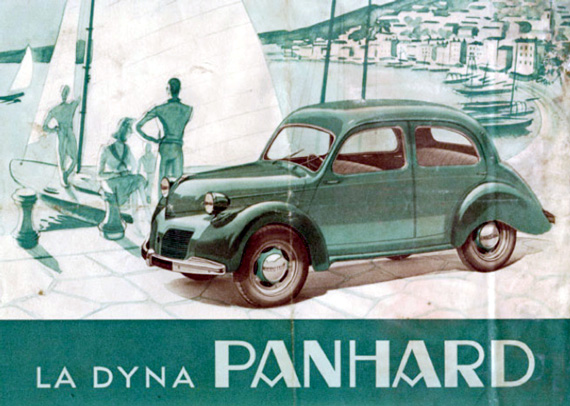

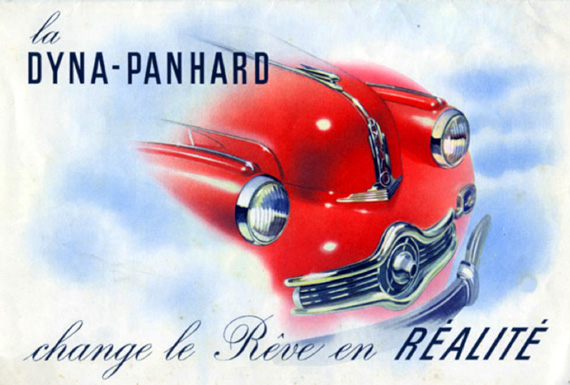

‘Like in an airplane.. the Dyna will make you free from the harshness of the ground and its resonances’ is a free translation of the text in this Panhard publicity folder.

By Gijsbert-Paul Berk

In Part 1 of his look at Panhard’s remarkable Louis Bionier, Gijsbert-Paul Berk described how Bionier designed the Panoramic and Dynamic Panhards in the 1930s. In Part 2, we learn how the post-war Dyna X was developed.

Was the Panhard Dyna an automotive cuckoo’s egg?

There are some mysteries concerning the origin of the postwar Panhard Dyna.Was it designed by Jean-Albert Grégoire (as some French experts claim on Wikipedia) or by the duo Louis Delagarde, Louis Bionier at Panhard & Levassor? The story of the gestation of this interesting car was extensively described in the review by Peter Vack of the book ‘Panhard, the flat twin cars 1945-1967’ by David Beare on VeloceToday of 8 August 2013 but if you want to refresh your memory we must take you back to the prewar years.

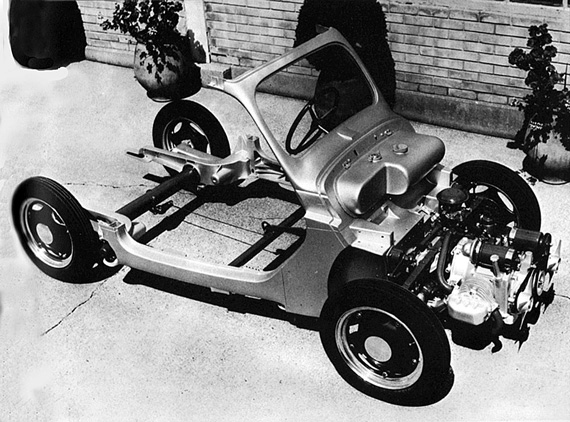

The chassis of the small AFG car which Jean-Albert Grégoire developed during the War, consisted of molded aluminum parts. Its construction was based on his experience with designing the pre-war Amilcar Compound.

