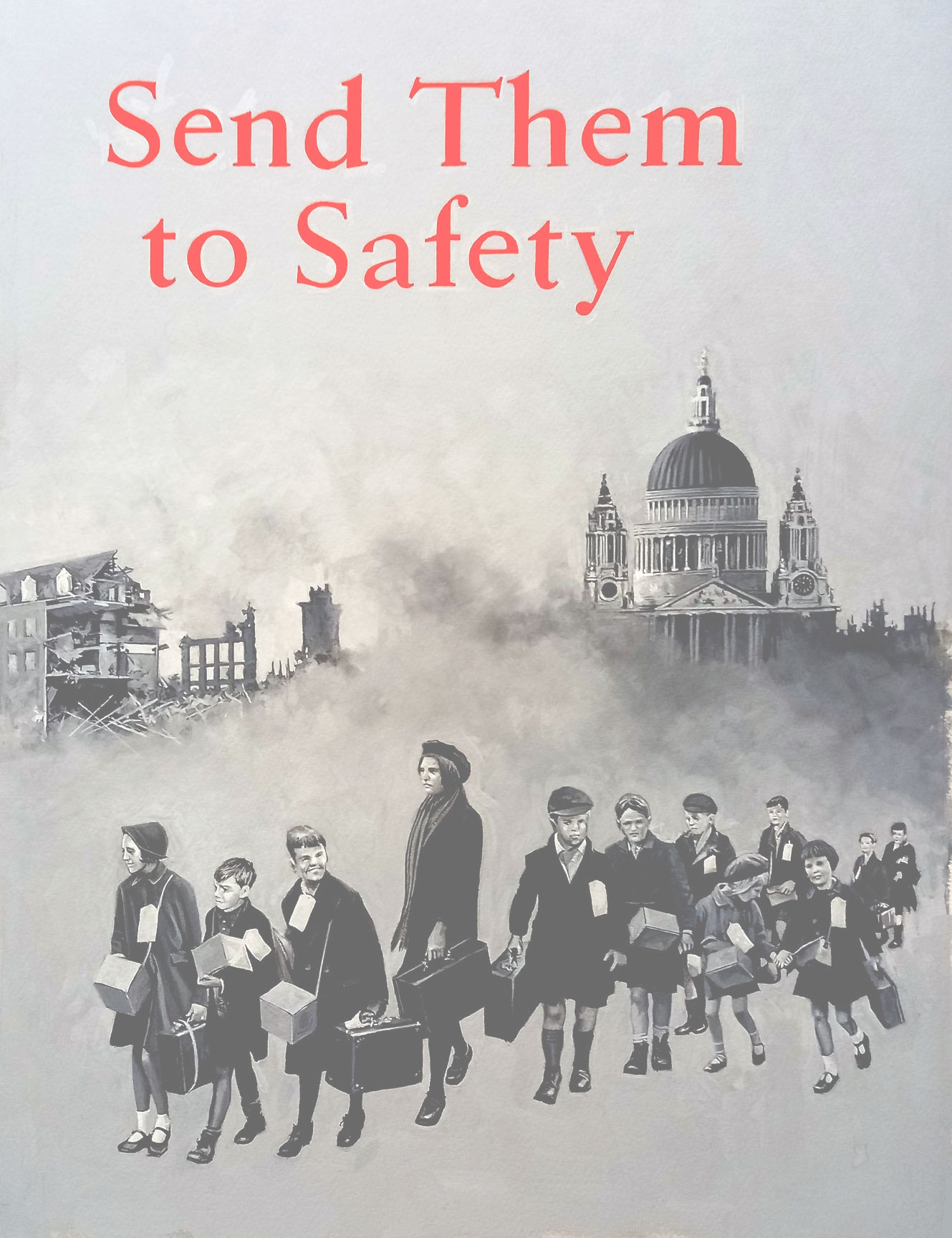

Rodney Diggens is known for his dramatic paintings of automobiles and aircraft. But before he found success as an artist, Diggens experienced the bombing of London and the evacuation of the children to the safer countryside. This is his painting, and this is his story.

