Earlier this year VeloceToday presented four articles on the pioneering Tatra, with insights from two owners and Karl Ludvigsen, who also owned a T87 in the 1960s. The articles prompted a lot of responses, including learned help from Tatra expert Ian Tisdale. At the same time, Cindy Meitle sent us a copy of a new book about Josef Ganz, another pioneer who advanced the concept of an aerodynamic rear-engined people’s car with his “Maybug”, a lightweight car much like the prototype Tatra V570, which in turn was much like the Porsche-designed Volkswagen. Typically, Ludvigsen was on this story long before the book was published, noting in detail Ganz’s role in an article, “Origins of the People’s Car” in Automobile Quarterly, V45 No, 2, in 2005.

Earlier this year VeloceToday presented four articles on the pioneering Tatra, with insights from two owners and Karl Ludvigsen, who also owned a T87 in the 1960s. The articles prompted a lot of responses, including learned help from Tatra expert Ian Tisdale. At the same time, Cindy Meitle sent us a copy of a new book about Josef Ganz, another pioneer who advanced the concept of an aerodynamic rear-engined people’s car with his “Maybug”, a lightweight car much like the prototype Tatra V570, which in turn was much like the Porsche-designed Volkswagen. Typically, Ludvigsen was on this story long before the book was published, noting in detail Ganz’s role in an article, “Origins of the People’s Car” in Automobile Quarterly, V45 No, 2, in 2005.

Ganz was involved with Tatra for years, so we asked Tisdale to write a review on this new, well documented book about Ganz, who claimed to have ‘invented’ the Volkwagen. Tisdale is well qualified to sort this all out, as he does superbly in the review below. [Ed.]

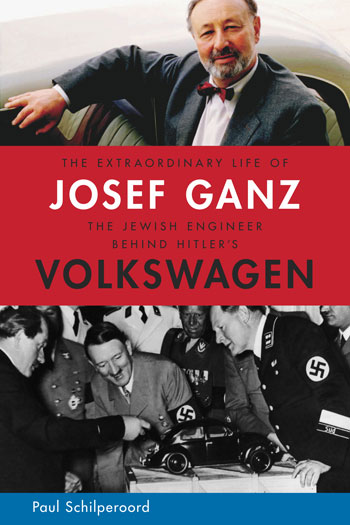

Josef Ganz, The Jewish Engineer Behind Hitler’s Volkswagen, Paul Schilperoord, RVP Publishers, 2011 ISBN 978-1-61412-201-2 (hardback). Available from Amazon.com. About $18 for softback edition.

By Ian Tisdale

So, what’s behind this cover, with its portentous title separating an image of Josef Ganz, unfamiliar, but appealing and dapper, and the well-known shot of Ferdinand Porsche demonstrating a model of the KdF-Wagen to Hitler and his swastika’d cronies? First and foremost, a very well-paced and well-written story that quickly becomes hard to put down; the general reader will find this as entertaining as a good novel, and car enthusiasts of a variety of persuasions will want to find out what new insights are being revealed. Some Volkswagen and Porsche followers will approach this new book keen to review fresh information on their area of interest, while others, possibly the majority, will be primed to defend the established narrative. Meanwhile, the stature of the Beetle is such that other factions already attempt to lay claim to at least some of the VW provenance, and they will want to see to what extent the Ganz exposure supports or erodes their case.

1928, Ganz is working on a Dixi for a test drive. In the foreground is his Tatra T11, which utilized a backbone chassis, swing axles and an aircooled engine. Ganz was impressed and influenced, but already had plans to design a similar car with the engine in the rear, allowing for a more aerodynamic body.

It was while starting to research for a planned Volkswagen book that writer and journalist Paul Schilperoord came upon references to the largely forgotten Jewish automotive engineer, designer and commentator, Josef Ganz of Austria. Having identified an intriguing avenue, as obscure as the VW is famous, Schilperoord changed course and committed himself to what turned into a five year mission. The resulting book was first published in his native Dutch, seriously limiting its audience, but subsequently appeared during 2011 in German and at the end of the year in English.

1929. Ganz backs the Tatra up the stairs in a demonstration of the advantages of independent rear suspension. At the time, swing axles were the only design option for rear independent suspension.

Based in the Netherlands and working in Italy, the author is now caught up in an ongoing round of international presentations, and radio and TV and appearances, because his book’s rather cumbersome title has proved to be an attention grabber. The combination of Hitler, the promise of a sensational reappraisal of the familiar Beetle story and the delightful irony of the National Socialists’ people’s car being the brainchild of a Jewish engineer has had the desired effect – strong sales and plenty of promotional opportunities.

