By Pete Vack

June 1956, Sport Cars Illustrated, Very Sincerely Yours

Ludvigsen gets behind the wheel of

Gus Andrey’s T61 Maserati for an SCI

track test in the April 1961 issue.

“We can say without a doubt that [Ludvigsen’s article on the Ferrari 750 Monza] is the most exhaustive piece of literature available on Enzo’s fantastic four barrel, and this includes Ferrari factory literature. We guarantee that [our new technical series] will delight even the most sharp-eyed reader.” With that short paragraph, John Christy launched the long and fascinating career of Karl Ludvigsen. Sports Cars Illustrated (later Car and Driver) itself had recently been purchased by Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, intent on capturing the hobby magazine niche with a series of magazines such as Flying, Hi-Fi and Photograph.

Ziff-Davis, savvy enough to dispense with most of the old editorial staff, brought in Ken Purdy as Editorial Chairman. Ken in turn brought in John Christy as Managing Editor, Jesse Alexander as European Editor, Griff Borgeson as West Coast Editor and carried over Karl from the old regime as Technical Editor while the entertaining Dennis May charmed in from England. If ever there was an editorial dream team, this was it.

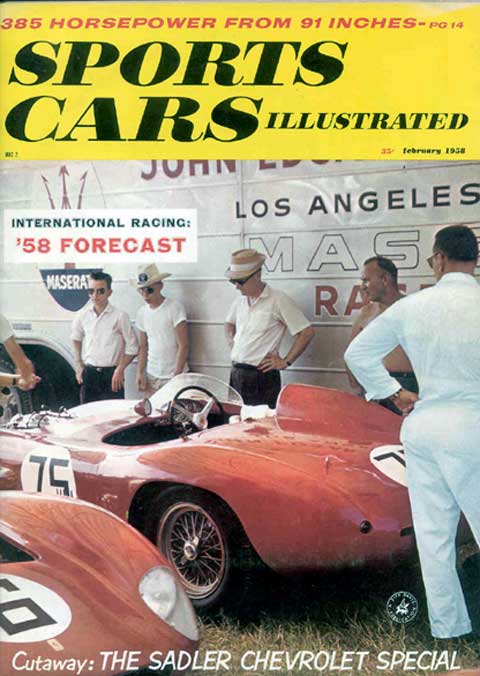

A typical issue of SCI in the late 1950s featured this Tom Burnside shot of the John Edgar racing team. Inside, Ludvigsen delved deeply into the Alfetta 158/159 GP cars.

Immediately, MIT-trained Ludvigsen — then 22 — raised the bar on automotive technical journalism. He assumed his audience was just as intelligent as he was. He wanted to learn and report the details, the measurements, the materials, the makeup of the cars he at times seemed literally to dissect. He was obsessive, accurate, compulsive, amazingly lucid and asked more questions that anyone had ever dared ask before, and demanded answers. His technical knowledge and his ability to translate obscure details into layman’s terms were unsurpassed. His articles were often filled with graphs and diagrams and always photos of brakes and chassis and suspensions. Ludvigsen took a car from the head of the engine right down the amount of toe-in of the front and rear suspension. Every mechanical aspect was described in often excruciating depth. In the July issue, he tore into Candy Poole’s PBX. The Crosley engine was notable for its overhead camshaft and, as Ludvigsen wrote, “The cams attacked the inline vertical valves through long skirted thimble tappets and adjustment shims. Standard Crosley valve timing kicks the intake valve open five degrees before top center and closes it 50 degrees after bottom center, giving a duration of 235 degrees.” This in a magazine that had, only a few months earlier, been noted for presenting the latest in women’s sports car fashions.

Unlike many others, Karl not only understood engineering but was able to weave fascinating history into the same sentence, making the reader aware of the historical background as this, from the Monza article about the front suspension demonstrates: “Experimental Monza front suspensions also used transverse leaf springs, as was then current on the G.P. racecars. Barcelona in 1954 proved the superiority of a coil layout on the Squalo Ferrari, and a complete switch was made on all Modena models.”

In 40-odd words, Ludvigsen wrote of experimental cars, the traditional transverse leaf springs used in most early Ferraris, and revealed the fact that it was at Barcelona that Ferrari finally determined that coil springs were more effective, thus placing them on all Ferraris henceforth. Ludvigsen tossed off this information like a Miles Davis jazz riff and crowned the articles with catchy titles such as “Seven Hour Stormer”, a reference to the lifespan of the Monza engine, or “Tiny Tornadoes from Turin”, an article about Abarths.

His technical fluency did more than generate interest among sports car racers, historians and engineers. For some of us, growing up with Ludvigsen was an invitation to learn and deal with mathematics.

VeloceToday’s editor looks at

the same car at R/A, 1960.

My father, who would bring the latest copy of SCI home every month to share with his ten-year-old son, was able use Karl’s articles as a means of teaching me how to figure out capacities, swept area, gear ratios, pound-feet of torque, and to do the figures in both Metric and U.S. measurements. Math may have been boring, but when applied to the understanding of Ferraris it became interesting and exciting. For the next few years SCI, eventually under the editorship of Ludvigsen himself, blossomed. Things changed when Karl left the magazine after renaming it “Car and Driver” and the new magazine lost its technical pre-eminence. He left, believe it or not, to be a PR man for General Motors. He later fielded executive posts at both Fiat and Ford, the latter taking him to England. Karl kept on writing, concentrating on books (four dozen to his credit), articles for Automobile Quarterly, and doing free-lance work for a number of other magazines.