Grégoire was a brilliant and highly qualified engineer. He was co-inventor of the constant velocity (homocinétie) joint for front-wheel drive cars and started building and racing his small Tracta sports cars to prove their worth. He made more money from the licensing rights of the Tracta joints he sold to various companies, but the successes of his Tracta cars established his reputation as a front-wheel drive specialist. In 1936 Hotchkiss, which had acquired the French sports car maker Amilcar, approached Grégoire and commissioned him to design a front-wheel drive car. Together with the Compagnie Aluminium Française (later to become Péchiney) Grégoire developed a new technique to achieve a very light and strong car. Its monocoque type chassis consisted of large Alpax (a high grade aluminum) castings, bolted together with steel pressings. The Amilcar Compound was shown for the first time at the 1937 Paris Motor show. It was available with three different body styles: a four-seater coupé, a four-seater cabriolet and a closed van. From 1938 till the outbreak of WWII some 900 of these Amilcars were produced.

In 1942 the first prototype of the AFG car was ready for road testing. The car had an air-cooled flat twin engine of 600 cc that drove the front-wheels and gave a top speed of 90 km/h.

One of Grégoire’s wartime adventures; designing a new small car.

After being released from the French army in September 1940, Grégoire returned to his small workshop in Paris. Although the occupying forces had strictly forbidden the French car manufacturers to design new passenger cars, Grégoire continued to experiment and design cars. One of his projects was an electric automobile that was produced as the CGE Tudor. The second was a very small two-door car seating four people, its front wheels driven by a small 600 cc air-cooled flat twin engine. Grégoire knew that he had to limit the weight of the car to a minimum to get a reasonable performance. Because of his experience with the cast Alpax chassis elements for the Amilcar Compound he contacted the management of the Compagnie Aluminium Française and they agreed to sponsor building a few prototypes.

In June 1942 the first AFG (Aluminium Française Grégoire) car was ready for testing. The small semi-convertible with its canvas top weighed only 400 kg, had a top speed of 90 km/h,. and consumed only 4 liter/100 km (58.75 Mpg/US).

Peddling the design of the AFG prototypes

Immediately after the liberation Grégoire set out to show his prototypes and offer the production rights to the major French car manufacturers but met with with limited success; during the war Renault had developed their own small car, the Quatre, Citroen was redesigning their Deux Chevaux (originally planned to be launched in 1939) and Peugeot was not interested in a small car. Simca, after a lot of haggling and manipulations (they even offered Grégoire a directorship and produced two Simca / AFG prototypes), finally chose to continue building the Simca Cinq (based on the Italian Fiat Topolino).

Panhard et Levassor bought the manufacturing rights for the AFG car from the Compagnie Aluminium Française, which had financed the project. Their contract included the provision that Panhard should pay Grégoire a reasonable compensation. It also gave Panhard the right to alter construction details if mass production required different solutions.

Why did Panhard buy a design that Renault, Citroen and Simca rejected?

From the well-researched book about the history of Panhard et Levasseur by Claude-Alain Sarre (published in 2000 by E.T.A.I., Paris) one can distill the following reasons:

1. Practical considerations. It was clear to the Panhard management that in postwar France there would be no market for the kind of passenger cars they had produced up until 1940. Already in 1941 and 1942 a small group of Panhard engineers (Louis Delagarde and Louis Bionier with a few confidants), led by Jean Panhard (eldest son of Paul), had started on the design of a small front-wheel drive car powered by a 350 cc flat twin engine. A prototype of the engine existed but not of a complete car.

2. Political considerations. Cooperation with the Compagnie Aluminium Française and acquiring the rights to use the AFG design gave them the support of Paul-Marie Pons, the deputy director of the French Ministère de la Production Industrielle. Pons was the man behind the master plan for the postwar French automobile industry that bore his name. He had made it clear that he very much wanted to see the small AFG car being produced. Originally he had refused to provide Panhard et Levassor with steel or allow them to resume manufacturing passenger cars. However, as a result of their switch to a concept that used a lot of aluminum, the company was included in the Pons Plan.