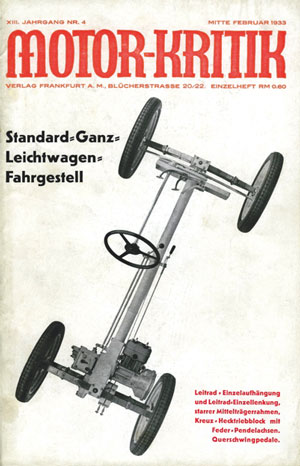

1930. Ganz was the controversial but highly respected editor of the German ‘Motor-Kritik’ magazine which touted the advantages of IRS, rear engines and streamlined designs. But what Ganz wanted to achieve was to incorporate all those elements into a very inexpensive light car suitable for the German workers.

The definitive Porsche-Volkswagen, fully worked out by 1938, was not a plagiarized Josef Ganz formula that would be forever credited to unworthy heirs. Schilperoord, having cleverly maxed his audience with his provocatively assertive title, weaves the results of his scholarly research into a calmly written biography. We are led through the public and private life of a man on a mission to encourage and persuade a conservative and unimaginative domestic motor industry into producing good cheap vehicles for everyman, an objective that in due course was, indeed, embraced by the Nazis. And we follow his logic in proposing that cars for the mass market must be designed from the ground up with that objective, rather than being scaled down versions of existing large cars. A Ganz formula develops, and to promote his ideas he uses as his platform his editorship of Motor-Kritik magazine, that he raises from insignificance into an increasingly challenging thorn in the industry’s side.

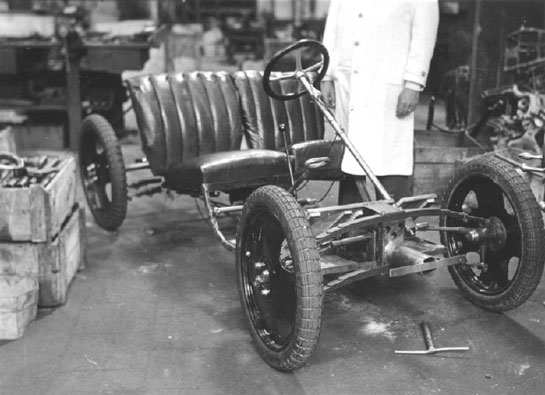

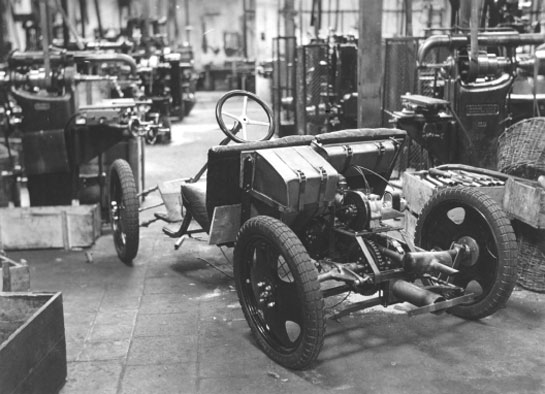

1930. In 1923, Ganz made drawings of a very small car with rear mounted engine and independent suspension and constructed working prototypes. But his first real car was built by Ganz for the motorcycle company Ardie. The prototype featured a steel tube for a backbone chassis and independent front suspension. A working chassis was completed in August of 1930.

The formula to which he devotes his life is, inevitably, an amalgam of existing inventions, as this book acknowledges. In its essentials it consists of a central spine chassis, air-cooled rear engine, independent suspension with swing-axles at the rear and a sloping ‘streamlined’ front, plainly a summary that conjures an image of the Volkswagen, the word itself having been debuted by Standard Superior for its Ganz-designed car. The Tatra T11 that Ganz owned had the independent swing axles seen on Edmund Rumpler’s 1921 ‘Drop Car’, a central tube chassis and an air-cooled flat-twin engine, albeit at the front, and he knew its designer. The Tatra, while while one of his influences, was no ‘people’s car’. Relatively compact, its engineering was a down-scaling of its manufacturer’s large cars for the bourgeoisie and, in aiming for ‘small and light’, Ganz’s direction is distinct from Porsche’s.

