Story by Peter Darnall

“Please don’t call this car a replica. It’s a Lagonda!”

‘Lagonda Joe’ Harding was describing his 1939 red Lagonda Le Mans sports racing machine recently. Joe earned the nickname ‘Lagonda Joe’ years ago for his involvement with both the creation and the racing of these unique Lagonda machines in England. He makes an interesting point: The word “replica” conjures up mental images of shoddy fiberglass contraptions or of clandestine attempts to convert an automotive sow’s ear into a silk purse. These Le Mans Specials are, as Joe stressed, Lagondas to the core. They were built on a production chassis and used period-correct Lagonda components—which is exactly what the Lagonda factory did when they made the original Le Mans specials in 1939.

The Lagonda Company, as well as Lagonda owners, had a penchant for crafting lightweight specials from production Lagonda models back in the day. These ‘specials’ took on all comers on the race tracks of the world and scored a number of extraordinary victories. Of course, this strategy only works if your base production models are fast to begin with.

And Lagondas were quick; Famed Italian driver Tazio Nuvolari once gave a Lagonda Rapier the ultimate accolade when he described the diminutive British jewel as “a small Alfa.”

The Lagonda company was founded in 1899 by American expat Wilbur Gunn. He chose the name Lagonda, which is a Shawnee Indian name for what is now Buck Creek near his hometown of Springfield, Ohio. Gunn had come to England to further his career as an opera singer but returned to his mechanical roots when his musical ambitions floundered. The Lagonda company, located at Staines, Middlesex, had some success with motorcycles and introduced its first automobile in 1908. Wilbur Gunn died on September 27, 1920, but Lagonda automobiles continued to improve, gaining favor among wealthy sporting motorists of the day.

