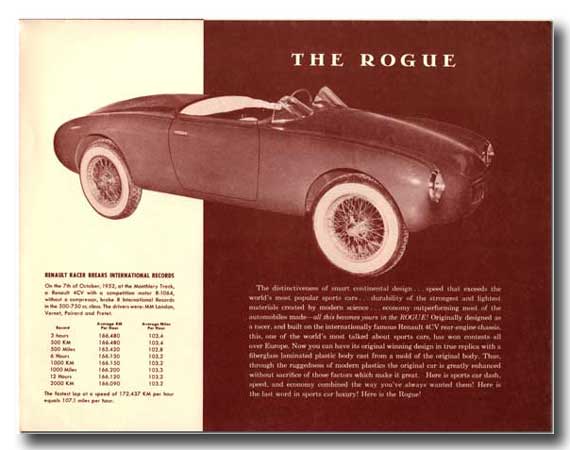

In Part 1, Barn Find, Smith described the search for the elusive “Marquis” which resulted in the amazing barn find of the Rédélé Special Number 2 in Pennsylvania. Part 2 deals with an eager American businessman, Zark W. Reed, who had a plan for Jean Rédélé and his car. Above, the Rogue; was this design by French racing driver Louis Rosier really the “Marquis”? And what is the connection to Rédélé? Read on.

By Roy Smith

Dreams of Glass

1953 witnessed the first Chevrolet Corvette to roll off the assembly line in Flint, Michigan. The concept of an all-glass-fiber production sports car had just become a reality. Glass fiber had arrived on the scene many years before. In the 1880s a glass maker from Massachusetts by the name of Edward Drummond Libbey had first discovered that glass in fiber “staple” silk-like format could be woven as a fabric – he even had a dress made that was exhibited at the Chicago World Fair in 1893.

Taking a leap to 1938, we see a gentleman by the name of Russell Slayter eventually create the product generically to be known as glass fiber and the trade mark “Fiberglas” (with only one ‘s’) was born. Our Mr. Slayter had produced a continuous as opposed to a staple textile filament. The continuous filament was easily woven into a fabric which when treated with a new type of chemical resin would set up very hard. The world at that time was on the brink of war and although this was a global disaster for populations, for science it was to drive forward many emerging creative technologies. Amongst these polyester resins and the use of molded glass fiber, which was found to have great strength when used in layered laminated format.

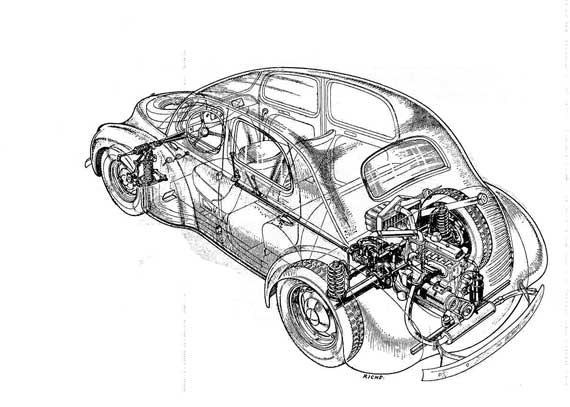

With the end of World War II, in France the pre-war-designed Renault 4CV finally saw the light of day. It would become a massive success story for Renault and from early on spawned the design of several lightweight sports cars using the simple 4CV chassis as a starting point. Men like Vernet and Pairard, Labourdette, Chappe and Gessalin would all take a look at the use of laminated “polyesters”. Included among these was of course the clever, opportunistic mind of the man Jean Rédélé.

Cutaway of the 4CV shows a platform chassis that could be easily adapted to fit a new fiberglass body.

Plasticar’s aims were ambitious, as they estimated that they could fit a bodywork assembly made of just seven elements and attached directly by washers and bolts to the floor pan of the Renault 4CV in fifteen minutes and produce 3000 cars a year. They wanted to compete with the U.S. imports of the-then popular English roadsters familiar to soldiers who had been based in Europe and were returning home smitten by the Triumph TR2, MG and Singer.

Zark W. Reed was a tactician, though also perhaps a bit of a dreamer (Pierre Lefaucheux called him “woolly-minded”). But nothing would stop him. Reed obtained an agreement in principle with Renault concerning the Renault Rosier, using that design to create a car with a glass fiber body; they would call it the Rogue. But Zark was not content with this: he wanted to go further and up the ante by directly approaching another partner –Jean Rédélé.

Original aluminum-bodied Rosier Renault, 1953 Note similarity to the Rogue in the brochure above. Number 53 was a combined effort of Louis Rosier, son Jean-Louis and Renault, using an upgraded 747 cc Renault engine. It finished fourth in class in the 1953 Le Mans race. It was officially listed in the results as a ‘Renault 4CV 1068 Spyder’. (©Renault Communications)

Rédélé jumped at the chance of finding himself potentially in the saddle for a production deal and a shot at the lucrative American market. Shortly after his meeting with Renault, Reed visited Rédélé, who had an office in the rue Forest in Paris operating from Escoffier’s Grands Garages, Clichy. Rédélé took the American out on the road in his race-winning Special (number 1) and Zark Reed was immediately won over by the car and its owner. Reed decided he wanted the rights to produce the car industrially in the USA, but with a glass fiber body. Rédélé saw the possibilities: was his dream about to become reality? Here was a company which was experienced in glass fiber and it looked like a superb opportunity to become a constructor. Rédélé didn’t have the financial wherewithal himself to produce his own cars at that point, so he decided to sell Reed a manufacturing license for the sum of $2500. But Reed stipulated in the contract that the licenser must supply him with a master to work from; that master mold would come from the second “Renault Special”.

New York Auto Show, 1954. The Rédélé Special number 2, then owned by Plasticar, is exhibited at the show as an example of what the new Marquis might look like.

For Rédélé this was perfect, and the car was sent by ship to the New York Motor Show early in 1954. Reed had moved fast; he had PlastiCar brochures made up and published photos of the car in preparation for production, being hopeful of receiving many orders at the show. Happily, it received flattering comments from those who saw it. Zark Reed was delighted.

But the fiberglass dream was about to turn to a nightmare for PlastiCar Inc, Rédélé and Renault.

Next: Shattered Hopes