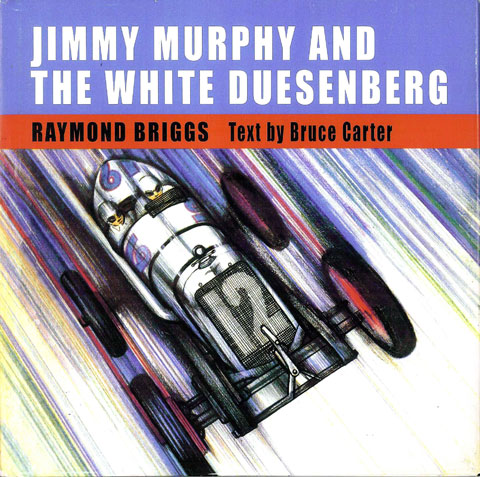

Text by Bruce Carter, Illustrations by Raymond Briggs (copyright 1968, 2006)

New Edition by Racemaker Press, LCC (2006)

ISBN 0-9766683-1-9

For ages 8 and up

37 pp (no pagination)

$20 + S/H

$40 + S/H for boxed set of Nuvolari and the Alfa Romeo and Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg

www.racemaker.com

Review: Bruce Carter and Raymond Briggs, Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg (1968, 2006)

By Patricia Lee Yongue

Appropriately, the number 12 used on the Nuvolari P3 at the Nurburgring, also identifies the car and driver celebrated in the second Carter and Briggs book reissued by Racemaker Press: Jimmy Murphy and the “beautiful white Duesenberg racing car.” In 1921, at Le Mans, this doughty pair achieved an American first by winning the prestigious Grand Prix de l’Automobile Club de France–the French Grand Prix.

It was likely not happenstance that Carter and Briggs published their Murphy and Nuvolari books for children in 1968. To traditionalists, too influential a sector of the Western world’s young people had shamefully demonstrated against the patriotism and work ethic of their parents. Fueled by media coverage, they deified raucous rock groups and peaceful folk singers alike, dressed as tramps or San Francisco Flower Children, discovered LSD, practiced vandalism while they preached against violence, and dismissed their elders, school, workplace, and country as irrelevant. The public’s general impression was that they were vagabonds traveling in psychedelically painted VWs and vans, pursuing no goals save a check from home and avoidance of responsibility.

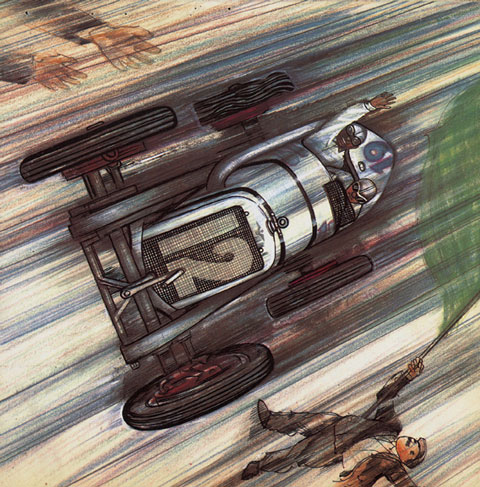

Illustrations from “Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg”.

Carter and Briggs may have thought this time opportune to re-introduce a younger generation of English speakers not only to history and the high adventure of man and race car, but also to a masculine heroic paradigm of guts, skill, determination, and patriotism. Logically, Jimmy Murphy’s story precedes Nuvolari’s because it covers an earlier era. Perhaps the story also spoke directly to those Carter and Briggs thought most vulnerable to hippie influence. Particularly in its omissions, the narrative reveals a stronger subtext of patriotism than the Nuvolari story.

On July 25, 1921, after a lengthy World War I hiatus, the French Grand Prix resumed. War weary and eager for uplift, the French counted on a Ballot victory, especially by native sons Jean Chassagne, Jules Goux, and Louis Wagner. These men set out to reclaim the championship France had lost to the German Mercedes team on the last lap of the 1914 race. Carter identifies the French Ballot drivers but he does not include the historical background; nor does he include the fact that veteran Italian-American Ralph de Palma was driving a fourth Ballot and led the Ballot team. Some of the exclusion has to do with cognitive focus and attention span and some with theme. If Carter wanted to emphasize American patriotism, he had to minimize sympathy for the French and to undercut de Palma’s presence. (De Palma would later be accused of throwing the race because of a dispute with Ballot, an issue Carter surely did not want to broach, even though the accusation was frivolous.)

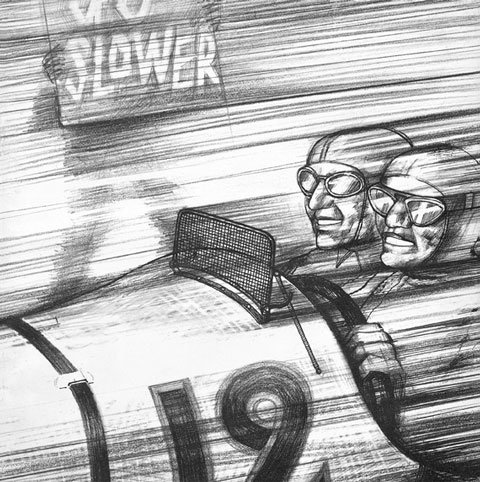

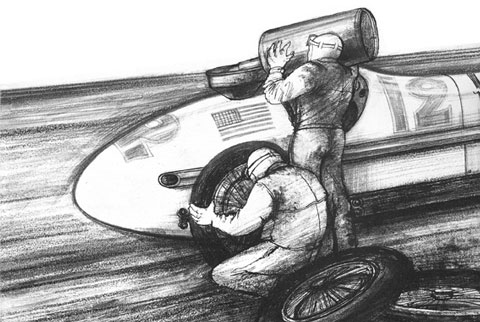

Illustrations from “Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg”.

