Who is Louis Bionier? Gijsbert-Paul Berk explains the great French engineer

It is well known that Panhard et Levassor, founded in 1886, was one of the French pioneers as manufacturers of automobiles. Panhard et Levassor constructed their first ‘motorcar’ in 1891. Many are familiar with the names of the great designers that shaped the coachwork of French automobiles in the years before and just after WWII. Still, it would not be surprising if only a few can place Louis Bionier and his work.

In the pre-war era, engineers and designers who were employed by car manufacturers or coach building companies generally worked anonymously. The press rarely interviewed the people behind the drawing boards, and by temperament, Louis Bionier was not a man who sought the limelight. However, Bionier deserves to be better known, as from 1929 up to 1967 he was responsible for the chassis and all of the factory built coachwork of Panhard et Levassor.

Apprentice at Appareils d’Aviation Les Frères Voisin?

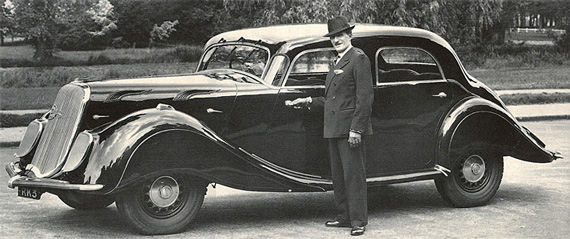

Louis Bionier was a perfectionist also in the way he dressed. In this photo he looks like a bookkeeper, but in fact he was a talented and innovative coachwork designer, who put his mark on many cars made by the French Panhard et Levassor factory.

It has been said that for a short while he was an apprentice in the workshop of the ‘Appareils d’Aviation Les Frères Voisin’, the aircraft construction company established in 1906 by Gabriel Voisin and his brother Charles. However, in 1915 Panhard et Levassor engaged Bionier as ‘ajusteur-outilleur’ (fitter) and he started his career in the factory at the Avenue d’Ivry. By that time Panhard et Levassor was already an important manufacturer not only of large and luxurious passenger cars (they supplied the official automobiles for President Raymond Poincaré) but also of trucks, buses and military vehicles.

In 1918, Paul Panhard a nephew of the founder René Panhard was appointed as General Manager. He was a man with a great sense of social justice and responsibility. He recognized Louis Bionier’s talents and pushed him to develop them.

In charge of the coachwork department

Panhard had its own ‘École Pratique’, an in-house training center for its personnel. Bionier attended their evening classes with excellent results. In 1929, after having gained experience in several departments at the factory, he was put in charge of the department responsible for the design and development of chassis and bodywork. He was just 31 years old by then. Louis Delagarde, his colleague in charge of the design and development of the Panhard engines and military material, was the same age.

In order to manufacture their own coachwork, in 1924 Panhard et Levassor had taken over the factory of the small car maker Delaugère & Clayette in Orléans. Panhard et Levassor was at that time (like Minerva and Voisin) committed to the powerful and silent Knight sleeve valve engines. Their cars had an excellent reputation for quality, but the shape of their bodies was no longer fashionable by the mid 1920s. For this reason many clients engaged the service of one of established French coachbuilding firms such as Binder, Dubos, Fernandez et Darrin, Janssen of Paris, Kellner, Letourneur et Marchand, Vanvooren and Weymann.

The 1934 Panoramic; a breakthrough for Panhard and Bionier

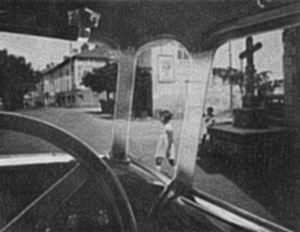

The 1934 ‘Panoramic’ coachwork was a breakthrough for Panhard and for Bionier. The model was called ‘Panoramic’ because of the panoramic view on the road; thanks to the small curved glass panel between thin twin A pillars at both sides of the windshield.

Paul Panhard wanted to change the growing perception that Panhard was no longer fashionable. Bionier was commissioned to design a more modern coachwork style for the Panhard models introduced in 1932. His second innovation was presented at the Paris Motor show of 1934.

The split A pillar of the ‘Panoramic’ was a very practical safety feature. Most humans use both their eyes to look at objects. Due to our ‘binocular vision’ the thin twin A pillars become virtually invisible. This allows us to see the children, whereas one single (thicker) pillar could have hidden them from view.