Like Citroën’s later 2cv people’s car, the Beetle is not small, but well able to transport four adults in comfort and at speed. Ganz’s cars were ultra-light, low, and often open to keep costs down, and he employed small single or twin-cylinder engines. Crucially, he adopted an engine position just ahead of the rear axle, as seen on Rumpler’s car, on the 1922 San Giusto and on John Tjaarda’s large Sterkenberg proposals. Although he was engaged as a consultant by, among others, Mercedes-Benz and contributed to its 120 and 130 ‘heckmotors’, he strongly disapproved of the decision to adopt what he described as an ‘outboard motor’, a view that M-B would have benefited from heeding as their chosen power plant was an iron in-line ‘four’.

1930, From the rear, the Ardi-Ganz engine drive train unit and IRS can be clearly seen. Ganz would spend years applying for patents and trying to convince both large and small firms to construct a vehicle similar to his ‘volkswagen’. Ganz referred to his design as the “Maybug”, predating the famous ‘Beetle’ nickname for the Volkswagen.

So, Schilperoord’s readers learn that Josef Ganz, a resourceful engineer and tireless campaigner, contributed very significantly to the context in which the KdF-Wagen would emerge, ultimately putting himself in harm’s way as a consequence of his strident campaigning and ethnicity. The basic layout of his designs, incorporating innovative existing ideas, would help pave the way for what would emerge from the destruction of WW2 as the world’s most popular car, carrying both the official name Volkswagen and the Beetle nickname that he had come up with. But the VW is not Ganz’s car. Rather than his lightweight fabric or aluminum, often open 2-seater designs with their little rear-mid-mounted engines, the Beetle was an advanced semi-monocoque shell with a robust compact and sophisticated, but outboard, lightweight flat-four engine and innovative torsion bar suspension. It was the ‘proper car’ that Hitler had demanded, developed by Porsche with authority to make free use of all German patents, and could provide cheap family transport having been designed specifically for Ford-inspired mass production.

This long overdue exposure of the charismatic and talented Ganz fully deserves the attention that it seems to be generating, but needs to be seen in context. Readers of all kinds, apart from the Internet’s unsavoury community of anti-semites, are bound enjoy it and it will add significantly to the big picture of automotive development between the world wars, but some will be left still uncertain or confused about the Volkswagen’s authorship. After a recent Paul Schilperoord presentation at Sandown Park, in England, an appreciative member of the audience asked “So, can you tell us what Ferdinand Porsche’s contribution to the VW was?” Make no mistake, Dr Porsche and his resourceful team remain unarguably the Beetle’s creators and the Nazi administration, however degenerate, made it possible through its ability to brush aside the agenda of the German automotive establishment and to plan for production on a grand scale.

1933. Berlin Motor Show. Ganz’s earlier prototypes had evolved and another motorcycle company, Standard, began to produce a small car called the Superior based on Ganz’s Maybug design. It appeared at the Berlin Motor Show which was attended by Adolph Hitter. The Standard Superior was a great hit of the show, not unnoticed by Hitler.

A very good book, then, as reflected by the widespread media response. Injecting fresh controversy into established perception is a familiar marketing ploy, often sensational rather than constructive, opportunist rather than serious. However, Paul Schilperoord’s initiative in shedding light on the life of a significant but abused and obliterated participant in the development of the motorcar has been carried through responsibly and professionally. Title, notwithstanding, he has not sought to deify his subject or to undermine the reputations of others, but to fill a knowledge gap that it is fortunate that he identified. Schilperoord introduces his readers to “the Jewish engineer behind Hitler’s Volkswagen”, not to the car’s creator or to its only influence. That seems fair.

____________________________________________________________

About the Author:Ian Tisdale resides near Oxford, England. In 1992, he founded Tatra Register UK, the world’s only English language single-marque Tatra club; plans are afoot to establish a North American chapter. Having trained as an architect, his career has been in logistics. He now combines work for his wife Kirsten’s supply chain consultancy with freelance car-related journalism, driving trucks and coaching. He also holds a private helicopter pilot’s license. Ian and Kirsten currently have three of the six Tatras they have owned; a 1938 T97, a 1968 T603 and a 4.3 litre 1996 T613 Mi Long M95, all of which are used year-round and routinely taken on European tours. His interests include left-field predominantly rear-engined cars, inland boating as well as industrial and engineering history.

Four Tatra articles in VeloceToday:

This is not a ‘very good book’. It is a highly biased and repetitive polemic that is seriously damaging to the reputations of many, including Ferdinand Porsche. It is handsomely produced and illustrated, which gives it a veneer of authenticity, but the author’s obvious attempts at every turn to boost the reputation of Ganz while belittling the work of others sticks in the craw. Ganz’s story is very interesting and the author has told it well. How deeply regrettable that he took such a sensationalist approach to draw attention to his book.

