By Peter Darnall

Imagine yourself a passenger in a Type 57SC Bugatti Atalante. The view through the windshield is stunning: a long tapering hood framed by delicately arched fenders. The snug interior of the coupe cabin fills with the incredible sound of the 8-cylinder Bugatti engine at peak revs as the siren-like scream of the supercharger adds its surreal note. The tree-lined scenery flashes by faster and still faster. The sensory overload is intoxicating.

Such was my introduction to the inner sanctum of the Bugatti mystique.

I was about fifteen years old at the time of that ride. My initial exposure to exotic European automobiles had taken place the previous year at the sports car races in Golden Gate Park, which were held in late May 1952. This event whetted my appetite and I was eager to learn more. Ken Purdy’s eclectic book, Kings of the Road, became my favorite source of information. Purdy was an unabashed Bugatti enthusiast and he could write!

Although I could recite many of Purdy’s anecdotes from memory and tended to prattle on about Bugatti nomenclature, I had never actually seen nor heard a Bugatti in person; I could talk a good Bugatti, but that was about it.

Doctor George Kerrigan, a Bay Area orthodontist and noted automobile collector, often drove over the hills from his Orinda home, accompanied by his wife, to visit her parents, who lived next door to us in Berkeley. One day Dr. Kerrigan showed up with an elegant Type 57SC Bugatti and, after delivering his wife to her parents, offered to take me for a ride. We drove out The Arlington and meandered through the Berkeley Hills until we reached Tilden Park. Once past the Berkeley city limits, he put his foot down and the Bugatti came into its own: the mailed fist hidden in a velvet glove.

“The mailed fist hidden in a velvet glove” A Type 57 Bugatti at a Watkins Glen Concours d’Elegance c.1951-52. Photo courtesy Harold Lance.

The Type 57 was a new design created by Jean Bugatti, son of founder, Ettore. Incorporating the mechanical genius– skeptics might say quirkiness- of the previous Bugatti race cars, the Type 57 added hauntingly beautiful styling to create the world’s first supercar. My soul-stirring ride in the Bugatti became the standard by which I judged all sports cars; nothing of more recent vintage has even come close to the visceral excitement of that Type 57 Bugatti.

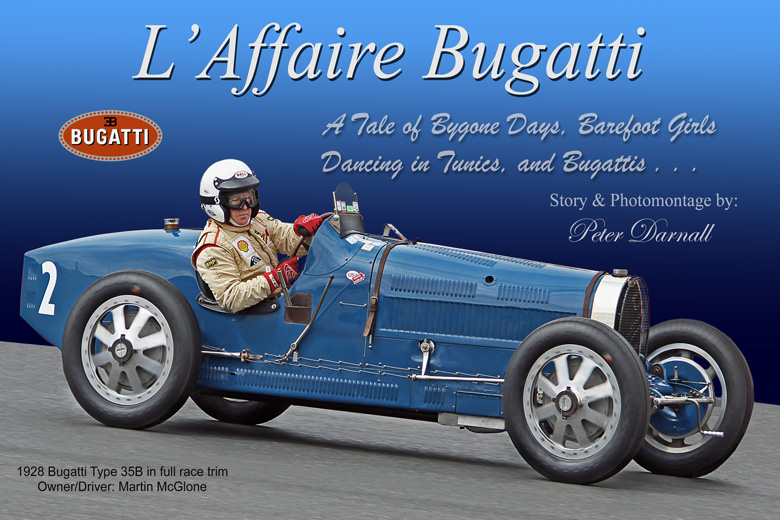

As a student In Berkeley High School, I participated in creative writing classes. Not surprisingly, the subject of my writings often pertained to race cars—with a strong preference for the Type 35 Bugatti machines. The Type 35s were extremely successful, winning over 1000 races in their day. One essay, which was primarily about the Type 35 with its distinctive cast aluminum wheels, also mentioned the tragic death of Isadora Duncan.

Isadora Duncan was an iconic figure of the 1920s who had become internationally famous for her Interpretative Dance techniques. On September 14, 1927, Isadora met an untimely end as a passenger in an open sports car near Nice, France. As the car accelerated away from the curb, her long, flowing scarf became tangled in the spokes of a rear wheel and she was partially decapitated. While the car may have been a Type 35 Bugatti, many feel it was more likely an Amilcar, possibly the CGSS model.