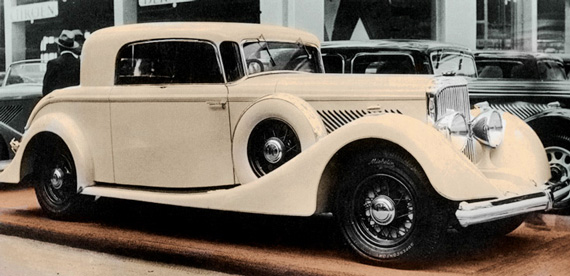

The two-door ‘Panoramic’ Faux -Cabriolet or Coupé was introduced together with the four-door Berline (Saloon) at the 1934 French Salon de l’Automobile in the Grand Palais in Paris. It was one of the most admired cars of the show.

Panhard Dynamic

The Wall Street crash of 1929 also began to affect the economies in Europe. Consequently sales of expensive cars suffered. Paul Panhard, being an ambitious optimist, prodded his commercial and technical staff to beat the competition and gave Bionier a free hand to design a completely new car. There was only one condition: that he retained the six cylinder Sans Soupapes (sleeve valve) 3.5 liter (20HP) and 2.5 liter (14 HP) engines and their rear-drive.

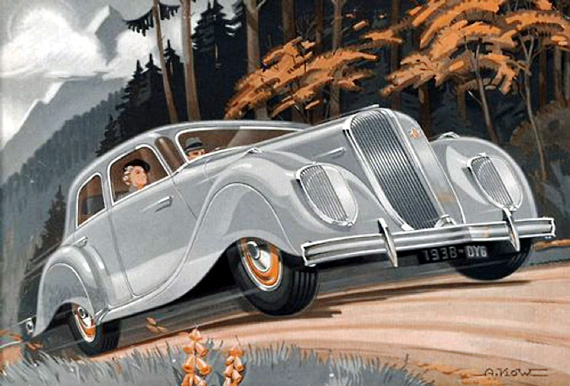

Introduction of Bionier designed ‘Dynamic’ models on the Panhard stand at the 1935 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris. In those days these large front mudguards, which covered and nearly hid the front-wheels, were very much in fashion with French coachwork designers. Several special bodies by Figoni-Falashi and Saoutchik had them as well. Between 1936 up to 1940 around 2.300 Dynamics were produced.

The result was the Panhard Dynamic, introduced in May 1936. In many respects it was an outstanding car. It was a roomy six-seater, with the driver positioned in the middle of the front seat behind a central steering wheel. The windscreen was fitted between two small curved windows similar to those in the ‘Panoramic’.

Louis Bionier standing next to a 2,5 liter Panhard ‘Dynamic’ four-door Berline (Saloon). Even if the shape of this roomy six-seater was not the paragon of elegance, this Bionier design was a very practical car with a relatively low aerodynamical (drag) coefficient. Like its predecessor it had split twin A pillars to give a panoramic view.

Bionier abandoned the conventional ladder frame. Instead, the Dynamic had a monocoque (body-cum-chassis) construction with a rear suspension using two longitudinal torsion bars. It also had hydraulic brakes on all four wheels, but with two separate hydraulic circuits each with a separate master cylinder. Thanks to its smooth and silent power, good road holding and impressive comfort, it was a very nice car to drive. However, sales were disappointing. Until the end of October 1934 only 840 had found a buyer, whereas the Panhard management had planned to produce some 4800 units per year.

Why a dynamic design became a commercial catastrophe

What were the reasons for this commercial failure? Was it the modern styling, with wide front mudguards, which practically hid the front wheels (to reduce drag) and ‘waterfall’ grilles over the radiator and the headlights? The sales of the new ‘streamline’ styled Peugeot 402, and the low front-wheel-drive Citroën, introduced at about the same time, proved that the French motoring public was not averse to modern design, but it is certainly possible that for the conservative hardcore of Panhard customers the Dynamic was a bit too far ahead of its time. The monocoque construction also prevented prospective clients having their car bodied by one of the coachbuilders.

The first Panhard Dynamics had the steering wheel at the center of the windscreen. As many customers found it impractical to slide over to the middle of the front bench, on later models the steering wheel was mounted on the right-hand side of the car. In the mid thirties this was not uncommon on French luxury cars. But as traffic in France normally kept to the right-hand side of the road, an increasing number of French makers of popular cars were by then designing the steering at the left-hand side.

A real and serious problem was that the new Dynamic models were rather expensive. Their price tag went from 58.800 up to 70.000 Francs, whereas the new 2-liter, 6 seat Peugeot 402 could be bought for 22.900 Francs and a wide bodied 5/6 seat Citroen 11 B cost 21.500 Francs. One of the reasons for this was that sleeve valve engines are more complicated, demand more precision machining and are therefore more costly to produce than engines with poppet valves. Also, comparing performance and fuel consumption, sleeve valve machines were not competitive anymore. The political situation in France, reflecting great social unrest, was possibly another factor.