Editor: It’s hard to imagine that there are still many about who are old enough to vividly remember the war years in the UK. But Rodney Diggens lived through those years and in fact participated in one of the great social experiments ever – moving out thousands of school children from London to the countryside where they would be safe from German bombing. He was part of the biggest migration in British history. Augmenting his story is information gleaned from the Imperial War Museum’s website.

Story and art by Rodney Diggens

Back in 2015, VeloceToday’s editor Pete Vack came searching for that fellow Diggens, and in particular an illustration of Jean-Pierre Wimille. Seems that he remembered my work for the British magazine, Thoroughbred and Classic Cars. And that was many years ago, in the 1970s!

Well, of late, I’ve been taking a more leisurely approach to life. Painting mostly for my own amusement, slipping back in time hoping to recapture those wonderful days of yore. And thanks to VeloceToday I’m getting lots o’ that. This time around, the editor asked me to talk about my life as an artist.

London to Dorking, Surrey

Volunteer evacuation for me and my brothers came in three separate installments. First was the beginning of WWII in September of 1939, Europe was well under Hitler’s thumb at this stage and we were sent off to Dorking in Surrey, Mum included. London would be an obvious target of course and it was clear that an invasion was imminent by what was happening on the French coast and the government feared that London would be bombed in advance. But the phony war lasted only a short time and thanks to that gallant ‘Few’ the invasion never happened, so many children returned to London.

London to Gressenhall, Norfolk

But the government was asking that children stay away from London anyway. Despite this we returned to London in late 1939, only to be sent off once more in 1940 to Gressenhall in Norfolk to lodge with an accommodating family in a very large and impressive house; well it was compared to our small terraced house in London.

It was on the way to Norfolk that I have clear memories of a column of small children, appropriately labeled, carrying small suitcases, gas masks slung over their shoulders, walking to the Elephant and Castle station, elder brother Keith and I among them as we made our way from London to Dereham.

I was only three or four at the time, but still have memories of a ring of uniformed soldiers with me being tossed from man to man, great fun for them but I don’t think I was enjoying it as much as they were. But never mind, big brother (a mere year older) Keith came heroically to the rescue and it all ended in good humour.

Gressenhall to North Green, Suffolk

I’m not sure how or when it exactly came about but arrangements were made for Mum and younger brother Trevor to travel down to a village in Suffolk called North Green near Parham, where a small cottage had been made available. Later, Keith and I were driven down to Suffolk to join them. I remember the car well, a supper blue and black Austin 12 complete with chauffeur. Don’t think he was wearing peaked cap and gauntlets but memories can play tricks at times like those!

The facilities at the cottage were, to say the least, very primitive. How mother coped I can’t imagine, but cope she did! No electricity, no gas and no water; that was drawn from a communal hand operated pump on the village green. Imagine a cold winter’s morning the ground covered in snow and you’ve been chosen to be the day’s water boy! Wearing just pajamas and wellies sent out to collect the morning’s supply, pitcher and bucket to hand! We did ‘lend a hand,’ as much as three small children could of course, and during harvesting I recall the combined harvester, pulled by a team of horses on occasion, working in ever decreasing circles leaving a small area of standing corn where the rabbits had collected, to be beaten out by the farmers and their dogs! We’d often return to the cottage with at least one unfortunate rabbit.

Cooking was on a small oven heated by mentholated spirits. Toilet facilities were housed in a small wooden shed in a corner of the garden! Unimaginable by today’s standards but cope she did!! A commonly held myth at that time was that evacuees from London were considered to be dirty, unwashed and louse ridden. Completely untrue of course and we three were often to be seen in a defensive circle fending off hostile locals! Custer’s last stand comes to mind! We stood our ground though and were, eventually, accepted into the local community. We all started our education there and were enrolled into the local junior school in Parham village. That strengthened our acceptance and we felt, at last, true ‘Suffolkers’. When we eventually returned to south London we sounded more like Suffolkers than Cockneys!

Text from the Imperial War Museum: Evacuees and their hosts were often astonished to see how each other lived. Some evacuees flourished in their new surroundings. Others endured a miserable time away from home. Many evacuees from inner-city areas had never seen farm animals before or eaten vegetables. In many instances a child’s upbringing in urban poverty was misinterpreted as parental neglect. Equally, some city dwellers were bored by the countryside, or were even used for tiring agricultural work. Some evacuees made their own arrangements outside the official scheme if they could afford lodgings in areas regarded as safe, or had friends or family to stay with.

