Editor’s Note: This part of the Scaglione interview is very lengthy at 2500 words. However, we think that what is revealed here is of great interest and should be published at one time to encompass the entire story. We hope you will agree.

As told to Robert Little, Renzo Carbonaro, Vladimir Pajevic and Ulrich Zensen

Copyright: 8 November 2017 All World Rights Reserved

Republished with permissions with changes to suit the format of VeloceToday.com

Part IX: The Stradale Project Encounters Unforeseen Difficulties

Two geniuses rarely co-exist together comfortably, and sure enough problems arose between Ing. Chiti, immersed in his racing world, and Scaglione, compelled to resolve the growing technical and assembly problems by himself. That silent war was flavored with numerous embittered letters that Scaglione sent without effects to all pertinent addresses. Years later, Scaglione would describe his time at Settimo Milanese as “the worst period of his life.” However, with proverbial Tuscan obstinacy, he finished the first Stradale prototype in a relatively short time, from January to September 1967.

The finished product was proudly presented to the public at the occasion of the Sport Car Show in Monza. Some remaining testing was finished up just before the point of its official presentation at the Torino Automobile Show in November, 1967. The car shocked the public with its aggressive appearance, its sensual appeal, and its price, which was at the top of almost every automobile price list at the global level. Despite this, after the initial example was completed under the huge, expansive cathedral-like Autodelta ceiling, Scaglione left Settimo Milanese and Alfa Romeo forever.

Photographs of the Stradale often don’t do it justice. However, photographer Jonathan Sharp used the early morning light at Amelia in 2015 to catch the beauty of the Scaglione masterpiece. Photo by Jonathan Sharp.

Giovanna Scaglione recalls: “It is considered one of the most beautiful cars ever made. But before the 33 Stradale was able to see the flowers it was a real amazing event to behold behind the scenes, between my father’s daily verbal litigations with Ing. Carlo Chiti, difficult, exhausting and emotionally tiring working conditions, fifteen months of daily commuting from Torino to Milano and returning each night (over 350 km travelled each day, starting at the very early hours of the morning and returning to the very late evening) and compensation delivered with great delays. More than once my Babbo was on the verge of abandoning the enterprise.”

Alfa Romeo had presented a contract for him to review in October of 1966, and on the 29th day of December, 1966 he signed that contract making specific requests. Ing. Carlo Chiti countersigned the agreement on behalf of the corporation. The document was written in an abstract manner specifying the prototype, a single car, to be created ‘in situ’ in Autodelta workspace with all necessary requirements provided by Scaglione and under his direct control. There was no strict stipulation concerning the number of cars to be supervised by Scaglione under the terms of the contract.

It was Scaglione who later decided to satisfy President Luraghi’s desire to build a competition Stradale version. When those plans for a racing version were abandoned months later, Scaglione promised to finish the car at a convenient future date.

That particular car was to be eventually given the chassis number 105.33.12 and today rests in splendor at the Alfa Romeo Museo Storico in Arese, Italy.

Giovanna continues: “Requests were disregarded, unleashing the wrath of my Babbo. And it was utterly incomprehensible how the company’s leadership could think of taking on such a delicate and challenging job as creating a prototype in a workshop that had only a workbench with vise in poor condition, a portable arc welding, a welding cart and a sole welder to work with part-time.

“Requests by Babbo resulted in Autodelta subsequently dropping certain of its conditions so as not to trigger the anger of the Tuscan designer. In several cases, hours and hours were lost while waiting for Mr. Caffa to be free for a welding operation! There was not a pipe bending machine, not a sheet metal bending table, in fact less than you could find in a small repair shop! At first he had to only a single worker, then after more than a month, there arrived a second.”

