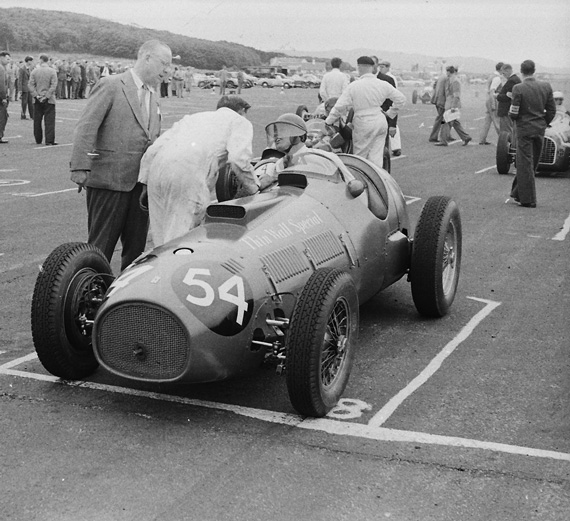

The first Ferrari Mike Hawthorn raced was this modified 375 4.5 litre car, the Thinwall Special entered by Tony Vandervell seen standing beside the car. The meeting was at the Turnberry circuit in 1953.

Story by Denise McCluggage

Photos and captions by Graham Gauld

There have been many “firsts” in the life of John Michael Hawthorn starting that tenth day in April, 1929, when he first saw light of day. His father, Leslie, was a garage owner and a man active in motorcycling and motor-racing circles, putting Mike close to this world from the time he was a tyke.

His first time at the wheel of a car was when he was eight. He “borrowed” an old Jowett that had been left for repair and, with it in gear and the engine off, ground it around a field behind the garage on the starter motor. His first vehicle was a 1927 Norton motor-bike which he owned when he was 14, but for tinkering purposes only as he was too young to drive on the road.

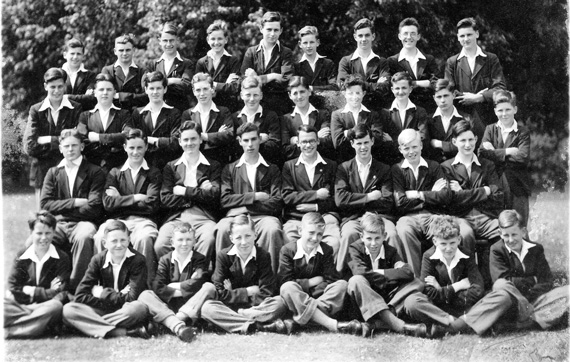

A youthful Mike Hawthorn at Ardingly college in Sussex. He is easily recognized by his blond hair, second row from the bottom, second in from the left.

His first season in a single-seater was 1952 when a friend of his father’s bought a two-liter Cooper-Bristol for him to run.

His first Grand Prix was the same year, it was the Grand Prix of Belgium at Spa and he was fourth in the Cooper-Bristol. His first crash was at Modena in his Cooper when he went there to drive a Ferrari, his first trial for that Scuderia. He was not seriously injured and neither was the impression he had made on the Ferrari folks because at the end of 1952 he became the first English driver since Dick Seaman to sign with a continental racing team.

When Ferrari signed him, Mike was just 23-years-old. He was a mere two years beyond his first “go” at Brighton. And he was six years before his championship at Morocco. There was to be a fabulous first season just one step ahead. And then there was a long row to hoe through four up-and-down years that saw several crashes and severe burns; a kidney operation; the death of his father, to whom he was extremely close, in a road accident; the death of a very close friend in another accident; the grim tragedy at Le Mans in which he was the first link in a chain of disaster; and the frustrations of driving G.P. cars.(Vanwall and B.R.M.) which were still in the early stages of development and — although capable of leading — seldom capable of finishing.

One of the early sports cars he raced, Len Potter's Frazer-Nash Mille Miglia at Charterhall in Scotland.

Mike’s first year with Ferrari, 1953, was probably one of the most successful rookie years ever. In his first three races for the prancing horse he finished fourth, third and second. Then came the Grand Prix of France which was the high point of the season and perhaps of Mike’s entire career. Certainly it was one of the most exciting Grand Prix ever and in Rheims they still suck in their breath when it is mentioned. At the mid-way mark of the race, there were seven cars running under a blanket.

And look at the fast company this young Englishman was keeping: The order ran Fangio, Hawthorn, Ascari, Farina, Villoresi, Bonnetto, Gonzales. Gonzales had been leading until he stopped for fuel. Then the lead proceeded to be passed back and forth like a Black Jack deal between Hawthorn and Fangio. A report at the time said the lead changed twelve times.

There wasn’t a single grandstand seat being sat in and the pits were an un-businesslike frenzy of excitement. “We would go screaming down the straight, side by side absolutely flat out, grinning at each other, with me crouching down in the cockpit, trying to save every ounce of wind resistance”, is the way Hawthorn describes it in his book, Challenge Me the Race. “We were only inches apart. I could clearly see the rev counter in Fangio’s cockpit”.

