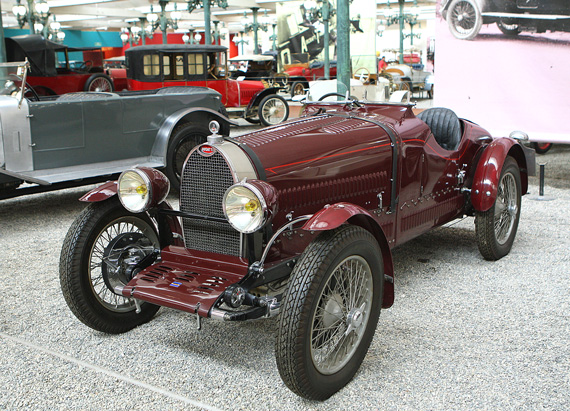

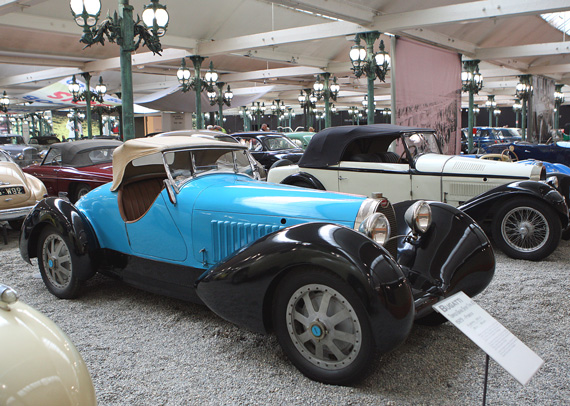

This 1929 Bugatti T35B was Fritz Schlumpf’s personal car in which he regularly used to compete in various hill climbs.

Bugattis at the Schlumpf by Jonathan Sharp

I must have first become aware of the Schlumpf collection back in the late 1970s, when stories started to appear in the British daily newspapers following the discovery of a load of old cars that had been hidden in an old woolen mill in Eastern France. From that moment on I had vowed to visit it one day. A family motoring trip to Lido di Jesolo in Northern Italy had brought me to within 30 kms of Mulhouse back in 1984, but the call of the sun, sand and pasta proved to be more popular for the rest of the family than a visit to a dusty old car museum. It was not until October of last year that I was at last able to tick the “Visit the Schlumpf Collection” box on my bucket list.

So what is my impression of the National Automobile Museum in Mulhouse, as it is now called? (VeloceToday will refer to the National Automobile Museum in Mulhouse as the “Schlumpf”, however incorrect, it is short and meaningful.)

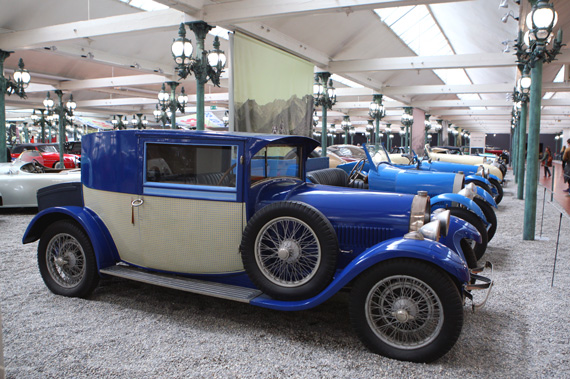

Well to start with the contents, which are amazing. I have never and probably will never see as many Bugattis all in one place again. The Museum however is much more than just a collection of Bugattis. The Museum display encompasses early French cars from marques that I had never heard of, let alone seen. There are German and Italian cars, a smattering of English cars with Rolls-Royces being very popular. They are not all luxury cars and whilst the collection famously holds three Bugatti Royals it also contains plenty of the more bread and butter type of cars-some more well-known than others.

The racing cars in the collection are displayed in a separate hall. (This will be presented next week in VeloceToday) As you enter the Racing Car hall you are greeted by a field of blue and red with a smattering of white with most cars being from the period when you knew the nationality of the car by the color of the bodywork.

