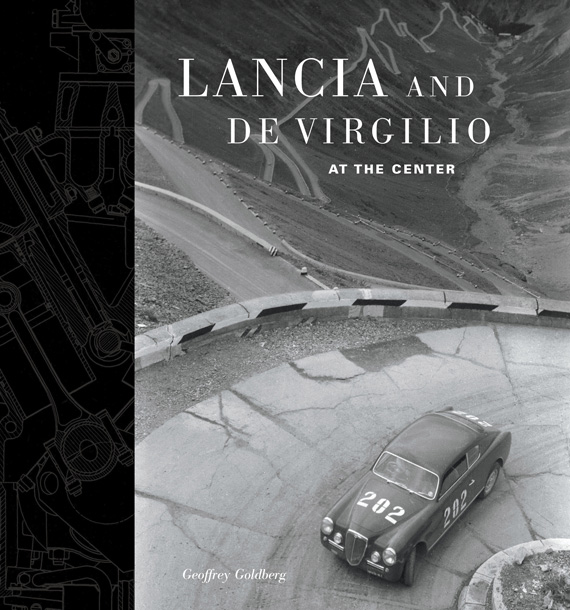

Title: Lancia and De Virgilio: At The Center

Author: Geoffrey Goldberg

Prefaces: Luigi De Virgilio, Miles C. Collier

Format: Hardcover, 10 ¾” by 11 ½”, 332 pages

Photos: 240 black-and-white and 39 color photographs; 231 illustrations

Footnotes, Index, Bibliography and Appendixes

Retail Price: $99.95/£65.00/€80.00

ISBN-13: 978 1 935007 25-8

To order, call 602-852-9500, (800) 831-1758, or visit www.bullpublishing.com

Review by Nigel Trow

All photos courtesy Geoff Goldberg/David Bull

I met Francesco De Virgilio occasionally during the 1960s and 70s, mostly in Turin, but for the last time at Mugello in 1981, during the Vincenzo Lancia Centenary celebrations that I helped to organize. He was a warm and friendly man of great charm, an engineer, a musician and an easy conversationalist full of fascinating stories about Lancia during the previous 40 years.

Geoff Goldberg’s illuminating book, Lancia and De Virgilio: At The Center, fleshes out those conversations wonderfully, providing an unusually intimate portrait of the man and the company during the last decade of Lancia family ownership. This is the proper stuff of history, which always concerns human activity and its consequences.

Unfortunately, automobile historians have generally overlooked this simple fact, from the beginning their emphasis lying with the machine or the race, and making scant reference to context or biography. Charles Jarrott, for example, who wrote Ten Years of Motors and Motor Racing in 1906, offers no sense of those turbulent complexities surrounding the European races described. He tells a great personal, Boy’s Own, tale that reveals little about himself, the cars or other drivers – despite a chapter on Racing Motorists I Have Met – and in many ways set a pattern for years to come. There are exceptions, of course. Anthony Bligh’s George Roesch and the Invincible Talbot and The French Sports Car Revolution, are admirable books, as is Robert Lacy’s Ford, Walter Henry Nelson’s Small Wonder, Brock Yate’s Enzo Ferrari and Horst Monnich’s The BMW Story. Together with a few others such as Nunzia Manicardi, these writers set people and machines in particular worlds, broadening our view of all three.

Behind one of those upper windows was my desk and my drafting table, on which I drew all Aurelia engine, from the 538 to the famous B10. After that came the B21, the B20, the B12, the Spider America, and so on -- Francesco De Virgilio

That serious historians should continue to neglect the examination of what Miles Collier describes in prefacing Goldberg’s book as “quite simply the most important technological object of the 20th century”, remains a source of frustration for scholar and general reader alike. Happily, this newest addition to Lancia literature offers not only significant insights into the company itself, but is an example of how the whole field of automobile history might be re-vivified.

It begins with people, with charming, beautifully printed pictures of the deeply Piedmontese Lancia family absorbing a young Calabrese engineer, Francesco De Virgilio, through his marriage to Rita, niece of Vincenzo, the company’s founder. In his masterpiece, The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa described the Piedmontese and the Sicilians as the most punctilious in Italy. Born in Reggio di Calabria, on the Straits of Messina, De Virgilio had grown up so close to Sicily as to immediately appreciate the warmth and courtesy with which he was received in Turin, and which he continued to enjoy throughout his life. Joining Lancia as an engineer in 1939, he married Rita in 1947 and retired from the firm in the summer of 1975, though continuing as a consultant to the racing team until 1984. However, despite becoming a member of the Lancia family early in his career, he was never privileged, achieving his importance to the company through the creative inventiveness and competence meticulously documented by Goldberg.

