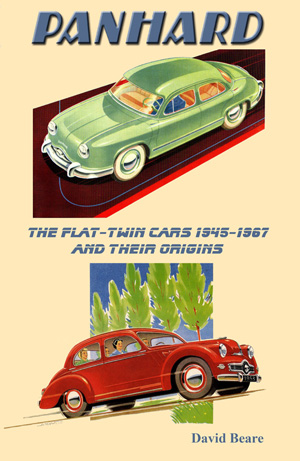

Panhard, the Flat Twin cars 1945-1967 and their origins

Panhard, the Flat Twin cars 1945-1967 and their origins

11.5 by 8.25

336 pages Softbound, approximately 1000 illustrations, B&W

$38.75 USD, £25 plus shipping

Order from https://stinkwheel.co.uk/shop/

Review by Pete Vack

This is one of the most important and well-researched books this year, in fact, in the past several years. For not only does it address a rare topic, but does so with immense authority based on superb research, a confidence that comes with deep understanding of the technical issues that are so much a part of the subject, a love of the marque that is both overwhelming and yet balanced and the ability to take relevant side roads that delightfully amplify the main subject. We are pleased that it is entirely in English.

The author, noted Panhard historian David Beare, gives us a brief historical look at the Panhard-Levassor firm from its beginning in 1891, enough to set the stage for the tiny and amazing post-war Panhards.

If ever there was a misunderstood and underrated car (at least outside of France), it was the Dyna Panhard. Even the name is confusing, often Panhard Dyna, and also seen as Dyna-Panhard with a hyphen. Born under the reign of Nazi Germany during WWII, the project was encouraged by Jean Panhard, the son of the founder, Paul Panhard, and two remarkable engineers, Loius Delagarde and Louis Bionier. (Remarkably, Jean Panhard reviewed the text of Beare’s book and last month appeared at a Panhard club celebration of his 100th birthday!)

Jean Panhard on his 100th birthday celebration on July 15th. Photo copyright DF/photoIMAG'ination; it was previously incorrectly credited, our apologies.

Prior to the war, Amilcar had built 681 aluminum chassis cars called the Compound, designed by Grégoire, but the war stopped further production. Prototype work continued during the war, and in conjunction with Aluminum Français, Grégoire developed four front-drive all aluminum small cars (weighing only 877lbs). They were then analyzed by all four major French car companies. Citroen would continue on with its own 2CV project, Peugeot with the 202-3, and Renault would steal the five star wheel idea to use on their 4CV. Only Panhard would embrace the concept, and then with caveats.

The AF-G as it was called, was very similar in scope to the Delagrade-Bionier project at Panhard. Grégoire signed a contract with Panhard for patent royalties and consultant fees in February 1944.

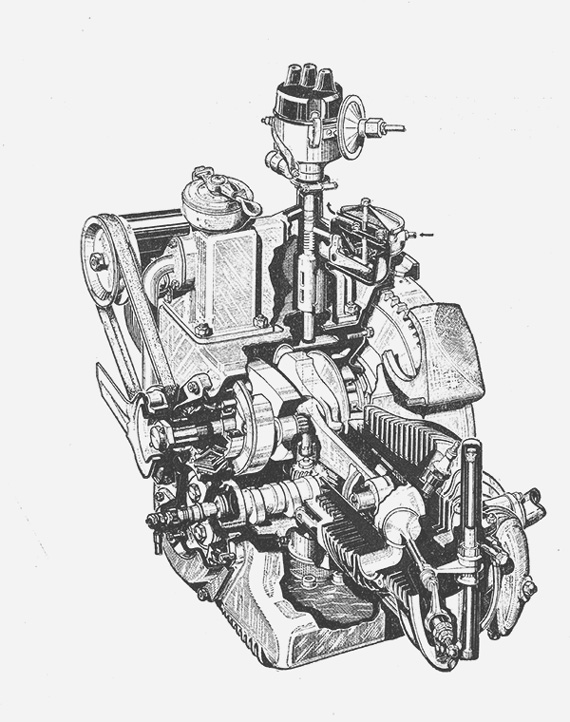

Both Delagarde and Grégoire had designed flat twin engines; the primary difference was the use of roller bearings for both the big ends and the crank bearing on the Delagarde design. Grégoire dismissed the roller bearings, but Delagarde won out; that decision would be allow the tiny engine to notch up a small displacement competition record at major events unequaled to this day. Delagarde also designed a small roller to fit between the large rollers in the cage; this tended to reduce wear by spreading the load more evenly. A Panhard engine could be revved to 7800 rpm and had exceptionally long life.