Twenty-seven year old Jimmy Murphy (1894-1924) had his own plans for the famously fast blue Ballots and the other eight cars entered in the race, including the Duesenbergs of his teammates, fellow American Joe Boyer and the Frenchmen Albert Guyot and Louis Inghibert. Unlike the younger Americans of the 1920s who expatriated to France to party or to bemoan their country, or unlike the irresponsible 1960s San Francisco-styled hippies, Carter and Briggs might have been thinking, Irish-American Murphy, a native San Franciscan, no less, “had come to France to win the great race for America.”

Although the Duesenbergs were stout competition, with their low, streamlined bodies and “wonderful new” hydraulic brakes—“the best in the world”– Murphy’s victory wasn’t a snap . . . starting with practice, which is where Carter and Briggs start their tale.

Murphy and Inghibert were injured, Inghibert seriously enough to be replaced in the race by Frenchman Andre Dubonnet, when the Duesenberg in which they were practicing flipped over as Murphy braked hard then skidded to avoid a farmer driving his horse and cart straight into Murphy’s path. Gary Doyle, author of the excellent “King of the Boards, The Life and Times of Jimmy Murphy.” amends the story slightly. A loose horse on the track had incited the accident, and, though Murphy was driving at the time, the car was actually Inghibert’s (Inghibert along with Guyot and General Motors funded team Duesenberg’s GP entry). Having a “cut and bruised” Jimmy “looking gloomily at his smashed car” would nicely set the stage for car and driver’s mutual recovery and triumph.

Ribs bandaged and released from the hospital only hours before the race, Murphy started on the fourth row, behind a Mathis, de Palma’s Ballot, and a Talbot. Still ignoring de Palma, Carter says Murphy started behind a Talbot and a Mathis. Sore as he was, he might not win, the thought barely crossed his mind, but he would “drive flat out all the way.” Like NASCAR’s Kyle Busch today (but more sportsmanlike on and off the track), “Murphy always drove flat out. That was how you won races, he said.” Carter credits Ernest Olson, Murphy’s riding mechanic, with being “a brave fellow. You had to be brave to drive in a four-hour Grand Prix with one of America’s fastest drivers.”

Not surprisingly, then, it took Murphy only a lap and a half to snatch the lead. The illustrations as well as the text emphasize Murphy’s law of flat out driving. Because the road course was short, the pace was particularly exciting for the drivers and, as Doyle points out, also for the fans assembled around the rock glutted circuit, who got to see the cars roar by them frequently. Sometimes it was dangerous. At the treacherous “hairpin corner of Pontlieue,” as Murphy pulled his Duesenberg to “the left side of the road to take the corner,” the “crowds jumped back, fearful that the American car would charge them.”

Carter and Briggs maintain a fast pace, following even Murphy’s necessary slowdowns and trading off of first place with rapidity. The corners of the circuit, as well as the long straight—where Murphy reached “almost 100 miles an hour” before he “first touched the break pedal”—are sites of daring. Carter and Briggs typically bypass representing the famous photo of Murphy getting ready to pass de Palma on lap ten just after Pontlieue. But it is of course the final challenge that creates the drama of competition, speed, and luck.

With Murphy chasing then passing Chassagne, and Chassagne suddenly stopped dead by a shorn fuel tank, Murphy could taste victory, a mere two laps away. But he was not complacent. The car was losing water, its radiator punctured by a stone. He settled into “nursing the Duesenberg along carefully” and “praying the engine would last out.” It was red hot. He eyed the tachometer. Nonetheless, “he was ready to risk a final burst of speed if their car was challenged.”

Illustrations from “Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg”.

Then they suffered a flat tire and “lurched.” Skilled as well as fast, Murphy maintained control of his car and “skidded” to the finish line. “The flag was out.” The Stars and Stripes had won.

Carter makes sure that Murphy’s bout with Chassagne at the end does not leave his young readers disappointed. Despite no emphasis on the French spirit for most of the book, Carter finally acquiesces to acknowledging Chassagne as “the French champion.” Hemingway style, Carter creates equality between hero and rival. Indeed, Carter, using fancy irony, parallels Murphy “looking gloomily at his smashed car” in practice with Chassagne and his mechanic “standing and gazing ruefully at their gallant car” two laps from the end of the race.

As he does at the conclusion of the Nuvolari story, Carter provides an appendix to Murphy’s story. He gives a brief biography of the driver and a technical description of the car.

My eleven-year-old reader, Ty Gadberry, I am pleased report, read the entire text from cover to cover. He expressed sadness at learning that Jimmy Murphy died in a racing accident so soon after winning the great race, but he loved the excitement of the race and the crowd and Murphy’s ambition to win. Ty said that the detail is so wonderful“I felt like a passenger in Jimmy’s Duesenberg,” a feeling the drawings greatly assisted. The only detail Ty did not understand was the practice of starting at intervals and hence missed out on Murphy’s impatience to get going. Other than that small item, Jimmy Murphy and the White Duesenberg gets “a full five stars” from Ty.

(Gary Doyle is also the author of Ralph De Palma, Gentleman Driver. For information about Doyle’s motorsports writing, visit his website, www.king-of-the-boards.com)

Wow! This book is worthwhile if for nothing but the cover illustration. Lunch money is being saved…

Jean Chassagne was married to my Tante Amy

and i stayed in his house at Maison LaFitte in 1952 when we took my french great grandmother to see her family as she had not seen anyone since the war. We stayed a month visiting different family members every day and eating wonderful food. Tante Amy was a very elegant lady.