Thanks for this detailed and critically analyzing review on this book. However, I must add some aspects which may illustrate how much this book is highly questionable from the automotive historian’s point of view. Paul Schilperoord really is on a mission – and it seems as if he has lost the necessary distance historians (just like journalists) need, to maintain a critical point of view.

First of all, we may examine the appendix listing more than 400 references: Most of them come from “the author’s archives” – letters from or to Josef Ganz or documents from Ganz’ environment. I can’t see why a history/biography/story exclusively based on these rather tendencious sources should be acclaimed to be the result of “historic research”. More than once, Schilperoord has gone too far in taking Ganz’ notes for granted.

His statements on Hans Gustav Roehr may serve as an example, considering that this name – just like many others in the book – is barely known outside Germany. Automotive historian Werner Schollenberger has researched the Roehr history for decades, disposing of archives that he would have given access to, if Schilperoord had asked during his process of writing – but apparently, the latter doesn’t even know about their existence, although Schollenberger’s website and contact details are perfectly detectable on the net (this is also true for the Stoewer Museum and its considerable resources, that Schilperoord has never been seeking advice from as well. No, the Stoewer V5 has not a five-cylinder engine…).

Towards Josef Ganz, the Roehr family, however, never showed any sort of hostility: „It was rather a deep sadness that they expressed about the problematic situation that occurred between Roehr and Ganz at the time“, Schollenberger says in conclusion of the interviews he made and the documents that he has studied. Furthermore, there is no evidence that Hans Gustav Roehr was a „personal friend“ (as Schilperoord says) of Hermann Goering.

And Roehr’s wife Marquerite (not Margaritta; her name is wrongly spelled throughout the book) was liked by the Roehr workers, not hated – very much to the contrary of what the author says! Schilperoord has based his conclusions here on the testimony of a former employee who had been dishonorably released from the company; by sanity and reason, any historian would be very cautious with such material.

That said, I consider it as morally objectionable to finally impute an intended murder of Josef Ganz to Hans Gustav Roehr and others, considering the one-sided state of research. That said, I would suggest some sort of persecutional mania on the part of Josef Ganz anyway – admittedly, he was diagnosed (see note 437) with schizophrenia by the end of his life, and that fact alone increases the need to cross-check any Ganz-related source!

I could list a lot more examples proving that Schilperoord’s book hasn’t been written „responsibly and professionally“: from falsely underlined photos to obvious mistakes that German-speaking historians (as well as historians specializing in the german automotive history) would notice right away. Schilperoord doesn’t speak German, but he declares to be perfectly able to read and understand (!) the language – he better is, since most of his sources were written in German language. I won’t comment on that.

So, „The extraordinary life of Josef Ganz“ is not a good book. It can be a good read, though – like John Irving’s latest novel, which is – let’s name it! – pure fiction.

Having read Karl Ludvigsen’s as well as Frederic Scherer’s comment, I understand why Herr Schilperoord never responded to my suggestion of discussing his book.

Nervertheless I would like to highlight the fact that Sch.’s book reminds people of a more or less forgotten name in automotive history.

In any case Josef Ganz was one of the first, if not the first ever who called for a “Volkswagen” in his article “Wir brauchen den deutschen Volkswagen”.

Under separated mail I will send some pictures of Ganz’s restored Maikäfer, for many years conserved by Michael Wolf Graf Metternich, now owned by Dieter Dressel of Central Garage, Bad Homburg.

Martin Schroeder

I do not know Mr. Ian Tisdale’s parameters to consider a book as being a “well-written story” which I personally do not agree with – I also do not know how deep Mr Tisdale has studied the real VW Beetle story – which he may have refer to as “the established narrative”. Shilperrord’s book shows too many historical mistakes and is completely biased, but it can convince those who never had contact to the automobile history, specifically to the incredible Kdf or better said VW Beetle genesis – a saga that started in 1903 with the invention of the swing-axle patented by Edmund Rumpler (from whom Mr. Ledwinka learned a lot, by the way). This book could be a Josef Ganz’s biography, but this would not sell. The mix of poor Jewish engineer being robed by Hitler and “his boys” with the VW Beetle history… Yes! This sells for sure, but as it was presented it is not much more than a sad, cheap and worthless satire.

The VW Beetle genesis did follow the so called “Zeitgeist” from the thirstiest for a small popular automobile it means: central tube chassis, four wheels independent suspension (here enters the Rumpler’s swing-axle), aerodynamic form and rear air-cooled flat four engine. Many concepts based upon this “Zeitgeist” were developed by different engineers, Josef Ganz did copy this tendency in his designs and being an egocentric person he believed that he “invented” principles that were already known. The book itself repeatedly tells from whom Ganz did copy principles and details.