The input of Louis Bionier and Louis Delagarde

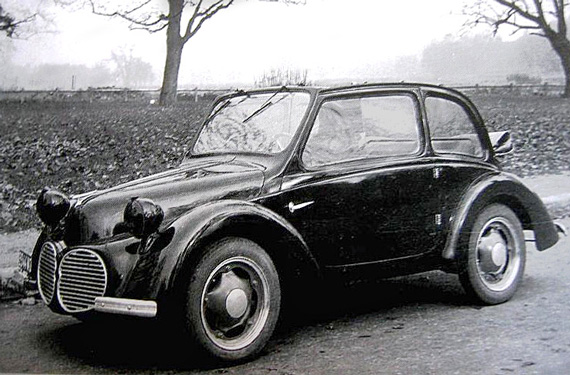

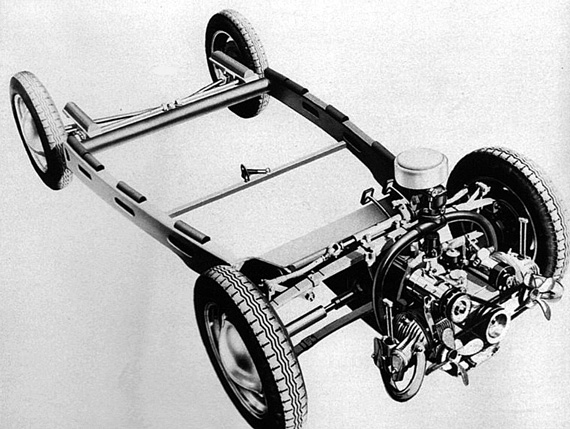

Just as Grégoire’s AFG concept, the Panhard Dyna had an air-cooled horizontal two cylinder engine driving the front wheels. But apart from this, the chassis of the Dyna was completely different from the AFG design. The first series Dyna had twin fans for engine cooling.

It was up the team of Louis Delagarde and Louis Bionier to merge Panhard’s own concept with that of Grégoire. For political reasons (to not upset Monsieur Pons), they were instructed to conserve as much of the AFG design as possible. However, Delagarde had himself designed an air-cooled 350 cc flat twin as part of a project for an opposed 12-cylinder engine for future use in military vehicles. He enlarged the capacity to 610 cc and with a compression ratio of 6.25 it then produced 22 bhp @ 4000 rpm, against the 15 bhp of the 600 cc AFG machine. This engine was also mounted in front of the front axle to drive the front wheels. Delagarde chose a different power train layout than Grégoire. The AFG concept had the gearbox behind the differential housing and the shafts that drove the front wheels (similar to Lefebvre’s front drive Citroën Traction Avant). In the Panhard design the differential housing was placed at the rear of the gearbox. Delagarde’s chosen lay-out of engine, clutch, gearbox and then differential conformed to the engineering tradition of Panhard.

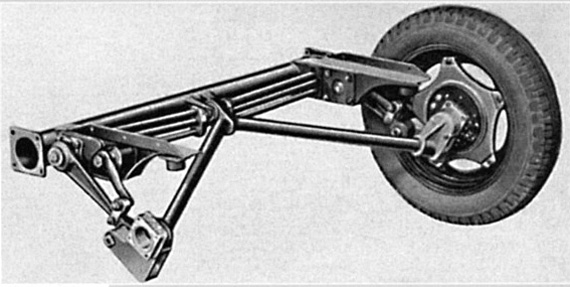

Close-up of the Panhard Dyna semi-independent rear axle with torsion bars as suspension units. To adjust for the weight difference between a fully laden car and one with only the driver on board the rear springs of the Dyna were rather stiff. This, combined with the relatively high load at the front, meant that when cornering fast the Dyna sometimes lifted its outside rear wheel. Like a dog who is going to…

The Panhard et Levassor management considered the AFG body a bit too small for a family car and so insisted that it should be larger and have four doors. This, plus the cost and other disadvantages (such as the transmission of engine vibrations) of AFG’s integrated cast Alpax chassis, meant that Bionier had to redesign chassis and body. The new chassis had side members of Alpax but a pressed steel floorpan. The wheelbase was increased by 7 % and measured 2.13 m (84 in). For reasons of space and budget a beam axle and torsion bar springs replaced the AFG independent rear suspension. Although the new four-door body was still made from high grade aluminum, to create more interior space it was at 3.82 m (150 in) 10% longer, at 1.44 m (57 in) 11% wider and at 1.53 m (60in) 6% higher. A consequence was of course that it was also heavier. The Panhard Dyna X berline (sedan) had a dry weight of 550 kg (1.200 lb), 38% more than the two-door AFG with its canvas roof.