In concentrating on a single, previously unsung engineer and his lifetime’s work for an historic Italian motor manufacturer, this beautiful book emphasizes the place of the personal in industrial life. Particularly in Italy, despite the security of a job with a pension being highly desirable – but the monotony of the production line being less so – various forms of small

to medium size family firms have demonstrated an individual inventiveness that is still admired ( though seldom imitated by global business ). Frequently paternalist until recently, individual initiatives made discreetly and within the rules have had their place. Although now disappeared in the wake of corporatism, sociable practices like the Maserati brother’s habit of daily taking lunch with their workforce in a Pontevecchio restaurant were not unknown beyond Bologna, and could still be found at the end of the 1990s. These made for the easy interchange of ideas (and grumbles), and a similar lightness characterized the early Lancia factory. Although by De Virgilio’s time the company had grown too big for such intimacies the underlying family ethos remained, encouraging his sometimes brilliant engineering insights as wholly in keeping with the firm’s innovative reputation.

The best known of his many achievements was the successful balancing of the V6 crankshaft, a tale Goldberg tells with the enthusiasm of a lifelong Aurelia owner. He also proves to be a generous author, as the inclusion of John Cundy’s succinct technical account of this matter ably demonstrates. Incorporating this engineering essay, written in layman’s language, is characteristic of the fluid format of the book, which moves out from a conventional linear time line to a more relational pattern where differing aspects of De Virgilio’s life and work come together outside the chronology. This does not always succeed, though. The book opens with his marriage, made visually memorable by a magnificently reproduced photograph of the couple seated before the altar of Turin’s Gesu Nazareno church, but family life itself is left to the end, as an epilogue. Why? The section is far more that an afterthought, the photographs being utterly human and beautiful, especially the picture of Rita, taken by Francesco himself, on page 266 ( De Virgilio was a fine photographer. Not quite in the same class as Nuvolari, who was truly brilliant, but more that an amateur snapper). The text expands these family pictures, and I wanted more.

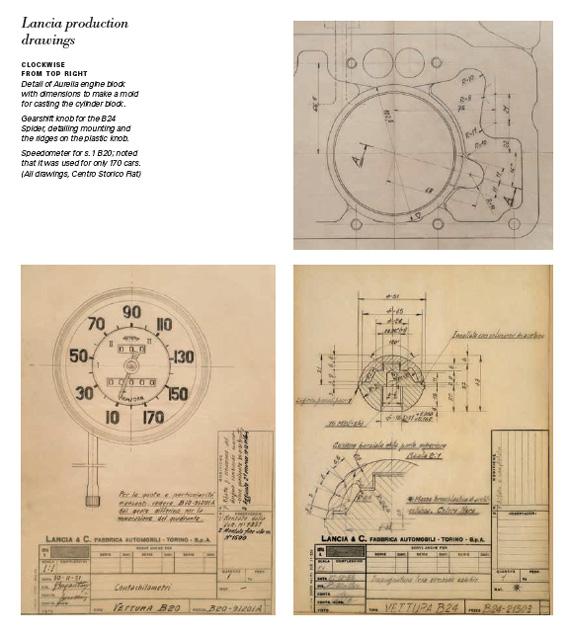

Nevertheless, Lancia and De Virgilio is a distinctive labour of love framed by scholarship. It is particularly distinctive in its generous use of De Virgilio’s sketches, workings-out and correspondence, which, coupled with fine reproductions of factory engineering drawings extend the readers understanding and pleasure. Coverage of the racing period that began with Bracco’s redoubtable success in the 1951 Mille Miglia in the little 2 litre B20, and finished with the radical D50 GP car in mid-1955 is also exemplary in its fine use of photographs. The sheer volume of fresh and stimulating material gathered together by the author and his collaborators is remarkable, providing any serious student of automobile history with much to think about, and question. Some matters are glossed, however. The precipitate departure of Gianni from the scene following Ascari’s death at Monza on May 26th, when he crashed Castellotti’s Ferrari on one of the Lesmo curves just a few days after plunging his D50 Lancia into the sea at Monte Carlo, is not discussed. In the past the author and I have amiably disagreed about this, Goldberg believing that the accident had little to do with Gianni Lancia’s flight from the company’s looming fire sale (not bankruptcy, as quoted). There is no question but that the firm was deep in financial trouble by the mid-1950s, or that the costs of racing coupled with old fashioned production methods and high labor costs in the road car and commercial vehicle sections cited by Goldberg were all pointing to failure. But within days of the death of his lead driver, and after attending the funeral in Milan, Gianni left Genoa via the luxury liner Andrea Doria for Brazil in the company of his mother. However, although a troubled man with a collapsed marriage, a huge new office block to pay for, factories in urgent need of modernization and the responsibility for some 7000 workers around his neck, he also had an F1 car capable of beating the Mercedes, capital available outside the factory and a wealthy family, not all of whom wanted to sell up. In spite of telling a friend that he was fed- up and wanted to clear off to Brazil, had Ascari lived he may well have carried on with the racing plan and achieved the success that accrued to Enzo Ferrari; after all, one of his last executive acts at Lancia was to authorize Castellotti to take two D50As and an unofficial support team to Spa, for the Belgian GP on June 25th. Alberto’s needless death was a deep, traumatic shock to Gianni, and it broke his dedication to the family business. What did not break was his resilience and determination. How otherwise could he have built a substantial cattle ranch in Brazil’s Mato Grosso?