Having recently visited the two Ferrari museums in Italy, my initial thoughts were that the display was that it was perhaps a little bit two dimensional, with most of the cars being displayed side by side; the display halls are illuminated by 900 cast iron street lamps copied from the Alexandre the 3rd Bridge in Paris. On the day we attended, the weather was not great so the main hall was a bit dark. This made the photography harder BUT having now had time to reflect on what I had seen my opinion has changed. Given the sheer numbers of cars that are on display, to display them in the style of say the Casa Enzo Ferrari Museum in Modena, on plinths scattered artistically around the display hall, you would need a building larger than the Houston Astro Dome. I had also failed to take into account the building itself. It is not a modern architect-designed purpose-built Museum, but an old woolen mill built in 1880.

So if the collection is on your bucket list, then you should go. I do not think you will be disappointed. The museum is a short tram ride away from the center of the town. The town has many hotels but my wife and I stayed at a beautiful Bed and Breakfast establishment right in the middle of the town by the name of Maison Mondrian. A very modern and stylish place, impeccably clean and located above the owner’s delicatessen which was stuffed with many an epicurean delight, many of which ended up in the back of our Giulietta to be enjoyed at home. One word of advice – if you are going to be in town over the weekend may I suggest you book a restaurant table before you arrive; all the Mulhouse residents seem to go out to eat at the weekend.

Bugatti Biplace: This phaeton bodied two-seater Bugatti was created by Ettore in 1931 to be used in the factory and his home. At least three were built. Its 1.2 CV output is produced by a 36 volt electric motor.

This 1913 15CV 4 cylinder torpedo bodied Bugatti Type 13 was found in a shed near the salt marshes between Le Pouligen and Le Croisic. The high quality of the materials used in construction preserved her against the ravages of the salt.

The French aviator Roland Garros was much taken with the Bugatti T16 so ordered one from Ettore. As a tribute to Roland his name was used for all models. This example is listed as a 1912 100CV Bi place Sport; the 5 liter engine gives the car a top speed of 160 kph.

The Bugatti Type 17 was a more spacious version of the Type 13, designed for the sporting motorist and fitted with a 1368 cc 18CV 4 cylinder engine. This example dates from 1914. The boat tail bodywork is made from mahogany.

The Bugatti Type 19 was a prototype built with the idea of the car being built under license by another manufacture. Peugeot produced the model as the BB.

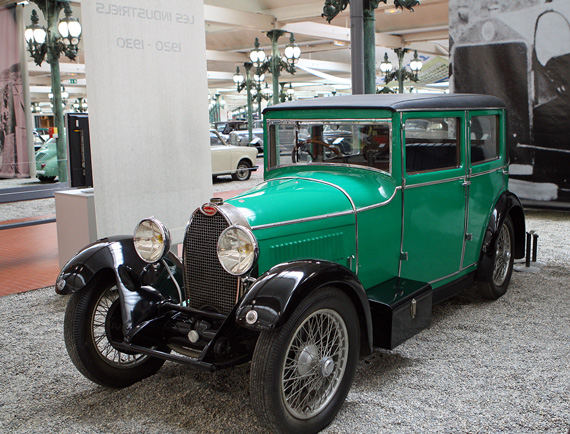

One of the last Bugatti designs of the 1920s. The Type 30 is powered by a 1991cc straight eight engine. The bodywork was made by the Bugatti Gangloff workshop.

This 1927 Bugatti Type 38 carries unusual bodywork. Its American owner M. Shaw had the car re- bodied to his own design. The chassis has been noticeably shortened.

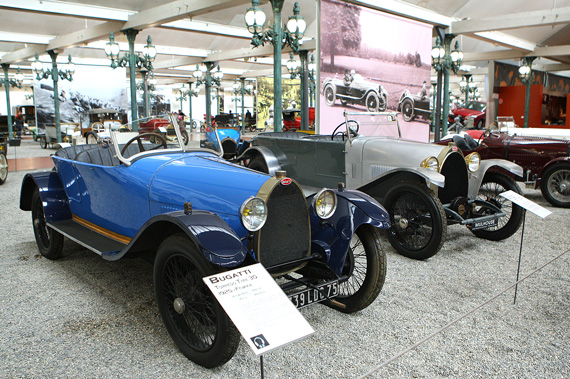

Fitted with a 45CV 4 cylinder 1496cm Type 37 engine this Type 40 Berline dates from 1928. The Type 40 provided very popular. Bugatti constructed a total of 790 examples.