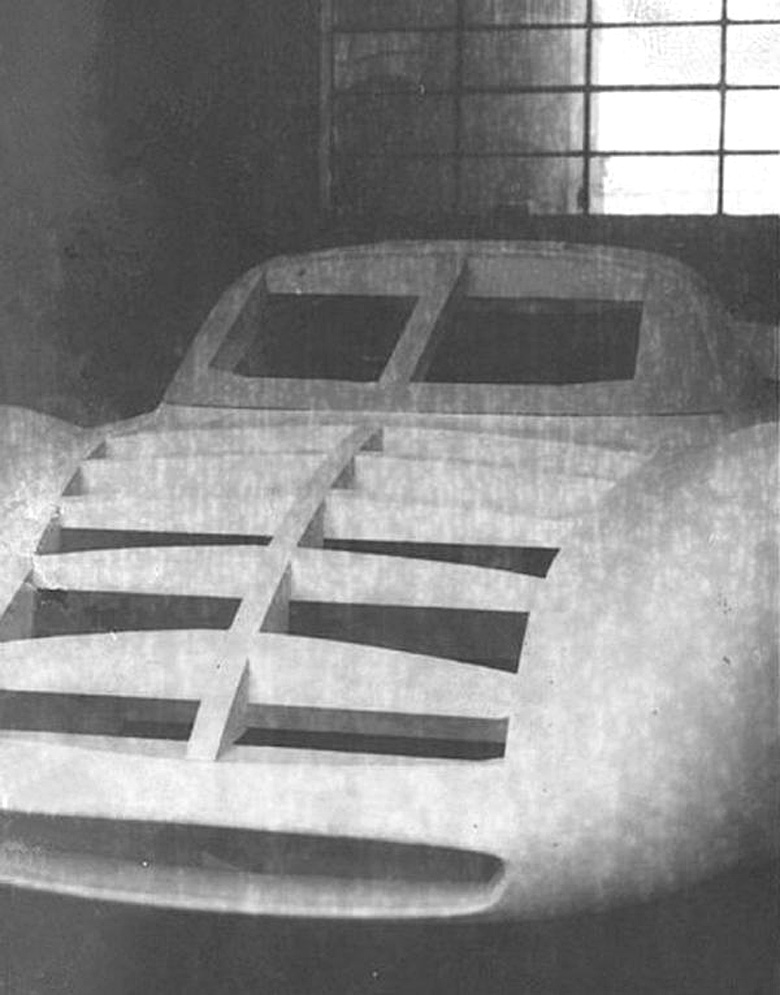

In February, 1967 Scaglione ordered the necessary wooden form for shaping the body from the Giovanni Raniero workshop in Orbassano. The form arrived in Settimo Milanese in April; a photo of one essentially like the one Scaglione used is shown below.

Wooden body shaping model from Giovanni Raniero workshop in Orbassano. Courtesy Vladimir Pajevic archives.

Scaglione continued to complain as he knew that he had only one worker available and after more than a month came a second worker from the main Alfa Romeo factory downtown at Portello. These alarming manpower shortages were not known to Scaglione when he signed that binding contract back in December of 1966.

Giovanna continues, growing visibly upset as she recalls what her father told her. “I did take as much as I could, even in the workshop, reducing me to workmanship team-leader, both for contacts with suppliers…I had to take every possible step, both in the workshop, reducing myself to working as a boss-team worker and to contacts with suppliers,” a completely frustrated Scaglione was quoted as telling his daughter.

In the meantime, Scaglione ordered two “lastrature” (full shapes) in aluminum (already cut pieces to be modelled on the wooden form) from his regular suppliers, Saracino e Lingua from Druento near Torino. The very first difficulty for Scaglione was being forced to abandon the vital assistance of his two finest Torinese shape masters, Messrs. Giannini and Pareschi, who found working conditions at Autodelta well below their own acceptable standards.

Scaglione continued his work alone lamenting the lack of almost elementary tools and (the letter still exists) asking for more help from Alfa Romeo President Giuseppe Luraghi, who ordered the detachment of two workers from Arese as permanent helpers for Scaglione, and thus he started working on the lightened version of Stradale, known as the ‘second’ prototype car with four headlights

The vehicle was conceived and ultimately completed using existing aluminum “lastratura” – lightweight construction practices – on internal components and was created over a standard steel chassis, in spite of ‘fake news’ urban legends to the contrary.

He returned to work on prototype No. 01; the lightened version No. 02 would only receive his personal attention and be completed in May 1968 after vehicle No. 3 was produced under Scaglione’s direct supervision at the Marazzi workshop.

Chronologically, Scaglione personally completed his cars in this order: first vehicle 105.33.01 ‘four headlight version’ at Autodelta; his second vehicle was 750.33.101 at Marazzi; the third vehicle was started at Autodelta in Settimo Milanese and completed as 105.33.12 in May 1968 at Marazzi…almost two months after Scaglione had been ‘fired’ by Autodelta in March of 1968!

Franco Scaglione was an extremely responsible person. When he accepted a duty to create a vehicle he believed it was his moral and ethical duty to bring the agreement to its complete and satisfactory conclusion.

