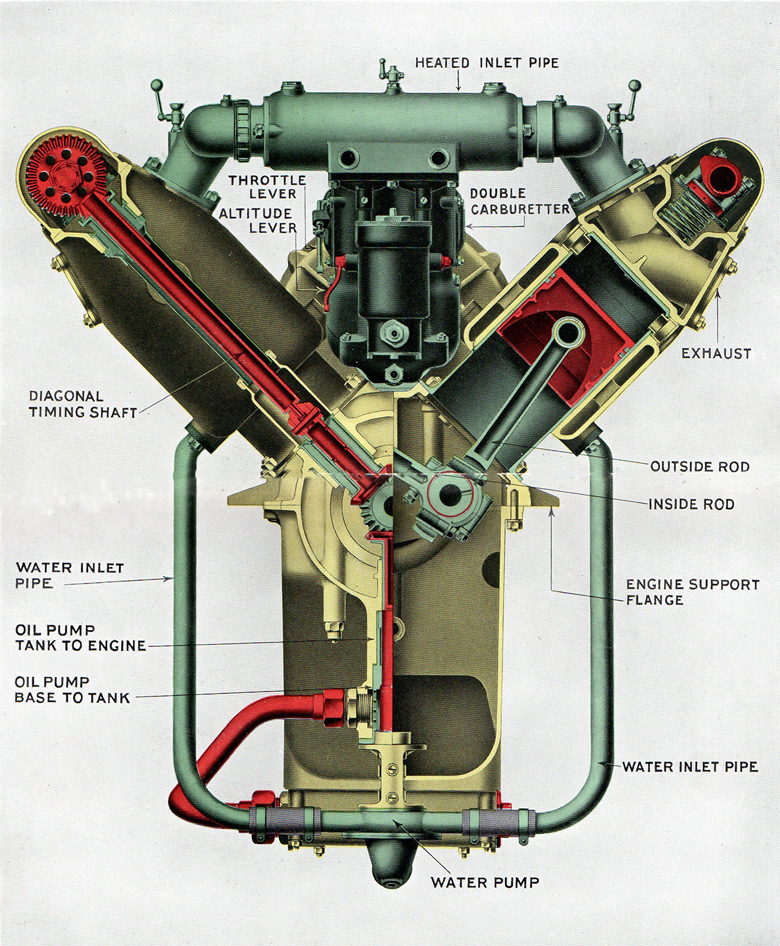

One of the licensees for the Birkigt V8 aero engine was Wolseley, who made significant improvements to the design. They also produced a color instruction manual for aircraft fitters, this being one page of same.

Only a side bar for us but Beare is obviously up on his military equipment as he gives us a chapter on the Hispano-Suiza V-8, one of the most successful aero engines of all time. Interesting that the factory in Barcelona which initially designed and developed the engine produced only a few hundred; the rest of the almost fifty thousand engines were built under licence by Hispano in France, Wright in the U.S., and Wolseley in the U.K.

After the war the surplus aero engines were put in race cars, a notable one being the Delage-Bequet which is still in use today at Vintage meets. (Read Driving the Big Ones.)

Another delightful side excursion was the saga of the Micheline, a combined effort of Michelin and Hispano-Suiza to create a quiet and fast alternative to the steam engine. Beginning in the mid-1920s Michelin and Renault experimented with a series of rubber-tired railcars and by 1931, Michelin was working with Hispano, who provided a modified H6 chassis and engine and a lightweight carriage compartment. It bested the luxury express steam train from Paris to Deauville by 32 minutes. The Micheline concept was continually upgraded and in use for many years; later models were often powered by V12 Hispano-Suiza engines. Beare reports that a Micheline with a Hispano V12 was discovered in 1999 in China, in pretty wretched condition. But the Michelin tires still had air.

Sidetracked but in a vey interesting manner. The story of the French railcars did not belong solely to Bugatti, but both Renault and Hispano were involved in the developement of fast, small railcars powered by automotive engines with rubber tires. Here the Hispano-Suiza version that set records between Paris and Deauville.

Throughout the twenties, the Hispano H6 series (SOHC, six cylinder, up to 8 liters) were the swells of the automotive world, but Birkigt knew that he must keep up with the times. His new V12 gave up the long stroke used in the past for an almost square dimension of 100 mm bore and stroke. He also used pushrods instead of the gear driven OHC, as they were much quieter. Launched in 1931, it was perhaps Birkigt’s greatest automotive moment. It all came to naught after 1936 when the firm was redirected by the French government to manufacture armaments and aero engines rather than cars.

Birkigt, never anyone’s fool, had left Barcelona for Paris after the establishment of the new branch, saw what was coming in 1939, designed a remarkably effective and versatile 20 mm cannon, made a fortune on the patent, and went off to live in his homeland until he died in 1953 at the age of 75.

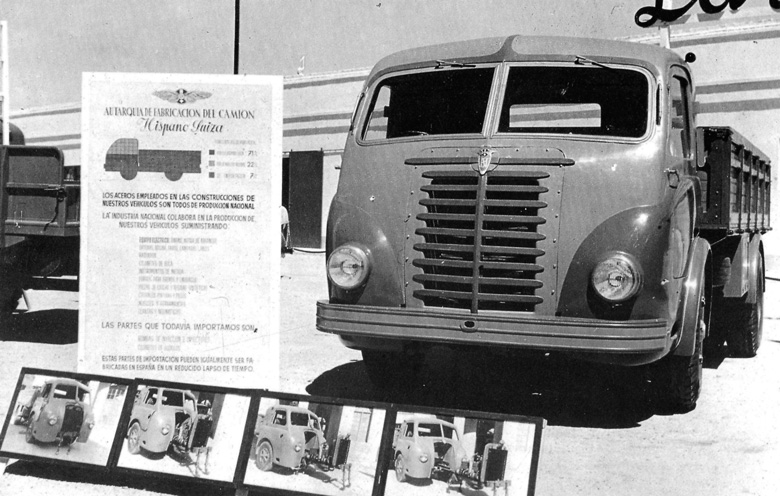

Hispano in Barcelona and Madrid continued to make a successful line up of trucks throughout the war years, but Franco and friends had other ideas, a new project involving the national organization to manufacture trucks and cars in Spain called CETA (Centro de Estudios Technicos de Automocion) under which was ENASA.

Almost always successful at building trucks, in 1944 the Hispano 66G was introduced. The entire drive train could be disconnected and rolled out on rails for repair. It was also the last Spanish Hispano-Suiza production vehicle designed and built in Barcelona. It would become a product of Pegaso in 1946.

But wasn’t that already what Hispano Suiza was doing, and quite successfully? Oops, too bad. As ENASA had no factory or workforce, the government simply forced Hispano Suiza to sell out everything to ENASA, and an ex-Alfa Romeo engineer originally from Barcelona, Wifredo Ricart, was offered a free hand in creating the new organization.

And that is how Hispano Suiza become Pegaso, and the engineering baton passed from Birkigt to Ricart.

Beare has included source citations in the text of his work, included a bibliography but unfortunately no index.

Books can be ordered from David Beare’s website, wwww.stinkwheel.co.uk using a credit card, PayPal or by post.

Next up: We review Volume two, Pegaso and Ricart.

This is brilliant and something I have been looking forward to for many decades. Pegasso is one of the saddest unsung heroes stories of that era. There is very little on it but putting the history of Spain into the story is genius. can’t wait to read it.

Great!!!!! Jaime I