We were encouraged to exchange our essays with other students in the group for their criticisms and to use their critiques to improve our original works. One girl who read my piece, happened to be a student at a unique dance academy in the Berkeley Hills. This institution, which specialized in the teachings and dance techniques pioneered by Isadora Duncan, had been a Berkeley tradition for many years. She had fixated on the reference in my essay to the famous dancer and, assuming we shared an interest in the subject of dance, invited me to participate in an upcoming celebration to be held at the Temple of Wings.

My fascination with Bugattis was about to take me into unfamiliar territory.

The Temple of Wings is a Berkeley landmark. The original building was a structure consisting of a thirty-four Greek Corinthian style columns surrounding two porches. The open air configuration allowed the Boynton family to follow their Bohemian lifestyle and also provided an amphitheater for dance activities.

Florence Treadwell Boynton, a lifelong friend (and possibly a half-sister) of Isadora Duncan, had created the structure both as a home and as a dance academy dedicated to promoting Isadora’s teachings. When Isadora was in the Bay Area, she would often stay with the Boyntons and put on dance performances for the neighbors.

The original home was destroyed in the Berkeley Hills fire of 1923, leaving only the concrete columns standing. A new structure was built, incorporating the columns and amphitheater, but adding the walls and roof of a conventional home. Sulgwynn Quitzow, Florence’s daughter, continued the tradition of the dance academy accompanied by her husband Charles.

As a result of my Bugatti essay mentioning Isadora Duncan, I eventually found myself standing in a reception line at the Temple of Wings, preparing to meet Sulgwynn Quitzow. My date for the evening was the girl who had read my paper and had invited me to join her for the festivities. At the time, I knew nothing about Interpretive Dance—I still don’t to this day. I felt badly out of place and mentioned this to my date. “Relax,” she assured me, “just act normal with Mrs. Quitzow and everything will be fine.”

The line advanced quickly and we were soon standing in front of Sulgwynn Quitzow. “How did you became interested in Interpretive Dance?” she asked. As I struggled to find words to answer, my date cheerfully mentioned that I had written a paper about Isadora Duncan. “Well now,” Sulgwynn enthused, “Please tell me more!”

I prattled on reciting Ken Purdy’s colorful prose on Bugatti eccentricities until Sulgwynn put up her hand. ”Most interesting,” she said, “Welcome to Quitzow’s.” Then, in a quieter voice, she added, “We’ll speak later.”

The ambiance of the unique home was enticing; the presence Isadora Duncan and her artistic legacy subtly blended with the Beaux Arts style of the Temple of Wings. The dancing exhibitions, which took place in the outdoor theater, cast an almost hypnotic spell over us. The evening fog softened the starkness of the Greek columns while the stage lights enhanced the graceful movements of the barefoot dancers in their flowing tunics. The performances seemed timeless . . . we might have been in the Theatre of Dionysus in ancient Athens. While I knew nothing of the art of dance, I was mesmerized by the experience.

Following the dancing exhibitions, Sulgwynn took us aside and, as we sat in another portion of the large home, she urged: “Now tell me more about Bugattis.” I must have chattered on at some length, but she seemed genuinely interested. She confessed that she knew nothing about cars, but had heard the name Bugatti mentioned in past conversations with her mother and Isadora Duncan. I was, she admitted, the first person she had met who knew what the name Bugatti meant.

I was to attend several more parties at the Temple of Wings before leaving for college. My name had been added to a special list of “guests” and Sulgwynn always found a few minutes at these events to share our thoughts on bygone days in Berkeley, the legacy of Isadora Duncan and, of course, Bugattis. She now referred to me as her “Bugatti Man.”

High praise indeed!

Wow. Those kinds of connections (“coincidences” to some) make me think there is a God.

Stunning story, I hope to see more. Much too short! LOVE those old Bugatti! The car shown and its moniker “Mailed Fist / Velvet Glove” is so …cool, for lack of a better term! (Hope everyone who reads the above essay realizes its meaning; “mail” = chainmail = brass knuckles in a velvet glove)

Can one see this landmark or is it gated off like everything else worth seeing in California?

-A8Tomic