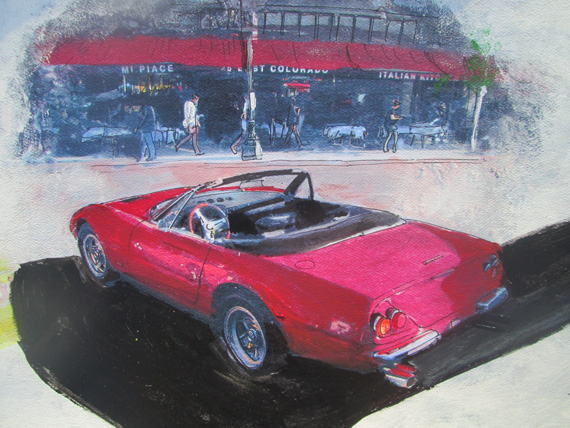

There are a lot of problems with this shot– crooked background, shadows from booth to right, but it conveys the ambiance of the event with European style outdoor cafes. I did the artwork for this article based on this photo.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Wallace Wyss is both a photojournalist and a fine artist. Here he explains how to use light to create “art” with photographs.]

Story and photos by Wallace Wyss

As longtime VT readers might know, I wear a few different hats. At a car show I am a reporter, i.e. photojournalist, taking the pictures to go with my report for Internet sites, magazines or for my Incredible Barn Finds series of books.

At the same time I see the show through the eyes of a fine artist and, if the light is right, try to attempt to portray the cars in my photos in a certain light and background that is not always identical to the pictures taken while wearing my photojournalist hat and “shooting for the record.”

And I’m here to tell ya that those two roles don’t necessarily mesh–often they fight each other tooth and nail…

For example, when I went to the Ferrari Club of America Southwest Region concours on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena in April, my overall assignment was to select the most interesting cars and shoot them for a straight story.

This shot of a SWB 250GT SEFAC had a lot going for it–racing stripe, racing history, bricks on street, nice long dark shadows, but the driver’s side had a little too much shadow for me to choose for a painting.

That’s because the media that receives my photo reports don’t care about art; they want “fully lit” pictures that show the whole car. So starting about 9 am I dutifully did just that, taking about 30 pictures as a photojournalist.

Painting with light

But before that, before the reporter’s hat was donned, so to speak, on first arrival at 7:30 am , I was wearing my artist’s hat, so I could ”paint with light,” a phrase I got from Ansel Adams, (I knew him because he was an honorary judge at Pebble Beach). I interpret his catchphrase to mean, as the sun comes up, the light is rapidly changing as you watch, and, if you have pre-picked the targets and are ready to shoot, you can “paint” the contours of whatever you are shooting as the light gets stronger. In mid-winter I have seen the light go from dark to fully lit in a matter of five minutes so it’s prudent to pre-select just two or three cars you want to shoot “artfully” because you won’t have a chance to capture more before they are fully lit up.

I got to the white Daytona 5 minutes too late–the sun was already too high, washing out the form. The shadow painted the fenders and hood (hard to say if something that subtle will show in the print) but I didn’t like the shadows on the front section including headlight doors. White and black are two car colors that are hard to photograph and paint, white washes out form and black makes form disappear unless you’ve got good reflections.

The only trouble is, the light isn’t as strong in spring as it often is on a bright clear winter morning, but looking at my photos after the show I felt I succeeded, capturing the forms of two or three cars that would have been impossible to see any subtleties in once the sun was fully up; the most difficult of all being the icebox white Ferrari 365GTB/4 Daytona.

So if you want to try out Adam’s “paint with light” philosophy, I heartily recommend arriving at your next car event at dawn, or even about 10 minutes before sunrise. Of course there may be a second chance, in that there is often a nice “golden light” at the end of the day if there are not many clouds. But the timing is all off because most concours are over by 3 pm and the cars are long gone by 7:30 pm.

An experiment in backlighting

Back in the 20th Century, when I used to shoot with film, I would never shoot into the sun, because with a set film speed, and seeing film has such a limited range, that doesn’t include coping with the intense light of the sun. But now shooting digitally, I have a fresh opportunity with an ever changing capability in my camera to try shots with the sun behind the car, my goal being to wash out the background but still keep color in the car. My goal was to keep some background for ambiance (to show the setting) but I still wanted to have enough background washed out so it couldn’t compete with the subject car.

