By Roberto Motta

Photos courtesty of Roberto Motta, Dino Brunori and Alessandro Nassiri © Archivio Museo Scienza

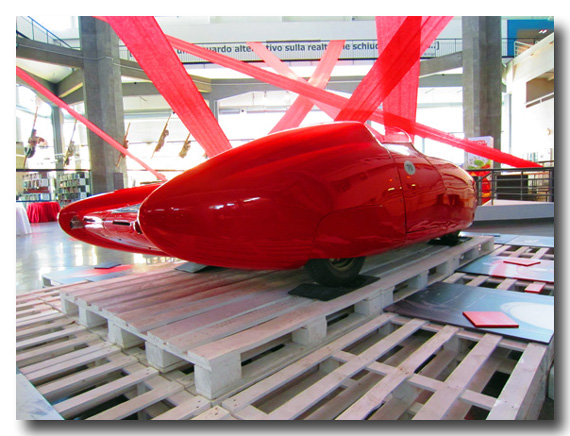

As we have seen, (Read Nardi at Le Mans Part I) despite the early retirement of his car in 1954, Damonte was still eager to compete with a Nardi at Le Mans. At some point in 1954, the engineer-architect, pilot and aircraft enthusiast Carlo Mollino was taken by the lines of Damonte Le Mans OSCA. Mollino had been hired by Damonte to redesign his personal apartment and the two shared an interest in cars. Using a photo of the OSCA as it appeared in a magazine, Mollino began to sketch out an idea for an aerodynamic body that would not cover a racing car chassis, but instead, a chassis would be constructed to conform to the streamlined body. Mollino became part of a new project to create a new car for the 1955 Le Mans. It would become known as the DaMolNar (Damonte/Mollino/Nardi Bisiluro.)

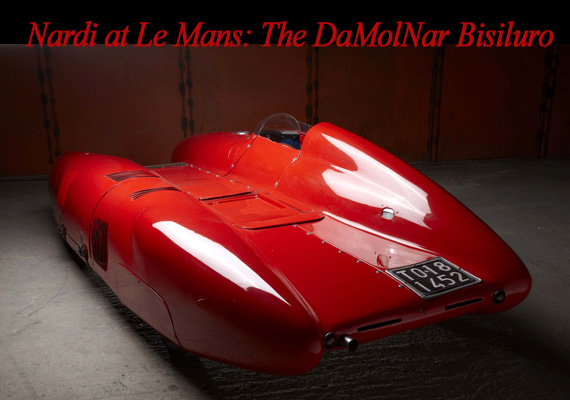

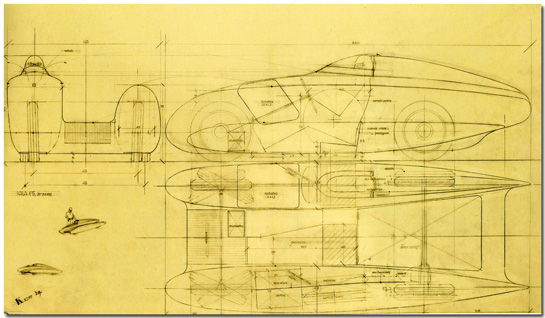

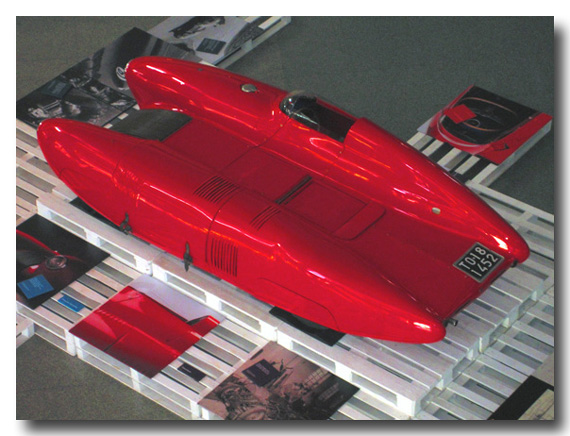

Mollino first designed a car with an aerodynamic nose, no radiator, modeling it like a thin airfoil and then began to add essential elements. The final design was a totally asymmetric car, consisting of two separate nacelles.* The left side contained the engine and transmission; the right side was dedicated and designed for a driver of small stature (less than 5 foot 7 inches).

