Review by Pete Vack

Photos from the book

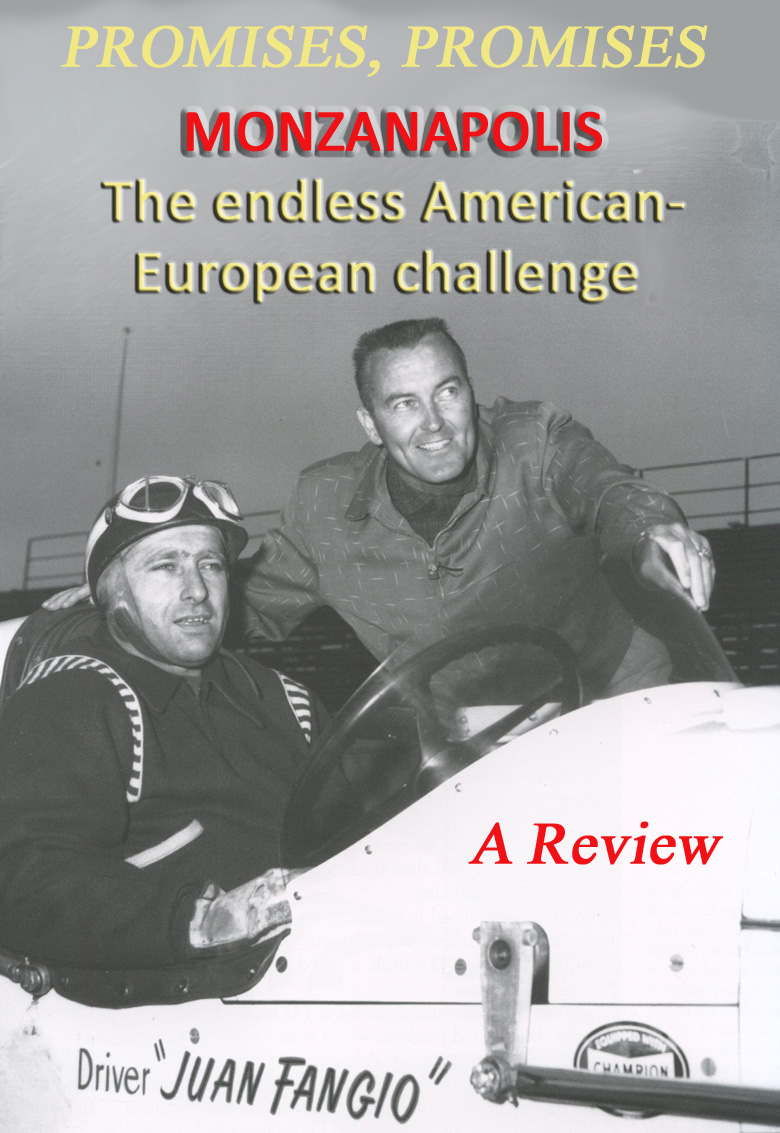

Aldo Zana’s excellent new book is primarily about the 1957-58 Race of Two Worlds, which Zana coins as “Monzanapolis” and is the short title of his book. It fulfills almost all the criteria we look for in a book today; it sheds light on relatively untouched subject matter; it is written from a unique and knowledgeable perspective; it is well-researched using material from multiple sources; it presents clear and rarely published photos; it offers notes and sources at the end of each chapter. There are versions in both English and Italian so the text runs smoothly in both. It is a joy to have and to hold.

Zana writes of the well-known Peugeot/Ballot/Bugatti efforts at Indy, but also of the 1925 Pietro Bordino Fiat 805 which finished 10th.

The book is subtitled “The endless American-European challenge” which include much more than just the race of two worlds. Carefully edited to achieve a tightly focused work, Zana has worked his way through a plethora of possibilities to tell us about not only the Races of Two Worlds, but of the American/European face-offs that began with the Vanderbilt Cup of 1905, continues with Indianapolis in 1913, take us to France for the 1921 French Grand Prix at Le Mans, Italy for the convention-breaking 1923 Grand Prix, covers the 1936-37 Vanderbilt races and back again to Indy before concentrating on the Races of Two Worlds. Zana tells us in the Introduction that he will focus on this American/Europe challenge, selecting “the most significant events from 1905 to 1937….According to such a selection the presence of European cars, mostly Alfa Romeos and Maserati from Italy, driven by American drivers on American soil have been skipped. Similarly, the too long chapter on US Sports Car racing, dominated by European cars, has also been ruled out.”