The front of the first series Panhard Dyna seemed inspired by that of Grégoire’s AFG car. But this was not Bionier’s first choice. There was a political reason. Panhard et Levassor had bought the rights to produce a car similar to the AFG concept, in order to get the permission of the mighty Monsieur Pons, to allow them to produce passenger cars.

Bionier gave the body a slightly rounded roofline that emphasized a certain family resemblance with the style of the prewar Panhard Dynamique but above all improved its aerodynamics. This had a positive effect on the maximum and cruising speeds; the new Panhard could do 100 km/h, a gain of 10% over the AFG prototype. Thus, the final result, the Dyna X, owed quite a lot to the input of the Panhard engineers. It was in reality more a Panhard design than an AGF clone.

Grégoire’s bitter comments

Grégoire seems to have been quite unhappy with the changes to his original design. In his autobiography 50 ans d’automobile , (published in 1974 by Flammarion, Paris) he is extremely critical about the engine and transmission designed by Delagarde. Grégoire violently attacks Delagarde’s decision to use roller bearings as main bearings for the crankshaft and the use of torsion bars as valve springs. He considers the engine and gearbox that Delagarde designed unnecessarily complicated and expensive to produce. He even goes so far as to state that he has calculated that Panhard could have saved at least 120 million Francs (Francs of 1967*), if they had retained his power train and adds that this money could have been used to invest in the development and production of a four-cylinder engine and would have prevented the takeover of Panhard by Citroën.

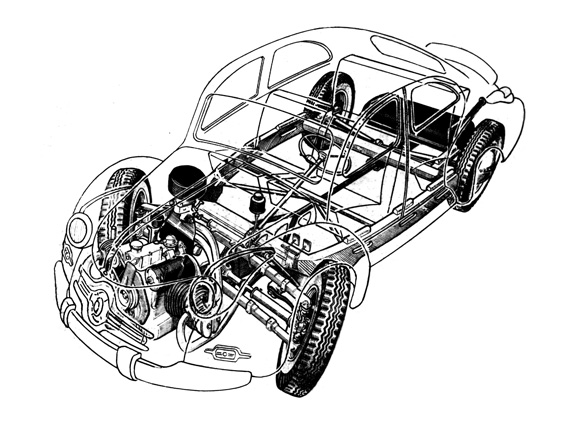

Phantom view of the Panhard Dyna X 86. This kind of cut-away drawing was popular to unveil the technical layout of new cars. Leading European car magazines employed their own artists to make these illustrations and most European car manufacturers provided such documents in the Press kits for the introduction of their latest models.

Grégoire did not like the Bionier designed coachwork either. Although in his book he admits that the body of the Dyna X shows some similarity to his AFG design: “when you see a Dyna on the road, it resembles a sister of the AFG… but a sister who suffers from cellulite”.

Were Grégoire’s acid accusations caused by jealousy, his wounded pride as an engineer or because he was still angry with the Panhard management, who at first had refused to pay him his royalties? Only after a bitter juridical fight it was eventually agreed that Panhard et Levassor would pay him 0.3% of the sales price over the first 2000 cars sold. Note: Total production of the Dyna X between 1947 and 1954 was 47,049.

Praised by the press

An early publicity folder for ‘La Panhard Dyna’ in a holiday setting of a bay with a few boats. A contrast with today’s overcrowded ‘Marinas’ on the French coasts.