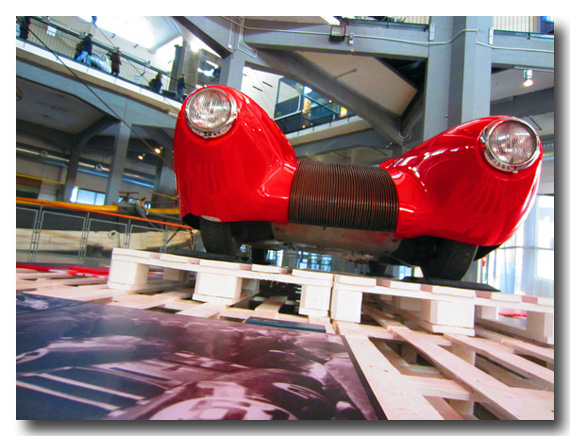

The lack of space required a special steering wheel designed by Mollino and crafted by Nardi, oval at the bottom to facilitate the inclusion of the rider’s legs, as well as to lower the steering column. Among the aerodynamic refinements of the car is the rearview mirror that is made retractable by an internal lever in order to eliminate possible drag.

To improve the efficiency of the brakes, the car was equipped with an ingenious aerodynamic brake consisting of two-levels of flaps, positioned near the center of pressure, i.e. in the central part of the body between the two nacelles. When opened, they were designed to slow the car down evenly and relieve the stress on the normal drum brakes. The system was controlled by an additional foot pedal located on the left of the car. The Mercedes Benz 300SLRs also used an airbrake that year for the same reasons.

The aerodynamics of the car was fine-tuned by the shape of the radiator, refining the front bodywork, the wheel fairings, and the body pan. In addition, the center section of the car was actually an airfoil; different profiling of this wing allowed Mollino to alter the negative lift. The radiator was an innovation, consisting of brass pipes with a rectangular cross section, bent to conform to the body and dissipating heat via the airflow over the tubing. Mollino was far ahead of his time, creating a car with such great attention to aerodynamics that it would not be until twenty years later that F1 cars like the Lotus began incorporating such techniques with the ground effects.

The entire body was the work of the artisans of CA.MO. Rocco Motto, made of aluminum with a thickness of 9 / 10 of a millimeter, joined together by welding with borax.

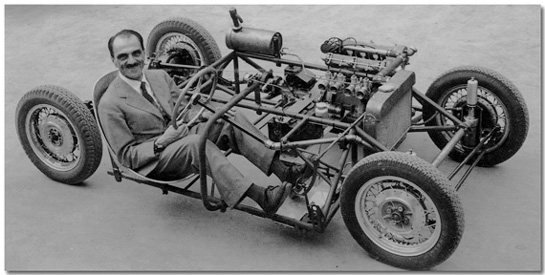

The chassis as tested without the body. Note the standard radiator, test fuel tank, Appia suspension and round steering wheel.

Nardi took up the challenge of this strange idea of creating a chassis after the body rather than vice versa. The preparation of the frame reached the stage of rolling chassis in February ’55. In late spring the car was mechanically complete. The chassis was a unique as the body. Nardi made use of the simple but effective Lancia Appia suspension at the front. A sturdy tubular type frame was then constructed to accommodate the driver and engine; the driveshaft was connected to a modified Fiat 1100 rear end. Rear suspension consisted of elliptic springs and trailing arms…light and suitable for the smooth track at Le Mans.