That second car Scaglione completed was originally conceived as a ‘four light version’ adopted for series production. Because of changing Italian certification issues, the lower two headlights lights were no longer permitted for the street cars. Thus, the original four-light design was changed to two headlights without Scaglione finding it necessary to modify the original exterior shape. Mr. Scaglione was desperate because of bad working conditions at Autodelta and he started complaining to all the pertinent people involved; Ing. Satta Puglia, President Luraghi and director Generale Chiti for example. Chiti was irritated with Scaglione’s behavior, and explosive as he was Chiti started to act impertinent to Scaglione on more than one occasion.

The first prototype was well along in production while the second somewhat lightened car was parked next to it under a covering, having been delayed by Alfa Romeo management.

The Stradale at Goodwood’s 2011 Festival of Speed, again showing the dramatic lines. Photo by Jonathan Sharp.

There exists an internal Autodelta note dated in August 1967 listing several small changes to execute before presenting the first prototype to Luraghi, and in September the body was completed and presented at the Monza Special Cars show. Its shape was nothing short of sensational. The vehicle was internally referred to by Mr. Scaglione as the “marketing car.” However, there was not an available engine to put into the car as all were being used for racing cars. In October regular series production at Marazzi began. (Marazzi was based near Varese and involved with the production of several models of Lamborghinis.) Scaglione, although contrary in disposition and as upset as he was, moved the wooden form for body shaping from Autodelta to Marazzi near Saronno and began his work.

Scaglione had already accepted the task of having to instruct Marazzi workers how to manage Peraluman H33 used for the body of the Stradale and to supervise production of the second car not specifically covered by his contract. At the specific request of Carlo Marazzi, the assembly of the 33 Stradale would only happen under the direct control and supervision of Scaglione personally as Marazzi knew that his workers were not capable of elaborating the Peraluman metal chassis skin. Scaglione readily agreed with Mr. Marazzi of this fact although his opinion of the workmanship abilities of Marazzi factory employees was not as high as that held by Mr. Marazzi.

Under those conditions Scaglione proceeded to complete the first ‘two headlight’ version designed for production/road use. Also in October was Scaglione’s report about his progress on the second lightweight car, serial 105.13.12 .Once again this work on the racing, lightened version was not covered by his contract but he considered it his ethical responsibility. In November the first Stradale was presented at the Torino Car Show and was a positive shock. Its success was enormous despite its announced price which was among the highest on the market.

By the end of 1967 Scaglione’s report contained a description of the progress being made with car N°2 (racing, lightened version) and car N°3. The progress had been slow; the workers unskilled and Scaglione was very disappointed with his position; no longer a designer but more of a shop foreman. He was certainly an extraordinary person with nice manners but extremely inflexible in his manner. In a word, he was an artist and not technician.

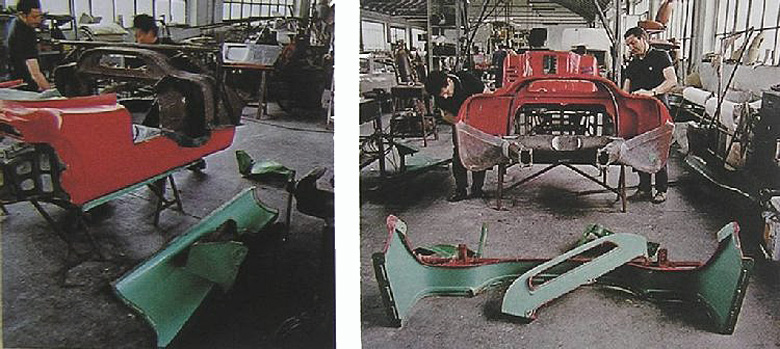

Production area showing the process of “fibra di verto” (fiberglass mounting) for the Alfa Romeo T-33/2 Daytona coupé vehicles – the same assembly area as used for the 33 Stradale – shown here at the Autodelta factory in Setttimo Milanese.

In the beginning of March 1968 Chiti informed Scaglione that his mission at Autodelta was over. Mr. Scaglione was unceremoniously fired. Though deeply embittered, Scaglione finished N°2 at the Marazzi workshop (on his own personal time and at his own emotional expense) as he had promised President Luraghi he would during the previous year. And as a parting farewell note in May of 1968 he summarized all his complaints in a three page letter to Luraghi and Ing. Satta Puliga, and two weeks later to Chiti personally. This was his very last official appeal to Autodelta, Chiti and Alfa Romeo S.p.A.