Stemming the Red Tide at Le Mans

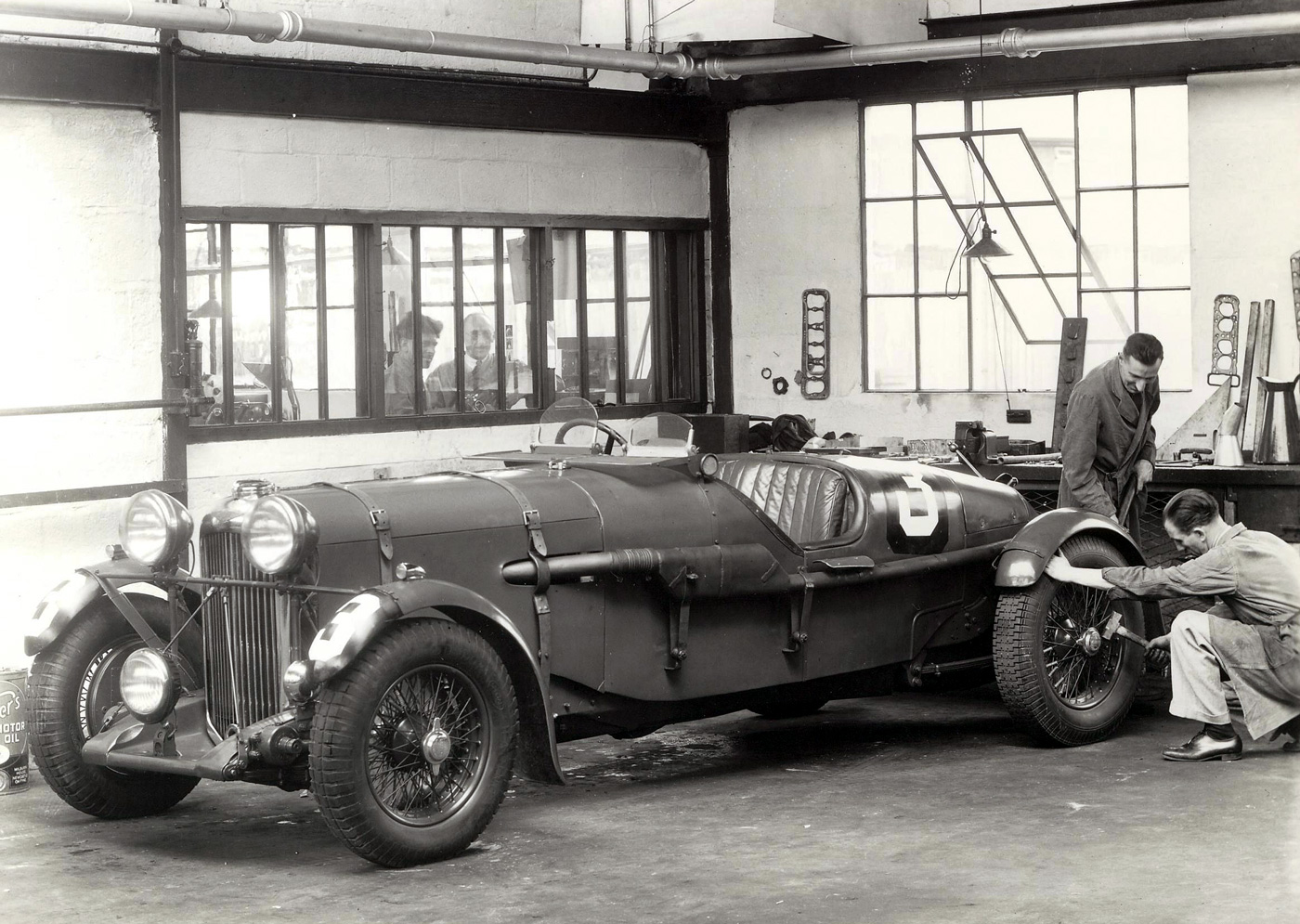

A lightened TT version of a production M45 Lagonda Rapide, was created by the team of Arthur Fox and Charles Nicholl, who were known for their tuning expertise on the Meadows 4 ½-Liter engine. Fox & Nicholl prepared three Lagondas for the 1934 RAC Tourist Trophy at Ards. The cars were so impressive that the Lagonda Board of Directors decided to enter two M45 team cars in the 1935 24-Hour endurance race at Le Mans. The Lagonda driven by Johnny Hindmarsh and Luis Fontés won a huge victory that year, breaking a four-year string of victories at Le Mans by Alfa Romeo. The win brought fame to Fox & Nicholl, which was now essentially the Lagonda works racing team.

All was not well financially at Lagonda, however, and the company fell into receivership in 1935. Lagonda was salvaged by entrepreneur Alan Good, who outbid Rolls Royce and reformed the company as LG Motors. In 1936, a series of four light-weight competition Rapides, powered by the venerable 6-cylinder engine, was turned over to the Fox & Nicholl team. One of these specials, Chassis/Engine Number 12111 (later registered EPE 97), would go on to establish an extraordinary record, including a win at Le Mans in 1935, and is regarded by many as the most famous Lagonda of them all.

The Great Depression had taken a heavy toll on the British automobile industry. Walter Owen Bentley had lost control of his namesake company, which had been taken over by Rolls Royce. Alan Good persuaded Bentley to leave Rolls Royce and join Lagonda as technical director, hoping to infuse Bentley’s legendary sporting flair into the revamped Lagonda offerings. The exodus from Rolls Royce continued as engineers Stuart Tresilian and Charles Sewell followed Bentley to Lagonda. Alan Good had scored a major coup at Rolls Royce’s expense and now had the talent on board to revitalize Lagonda