Apart from the four-door Berline, Bionier designed two Dynamic Coupé models with respectively two and three side windows. There was no possibility to order the Dynamic with a custom body because the car had a monocoque construction and Panhard provided no special platform chassis for specialists coachbuilders. However, there have been number of Dynamics converted to cabriolets.

Panhard’s financial situation was saved by a contract from the French army

After a parliamentary victory of the Front Populaire (a powerful coalition of left-wing parties against Fascism), the industry was forced to pay higher wages and improve labor conditions. Higher wages, reducing the number of working hours and providing fully paid holidays strongly increased the labor costs and for the first time in its history the balance sheets of the company Panhard et Levassor showed a deficit. It was forced to reduce its workforce and from the first to the sixteenth of June 1936 the factory was occupied by protesting workers. Fortunately after long negotiations between Paul Panhard and high placed French government officials, the future of Panhard & Levassor was temporarily saved by an order of 400 military trucks and light combat vehicles.

A later type Panhard Dynamic Berline, with its steering wheel at the right side of the body. Note the three windscreen wipers. Bionier was from his early beginning as a designer concerned about the safety of the Panhard clients. This particular car has participated at several recent Concours d’Elégance in the USA, notably Amelia Island and Pebble Beach.

In the meantime Bionier adapted the Dynamic to be more in tune with the wishes of the clients. The steering wheel was moved to a more conventional position at the left of the car. The range was furthermore extended with a two-door coupé with a trunk, a two-door convertible and a six-window sedan that could seat nine. The latter was also sold to the French army as a staff car for senior officers.

When in 1940 the German Army approached Paris, Paul Panhard moved most of its production and technical personnel from their factory at the Avenue d’Ivry to their subsidiary at Tarbes in the south of France (Midi Pyrenées). After the military defeat of France on 25 June 1940, the French authorities ordered them to return to Paris. During the years of the Nazi occupation the Panhard works were requisitioned and forced to work for the German Army. Part 2: 1940-1950

Thanks Pete, another great story.

Are there any current automotive stylists/designers reading Veloce Today?

If so, please take some inspiration from the ‘Panoramique’. At least in the US market, there are very few cars that give the driver a reasonable view. I don’t want a camera or any other gimmick, I want a car (not suv/truck) with reasonable sized windows and small-ish pillars so I can see out, in all directions.

I too would like to see such stylish cars produced again, and Doug’s comments about the clear all round visibility show we have not improved in every area over the last century.

Alas, I suspect with car manufacturers having to meet so many legislated requirements and relying on more computers to generate simulations for aero efficiency and stress analysis they will inevitably all arrive at the same solutions. To meet fuel consumption targets there are aerodynamic considerations, hence the long steeply raked windshields now prevalent, and then roll-over crash tests dictate the strength of the thick side pillars. If visibility is thus restricted, well hey, modern technology says you can have cameras to cover every angle – but then we would have to be driving looking at a small screen rather than the road ahead. And that is progress?

At least the modern car is not allowed a ‘Spirit of Ecstaasy’ type mascot on the front, so now when you hit those two kids in the blind spot (that in the Panhard you would have been able to see anyway) they will escape with minor bruises.

Not much chance a 1936 Panhard would pass any modern type approval. I know they would say it is for our own well-being, but how did the civilised world let it get itself so tightly controlled by rules and regulations?

Very informative article with some confusing entries. The actual car names were Panoramic and Dynamic respectively and the Dynamic was never made as a right hand drive…started as a central steering wheel that migrated to the left and the transmission shift lever went from a dash mount to a floor mount and loss of one wiper with the steering wheel position transition (1938). Ref. Panhard, la doyenne d’avant garde, Benoit Perot, 1979.

French language is always fun, even when in English! Mistake is mine; I should have checked the model spelling. Thank you for reading this wonderful work by Gijsbert-Paul Berk, and we hope you will enjoy the next few chapters. The Editor.

Thank you for the informations about Panhard & Levassor, particulary about Louis Bionier.

As webmaster of our new website I’ll mention the link of your website for our english speaking members ( 75 in the world , 3 in USA )

Our new version will be online in september, in the meanwhile the fans of the oldest mark can visit our ( old ) website .

http://doyennes.pl.free.fr/index2.html

I’m the owner of a X 72 panoramic, 1934 in restauration, and hope to be ready in 2016…

Sinceraly

Gilles