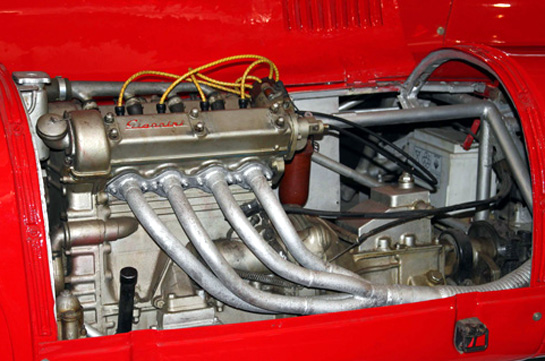

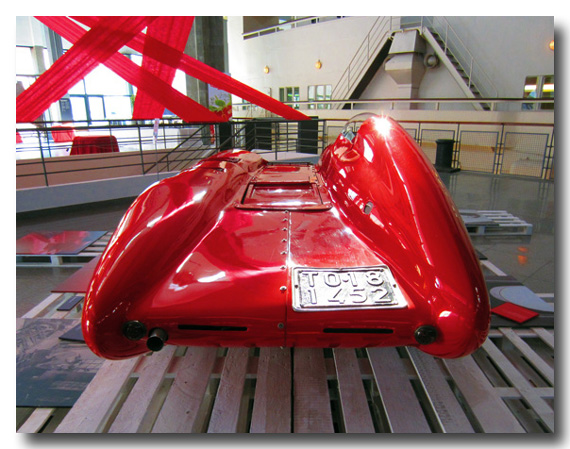

The engine was installed on the left side of the car. The Giannini G2 4-cylinder 750 cc was mated to a 4-speed + reverse gearbox and differential. Designed by Charles Roman Gianini, the unit was inspired by the engine used in ’53 and ’54 Moto Guzzi for their GP bike. A bore and stroke of 57×72 mm gave a displacement of 734.53 cc and with double overhead camshafts driven by gears, was able to deliver about 60 bhp at 7000 rpm. In its most evolved form, powered by a pair of Weber 32 carburetors DCO3, the G2 was rated at almost 70 HP. However, during the race at Le Mans, Nardi preferred to use four Dell’Orto SS 25 carbs in separate trays, which allowed the engine to produce 55 hp at 6000 rpm and reduce fuel consumption by 10-15%. In this configuration the vehicle could still exceed 215 km per hour (134 mph).

The Bisiluro weighed 400 kilograms with a wheelbase of 1900 mm, front track and rear respectively 1195 and 1135 mm. It used 4.00×15″ tires mounted on spoked Nardi Crosley wheels. Without a body and running a ‘normal’ car radiator, it was subjected to intense road testing in early May, a month before the 24 Hours of Le Mans on 11 June. The test revealed some work to be done.

The Bisiluro weighed 400 kilograms with a wheelbase of 1900 mm, front track and rear respectively 1195 and 1135 mm. It used 4.00×15″ tires mounted on spoked Nardi Crosley wheels. Without a body and running a ‘normal’ car radiator, it was subjected to intense road testing in early May, a month before the 24 Hours of Le Mans on 11 June. The test revealed some work to be done.

In search for proper weight distribution, the power unit was set back 350 mm which allowed a better centralize mass and achieved a lower, tapered shape of the fuselage on the left. The lines of the car were improved by mounting the aerodynamic radiator, and replacing part of the body.

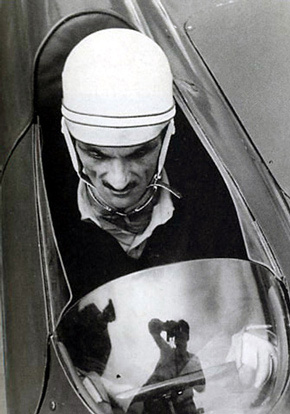

The extremely aerodynamic body shape made the car very sensitive to quick movements and the driving style required a great deal of attention. The changes of direction must be made slowly, so as not to upset the balance. Otherwise the consequences would be disastrous.

The Bisiluro at Le Mans. Not the added airfoils over the radiator to force air around the brass tubes.

At the end of the final development and before the race at Le Mans, the Bisiluro was tested on the track at Monza where it reached the 217 km per hour.

The team loaded up the Bisiluro on a trailer towed by Damonte’s Fiat 1100 sedan and off to the epic event they went. As usual, scrutineering was difficult.

After a quick consultation with the ACO, who now demanded that the car have a rudimentary passenger seat, Nardi decided to remove the aerodynamic brake and put a folding stool in the compartment reserved for the airbrakes. It satisfied the organizers but the removal of one of the structural cross braces made the chassis even more difficult to handle.

Registered with the number 61, the crew consisted of the French-Italian Roger Crovetto and Mario Damonte with reserve drivers Gino Munaron and Paul Graunet. During practice, the Bisiluro proved once again capable of exceptional performance beating all competitors in the class, as well as some cars of greater capacity.

