By Burt Levy

The huge annual “International Challenge” vintage race at Road America is one of the must-do events on the vintage calendar—and I was privileged to be there, sometimes on the sidelines, sometimes covering it for magazines and judging in the concours and sometimes right in the thick of the on-track action as the event became what it is today. It all started for me back in the early 1980s, when my longed-for “racing career” was going exactly nowhere. I’d begun racing in 1971 in a series—maybe more like a plague?—of self-wrenched, under-funded, nickel-rocket and borderline lethal Triumph TR3s that rarely finished a race. Then I met Joe Marchetti.

I’d made some interesting friends in and around the local racing scene, and among them were some genuine, professional-mechanic types—late friend Ed Tillotson among them—who raced a long-in-the-tooth/short-on-money Lotus Cortina sedan and worked at an incredibly nondescript garage building on Halsted Street, literally walking distance from our apartment. Ah, but what magic was hidden inside those windowless concrete walls! The business was officially called TOTOH (for “The Old Town Oil House”) because it used to be located many blocks and several tax brackets south on Wells Street. Only then Wells Street—in fact, all of Old Town—became the hot, trendy and happening “place to be” neighborhood in Chicago. Bistros, bars, boutiques and head shops (remember those?) cropped up like colorful weeds, and The Second City’s theater blossomed with laughter and satire at the end of Pipers’ Alley, which was lined with narrow storefronts where you could buy everything from beaded or fringed clothing to incense and Patchouli Oil to fancy roach clips. But the neighborhood’s ascension as “the hip place to be” drove all the regular, pay-your-rent-and-lock-up-at-the-end-of-the-workday businesses elsewhere.

Which is how TOTOH wound up in that dark, anonymous building on Halsted Street, not far south of Belmont. And I’d wander over there while walking the dog, head around to the overhead door on the alley with the big “NO PARKING” sign on it and peek in. Or knock if the door was down, and eventually Ed or Cliff or whomever would let me in so I could marvel at whatever might be inside. And there was always stuff worth looking at. Ferraris. Maseratis. An occasional old Bentley, even a speedboat or a racecar or two. TOTOH had some very interesting and unusual customers, many of whom wanted to remain anonymous as far as the general public and the I.R.S. were concerned. I eventually discovered that a lot of the work—particularly on the Ferraris—was for a highly successful local restaurateur named Joe Marchetti, who bought, sold and traded in used Ferraris and other, mostly Italian exotica as a passion-fueled sideline to running, along with his brothers, arguably the most famous and successful Italian restaurant in Chicago, The Como Inn.

Joe traded up, down and sideways in used Ferraris and such, and TOTOH came into the mix when one of the cars he’d bought (or one he was trying to sell) needed a little mechanical attention. Eventually Joe had a showroom and his own mechanical shop around the corner from the restaurant at 825 W. Erie, but when I first became aware of him, TOTOH was doing a lot of Marchetti’s work.

Early summer of 1985: The just-finished AUSCA Duetto Joe sponsored and Burt built and campaigned parked in front of Joe’s Ferrari/exoticar shop and showroom at 825 W. Erie St., just around the corner from The Como Inn.

Joe occasionally ran afoul of the “legitimate” (read: “franchised”) Ferrari dealers in the Chicagoland area thanks to his own connections in Italy that may have extended all the way up to the administrative offices at the factory in Maranello. He seemed to be able to come up with low-mileage, “used” examples of desirable Ferrari models when the “real” dealers in and around Chicagoland had trouble getting inventory. It was a sore point with them, and I remember, years later, their lawyers made him paint over the huge, 2-story high Ferrari prancing-horse logo on the side of his showroom-and-shop building on Erie Street.