During its first presentation at the 1946 Paris Motor Show the new Panhard Dyna X84 drew great crowds and received a lot of positive comments from press and visitors. The road tests of the first production models were full of praise as well, and not only those in the French motoring press. In their issue of 23 April 1947, the British car magazine The Motor published a first impression under the title “Dynamic Demonstration, Remarkable Pulling Power and Road Holding, combined with Full Accommodation for Four Passengers”. They went on to write, “What we had not anticipated was a car with such ‘grown up’ manners, such quietness and such remarkable road holding characteristics…”

However, it must be noted that the new Panhard was relatively expensive. The 3 CV Dyna X84 cost about 40% more than the 760 cc four-cylinder rear-engined Renault 4 CV which was also presented in 1946. The Renault provided slightly less interior space but comparable performances and it had a four-door body as well but price was not (yet) a big issue in those first postwar years; there was such a shortage of automobiles in France that buyers were prepared to pay anything to get a new car.

• Note: In 1960, the new franc (“nouveau franc”) was introduced worth 100 of the old francs. So if Grégoire was quoting 1967 values he was referring to the new franc, the equivalent sum for the period of the Dyna’s development would therefore have been 12,000 million.

The X-86

It seems that Bionier himself was not satisfied with the styling of the Dyna X84. He felt that his bosses had forced him to a compromise because they had insisted that the car must look as much as possible like the AFG prototype.

That Panhard intended the Dyna for an up market clientele is made crystal clear by this photo from the factory press kit. In 1947 Christian Dior, the French Couture King, introduced the so-called ‘New look’. One of its features was a skirt falling to below mid-calf, such as the one worn by the lady on this photo. These long ‘New look’ robes were certainly very elegant but required nearly double the length of textile, than was customary in the early postwar period, with its shortages of all kinds of goods and materials. Therefore, new look outfits were quite expensive. The average young French middle class woman could only dream having one.

Indeed the front with its old-fashioned style mudguards and protruding headlamps bore a strong likeness to the Grégoire car whereas the passenger section, roofline and rear were reminiscent of Bionier’s own pre-war Dynamic design. A face-lift in 1950 added some chrome strips and included a new grille. According to Panhard’s press information, it symbolized the replacement of the twin cooling fans by a single one.

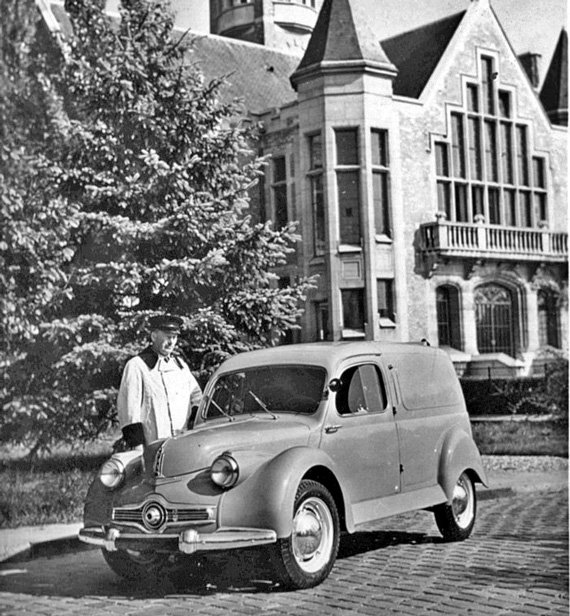

Panhard built not only passenger cars on the Dyna chassis but a delivery van as well. Although rather expensive to purchase, its owners valued it for its frugal petrol consumption. Besides, its small size made it a very practical vehicle for urban use.

This was one of the improvements that increased the power of the flat-twin engine to 28 bhp but it seems not unlikely that the Dyna grille was inspired by recent styling fashions in the USA. Both Ford and Studebaker had just introduced new models with grilles that had strong horizontal accents and a center resembling the propeller of an aircraft.

Deep in his heart Bionier would have preferred to make the nose as smooth as a bullet. What he had in mind was called the Dynavia.

Next: Bionier gets his wish.

VeloceToday Select Number One:

VeloceToday Select Number One:

Cuban Grand Prix, 1957

by David Seielstad

Excellent read. Good insight to the pre war development in the French auto market.

Politics did not escape the engineer and his dream of having a great idea reach fruition. Great idea men are fraught with compromise.

A good story to illustrate the development of this car.