In Dino Brunori’s book “Nardi, a fast life”, Gino Munaron recounted for Brunori what it was like to drive the Bisiluro at Le Mans. He drove it during practice, and immediately was made aware of the noise of the engine, sitting beside him. After a while there was less noise as “you soon found yourself deaf in the left ear.” It was fast, and he was impressed with the aerodynamics. But it was twitchy. “It was a continuous job trying to keep it going straight”, he recalled. The faster it went, the more difficult to control. He pulled into the pits and still clearly remembered the thought which crossed his mind. “Damonte will not have a quiet country walk on Saturday…”

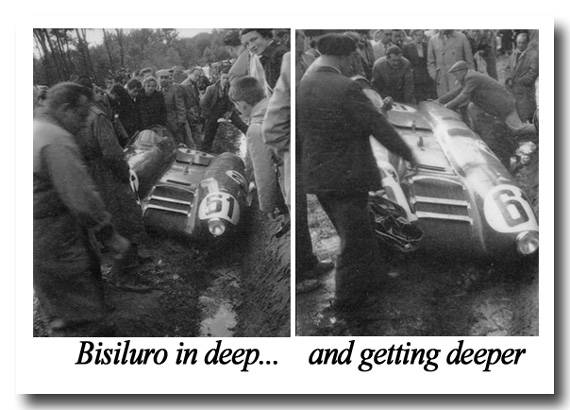

After just 148 minutes into the race, the Bisiluro with Damonte at the irregular wheel was passed by a Jaguar. Legend has it that Jag sucked the air out from under the Nardi, causing the Bisiluro to lose grip and spin off the road into a canal.

More likely, Damonte corrected too quickly and therefore lost control.

The team packed up and once again went home empty handed. But their troubles and the Bisiluro’s fate were overshadowed by the crash of the Levegh Mercedes which killed over 80 people.

Back in Italy, the Bisiluro was forgotten for years. But ten years later, in a very wise move, Enrico Nardi donated the car to the National Museum of Science and Technology ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ in Milan. There it remained, safe and sound for posterity.

From left, Fulvio Ferrari, Marco Iezzi (Curator of the Museum of Transport Department) and Napoleone Ferrari.

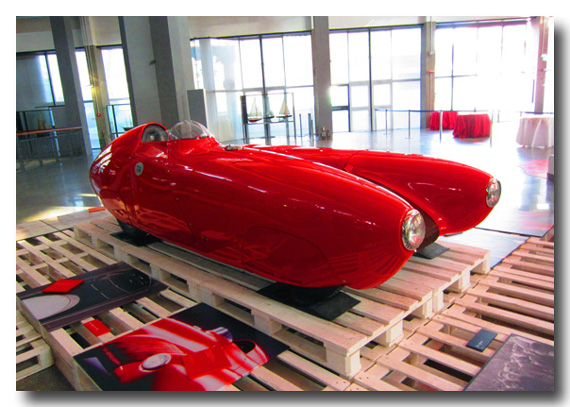

Recently, after a restoration, the Bisiluro DaMolNar was exhibited in the exposition “Carlo Mollino: Modern Way”, held at Haus der Kunst in Munich. Then, on January 21st, the Bisiluro returned to the Museum of Science and Technology ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ in Milan. The presentation was attended by Fulvio and Napoleone Ferrari, experts in the history of Mollino, and the Curator of the Museum of Transport Department, Marco Iezzi.

The Museum is housed in a monastery from the sixteenth century and contains an important cultural heritage on the history of science, technology, design and industry. The Land Transport Museum aims to highlight the vehicles and objects in this collection through exhibitions and loans with rotating temporary exhibitions at the Museum.

*It should be noted that although his drawing and notes never referred to similar TARF cars, Mollino must have been aware of the record breaking motorcycles built by Piero Taruffi, the first in 1948. However, the TARFs I and II were motorcycle derivatives and the engine was always with the driver.

A Walk Around the Bisiluro

In Italian

Come abbiamo visto, nella prima parte dell’articolo, e a dispetto del ritiro avvenuto nella Le Mans del 1954, Damonte è intenzionato a partecipare alla competizione del 1955, sempre con una vettura realizzata da Nardi.

Ad un certo punto del 1954, l’ingegnere-architetto, pilota e appassionato di aerei Carlo Mollino rimane affascinato dalle linee della OSCA utilizzata da Damonte a Le Mans. Nello stesso periodo, Mollino viene assunto da Damonte per ridisegnare il suo appartamento personale. I due condividono l’interesse per le auto.