Jimmy Murphy and the fantastic Duesenberg came, saw and conquered the French at Le Mans, 1921, but was ignored at the awards ceremony. It would take decades before another American car was capable of winning a Grand Prix.

The thesis allows that the teams themselves must be foreign to the event, not just the car or driver (though there are exceptions.) If you want to find out about the prewar efforts to qualify at Indy by the French Schell Maserati team, there is an excellent chapter on Lucy O’Reilly Schell. However, if you are looking for information about the Lucy Schell Maseratis at Indy after the war when they had been sold to U.S. teams and drivers, it will not be there in any detail, but the efforts of the all-Italian Scuderia Milan in 1946 are well covered. The Cunninghams at Le Mans are not mentioned although since the 1921 Le Mans was an open wheel event, the Duesenberg victory is very well detailed and entertaining.

This is not meant as a negative criticism, but only to alert the potential buyer of the scope of the book, which is unusual but makes the story much easier to navigate.

If Zana is not familiar to most of our readers, he should be. A longtime reader of VeloceToday, Aldo has kept us on the straight and narrow through his decidedly knowledgeable comments. Recently he contributed an article on the first Formula Junior race at Monza. He lives in Milan, studied for a PhD in theoretical physics while writing for Autosprint magazine. He is the author of motoring books including two titles for the AISA (association of motoring historians.)