Soon after our arrival at Parham, the 390th Bomb Group USAAF 8th AF came to our little village. Known as ‘Framlingham’, after the nearest prominent town, it was just a stone’s throw from North Green. Life changed yet again and the Americans became an integral part of village life. One, Melvin R. Blanchard, left waist gunner on B17F Flying Fortress ‘Cabin in the Sky’ 571st Squadron became a regular visitor to that small cottage at North Green. To say that life changed is, as they say, putting it mildly! It’s worth considering here just what life was really like during that period. Especially for a young mother with three lively young boys running her ragged! Father away fighting the foe serving with the 1st Royal Tank Regiment in North Africa and on into Italy. I finally met my father when I was nine; as a complete stranger, I had no memory of him whatsoever. That he survived at all is remarkable; many didn’t.

Like London, the airbase was a prime target and there were attacks. Aircraft had a number of accidents too. One unfortunate aircraft lost height on takeoff, fully loaded and destroyed the small chapel in Parham. I remember looking at the remains a couple of days later, all that remained was the font! As I recall nothing of the building was left standing and amidst the scattered rubble stood that poignant and isolated image, not a scratch to be seen!

My rendition of aircraft of 517 Sqn including ‘Cabin’ in the foreground, returning to Framlingham in 1943.

We remember fondly those Christmas parties the kids were invited to hosted by the 390th. I’m not sure if they were held in the village hall or at the airfield but I sure do remember them! Of course the elders were invited to other social events too and rumor had it that my Mum, also known as ‘Rita’, was the station’s ‘Jitterbug Queen’ and who could blame her, for it was a welcome break from that isolated cottage devoid of all those home comforts we all enjoy to-day. Activity on and around the airfield was intense of course and to witness the aircraft setting off on yet another mission was for us kids hugely exciting! We had no real understanding of what we were witness to back then, it’s only on reflection that the reality hits home. I will never forget those brave young Americans who sacrificed so much, hate to think of the consequences had they not been there.

I tried looking for the Blanchard who survived the conflict a while back. The 390th museum in Tucson Arizona were very helpful and replied with at least a dozen Melvin R. Blanchards but to no avail. The 390th museum in Suffolk too were really helpful and I have a full record of Blanchard’s missions. My two years National Service (1956-1958) were spent with the 1st Royal Tank Regiment also, my father’s doing I’m quite sure.