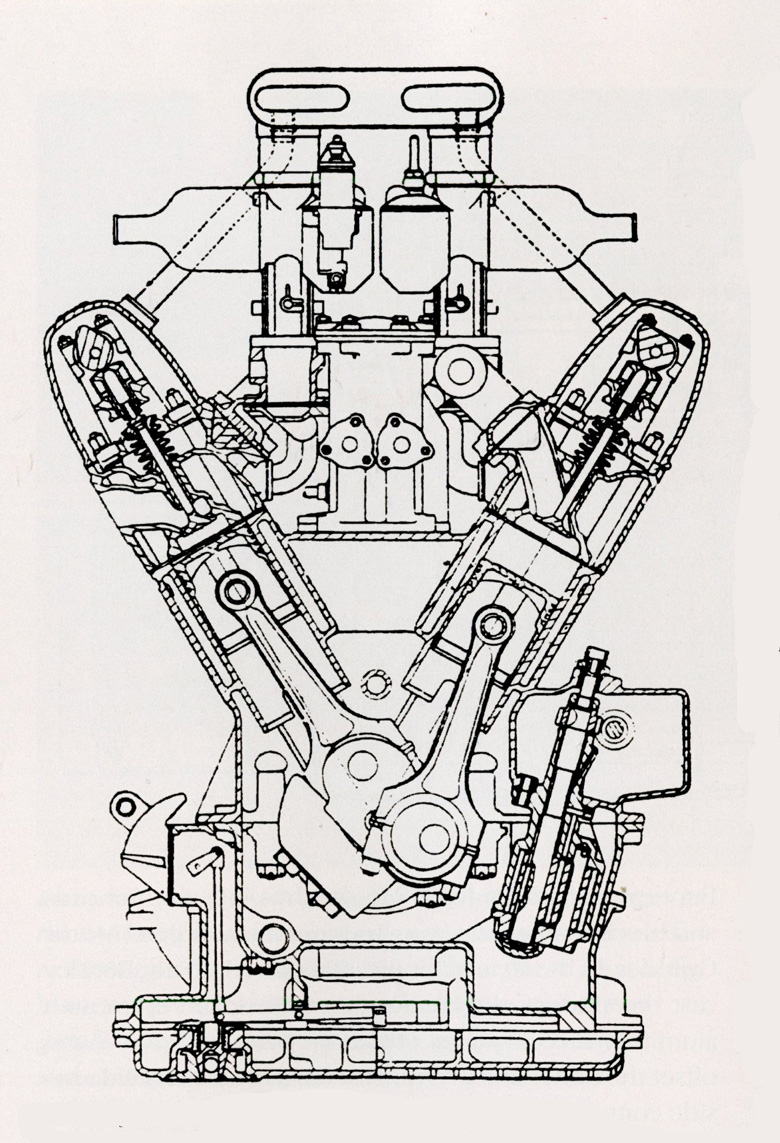

Working conditions were primitive at Lagonda—now little more than a collection of rickety sheds. Bentley complained of rain water dripping from a leaking roof which threatened designs on the drafting tables. Nonetheless, he and his team buckled down and produced a remarkable short-stroke V-12 engine, which was intended to power the top-of-the-line Lagondas. Shortly before Christmas 1938, Chairman Good announced a bold commitment to promote the new engine: Lagonda would enter a car powered with the V-12 engine in the upcoming 24-Hours of Le Mans.

Bentley objected to Good’s proposal. He argued that less than six months remained until the running of the French classic. The V-12 engine was never intended to withstand the rigors of endurance racing and there wasn’t enough time to develop a competitive endurance racer. W. O. Bentley knew whereof he spoke: A Bentley won overall at Le Mans in 1924. Bentleys won again on the Sarthe circuit every year from 1927 to 1930—a total of five wins in all.

Diagram of W. O. Bentley Designed V-12 engine. From Karl Ludvigsen’s excellent book “The V12 Engine.”

Alan Good prevailed. Work would begin immediately to prepare a car to run at Le Mans. At Bentley’s insistence, however, strict limitations would be imposed. Rather than develop a prototype, the company would save time by creating a lightened version of a standard production model. The venture at Le Mans would be a familiarization run; if the results were encouraging, Lagonda could return to the Sarthe circuit the following year with a proper effort.

The project car, chassis number 14089, was assigned the number 5, which was the Le Mans registration number. Good’s choice of driver, Richard Seaman, had not materialized due to contractual conflicts with Mercedes Benz. ERA star Arthur Dobson was named in place of Seaman. Brooklands habitué Charles Brackenbury would be the co-driver.