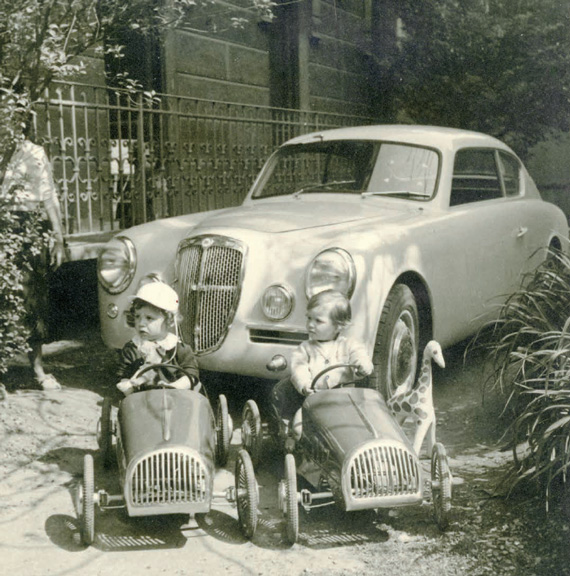

Caption from the book: A new B20 coupe was driven home by Terenzio Lancia for lunch with the De Virgilio family. In front of the car are young Luigi De Virgilio and his cousin Manfredi Lancia.

The question, however, remains speculative, and the cardinal strength of Lancia and De Virgilio – At the Center is the author’s clear determination to avoid such indulgence. The extensive, well laid out references are ample demonstration of his intention.

It would be optimistic to hope that many books such as this might be published in the future. The web’s offer of instant gratification is too strong, and e books give easy, inexpensive information. They never provide the pleasures of texture, weight and heft found here, however. Lancia and De Virgilio is for book lovers as well as petrol heads. If my own forthcoming book, Maserati – The Family Silver, shares half its qualities, I shall be a happy man.

About the Author

Geoffrey Goldberg has long been fascinated by Lancias. As an architect, he has appreciated Lancia’s independent approach to design and attention to detail for many years. His hometown of Chicago is similar to Turin, as both cities were once manufacturing centers, with inventive design and engineering central to their success. Goldberg has owned Lancias for more than 30 years, is active in the Lancia community world-wide, and has spent much time in Italy with the De Virgilio family and others close to the Lancia company.

About the Publisher

David Bull Publishing is dedicated to producing the best books in motorsports. Founded in 1995, the company has consistently won praise from readers and the media for the editorial quality and presentation of its titles. In 2011 János Wimpffen’s Elva: The Cars, The People, The History won the Motor Press Guild’s award for best book, and in 2012 Michael Argetsinger’s Formula One at Watkins Glen received a Gold Medal in the Transportation category in the Independent Publisher Book Awards.

Ordering

Lancia and De Virgilio: At The Center is available through specialty automotive booksellers, and directly from the publisher. To order please call 602-852-9500, (800) 831-1758, or visit www.bullpublishing.com. Readers can also follow us on Facebook for news about upcoming books and events.

For orders in the United Kingdom please contact Chris Lloyd Sales & Marketing Services, which distributes David Bull Publishing books, at (0) 1202 649930.

Thank you for a great review for a great book. I too like books that provide the human interest and detail that are an integral part of any story. I looks like I will now be purchasing a copy of Nigel Trow’s upcoming Maserati book also!

I appreciate you comprehensive review of a truly outstanding new book about De Virigilio and Lancia. Geoff’s scholarship in producing this book is brilliant, his depth of knowledge leaves very little to ponder about De Virigilio and his skill in design. The book flows well for those of us who may not have all the technical knowledge of a mechanical engineer designing and building motors. Well done Mr. Trow, your skill as a writer and reviewer are appreciated.

This is a very interesting book made even more so by Geoffrey Goldberg’s use of extensive footnotes which can lead you on to more and more. Excellent.

I just got the book as a gift from a good friend. Geoffrey Goldberg’s book is a wonderful and comprehensive artwork about an important part of the automotive history – bravo. In deed a great review by Nigel Trow, thank you.