While his relationships with Autodelta were quite often very rocky for a number of different reasons, Scaglione’s most offensive confrontation came upon him when he was totally ignored in the preparation of the T-33/2 Daytona racing car, being designed and constructed in the same Autodelta building.

Giovanna painfully adds: “Although my Babbo was present daily in Autodelta, the most offensive scandal occurred to him when he was beautifully ignored during the preparation of the T-33 Daytona racing car. He was not consulted to assist in the aerodynamic preparation for the team of cars despite his reputation and history as an aerodynamicist.”

Observations from a private source

At this point in the narrative more observations are shared by our private source (only wanting to be known by his initials, R.R.P) describing some of the more detailed interactions between Ing. Carlo Chiti and designer Franco Scaglione.

“I had exchanged a letter with the late Maurizio Tabucchi about the birth of the 33 Stradale and of the spoiled relationship between Chiti and Scaglione. (There was already a river of ink about that, and the fact is, regardless to their previous excellent collaboration, the Stradale put the full stop to any of possibility of a further relationship.) It is sure that Chiti had preferences for “his” Tuscan people, and their work together on the ATS 2500 berlinetta was successful. Chiti knew that Scaglione was N°1 and easily convinced Alfa Romeo President Luraghi in favor of his selection.

“However, something turned out to be wrong later. Tabucchi (only in his private opinion) made this assumption about the relationship: Chiti was a known phenomenon with all his attributes of being a ‘spotlight chaser’. To share the public stage with Scaglione as a ‘co-star’ was not simply his game. Scaglione equally pretended his importance, or better yet, asked for that level of respect that he requested as a starting point in any enterprise where he was considered.

“To spoil the circumstances even more, there was almighty IRI government oversight agency to put the brakes on any unusual Chiti decision that he might have proposed and the existence of the IRI absolutely drove Carlo crazy in most cases. Having to listen to Scaglione and his requests (usually reasonable) probably lead to the rude reactions of which Chiti was proverbially capable.

“Tabucchi wrote something like this in his letter…my interpretation.”

Having had a deep personal and professional relationship with Ing. Chiti, R.R.P. continues:

“Chiti was substantially a roughneck with a tender soul. After his frequent explosions, he always reverted to a ‘no hard feelings old chum’ position with true sincerity. Scaglione was different. Born and educated as a noble descendant, he was spiritual with sophisticated manners but in no way less intransigent than Big Carlo. The crash was inevitable and in those difficult circumstances, it was only the question of time.

“Tabucchi, who was close friend of Chiti (imagine two Pistoia people almost the same age!) confessed that on the occasion of a 33 Stradale dispute, Chiti was unrighteous and Scaglione deeply affronted.The truth is that Scaglione never forgave all those hard words.

“Chiti later regained all his benevolence towards Scaglione and praised his work with truly convincing heartfelt words. Years later, Chiti, in speaking about the 33 Stradale experience, he described Scaglione as a “real nice person” (gran brava persona) and I think that this is the correct interpretation of those facts.”

Scaglione too, with the passage of years had softened up his judgment about Chiti and his months commuting to and working in Settimo Milanese. Chatting with the late Maurizio Tabucchi and Luca Delle Carri in the occasion of an interview for Auto Capital magazine – an article that was published, as a sheer coincidence, in the exact same month that Scaglione passed away – Scaglione declared in the interview: “With Chiti, you had to satisfy his whims, and then you could work with him easily (Il buon Chiti bisognava farlo scapricciare e poi ci si lavorare assieme…)”

Our source added more details about Mr. Scaglione:

“Then, there was a kind of legend that was born with Nuccio Bertone’s statement that Scaglione was not technically prepared for designing ‘usable’ parts for production. Nothing can be said more wrong than this, but no wonder coming from Nuccio Bertone. With all his importance acknowledged, Bertone was and remained ‘The Coachbuilder.’ Scaglione was certainly capable of any project solution but he was also ‘The True Artist’ and in continuous search for beauty in any form. He was also extremely well-informed in new technologies and true expert in aerodynamics. That is why he was so insulted when Chiti brought French expert Michel Tetu to improve the Daytona’s aerodynamics.

“Scaglione’s sentiment about Chiti’s affront to him was clear proof of the dilapidation of Autodelta secrets, and he was certainly right. Tetu never improved anything but acquired all Autodelta knowledge and used it in his later projects. However, this is another story.

“This is my reflection about Franco Scaglione and his relationship with Carlo Chiti.“

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

Read Part 5

Read Part 6

Read Part 7

Read Part 8