Dicing with Fangio is one thing. Crossing the finish line ahead of him quite another. Mike knew that if he left the hairpin turn onto the pit straight just ahead of Fangio, Fangio would slipstream him and then nip past just under the flag. He knew, too, that Fangio was too wary an operator to let a “new boy” slipstream him. Hawthorn found the extra impetus he needed out of the final turn by slipping down into first gear and literally blasting his way out of the turn. He beat Fangio across the line by a second. And Gonzales finished only a few feet behind Fangio and Ascari some three seconds behind him. The Autocar reported: “It was a battle which exhausted even the spectators with its intensity and duration”.

Hawthorn’s second year with Ferrari was much different. Early in the season he was painfully burned in a crash with (Froilan) Gonzales at Syracuse. Then the news of his father’s accident reached him at Le Mans. And when he returned home to England for the funeral he found himself the center of a brouhaha over whether or not he had been dodging his military service. (He had at one time been deferred as an engineering student.)

Press, public, and even Parliament took up the matter. Mike has never been one to explain himself nor go out of his way to smooth ruffled public relations. He did not then. And the storm raged. As it turned out, he would have been deferred on physical grounds, if not because of his burns then because of his kidney condition. He was to go into the hospital for surgery for that soon, but not before he went to Barcelona and won the Spanish Grand Prix. That, and the Supercortemaggiore, a sports car race, were his only victories for the year.

Again at Charterhall in Scotland, Mike wins the Formula Libre event with his Cooper-Bristol ahead of Denis Poore's Alfa Romeo.

In 1955 Mike and Ferrari parted company, not too amicably because no one parts amicably with Ferrari. The Commendatore is a strong man. The disagreement was over Mike’s wanting to race for a home team, Jaguar, in the limited program they had scheduled and drive Ferrari in the Formula 1 races. Ferrari did not wish to share him. Mike chose Jaguar.

He won Sebring with Phil Walters in Briggs Cunningham’s D-jaguar, but it was not an unclouded victory. The laurel wreaths and the congratulation first went to Phil Hill and Carroll Shelby who shared a Ferrari. Then a re-check of lap charts gave Jaguar the victory.

But the Le Mans victory with Ivor Bueb was even more clouded. That was the year that Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz hit the wall across from the pits and sluiced through the crowd cutting a swath of fire and death. The Mercedes had dodged an Austin Healey which had spun in dodging Hawthorn’s Jaguar as Mike cut sharply in front of it to stop at the pits which lined the all-too-narrow road way.

There was no room for dodging. The Mercedes clipped the Healey and smote the wall and spread its lethal parts through a tightly-packed crowd.

Some eighty people died in that disaster. Hawthorn was quickly cleared of any responsibility for the crash in the investigations that followed, but the press – particularly the German press — did not let the matter drop. Perhaps in the effort to disprove accusations that the Mercedes-Benz magnesium body burned with abnormal intensity and to disprove the wild rumor that the car had carried a secret, highly-volatile fuel, the German papers overemphasized Hawthorn’s part in the chain of events that ended in the tragedy. Since then, anyway, Hawthorn has at best been a controversial figure in Germany and even today some German writers attack him fervently with personal animosity.

Hawthorn’s popularity in Germany was not enhanced by his being black-flagged for passing “dangerously” and bumping a Porsche in the tail during the 1000 Kilometer race at the Nurburgring two years ago. The next chapter of this anti-Hawthorn book came when he was refused an entry in the G.P. of Germany in 1956. The insurance companies refused to cover him, it was said. This caused a great ruckus in the motoring world and many letters-to-editors in many languages.

But since then, as Richard von Frankenberg, the noted German journalist and driver has said: “The waves have calmed”.

The text of this article originally appeared in the January 1959 issue of “Sports Cars Illustrated” and is reprinted here with permission of the author and “Car and Driver” magazine.

I do not agree with some of your thoughts reg. the German “animosity” .

It was the American driver John Fitch who convinced Mercedes to retire their cars just upon the Le Mans tragedy.

Furthermore an old amateur film from France came to light recently that clearly confirm that Mike Hawthorn had been responsible for the accident.

To see the smiling (!) Hawthorn taking the silverware while medical doctors still tried to save the lives of many victims of this fearsome crash was too much for many French people. Then …and still today!

WWII was just 10 years away and Mike Hawthorn had strong resentments against anything German. Thats understandable although Jon Fitch and Stirling Moss thought differently then….!

However, Hawthorn was a great driver who deserves to be still loved by English race enthusiasts. But he was a strange character sometimes and seemed not very stable psychologically.

Hey Walter ! sorry you are so wrong , in so many ways , It was an accident , everyone felt bad , no one persons fault , you could not recreate those situations that lead to that terrible accident again if you tried 10000 times ,…… By the way Great site Guys