His books–among them the acclaimed Porsche history, “Excellence was Expected”– earned him three Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot Awards from the Society of Automotive Historians and two Montagu Trophies awarded by the Guild of Motoring Writers. Along the way he founded the Ludvigsen Library in London, now in Suffolk, a post from which he still holds court. Check him out at www.karlludvigsen.com.

Almost thirty years after those days of learning math courtesy of my father and Karl Ludvigsen, I had the sheer audacity to suggest an article about Moretti to the editor of the new “Automobile Magazine.” Dave Davis, who was also the ex-editor of “Car and Driver”, having taken that position one editor removed from Karl Ludvigsen. Davis agreed and put me in contact with my mentor who owned the only restored Moretti 750 coupe around. Karl would call from London, and discussed the scope of the article and provided historical details while I scrambled on the other end somehow to record his words for posterity. I learned firsthand what I had realized before–that Karl was a perfectionist and demanded that every detail be accurate and complete. It was another lesson learned. The article thankfully, came out well.

Today, I am still learning from Karl. Reviewing his book, “Red Hot Rivals.” I discovered more than a few new bits of information. Karl presents the now-well known subjects of Maserati and Ferrari with detail and depth only a master such as Ludvigsen can handle. A good example is the chapter on the Ferrari 375 F1 versus the Osca V12. Ludvigsen, still the engineer, goes to the workshop where an engine is being restored and takes photos of the Osca’s components including its fork-and-blade connecting rods which allow two pistons to employ the same crank journal by using the fork rod as a journal itself. If not unique, the arrangement is highly unusual and a good example of the intuitive engineering skills of the Maserati brothers. Ludvigsen even arranges to weigh the parts and tells us why they were problematic.

That’s but one example that I found throughout the book which made it so enjoyable.Just when you think you know it all, there is Ludvigsen…thank God.

Very well written Karl Ludvigsen article Peter. Nice job. It motivated me to reread my old copies of Sports Cars Illustrated.

Hi Pete,

Two points:

1) The SCI cover identified as the “Edgar Team” shows the Edgar transporter (one of the first such) at Road America June 1957 but the cars parked beside it are

#6 E. Lunken’s 0658 and #75 is J. Quackenbush’s 0634.

2) The fork and blade connecting rod was an old design that was very common early in the history of automobiles. As engines became more powerful and rotated at highter rpm its faluts became more evident and manufacturers dropped it during the 1920s and 30s.

Regards,

David

Pete-

Kudos on this latest issue. Good variety and topics of interest. I have a couple of comments.

First, I’d like to reinforce your comments on Karl Ludvigsen. Several years back I was researching a topic and needed photographs. I visited the Karl Ludvigsen Library in London and was graciously hosted and tolerated there as I plowed through book after book of photographs in a room provided for such occasions. What an absolute treat as the library is fantastic. But the real treat was when Karl came into the office and he looked into the room and asked if I had what I needed, etc. A conversation ensued that ended up in his office, and I found him to be very friendly and engaging and more than willing to share time with someone he didn’t know but who showed an interest in automobiles and racing. I’ve been fortunate to meet many journalists and would have to say that he’s one of the best, not only from the viewpoint of his books, but his personal attributes. I would suggest you change to the title of your piece to “Karl Ludvigsen: His Excellence is Expected and was Delivered.”

My other point is in reference to the review of the Kudvigsen-Mailander book reprinted in this issue. You mentioned that Ferrari by Mailander is certainly the best photojournalism book we have ever seen and went on to mention three other books with similar credentials that come to mind– Klemantaski on Ferrari, and Ferrari, 1947-1953 and Marzotto’s The Red Arrows. I would like to add a book to that list. It’s by Frenchman Maurice Louche and is titled, “Emotion Ferrari–Europe 1947-1972. It’s another Wow! book of 504 pages filled with over 1,000 photographs of Ferraris racing in Europe from 1947-1972. These are rare photographs with few being published before. I picked it up to thumb it when I received it for a review in Prancing Horse and put it down some two hours later. There’s a chilling, emotional photograph on one of the first pages of Enzo, son Dino and driver Righetti in the Maranello factory yard in from of a 125 S that had just brought Ferrari its first racing victory in the Grand Prix of Rome on May 25, 1947. I would offer that this book should be on the bookshelf of anyone who considers themselves a tifosi or Ferrarista.

Keep up the good work. I look forward to recieving an new issue each Wednesday. If you want to publish any parts of this email, feel free to do so.

Regards-Jeff Allison

Pete,

I am moving some ink from Brazil… and we are specially thankful to Karl, first by his worldwide launching of our PUMA sports car in the 70’s (I was chief engineer there) after by the amount of great books that really impressed automotive enginers and specialized journalists too.

Regards,

Ronaldo Brochado