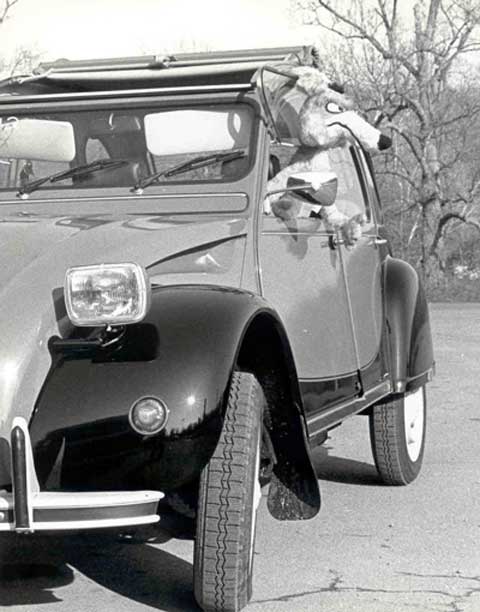

Photo by Mary Decker Vack.

Pete Vack on the Immortal Deux Chevaux

Deux Chevaux, Deux, meaning two, and Chevaux, (Cheval Vapeur, or steam horse) a terms which means horsepower and was the the basis for a sliding scale of ratings for taxation purposes.

The Citroën 2CV was one of France’s most popular cars and was in continuous production from 1948 to 199. It was iconic, but not the result of Andre Citroën’s vision–he died in 1935 just as the planning for the 2CV was started.

The Deux Chevaux was the brainchild of an ex-Air Force captain by the name of Pierre Boulanger, a man who knew what he wanted. Boulanger gave Citroën chief engineer Maurice Brogile some very specific and unusual parameters. He requested Broglie to design a French Model T, big enough to carry two farmers in their work clothes and 110 pounds of potatoes, high enough to ride over the most primitive roads, have a maximum speed of at least 37 mph, and hopefully manage around 90 mpg. Broglie called upon the young Italian Flaminio Bertoni (not to be confused with Italy’s Nuccio Bertone) to help style the French T.

Citroën 2CV prototype TPV 1939. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

Work began in 1935 and by 1937 a BMW motorcycle-engined prototype was ready. It incorporated an interacting torsion bar suspension, a hydraulic anti-dive system, and an all-aluminum chassis spot welded together. None of these features made it into production, but slowed the development considerably.

Neither the war nor the slow development dampened Boulanger’s spirit, and the new post war economy hastened work on the 2CV, which was still a rough prototype. Walter Becchia, a recent recruit from Talbot, suggested an air cooled 375cc flat twin engine, eliminating a cumbersome water cooled unit previously considered. Becchia’s engine measured 62mm by 62 mm and produced a real 9 hp at 3500 rpm, and was attached to an all-syncro four speed transmission with a single plate dry clutch.

A decision to use steel instead of aluminum floor plans increased weight but decreased cost and trouble. An interacting suspension was still desired, but instead the design used enclosed compression coil springs placed parallel to the chassis and actuated by trailing arms and rods. It is a method that defies a clear description and yet works reasonably well. Oscillations were controlled by inertia weight dampers in a canister located inside of each wheel, augmented by a friction damper at the trailing and leading arm pivot. Brakes were hydraulic drums, inboard at the front, and rack and pinion steering was another advanced feature.

Amazingly, the addition of disc brakes up front and tubular hydraulic shock absorbers and increased engine displacement were the only fundamental changes to the chassis of the 2CV throughout its life.

Boulanger’s dream, though not precisely what the captain had ordered, was ready for the public by the 1948 Paris Auto Show. The demand was overwhelming and the little car generated a waiting list that did not dwindle for years to come.

Variations

Citroën 2CV Sahara. Photo by Romain Moormann.

With the success of the 2CV came variations of the car designed for commercial and military uses. In an effort to modernize the 2CV, the Ami range was created in 1961 and later the Dyane, which was introduced to fill a gap between the 2CV and the Ami. Neither captured the public’s devotion but did offer more luxurious alternatives.

Citroën Mehari. Photo by Romain Moormann.

As a military experiment, Citroën’s engineers came up with a twin engined, four wheel drive 2CV called the Sahara, but only 694 were built. The Mehari was a more successful version, a little like the BMC Mini Moke, it was based on the Dyane platform and used an ABS thermoplastic body.

Citroën 2CV Charleston 1990. Photo by Alessandro Gerelli.

Citroën continued to make small improvements to the 2CV, and by 1970 the displacement was up to 602cc and 33 hp, and a 12 volt electrical system replaced the 6 volt system. Limited edition models became popular, such as the James Bond “For Your Eyes Only” 007 model, all painted yellow with bullet hole decals on the trunklid. Another model, called the Charleston, offered special paint and a luxurious interior.

Driving a 2CV

Photo by Mary Decker Vack.

During the mid 1980s, a number of 2CVs were imported into the U.S. To get around the DOT EPA regs, they were not new, but totally rebuilt 1967 or earlier models. These were created by a dealer in Belgium who installed new engines, drivetrains and interiors, complete with special paint ala the Charleston.