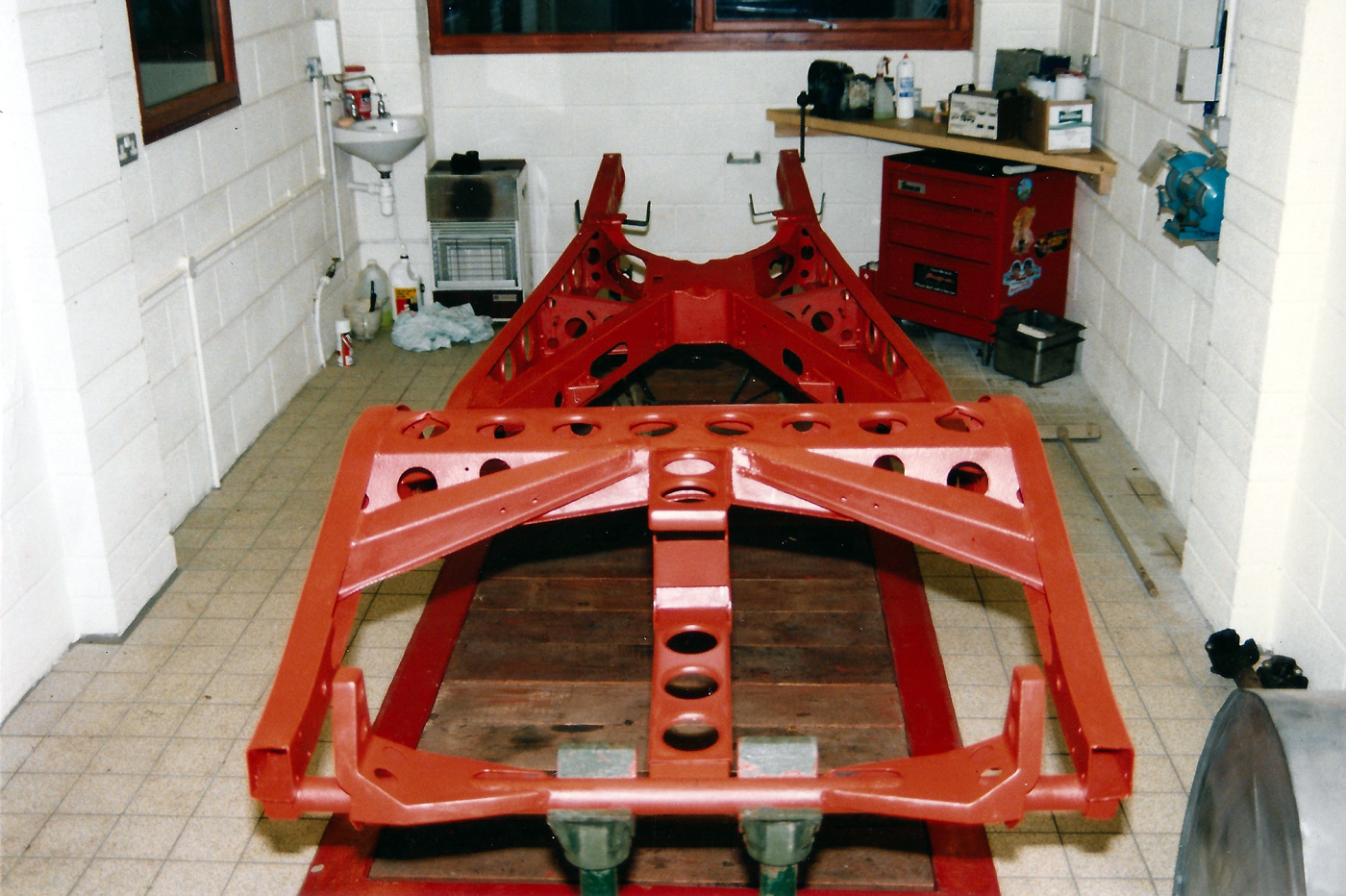

A standard 10-foot 4-inch short-wheelbase chassis was formed out of narrow gauge steel. This frame was extensively drilled with holes to further lighten it. Finally, a beveled edge was laboriously added to finish each hole. Joe Harding recalled creating a special tool to make that bevel. As he pointed out, the bevel was essential. The lightened chassis would not have coped with the forces imposed by the V-12 without it.