Utilizzando una foto della OSCA apparsa su una rivista, Mollino inizia a disegnare un’idea per un corpo aerodinamico, che non sarebbe servito a coprire il telaio di auto da corsa, ma che avrebbe avuto bisogno di un telaio costruito su misura. Mollino entra così a far parte di un progetto per creare una nuova auto destinata alla Le Mans del 1955. Questo progetto diverrà noto con il nome di DaMolNar (Damonte / Mollino / Nardi Bisiluro.)

Mollino disegna una vettura dotata di musetto aerodinamico, privo di radiatore, poi ne modella il volume centrale alla ricerca di un sottile profilo alare. Il disegno finale rappresenta una vettura composta di una carrozzeria totalmente asimmetrica, costituita da due carlinghe distinte. La sinistra contiene il motore e la trasmissione, l’altra è destinata al serbatoio del carburante, posto davanti all’angusto spazio dedicato e concepito per un pilota di piccola statura.

L’abitacolo, dalle dimensioni minime, è corredato di un volante disegnato da Mollino e realizzato da Enrico Nardi, ovalizzato nella parte inferiore per facilitare l’inserimento delle gambe del pilota, ma soprattutto in grado di abbassare il piantone dello sterzo.

Tra le raffinatezze aerodinamiche della vettura, segnaliamo lo specchietto retrovisore che diventa retrattile tramite un comando interno, in modo da eliminare possibili resistenze aerodinamiche.

Per migliorare l’efficienza della frenata, la vettura è dotata di un ingegnoso freno aerodinamico composto da due alettoni piani, posizionati nelle immediate vicinanze del centro di pressione, ossia nella parte centrale della carrozzeria tra le due carlinghe.

Il sistema è comandato da un pedale aggiuntivo posto nella parte sinistra dell’abitacolo, il cui scopo è decelerare la vettura senza scomporne l’assetto, e alleggerire lo stress dei normali freni a tamburo.

L’aerodinamica della vettura è affinata dalla forma del radiatore anteriore che sostituisce la carrozzeria, dalle carenature delle ruote, e dal fondo che impone alla vettura una forma alare e introduce quei concetti di base che saranno ripresi solo alla fine degli anni ’70 sulle vetture di F1.

L’intera carrozzeria è opera degli artigiani della CA.MO. di Rocco Motto, ed è realizzata in fogli d’alluminio dello spessore di 9 decimi di millimetro, uniti tra loro mediante saldatura con borace.

Contemporaneamente, nell’officina di Nardi, proseguono i lavori di preparazione del telaio che raggiunge lo stadio di ‘rolling chassis’ nel febbraio del ’55. Nella tarda primavera la vettura viene completata meccanicamente.

Il telaio tubolare della vettura prende spunto da alcuni disegni della FIAT 1100 e della Lancia Appia, ma viene realizzato con tecniche aeronautiche e ha un peso complessivo di soli 50 kg. Nella parte sinistra della vettura viene istallato il propulsore 4 cilindri Giannini G2 da 750 cc e la trasmissione completata con un cambio a 4 rapporti + RM e differenziale.

Il propulsore, progettato dall’ingegnere romano Carlo Gianini, si ispira al propulsore impiegato dalla Moto Guzzi nel ’53 e ’54 per le proprie moto da GP. Caratterizzato da misure di 57×72 mm che gli conferiscono una cilindrata effettiva di 734,53 cm3, sfrutta una distribuzione del tipo bialbero con alberi a camme mossi da ingranaggi, ed è in grado di erogare circa 60 CV a 7000 giri. Nella sua forma più evoluta, alimentato da una coppia di carburatori Weber 32 DCO3, il G2 riesce ad erogare una potenza che sfiora i 70 CV. Tuttavia, in occasione della gara di Le Mans, Nardi preferisce utilizzare una versione meno spinta del propulsore, a vantaggio dell’affidabilità e della riduzione dei consumi.

La versione calmierata del propulsore prevede l’alimentazione con carburatori motociclistici Dell’Orto SS 25 a vaschette separate, che consente al motore di erogare 55 cv a 6000 giri e di ridurre i consumi del 10-15%.

In questa configurazione la vettura è in grado di superare i 215 km orari. Le sospensioni anteriori sono del tipo indipendente, mentre quelle posteriori sfruttano un assale rigido.

L’impianto frenante utilizza un circuito idraulico e 4 tamburi.