The setting

Pasadena is a potentially good background setting for collector cars. The buildings in Old Town on Colorado Boulevard are old enough to be ornate in the style of the 19th century. Especially appreciated are the ornate filigrees on some buildings and there are the palm trees. The drawback was the usual placement of the cars—the majority parked cheek-by-jowl next to each other at a 45 degree angle with only a few selected ones chosen by the organizers to be displayed out in the center of the street, but those were too far away from the buildings to get nice architectural details immediately behind them.

The Boxer shot showed strong moxie—attitude, ‘y might say. But I wasn’t sure about the shadows on the upper part. A shot made 10 minutes earlier and from a foot higher might have defined it more for it to be selected for a portrait.

Of course once I pick up a paintbrush, as a painter, I have the choice of putting the car against any background I want, but the ideal if you’re capturing ambiance is to have the car against the same background you caught on film. That’s because the shadows will be different on the car and the background if you use a car from one picture and a background from another, the shadows won’t match, especially if the pictures are shot hours apart.

I also, in Pasadena, did a brief experiment to see if I could do a pen-and-ink impression of an event like those Continental travelers did in the 1700s before photography. I made four drawings, but failed. They weren’t lively enough to pursue so that exercise went nowhere.

With the California, I was a little too far back and thus lost the drama my slightly wide angle lens would have added had I been two feet closer. Shadows on driver’s side put me off…one problem with early morning shots is shadows from the car parked alongside.

Choosing a candidate for “art”

When I came home I put on my artist’s hat and looked over the pictures to see what I had. At least 40 were good coverage of the event but, to me, they were pedestrian, and had no dynamism whatsoever. They weren’t what I call “art.”

When it came to candidates for a painting, I finally narrowed it down to five:

-short wheelbase Ferrari front 3/4 LeMans car

-Daytona in white, front 3/4

-Daytona from the rear

-Boxer from the front

-California Spyder front 3/4

But then The Editor intervened. I told him I yearned to do a backlit shot where the background was “washed out,” and then ran a few photos by him including two backlit shots, but he expressed a preference for the rear 3/4 of the Daytona spyder, a shot which was not backlit. Well, you know about editors, they do what they do, God luv ’em.

But I still decided I would make a painting of the car he liked, but do the painting a little like a “backlit” shot by focusing in tight on that one car, giving it full color saturation and full detail, and then, as you move out to the edges, reducing color strength and detail in the surroundings until finally there’s a complete fade to white.

Why not just have an all-white background so the car is 100% the subject? If I went that route I’d be tossing away any opportunity to capture the ambiance of the event and whenever possible I like to show cars in the context of the event they were at, so you would know what it was like there. (My favorite of my own paintings is my portrait of a Talbot Lago at Pebble, where you see the crowd thick around the car).The open air restaurant in the background is important because the Pasadena merchants in Old Town have created a European-like setting, so one can pretend you are on the Champs-Élysées or Via Veneto. I admit I am guilty as charged of changing the awning to red to match the Ferrari (they call that “artist’s license,” similar to “poetic license”).

From Digital to Analog

The Painting. Almost done. Compare to lead photo above. Still trace of yellow car on left, restaurant could have used more people–another problem that comes with shooting early, an event can look like a ghost town, though it might have been packed later. I can’t tell if it’s “right” until I make the first print. Cropping from sides could change total impression.

Ironically there was one major change to the painting before I considered it finished (compare it to the photograph you see here). When I first completed it, I included a portion of a modern yellow Ferrari that was parked next to the Daytona but, when I stood back to view the finished painting, the yellow car was too distracting. I tried fading the color so it would be less so but finally painted it out and cropped the painting from the left so the focus is just on the Daytona (but you still see the yellow Ferrari reflected in the Daytona). The painting still might get more work before I run off prints. And then in making prints, there are considerations like paper weight and texture.

So next time you go to a car event, if you want to shoot for “art,” go early. Ansel would be proud of you….

THE AUTHOR: Wyss says a list of his prints from his paintings can be obtained by writing him at Photojournalistpro@gmail.com

A great tutorial on the art and science of Wallace Wyss. The talent comes from a proper integration of both, and from his vast experience. The best stories are told with the skillful use of both text and graphics as seen through the eyes of a master.

Very enlightening.

Wally, terrific article, good work! All the best. Paul