Bare Chassis of Joe Harding’s Le Mans Special – Note extensive drilling and bevel finish on holes. (Credit Joe Harding)

By March 1939, Bentley had a V-12 engine fitted with four carburetors running on a bench test. The engine was producing 206 bhp at 5500 rpm. Word of the project had spread among the Lagonda inner circle. Peter Mitchell-Thompson, recently acceded to the title of 2nd Baron Selsdon, requested to purchase a second car and join the Le Mans effort. Good eagerly accepted the offer and Lord Selsdon’s friend, William George Hood Walrond, 2nd Baron of Waleran, was named co-driver. The two Lords would drive Lagonda #6 (chassis number 14090) at Le Mans.

The running gear used production Lagonda components which were drilled for lightness wherever possible. The six large holes in each brake drum were covered with thin sheet aluminum to prevent unwanted rain water or debris from entering. Noted Lagonda designer Frank Feeley drew the plans for an ultra-lightweight body which would be constructed in five major sections and hand-beaten from aluminum sheet. The panels would attach directly to the chassis using quick release fasteners or simply be wired in place. Feeley’s stunning creation had one purpose: to survive the twenty-four-hour ordeal. The distinctive coachwork was never intended to be used on a production Lagonda.

Lagonda LG 45R (Chassis Number 12111) built for Fox & Nicholl before start of 1937 Le Mans race. (Photo courtesy Lagonda Club)

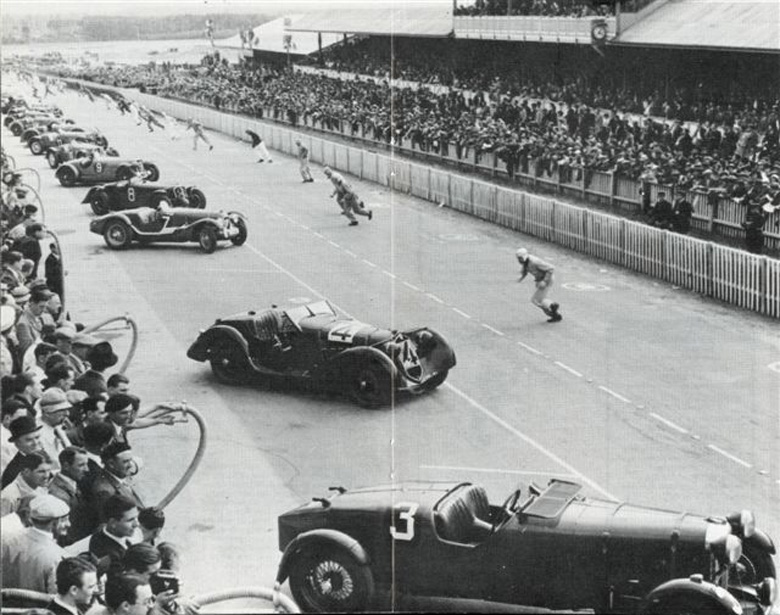

On June 7th, only the works #5 car was available for an unveiling ceremony and a brief testing session. Even then it wasn’t complete. With the race at Le Mans scheduled for June 17-18, time had nearly run out. The two Lagondas would have to be set up and tested on the drive to Le Mans. Fine tuning on the cars would be done right up to the actual start of the race.

The Lagondas ran exactly as planned, respecting the conservative conditions imposed by W. O. Bentley. His directive instructed the team to maintain an average speed of about 1 mph above the previous year’s winner and to avoid any competitive shenanigans. The only mechanical issues encountered during the race were minor: a sticking clutch and a broken exhaust bracket-both glitches were corrected during routine pit stops. When the checkered flag dropped, the works #5 Dobson/Brackenbury car had completed 2,006 miles at an average speed of 83.61 mph— taking an incredible first in class finish. The Selsdon/Waleran car followed immediately behind, finishing second in class. The two Lagondas, which had finished in third and fourth places overall, were beaten to the finish only by a supercharged Bugatti Type 57G “Tank” and a Delage D6 3L, both highly specialized endurance racing machines. A protest had been lodged against the Delage for using methanol, but the protest was disallowed by the French scrutineers. Bentley later calculated that the Bugatti’s winning average speed was 86.8 mph and that Brackenbury, driving within limits, had lapped at 86.78 mph during his shift.