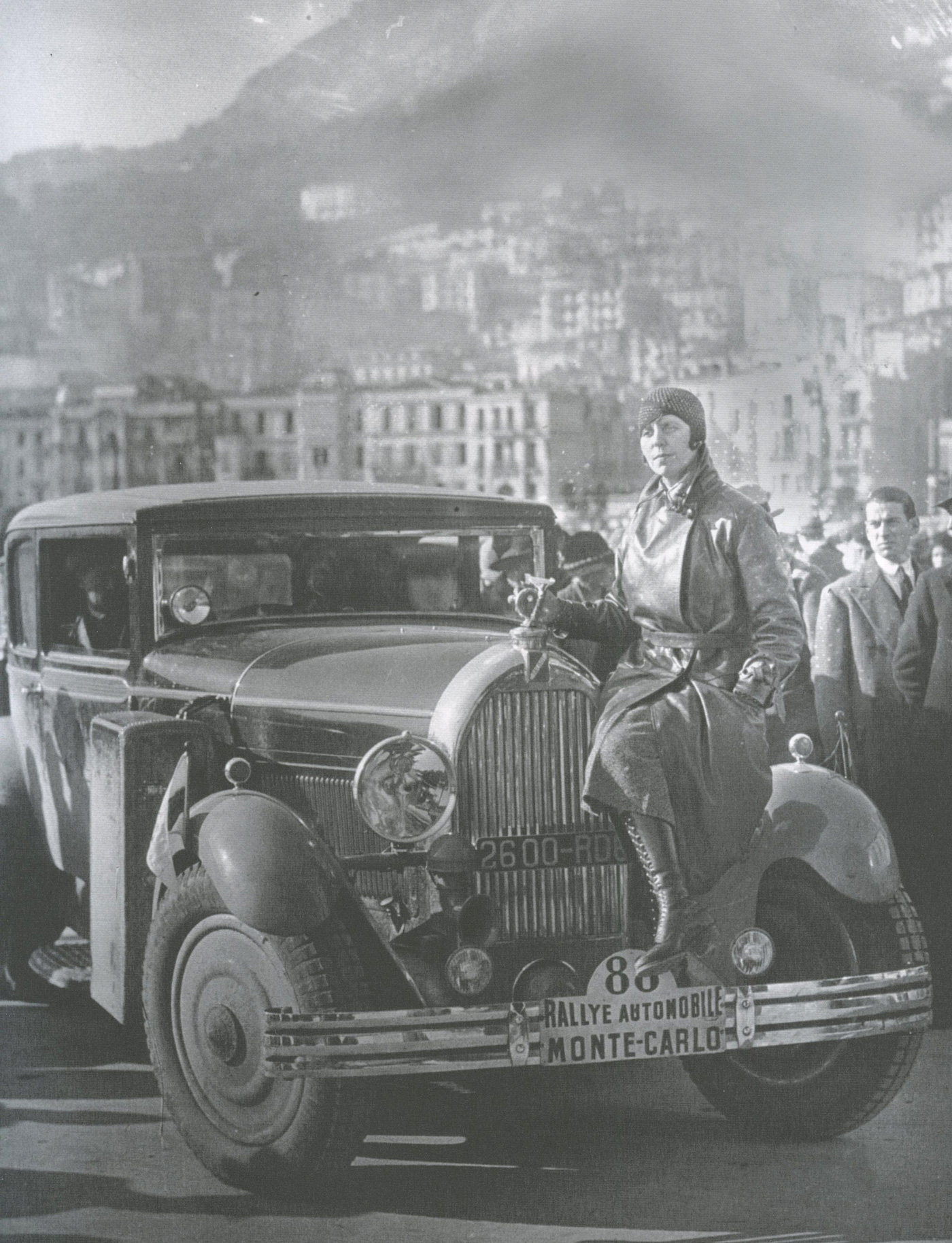

The driving force behind the Schell Maserati team in 1940 was an American in Paris, Lucy O’Reilly Schell (1886-1952), seen here with her Talbot at the conclusion of the 1930 Monte Carlo Rally.

Zana also has a family home in Connecticut, is fluent in English and is more than qualified to write a history of what is primarily an Italian-American story (the French are basically out of the picture after Bugatti’s 1923 Indy entry.) Zana includes race reports and commentaries from both sides of the pond, along with his own criticism. He finds that the attitude of the Europeans toward both Indy and Monzanapolis frustratingly superior, leading to repeated failures. In a telling anecdote, Zana relates how in 1946 Indy veteran and Novi driver Duke Nalon qualified almost as fast with a 1500cc 4CM Maserati than did rookie Luigi Villoresi in a full blown 3 liter 8CM Maserati, much to Villoresi’s discomfort. “He [Villoresi] understood that maybe the skill of the American drivers meant something on the Speedway,” Zana relates. In multiple attempts at the Brickyard, Ferraris failed to qualify in all but one, Ascari’s 1952 effort, which ended in a still mysterious rear wheel fracture and Zana tries to determine the real reason the spokes broke on Ascari’s Ferrari. Ascari was never really in the running, and clearly the Italians consistently underestimated the demands of racing at Indianapolis.

After the French Maserati failure came the Italian Maserati attempt in 1946. Zana thinks the Italians had a superior attitude which did not help them understand the realities of Indy car racing. Scuderia Milan consisted of from left Varzi, Villoresi,Corrado Filippini and owner Arnaldo Mazzucchelli.

An exception to the exceptions was a description of Rudolph Caracciola’s almost fatal 1946 practice accident in the Thorne Special, including speculations at the time that the car may have been sabotaged by someone not too thrilled with a German driving at Indy right after the end the war. In a similar vein, Zana tells of how in 1921, Jimmy Murphy defeated the French at their own Grand Prix with the all-American Duesenberg, but was ignored at the ensuing awards banquet.

Alfa Romeo offered to help unload and transport the American Indy cars to Monza as well as provide some mechanics.

By mid-book, he is ready to take on the main theme of his title, Monzanapolis, in depth, using Italian, British and American sources. Zana is not afraid to tackle the manner in which the new Monza oval track was built as he writes: “Sixty years have passed. One still questions why Luigi Bertett and the managers of the Automobile Club di Milano agreed in 1955 to have the new high speed ‘oval’ built at the Monza Autodrome.” It was poorly designed, poorly constructed, and everyone hated it. (Strangely enough, as Zana points out, the same was said of the Vanderbilt Cup track construction for the 1936 races; it was rush job that few were happy with.) Furthermore, at least as far as this reviewer can determine, with Monza, the idea of both the oval and of a race with Indy cars was not thoroughly addressed with the major Italian and European constructors beforehand, and if so their concerns were ignored.