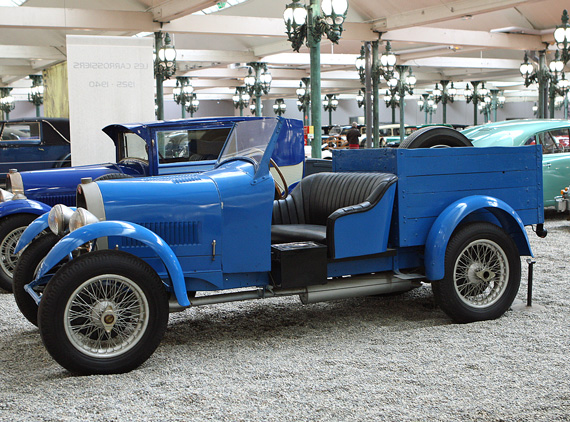

Ideal for taking your garden rubbish to the tip, this Bugatti pick-up (Camionette) actually crossed the Sahara desert in the hands of Lieutenant Frederic Loiseau of the French Army. The expedition, made up of 5 Bugatti Type 40s, set off from the Place De La Concorde in Paris on the 29th January 1929. In 32 days they covered 15000 kms of Saharan terrain at an average speed of 80 kph. This is the only known survivor of the expedition.

This is King Leopold of Belgium’s 1929 Bugatti Type 43 Grand Sport. Powered by a 2261cm 125CV straight eight engine with a top speed of about 180 kph.

The Type 44 proved to be a good seller, small in size but with reasonable passenger space. A 2992cm straight eight with 80 CV probably helped. This example dates from 1927.

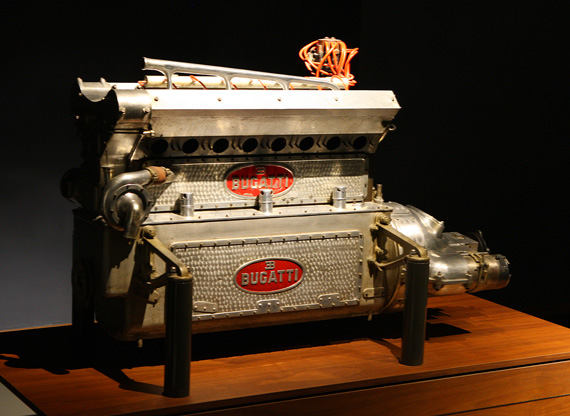

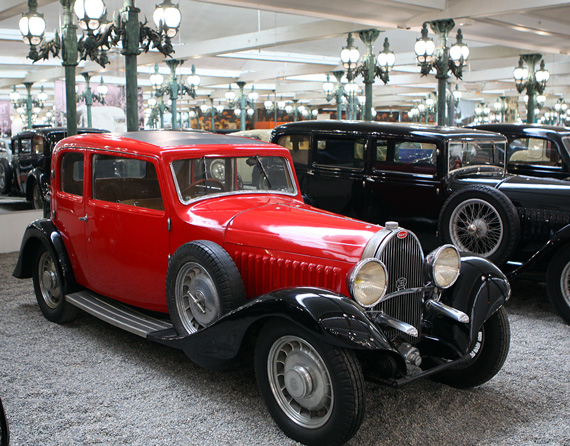

This big and very powerful (200cv) Type 50T was at one time owned by Pierre Michelin. I am led to believe that the coachwork is by Million Guiet.

As noted in the book review, the T50 was a cast iron block, whatever your eyes tell you.