Lagonda Number 12111 at Brooklands during the BRDC 500 Mile event in 1936.(Photo courtesy Lagonda Club)

After the race, the two Lagondas were unceremoniously loaded up for the return trip to the Lagonda factory at Staines, where they received a hero’s welcome. Bentley and his team at Lagonda had worked against time to transform a production automobile, originally conceived as an elegant sports-touring car, into a pukka long-distance endurance racer. They had taken on the best in the world and cleaned house at Le Mans. Old Number 5 and Number 6 Lagondas were now British motor racing icons. Bentley’s payback for his shabby treatment at Rolls Royce must have been especially sweet.

How fast were these Lagondas?

Lagonda Joe Harding opines that they could well have won overall at Le Mans in 1939. had they not been restrained. They certainly would have been the cars to beat the following year, he concluded.

There would be one more outing for the Lagondas. This time there would be no restrictions on their performance. The race would be the August Bank Holiday handicap event at Brooklands on August 7, 1939. Charles Brackenbury edged out Lord Selsdon to win by 3.8 seconds at an average speed of 118.45 mph. Incredibly, Brackenbury had turned in an unofficial lap at 140 mph during a practice session!

Although no one knew it at the time, this event would be the last held at the venerable Weybridge facility. The outbreak of the Second World War brought a close to all automobile racing. Lagonda would not return to defend its honors at Le Mans.

Lagonda Joe Harding knows the Lagonda marque and the story behind the magnificent 1939 Le Mans effort as well as anyone. He stressed that the re-creations of the two original factory specials were painstakingly assembled by Lagonda owners and enthusiasts using Lagonda components. The cars chosen for this exercise were often in poor condition or had been involved in a wreck. There was never any attempt at subterfuge.