The boys from Eurie Ecosse were the only European team (we say that with hesitation) to qualify cars for the 1957 Race of Two Worlds. None retired and in the end, did very well as sports cars.

The first 1957 race (to be paced by an Alfa Giulietta Spider, woefully underpowered for the task!) began at 12 noon, Italian lunch time, and what crowds there were did not appear until several hours later; not exactly a brilliant decision. Zana recounts the problems of the driver’s union, the UPPI (Unione dei Piloti Professionisti Internazionali.) Established to help protect driver’s images in light of the 1955 Le Mans disaster and the Mille Miglia fatal incident, killing nine onlookers, the union decided to boycott the first race in 1957, and the press, including Floyd Clymer in the U.S., took out their frustrations on Juan Manuel Fangio who, being a four time world champion, was the most prominent member. Only Jean Behra ignored the ban, attempting to quality two different Maseratis, but in the end failed to start with either won. Zana wonders how much money was offered to the Orsis to make at least some sort of a showing.

The Americans won, the race was a letdown, and yet, despite or perhaps because of the attention, both races brought a fresh new view of a different kind of racing not only to Italy but to all of Europe. The Americans impressed everyone not only with their speed but bravery, stamina, and courtesy.

The only foreign entries in the 1957 event were the three hardy Ecurie Ecosse D Jags just off their win at Le Mans. These of course were sports cars and not up to the speeds of the Offys, but they all finished and got a lot of great publicity.

The next year, Maserati and Ferrari took the bait and rather hastily prepared cars for the event, though again the superiority complex of the Italians took hold and the cars were not seriously developed. Yet they not only put on a good show, but a brave Luigi Musso garnered pole position with the horrid Ferrari 412. Phil Hill and Mike Hawthorn drove with Musso during the race helping the car place third overall on the aggregate. Moss had only a slight chance with the Maserati El Dorado until the steering broke. He was lucky to escape with his life and uninjured. It was the fastest race in the world up to that time.