Another mistake and a silly Ganz’s statement was to say that he invented the the expression Volkswagen, as originally stated by Shilperrod in several interviews. For one who understands German it is clear that initially this word (that was often used short after the First World War) was a substantive which in German begins with capital letter, in other languages this does not happen. Volkswagen means “people’s car” and was a wish of many Germans since the First World War. Then, as the Nazi regime decided to have a car for the people, this word changed to a car’s name without any graphical change, and after some time it become the name of a company that was to manufacture the car. Shiplerrord’s book uses the word Volkswagen indistinctly, thus forcing confusion on the readers. Since he dose not speak German I do not know if he is able to understand these differences.

Since I’m recognized as a VW expert (I already wrote two books about the VW Beetle) I was invited by a Brazilian Newspaper (Estado de Minas) to state a question to Mr. Shilperrord, which I state below with the corresponding answer:

QUOTE 1

Alexander Gromow, brazilian historian and Beetle enthusiast, says that the project is part of the Zeitgeist of the period. How do you see that?

UNQUOTE 1

QUOTE 2

Shilperrord’s answer (part): … the Beetle was indeed the result of the Zeitgeist of the period, but Josef Ganz played a very important role to develop the basic concept for the Beetle and propagate this idea…

UNQUOTE 2

If Mr. Ganz had such an important role, what can we say about Rumpler, Ledwinka, Béla Baréniy, Gustav Röhr and many others that forged the “Zeitgeist” the effectively lead to the final concept developed by Ferdinand Porsche and his superb crew of engineers? A car that conquered the world!

I know about Shilperrord’s intention to write this book since November 2005 and I wrote an article in Portuguese rebating the basic arguments of this pamphlet, you may use Google Translate to read it:

http://www.maxicar.com.br/old/gromow/colunista_gromow_0809.asp

I could state a lot more, but this post is already too big. I would like to finish with the partial statement of Mr. Dieter Landenberger, Head of Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche Aktiengesellschaft Historical Archive, which I relay in German for the sake of accuracy

QUOTE 3

Schilperoords darin beschriebene These beruht darauf, dass der von Josef Ganz im Jahr 1933 vorgestellte „Standard Superior“ das Konstruktionsprinzip des Volkswagens vorwegnahm, die Nazis dann die Entwürfe stahlen und Dr. Ferdinand Porsche mit dem Bau des Volkswagens beauftragten. Diese Mutmaßung einer politisch unterdrückten Vorreiterrolle des jüdischen Automobilkonstrukteurs Josef Ganz hält einer wissenschaftlichen Analyse unseres Erachtens jedoch nicht stand und wird von unserer Seite widersprochen.

UNQUOTE 3

Free translation:

QUOTE 4

Schilperoord’s therein described thesis rests on the fact that the “Standard Superior ” presented by Josef Ganz in 1933 anticipated the principle of construction of the Volkswagen, the Nazis then stole the designs and commissioned Dr. Ferdinand Porsche with the construction of the Volkswagen. This presumption of the leadership of a politically oppressed Jewish automobile designer Josef Ganz does not withstand a scientific analysis according to our point of view and is contradicted by us.

UNQUOTE 4

I believe that this concludes this subject!

The book was published in Portuguese by Editora Alaúde.

http://www.alaude.com.br/alaude/product.asp?template_id=62&partner_id=1&nome=A+Verdadeira+Historia+do+Fusca&dept%5Fid=110&pf%5Fid=978%2D85%2D7881%2D055%2D9&dept%5Fname=Automobilismo+%2F+Mobilidade

Just one note to Frederik and Alexander: Paul Schilperoord’s mother language is Dutch but he is speaking and understanding German, too.

Having studied Ganz as far as practicable without actually buying the book i have three points.

1. The cover of Motor Kritik very often features Ganz himself and his products. He comes over as a complete narcissist.

2. The Standard Superior seems to have too much weight on the rear wheels. Volkswagen had spare wheel and fuel tank in front for better distribution. I think the Superior didn´t sell because it sucked. Just like the Heck-motor Mercedeses Ganz helped out with.

I think the idea behind this book is absurd. All engineers work off the ideas and designs of our predecessors. What Porsche did was marry alot if good technology into one package. I think if Ganz were alive and you looked him in the eye and asked the question, he would not take the creadit.