As told to Robert Little, Renzo Carbonaro, Vladimir Pajevic and Ulrich Zensen

Copyright: 8 November 2017 All World Rights Reserved

Republished with permissions with changes to suit the format of VeloceToday.com

Part VIII: Near Crisis Creating the World’s Most Beautiful Automobile-the Alfa Romeo Stradale

From the moment of the first T-33 victory at the 1967 Fléron hillclimb in Belgium to support the growing success of Alfa Romeo racing cars on the circuits of the world, and to add contrast against other competing European “dream cars”, President Luraghi (CEO of Alfa Romeo S.p.A.) absolutely wanted to start small production of a high performance road car.

Jonathan Sharp’s dramatic shot of the Stradale,which was the star of the 2013 Goodwood Festival of Speed.

He appointed the volcanic personality Ing. Carlo Chiti to accomplish his desire, and Chiti in turn approached Franco Scaglione, the genial, sophisticated Tuscano car body designer, who Chiti knew to be the most talented car design artist in the world of automotive design at that time.

Chiti and Scaglione had collaborated as two fellow Tuscans on the ATS 2500 berlinetta. Scaglione had accepted the design commission while the assembly of the 12 ATS units were contracted to Carrozzeria Allemano.

Speaking of Scaglione, one must remember his impeccable sense of beautiful, artistic “design language”, his low tolerance for compromise and his driven fury to transform anything into a perfect artistic shape. Of noble origins, Scaglione was considered a kind of arbiter within his automobile design circles.

Observing Mr. Scaglione’s three preliminary drawings of the proposed T33 Stradale laid before him, Luraghi immediately chose just one of extraordinarily rare beauty and proclaimed, “Let us produce this one”.

The proposed car was an amazing design achievement for the day…or any day for that matter… and the initial proposal was to build 50 units based upon the winning “Fléron” chassis. Scaglione demanded and was granted full freedom in designing this dream car with the outcome resulting in an uncompromised layout of stunning proportion.

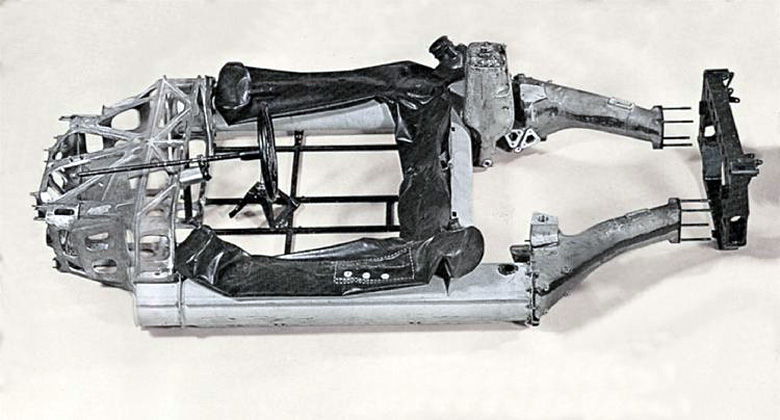

The Fléron chassis was a futuristic concept based on two large diameter riveted magnesium tubes, connected together with the same diameter-sized tubular cross member at the rear of the cockpit, forming an irregular H shape perimeter frame of the car.

Another peculiarity was its fuel tank situated inside those huge tubes that ensured the ‘roll center’ and perfect balance of the chassis would always be maintained…regardless of the remaining fuel volume.

For a discussion on the T33 chassis, click on this photo of the T33 Prototype by Roberto Motta

https://velocetoday.com/alfa-romeo-t332-chassis-001/ Note that Franco Scaglione was not responsible for the design of the prototype race cars.

The steering, double wishbone suspension and V-8 engine were mounted on magnesium-alloy subframes. The chassis was produced by a small aircraft factory “Aeronautica Sicula” located in Palermo (riveted magnesium tubes) and “Campagnolo” from Vicenza (front and rear subframe).

The “Stradale” road version featured a number of differences from the race version. The mainframe tubes of the road version were produced of steel, and the extended wheelbase (+10 cm) allowed substantially more cockpit space… while the two magnesium subframes were reinforced with steel to afford major impact protection.

Even in the road version, the chassis was not so different from the one used for racing…the difference being the racing version had some interior structural components fashioned in aluminum instead of steel.

The engine was slightly detuned for road use, with the redline set at 10,000 rpm. Compression was reduced to 10.0:1, yielding 230 bhp at 8,800 rpm with Italian SPICA fuel injection. The car followed Alfa Romeo President Luraghi’s edict that the road version specifications must not be inferior by more than 5% from its competition version. While everything else was conceived at extreme spartan levels, the cockpit was sufficiently comfortable and had its own slick, sexy racing appeal.

The major problem for the extremely low Scaglione design of the car (99 cm) was the difficulty in accessibility (getting in and out!). To resolve that inconvenience Franco Scaglione conceived and produced a vertical opening of the doors along with part of the roof. That solution gave an absolutely stunning appearance to this already exotic design.

Mouse Motors’ lovely Alfa Romeo Stradale won Best of Show at The Quail. Based on their Tipo 33 race car of the late 1960s, only 18 of these were built in two versions. This is the later version. Earlier cars had four headlights and did not have the front fender side vent. Power was a 2-liter V-8 like the racing cars. Photo by Michael T. Lynch

To fabricate the body Ing. Chiti and designer Scaglione adopted Peraluman H350 lightweight alloy, and it was mutually decided to build the first prototype car directly inside the Autodelta premises at Settimo Milanese. The working space was allocated in the same section of the building where racing engines were assembled.

Franco Scaglione enjoyed an excellent relationship with all of those around him. The shortage of experienced technicians capable of shaping Peraluman obliged Scaglione to accept the loan of skilled workers from Zagato, and to start traveling daily from his home in Torino to the Autodelta Settimo Milanese walled factory to supervise the building progress on the car.

Giovanna Scaglione recalls those days when her father was commuting from their home in Torino to Milano’s Stazione Centrale each morning. She shares with us a look into his daily life routine:

“Babbo, every day at 6 o’clock in the morning, took the train to reach Milano. At the station he found a worker who had to go from the station to the factory. So they loaded him into the car and went to work together. In the evening he took the train at 7 pm and returned home at 9 pm. We had time to dine together. All this lasted for more than a year and a half.

“He was a very cheerful and kind person, both at home and at work. Always determined to prevail over his reasons when designing a new car and always available to help workers to model the dress of the car. He used to spend a lot of time working in the workshop side by side with the workers. Everybody was pleased of his presence… especially when they were in a trouble with the rapid advancement of work. I can say that “Babbo” felt better by the workers side than with managers, with whom time to time he had big fights. At lunchtime, my Babbo always ate with the workers. There was no table and so they all brought something from home, including for my father. This might appear as strange, but he felt that’s alright.

“At home he was always very understanding. Even when he returned tired, he never neglected Mom and me. We always wanted a great deal. Sometimes there were discussions but never anything serious. For me he was a wonderful father. Thoughtful but very attentive to my education, making me understand where I was wrong and helping me to grow polite, helpful, he was able to understand the little problems of a child.

“And let me add…time to time we had a few arguments, but never important ones. For me, “Babbo” had always been a great dad. A thoughtful father, but teaching a good education; when I made mistakes he used to tell me what I made wrong and helped me to grow with good moral principles in order to face life without remorse.”

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

Read Part 5

Read Part 6

Read Part 7