Driving a 2CV is an experience. Sorting out the gearshift and accepting the lacksidaisical acceleration takes some getting used to. The shift lever protrudes from the dash and the pattern is non standard, but like a Ferrari, with first down at the left and second where first normally is. Finding second took time as the engine revved, beyond its redline no doubt, but we were soon mobile. Steering effort was heavy (early front wheel drive engineering) and the brakes seemed heavy but adequate (by this time they had discs up front).

We found the horn button while shifting (press right lever in) opposite the turn signal, and noted the reasonably complete instruments easily visible through the DS-like one spoke steering wheel. A warning decal in four languages reminded the driver to check and add oil, and another indicating the shift pattern.

The engine runs smoothly yet with a strange beat making it hard to forget that it is just a two lunger. Noise is fairly high and the model we drove didn’t bother to have a radio.

Through the countryside on rural roads, the Citroën felt very much at home, and buzzed happily over hill and dale, performing well unless asked to do something outside the envelope, like corner hard. A handler it is not, endowed with terminal understeer and a Mount Everest roll center. It was, at times, alarming as we cranked and tilted around exit ramps.

Photo by Mary Decker Vack.

We noted the fresh air vents directly under the windshield that were simply screens covering holes in the body–great for bean counters but not nice when raining. The half windows are either up or down, and somewhere between the two they merrily flap in the breeze. Any attempt to latch them while in motion was frustrated due to a lack of any handle on the frame. Rolling back the roof–much more than a mere sunroof–reminded us of opening a tin of sardines. But there was little wind noise or turbulence once the 2CV became a semi-convertible.

The 2CV is a car which must be taken as is, with all of its foibles, faults and lack of features, its outrageous appearance which never fails to attract amused attention, and it implicit honesty, which can never be questioned. It became something that even in their most imaginative moments (and there must have been plenty) its creators could not have dreamed —a symbol of chic, a toy for those who have money to burn and the confidence to drive something so distinctively different. Sort of a French Revolution in reverse.

We leave you with the ultimate in 2CVs, this against all odds race car, found and photographed in France by our correspondent Brandes Elitch.

A 2CV race car. Photo by Brandy Elitch.

the 1939 prototype – like the ford trimotor, clothed in corrugated sheet iron.

after 1944 known affectionately by all the GI’s in europe as the douche bowl.

i really hated those 3-bolt wheels, especially on the renaults.

i was told the last production 2cv rolled out of the portuguese factory in 1988.

> jack

I had one in the 80’s. I learn driving on it. Simply the first car I loved.

Brings back memories.

I learned to drive in my grandmothers 2CV on forest roads long before I was old enough.

I remember a unique feature of the transmission not mentioned in the article. You could engage 1st gear using the cluch and the let the clutch out without the car moving. The car would only go when you applied the gas, like a gocart.

I dont know how it worked and a quick web search did not help.

Dear Editor: I’ve learned to drive in my Mom’s ’73 Mehari, then I’ve owned an AK400 Furgonette (The cargo Van, then I graduated to a full 2CV (Wich for some obscure reason was called 3CV in Argentina. My last 2 cylinder Cigtroen was a ’79 Visa, built at the time that Citroen came under PSA. It was the chasis of the Peugeot 104 with the venerable 2 cyl. enlarged to 650 cc’s that made up to 125 Km/h. Loved that car, the best handling small car I’ve ever driven. Keep up the good work,

Carlos Madero

Chevy Chase, Maryland

Hello,

A memory that I will always cherish-

Back in 1978 my girlfriend and I quit our jobs and took a semester break from college. We embarked on a 2.5 month backpack trip through Europe.

I really wanted to visit the D-Day invasion site at Normandy Beach. Leaving Paris, We took the train as far as we could. There was no bus or train service to the invasion sites at that time. We fashioned a cardboard sign with “Caen” neatly printed on it with an American flag drawn on the same sign. After standing on the highway for about 10 minutes a 2CV, comes to a dusty halt, inside were 2 young French couples and a german shepard. They were happy to take us almost to Caen. We were all about the same age- in our early 20s. Our backpacks barely fit in the trunk as we shoe horned ourselves between the cute French girls and the german shepard. The 2CV lumbered off. We knew really no French, and they spoke some English. When the driver found out we were from the SF Bay Area, he asked us if we ever saw the Jefferson Airplane or The Grateful Dead, yes!

Off we went, weaving and laughing, trying to communicate and sandwiched between the two french girls and my girlfriend. It sounds almost too good to be true if it wasnt for that dogs butt being in my face.

That was my first and only real experience with the little 2cv.

David Martinez

Fremont, Ca

I shall never forget the hilarious movie, “Mr. Hulot’s Holiday”, in which the car was more the star than the actor who attempted to drive it. Oh, is there someone out there who remembers his name?

Handling and road holding were superb but not comparable with anything else, once you understood it you could throw it into a bend and it would lean like a motorbike but the wrong way, snow was no problem and you could drift it around on ice with precision. I had cruise control on mine, a brick you rested on the accelerator, very useful on motorways and it reminded you that the engine was unbreakable. I miss my snail.