A sophisticated faux-Ferrari found at Hershey. Photo by Brandes Elitch.

Left without many choices, thousands of sports car enthusiasts in the early 1950s were forced to improvise their own two seat roadster or coupe. Preferably, it would look like the best of Italy, as seen in the pages of Road & Track magazine or on the tracks of Watkins Glen or Pebble Beach.

Post war America was the home of the automotive DIY–an acronym for Do It Yourself. With plenty of room in suburban garages, great tools from Sears, a nearby junkyard, and an amazing new material called fiberglass, thousands of young guys knew that even if they couldn’t afford a Ferrari, they could probably build one.

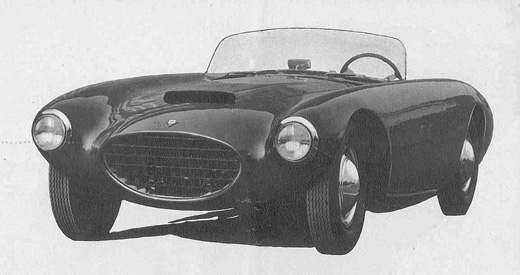

Dick Jone’s Ferrari-like creation.

America, it seemed, was head over heels in love with sports cars. For a generation raised on Ford Model Ts and Model As, working on cars came naturally, whether raised on a farm or in the city. De-coking a head was as commonplace then as installing a new set of sparkplugs is today. In a day long before government regulations, it was very possible to build yourself a car–even one designed from scratch. Most American V8 engines, even in the early fifties, were more than a match for their smaller but more sophisticated European counterparts, so the power was there. Chassis and suspension were another matter, but for a boulevardier, it was not a big problem. Within a few years, there was huge variety of custom fiberglass bodies to choose from. Without a doubt, the most famous and probably most successful was the Devin fiberglass form lifted from the 1955 Ermini. It was so versatile it could be used on a VW chassis or a Corvette chassis, and still look good. A Ferrari it was not, but your neighbors didn’t need to know that.

In the mid 1950s, Dick Jones, an engineer from Compton, California, created a fiberglass body for any chassis with a 100 inch wheelbase, and as Road & Track noted, his finished product “looked more like a Ferrari than anything else.” Like many other such efforts, it was powered by the Ford flathead and had rudimentary suspension. Onlookers, however, didn’t see what was underneath.

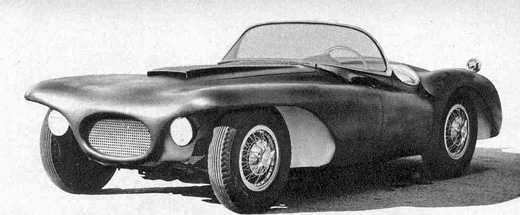

The Bangert was commercially available in 1955.

The Bangert was a more commercially viable effort, well built in heavy fiberglass and could be adapted to anything from a 94 inch MG chassis to a big American frame with a 104 inch wheelbase. This one featured a Corvette windshield, Chrysler Imperial taillights, and clip on wire wheels. It was also offered with a simple frame, using a suspension borrowed from a pre- war Ford–again, handling was secondary.

There were many truly professional efforts as well–one being the Bosley Mk I, which might have truly given Ferrari or Maserati a run for the money, and was used to trailer a Bandini which was rebodied with the ubiquitous fiberglass Devin, as seen below.

Clair Reuter’s Bandini/Devin trailered by the Bosley Mk I in 1959. The Bosley was on of the most beautiful American specials of the 1950s, built by Richard Bosley.

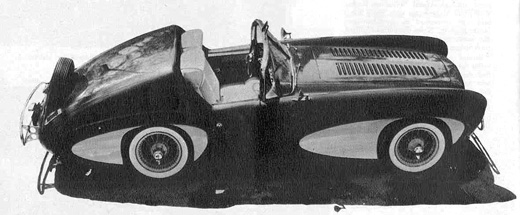

Another relatively professional effort was our lead subject, the 1955 Flajole Forerunner Hardtop Convertible. William Flajole (pronounced Flay-joel) was a styling consultant to American Motors, who, like many other Americans, loved sports cars. And like other enthusiasts, he chose to work with fiberglass, even though there was never any intention of mass producing the car.

Incorporating a massive headrest, the Flajole featured a Plexiglass sliding roof operating on nylon rollers. Rear visibility was very limited, but it was equipped with twin fender mirrors. The scalloped sides would be made famous by the 1956 Corvette, but the styling gimmick was used by Aston Martin as early as 1953, and by OSCA in 1954.

As it was built by a professional, the Flajole also made use of a better chassis than most of the backyard bombs. A Jag XK 120 chassis and engine was used to power the the experimental car.

The Flajole Forerunner in 1955.

Unlike most of the backyard bombs, the Flajole is a survivor. Most of the these homebuilt Ferraris were not much fun to drive, not weatherproof and aged quickly, meaning odds are they were junked early. The Flajole must have been fairly comfortable and easy to drive, for Bill Flajole used his creation until the mid 1970s, saving it for posterity. It was recently for sale at Hyman’s for the paltry sum of $350,000.

The day of backyard bombs is long gone, we fear. The Americans who once abounded with mechanical ingenuity and a remarkable ‘can do’ attitude are waning fast. But once upon a time, if you couldn’t afford a Ferrari in America, you could build one.

Funny you did not mention Kellison. Some are still around and on the street.

There was also the FiberFab Jamaican. One was for sale at the Palo Alto Concours this past June.

One of the Dick Jones cars, painted white with Cunningham blue stripes, survives in Clive Cussler’s Colorado collection. The Bosley was restored by Ron Kellogg, and is now in the Petersen Museum.

Nice overview of the whole trend. Earlier than these there there were things like the Glasspar, the most numerous of the early ’50s efforts, I think Bill Tritt told me he built 300 or more. That might make it the highest production fiberglass body until the Corvette came along. And earlier than the Devin/Ermini Allied built Cisitalia replicas both in the original size and scaled up for American components, one is for sale on eBay right now, in the historically correct, never finished, state.

It’s a whole lot of work to build your own Ferrari, ask Bosley, or Ferrari.