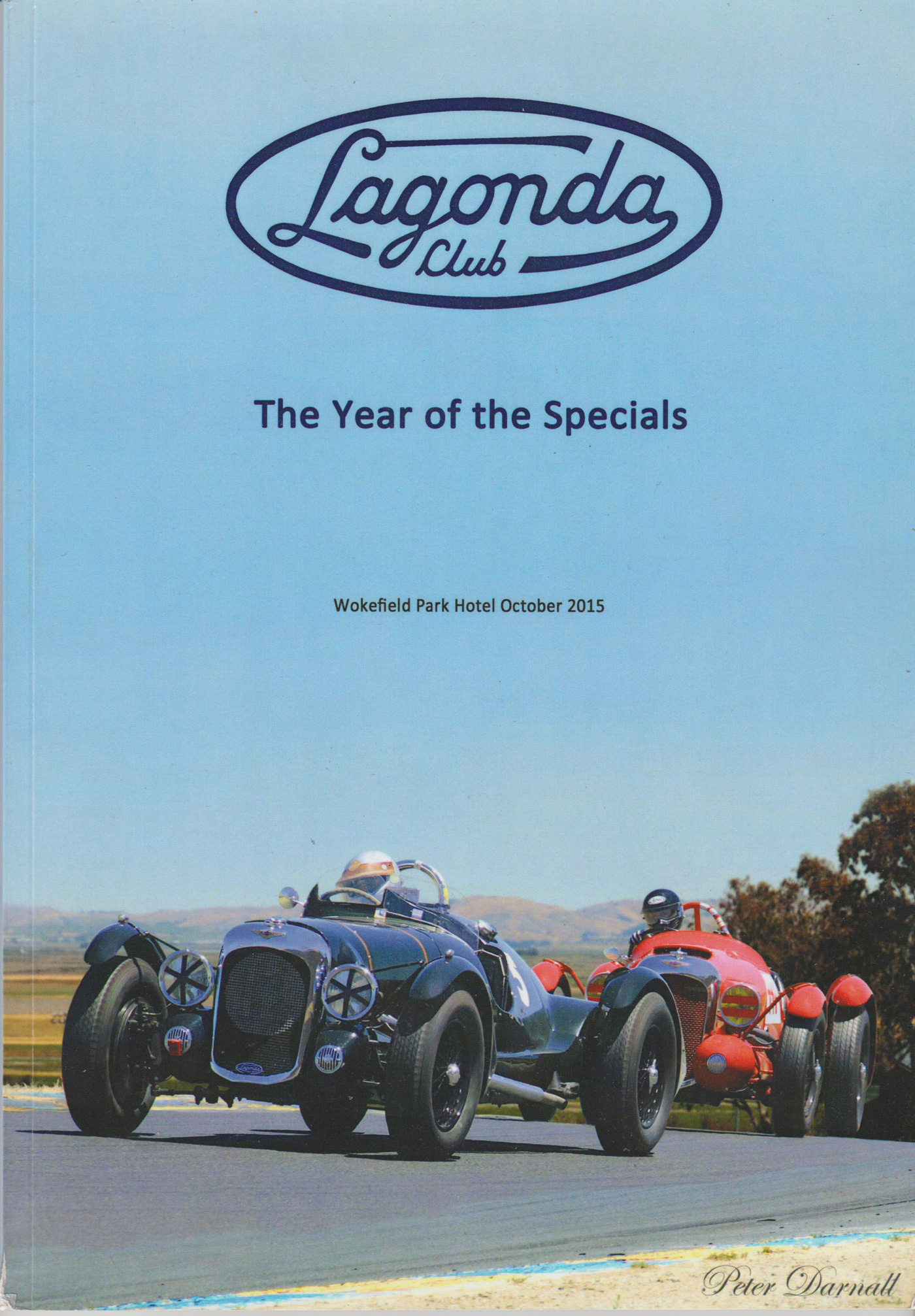

The Lagonda Club, Ltd. recognizes these unique machines as Lagondas and recently published a book entitled “The Year of the Specials” to honor these creations. That’s my photograph on the cover showing Richard Morrison leading Joe Harding at a recent vintage racing event.

Yes, Joe, these are Lagondas!

What happened to the two Le Mans Lagondas? Stayed tuned…Ed.

I recall there was a Lagonda V12 in the 1950s when the name/company had been acquired by David Brown of Aston Martin. Presumably this was the same engine as that of the VeloceToday article?

I recently visited a shop in England that’s restoring a V12 Lagonda. They learned that when that engine was first built, the cam profile was incorrect, due to a drafting screwup in the design office. When the error was discovered and corrected, there was a HUGE power increase. I don’t know if this happened before or after the Le Mans successes. Either way, it was quite an engine.

Thank you for a delicious article. I’ve loved Lagondas ever since I learned they had Meadows engines, similar to that of my father’s 1928 Invicta (“It goes or I go,” my mother told him, and only she remained.)

Paul Wilson

You raise an interesting point, Paul. According to ‘Lagonda Joe’ Harding, the cam profile wasn’t the issue; valve springs of the day were a weak point and prone to failure. W.O. Bentley’s V-12 engine was intended to turn continuously higher rpm than any other engine of that era designed to run for 24 hours.

Joe’s Lagonda, which is fitted with modern valve springs, is raced in vintage events and, according to Joe, has not experienced any valve spring failures although he regularly turns 6,00 rpm shifting from second to third.

Yes, this was quite an engine!

An excellent article but there some tiny errors. Fox & Nicholl:- It was Bob Nicholl, notCharles. The 1935 Le Mans entry was by Warwick Wright. The factory was in Receivership at the time. EPE 97 did not exist in 1935, so could not enter Le Mans. The 1935 winner was BPK 202. The Brooklands refuelling picture has been coloured in from a black and white photo. The car was bright red, not green.

Paul Lindsay,s query: No, the 1954/5 V12 engine was entirely different.