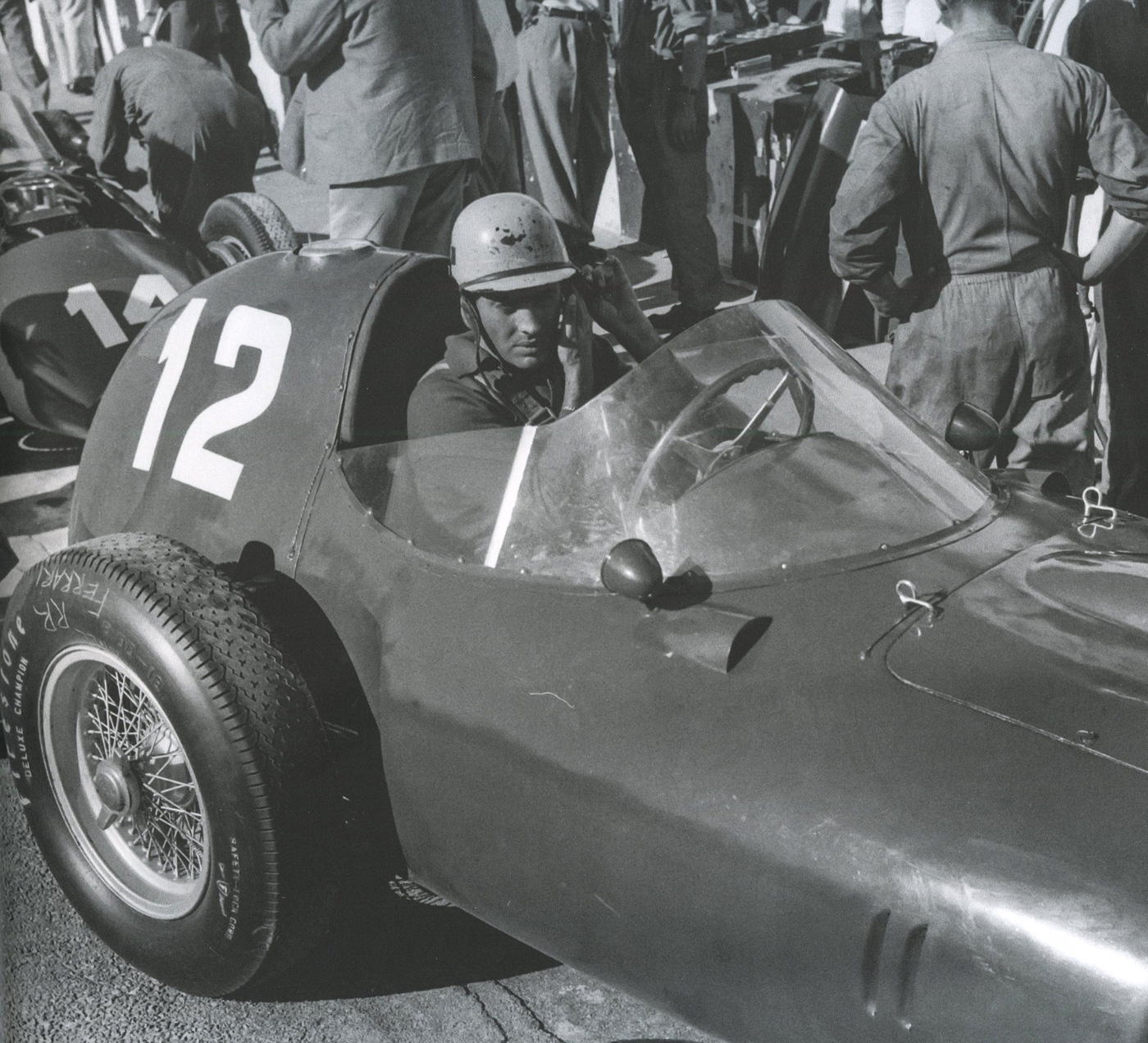

Brave, brave Luigi Musso captured pole position in the Ferrari 412, but was assisted by both Phil Hill and Mike Hawthorn to get the car to finish third overall.

A third event in 1959 might have seen real racing between the two worlds; the Ferraris would have had a chance to learn a bit more, and perhaps even the Coopers might have entered, though the horrific pounding might have been detrimental to the lightweights. It was a another promise unfulfilled. The planned event for 1959 was cancelled in January, presumably because of “…the negative attitude of the FIA and USAC towards modifying their formulas to create something acceptable to both ruling bodies.”

Two worlds, indeed.

Buy the book, whatever world in which you may live. Here’s how:

Monzanapolis The Monza 500 Miles, The endless American-European challenge

By Aldo Zana

ISBN 978-88-96796-51-1

Format: 23×28 cm

Hardback

280 pages

Over 300 photos, B/W

Italian and English versions € 49,90

Order Here

To avoid confusion, and while Fangio must have mentioned “the fine mess” to Rodger Ward, not Roger, the driver next to him is actually Johnny Parsons, the 1950 Indianapolis winner.

Thanks Willem! And it is corrected.

In 1952 Ascari’s wire wheel collapsed at the end of the wire wheel era. Wire wheels had been failing at the Speedway in 1951 also, and magnesium wheels were replacing them mostly thereafter.

Charley Goddard

Muncie, IN

Villoresi was among the fastest during the 1946 Indy 500. He had magneto trouble which delayed him over 30 minutes. His finish behind the winner was approximately the same.

There was nothing mysterious regarding Ascari’s wheel failure at the 1952 Indy. The exact same thing had happened to Wilbur Shaw’s Maserati in the 1941 500. In the 50s, wire wheel failure was almost common in Ferraris in U.S. road racing, as well as in the Carrera Panamericana.

At the 1952 500, Ferrari was offered Halibrand Wheels, but they claimed the wheels would upset the steering geometry.