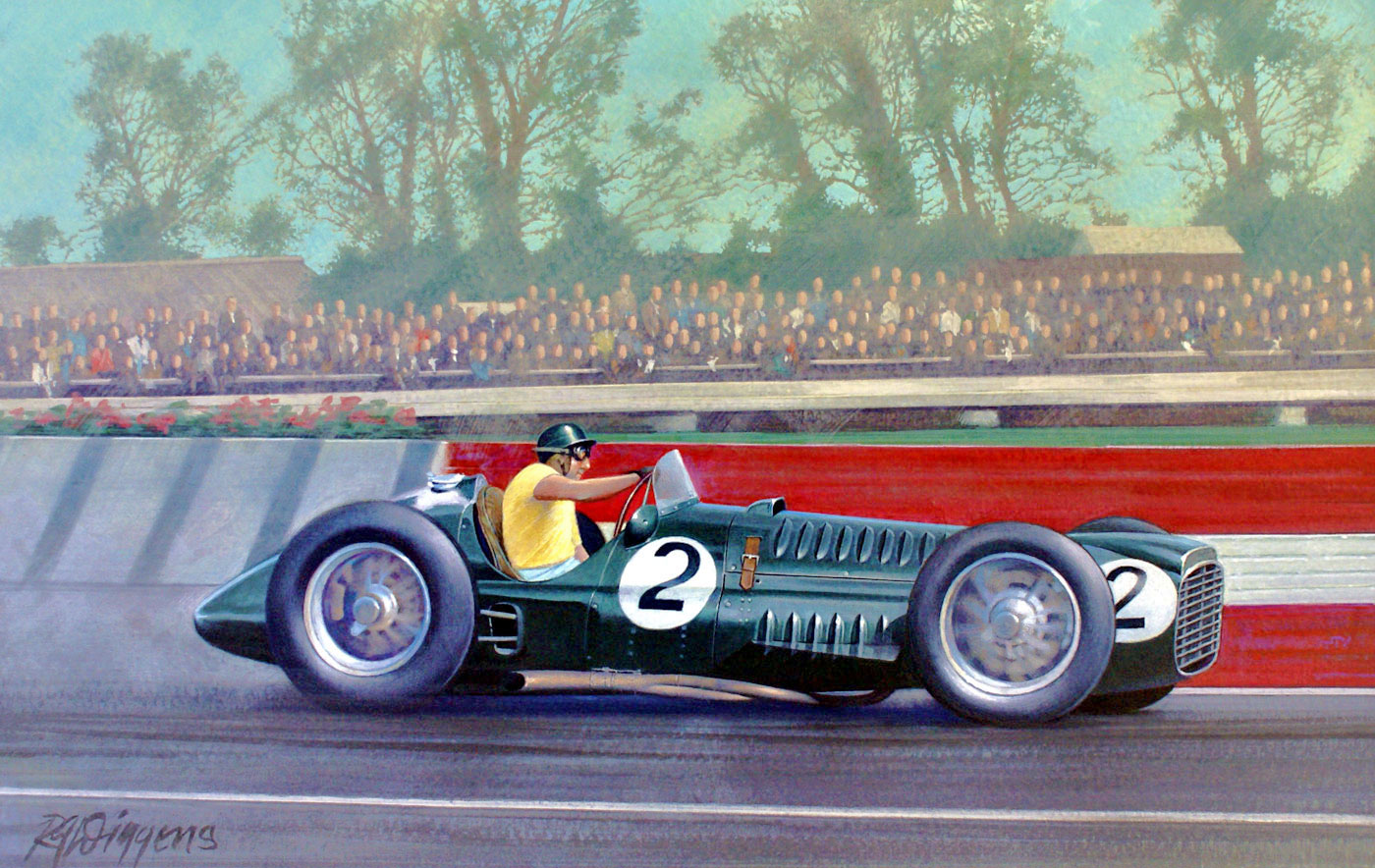

Art we remember. Rodney Diggens would attend the 1953 British Grand Prix and later on would create this vibrant portrait of the V16 BRM. “I first saw the BRM V16 at the British Grand Prix meeting at Silverstone in 1953. Fangio and Wharton were driving and I can still hear those two howling passed the grandstand to this day!” Diggens would have much of his automobile art published in the British magazine Thoroughbred and Classic Cars.

Postscript: A magazine I subscribe to is The Oldie, ideal reading for those who chose to ‘Grow Old Disgracefully’ the title for one of the magazine’s regular supplements.

One particular item that caught my eye featured Rolling Stone’s founding bass player Bill Wyman, by Christopher Sandford. It tells the story of Wyman’s time with the Rolling Stones and includes his early childhood, spent living with his grandmother in South London during the Blitz, apparently under the name of William Perks. Unlike my two brothers and I, it seems he remained living there for the duration but the conditions that he was living under reflect our own experiences to a tee; no running water, no electricity, food rationing and the toilet in ‘a little wooden hut in a corner of the garden’!

I remember returning to London on a couple of occasions during that time to visit Grandma and Grandad, staying with them in their home in Peckham, south London. I recall too the eerie wailing of the air raid warning as we ran to the shelter in our pyjamas! The shelter was situated in the grounds of the British Lion Laundry where Grandad worked. I can still see the rooftops and chimney pots silhouetted against the flames of other burning buildings as we hurried to the safety of the shelter.

Seems odd writing to the editor of an on-line motoring magazine about the London Blitz, but when you set the ball rolling I’m afraid my brothers and I started reminiscing about old times and reliving those events long gone. The owner of that cottage at North Green has turned it into an amazing multi roomed mansion!

Next: Part 2 Apprenticeship of an Artist

Very interesting early years Rodney. Looking forward to the next instalment of the life of a fellow aviation and motoring artist although I am just slightly later than your own experiences. Growing up in the North we hardly knew there was a war going on.

Many thanks for that excellent article.