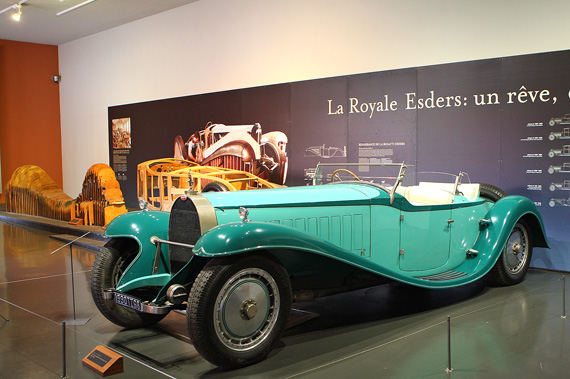

This is a recreation of the Esders T41 Bugatti began by the Schlumpfs and finished in the 1990s. It was said that the original body disappeared after removal by coachbuilder Binder.

The last of the French Bugattis. You enter the museum via an elevated walkway. As I looked over the side of the walkway this is the sight that greeted me, a Bugatti Type 57S. A taste of things to come.

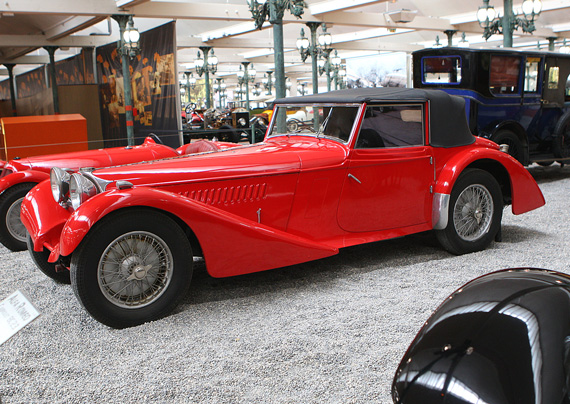

Another Type 57, this time with cabriolet coachwork dating from 1936. In 1934 the factory reduced their product range to just one model, the Type 57.

This Type 57SC however has bodywork by Ghia. Originally constructed in 1939 the chassis was re-clothed by Ghia in 1951.

There are a ton of Bugattis in the museum and a lot of them are Type 57s. This example from 1938 has bodywork by the British subsidiary of the Belgium coachbuilder Vanden Plas.

This unique Type 64 was the last model to be designed by Jean Bugatti in 1939. Unfortunately a lack of funds and the outbreak of World War Two laid waste to any plans to manufacture it.

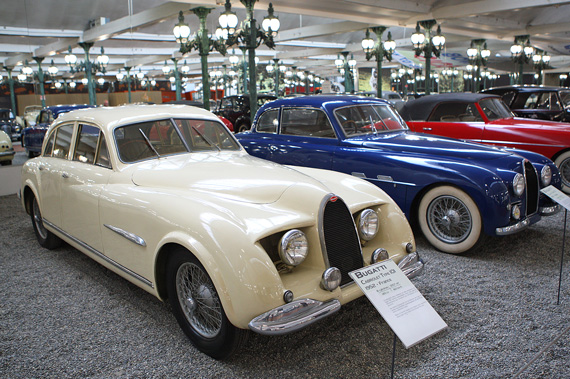

After World War Two following the death of Ettore and his son Jean, in order to try and restart production the Type 101 was developed from the previous Type 57. Six production models were built. Two further T57s where converted to T101 spec. The last T101 was built in 1965 by Ghia to a design by Virgil Exner in an attempt to revive the marque but finance was not forthcoming. This rather handsome example has coachwork by Gangloff. This example from 1951 was built on a converted T57 chassis and was exhibited at the Paris Salon.

The maroon Bugatti by M . Shaw was built in the Chicago area about 1959. The rear body is from a Model T Ford roadster. I have some of the build photos I got from a college classmate in 1960.

The beige Type 101 pictured above was in fact the prototype car built at Molsheim in 1950. It was designed by french stylist Louis L. Lepoix, who is best unknown today for his design of the standard Bic pocket lighter. Work on the car was apparently rather difficult to handle for an enthusiastic young man. In September, 1950, he wrote on a postcard to his mother: “I am working four days a week at Bugatti in Molsheim. Those imbeciles are insanely behind on everything, while I am working hard to get the car done.”

The display halls are illuminated by 900 cast iron street lamps copied from the Alexandre the THIRD Bridge in Paris, not Alexandre the 4th !