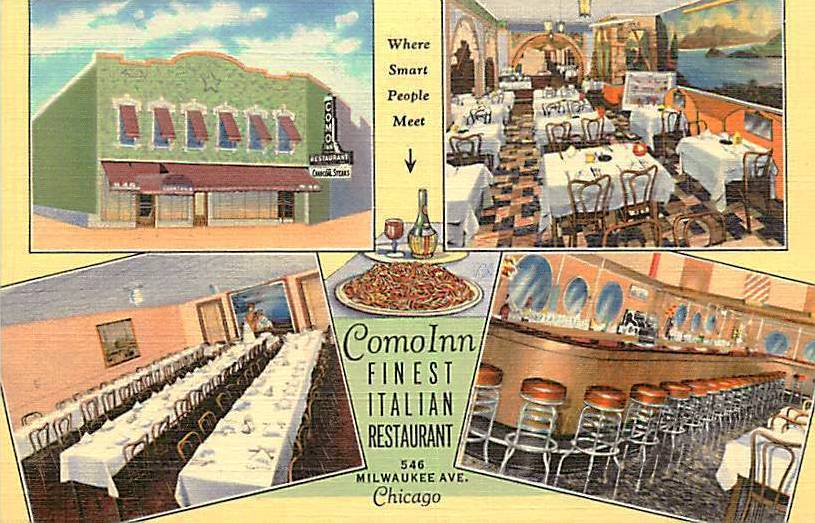

Joe’s father Giuseppe emigrated from Tuscany in the 1920s and, along with his wife, opened up a simple, neighborhood-style Italian restaurant on the triangular northwest corner of Milwaukee Avenue and Ohio Street, not far at all from Chicago’s downtown “loop” in 1924. It grew and prospered over the years, adding one additional dining room or upstairs meeting room at a time until it became a maze of fairly intimate smaller rooms—each with its own style, ambience and décor. Joe, the eldest son, possessed a promoter’s hustle and an impresario’s spirit and drive and took control of the operation after his father’s death.

It was not always smooth sailing between Joe and his brothers—I’ll leave it at that—but one was a brilliant interior designer who put a very special and individual look, feel and ambience to the dining rooms. Another brother was a gifted landscape architect, who turned the family’s estate in the southwestern suburb of Lamont (on the same plot of land, I believe, where his parents first camped in the early days before they could afford a house) into something out of The Great Gatsby or Citizen Kane. It was the perfect setting for the “Ferrari Parties” Joe put on every summer for his car friends and customers. The estate was called “Montefiori”—flower mountain—and the landscaping was incredible. Bright, flowered gardens swept this way and that, peppered here and there with tall, airy cages featuring color-matched pairs of parrots, macaws and cockatiels—there was even a little petting zoo for the kiddies—plus reflecting ponds where black swans glided gracefully across the water. What a place! And Joe would bring his catering cooks and wait staff to prepare and serve the lunches—Italian-style buffet, of course—plus wandering musicians for appropriate accompaniment.

And the cars! In the early days, it was mostly front-engined, V12 Ferraris—always my favorites—with lots of Daytonas and GTBs and Short-Wheelbase Berlinettas, plus a few scattered eye-poppers and jaw-droppers like the ex-King Leopold of Belgium 375MM with gleaming black paintwork and parrot-green leather interior. Or the time Joe had somehow gotten his hands on the first 288 GTO anyone had ever seen—the franchised dealers couldn’t get them yet—which was the first-ever turbocharged Ferrari GT and, based on the lightweight 308, possessed of absolutely scalding performance. Ever the showman, Joe had it hidden, of all things, inside a small, odd-looking mound of hay, right in the middle of the show field. He scowled darkly when he told people the landscapers had left it behind and that heads would surely roll because of it. At exactly the right dramatic moment, the 288 fired up and came exploding out of that haystack like it’d been shot from a cannon. Well, that was Joe.