La Bisiluro pesa 400 kg, ha un passo di 1900 mm, carreggiata anteriore e posteriore rispettivamente di 1195 e 1135 mm. Poggia su pneumatici da 4.00×15” montati su cerchi a raggi Nardi-Crosley. Ancora priva di carrozzeria, e dotata di un ‘normale’ radiatore automobilistico, viene sottoposta a intensi collaudi stradali nei primi giorni di maggio, un mese prima di poter partecipare alla 24 Ore di Le Mans dell’11 giugno.

Dopo i primi test, per un miglior bilanciamento dei pesi in vettura e, nella ricerca della corretta ripartizione dei pesi, il gruppo motopropulsore viene arretrato di 350 mm rispetto alla soluzione iniziale. Questa modifica consente di centralizzare le masse e di ottenere una conformazione più bassa e rastremata della carlinga sinistra.

La linea della vettura viene affinata con il montaggio di un radiatore aerodinamico, realizzato dalla F.A.R.T., che sostituisce parte della carrozzeria.

La forma estremamente aerodinamica della carrozzeria, rende la vettura molto sensibile agli spostamenti e richiede uno stile di guida molto attento e impegnativo. I cambiamenti di direzione devono essere effettuati ‘lentamente’, in modo da non scomporre l’assetto della vettura. Diversamente le conseguenze sarebbero disastrose.

Al termine della definitiva messa a punto e prima della gara di Le Mans, la Bisiluro viene provata sul tracciato di Monza dove raggiunge i 217 km orari. Giunta a Le Mans, durante le verifiche pre gara, non viene ammessa alle qualificazioni perché è in configurazione monoposto.

Dopo un rapido consulto, Nardi decide di asportare il freno aerodinamico e di inserire un seggiolino pieghevole nel vano riservato alla paratia aerodinamica. Grazie a questo stratagemma, la Bisiluro rientra così tra le vetture biposto, e può accedere alle qualificazioni.

La partecipazione della Nardi-Giannini 750 Bisiluro alla 24 Ore di Le Mans è decisamente sfortunata. Iscritta con il numero 61 e condotta dall’equipaggio italo-francese Mario Damonte-Roger Provetto cui si aggiungono i piloti di riserva Gino Munaron e Paul Graunet, la Bisiluro si dimostra subito capace di prestazioni eccezionali sbaragliando ripetutamente tutte le concorrenti di classe, oltre ad alcune vetture di maggiore cilindrata, e registrando medie sul giro vicine ai 150 km orari.

Dopo soli 148 minuti di corsa, la Bisiluro viene superata da una Jaguar. Narra la leggenda che, risucchiata dallo spostamento d’aria provocato dalla vettura Inglese, perde aderenza e, dopo diverse piroette, termina la sua corsa capovolta in un canale ai lati della strada.

Più verosimilmente, il pilota della Bisiluro effettua una correzione troppo rapidamente e perciò perde il controllo della vettura.

Questa edizione della 24 Ore di Le Mans è teatro della più grave e spaventosa tragedia mai occorsa in una corsa automobilistica, con un bilancio finale di oltre 100 morti e un numero incalcolabile di feriti.

Tornata in Italia, la Bisiluro viene dimenticata per anni prima di essere donata, nel ’65, dalla Nardi al Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ di Milano. Più recentemente, dopo varie azioni di restauro, la Bisiluro DaMolNar è stata esposta nell’esposizione “Carlo Mollino. Maniera Moderna”, tenutasi all’Haus der Kunst di Monaco di Baviera e lo scorso 21 gennaio è stata riportata nelle sale del Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ di Milano.

Alla presentazione hanno partecipato Fulvio e Napoleone Ferrari, esperti della storia di Mollino, e il Curatore del Dipartimento Trasporti del Museo, Marco Iezzi.

Il Museo ha sede in un monastero del Cinquecento e raccoglie un importante patrimonio culturale relativo alla storia della scienza, della tecnologia, del design e dell’industria.

L’esposizione della Bisiluro rientra tra le azioni di valorizzazione della collezione Trasporti Terrestri intraprese dal Museo, che mira a mettere in luce i veicoli e gli oggetti di questa collezione attraverso prestiti a importanti mostre e, a rotazione, esposizioni temporanee al Museo.

I really love the Italian cars and their people.

Alfredo.