I vividly remember the day I dropped by his Ohio Street showroom-and-shop and he handed me the keys to the 288 and told me to take it for a spin. By then we knew each other pretty well and I’d done some race-driving for him, but we’ll get to that in a moment. I went outside and fired up the 288—the engine note was nothing special compared to the classic V12s I loved, and muffled on top of that by the turbos—but I drove it gently west to Milwaukee Avenue, which was a patched, pock-marked and typically uneven city street that never had much traffic except at rush hour or when cabs swarmed around The Como Inn like bees around a hive during lunchtime or after 5pm. The rest of the day it was generally empty, and truckers and delivery men regularly used it as a quick way into or out of the Loop from the northwest side. I looked both ways and the coast was clear, so I turned right and floored it. Hey, he wanted me to see what it could do, didn’t he? And—at first—I was underwhelmed. Disappointed, even. The car didn’t exactly stagger, but it didn’t exactly leap forward, either. And just when I was about to mutter “WTF?” the boost kicked in and I almost spun around just trying to go straight! The power on boost—especially on this patched-and-uneven city street, was utterly explosive. I grabbed second and, a heartbeat of lag later, more of the same… WOW!

I had no idea why anyone would want that kind of nuclear-option performance in an everyday road car. It seemed crazy. But then, you can buy hotted-up econoboxes that can offer you nearly that kind of burst today. Only without the style. The passion. The panache…

Joe understood all of that. And it was his pleasure to not only share in that special Ferrari experience, but to host it. At any Joe Marchetti event, he was always there, often whipping around on a bright red Vespa and sporting a big straw hat, a smile like a Klieg light and eyes darting around like a cornered ferret, making sure everything was being done properly and that everyone was happy. “How was the pasta?” he’d ask anyone and everyone he ran into. “How are the cars?” “Did you like the desserts?”

That was Joe. The important thing was that each car, each party, each event had to be better and more memorable than the last one. He couldn’t help himself.

The Como Inn evolved over its decades and became the place to get Italian food in and around downtown Chicago. The meals were consistently good—all the usual staples like spaghetti Bolognaise and linguini with clam sauce (red or white) and, oh, have you tried the gnocchi?—and the collection of smaller, more intimate rooms and private, upstairs meeting rooms brought in everything and everyone from family celebration dinners to visiting conventioneers eager to devour the delights of Chicago to salesmen trying to impress or loosen up prospective clients at three-martini lunches to city hall movers and shakers quietly trying to set up deals or arrange kickbacks to union-board or board-of-directors meetings to clandestine, upstairs parties for sad-eyed men with odd, ominous nicknames whose photos you might find tucked away in FBI files. They all came to The Como Inn, and Joe knew and dealt discretely with all of them. My favorite memory of The Como Inn, besides the many fine and filling meals I had there, was of the gently lit, arched entrance hallway that led to a fork—one set of rooms off to one side, another set of rooms off to the other—and Joe’s desk right there at the intersection. It wasn’t huge—understated, in fact—and there was never a clutter of unresolved papers on it. He was rarely at that desk unless he had some specific person to meet, task to complete or deal to close. Joe had a multitude of balls in the air and plates spinning on sticks—always!—but he seemed to glide right through it all without obvious effort. That was part of his genius.

Another thing: just past Joe’s desk, lining the dimly lit stucco wall, were a series of very small, hidden-away dining booths with gauzy but opaque-enough curtains on each one. They were the perfect setting for an intimate meeting or rendezvous with someone you wanted to see but didn’t want to be seen with. I leave it to your imagination what sort of deals or shenanigans took place in those booths during lunch and dinner time…

Part 2 coming soon…

I loved the Como Inn as a boy and was always impressed when Joe would welcome my Dad by name. We were there every year for Thanksgiving dinner, amongst other special occasions. What a gem that place was and couldn’t agree more with your assessment of Joe. Nicely done Burt, looking forward to the next installment.

Joe Marchetti and the Como Inn were headquarters for Ferrari lovers in Chicago. The restaurant was the best in town, Joe’s nearby International Motors was always filled with Ferrari exotica, and Joe was always around and he knew everyone of his customers by name. His Ferrari events at Mirafiori in Lamont were not to be missed. And then he developed his historic races at Road America. Joe was one-of-a-kind and will never be replaced. He left us all too soon. But Burt Levy tells the tale as only BS can — splended stuff.

Alan Boe