By their very design, Dyna Panhards were meant to race. Here are three Dyna X85s racing at Silverstone in 1951. Credit Autosport.

The AF-G had many lives, however, and thankfully Beare has the time and space to delve into the variants, which included the Kendall, the Hartnett, Fiat under Giacosa, and even Kaiser Frazer. Only the Hartnett in Australia was ever produced and only for a short period.

The Dyna Panhard X84 was first seen at the Paris Salon in 1946..a work in progress but production did get underway by 1947. It was one of the most advanced cars ever built. While it took many of Grégoire’s ideas to heart, the changes to his design were significant enough to deny him direct royalties. Court fights ensued, but in the end Panhard won out.

Nonetheless, the Dyna X84 and 85 models had a host of interesting features:

Chassis: stamped aluminum, spot welded with cast aluminum bulkhead/windscreen surrounds; floor plan and sills were steel.

Removable engine/running gear in unit, unique three torsion bar semi-independent rear suspension, transverse spring independent front suspension.

Body: all-aluminum in pressed sheets (a new process developed by Panhard suppliers).

Running gear: four speed transmission, fourth overdrive front wheel drive, rack and pinion steering.

Engine: 610 cc air-cooled four stroke opposed twin with roller bearing crank and rods, hemi-head design with torsion bar valve springs with 22 hp standard. Tuners would eventually pull as much as 80 hp out of an 850cc version of this remarkable twin.

That is some recipe for performance and provided the basis for many successful sports race cars, primarily under the banner of Deutsch Bonnet.

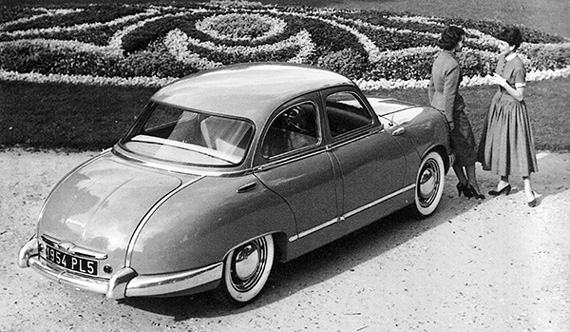

The Dyna X-84-85 lasted until 1953, followed by the more familiar (Dyna 54),this time in total aluminum, with an all-alloy body and platform chassis. The cost of aluminum vs. steel proved to be a major issue for Panhard and eventually the entire car was made of steel rather than aluminum. By 1955, the body shell on the Dyna was replaced with steel at a significant savings. Beare covers this fascinating technology in detail, describing the difficulties in creating a stamped aluminum body. Until Ferrari came along with the Ferrari 360, it was the only production car to feature an all-aluminum chassis.

Panhard topped the X85 by introducing the even more advanced Dyna 54. Everything was new aside from the drive train, but horsepower increased to 42 hp, or 50 hp per liter.

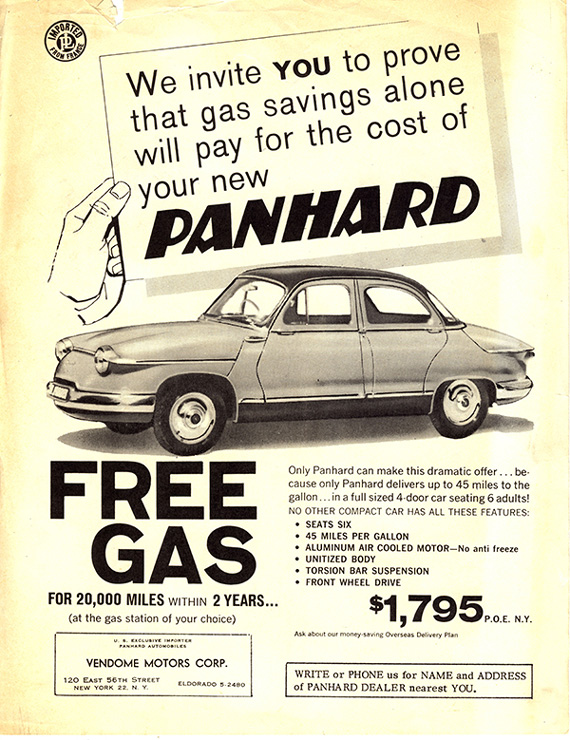

The 50 hp PL 17, was produced between 1960-1964 and the Dyna name was dropped. The last Panhards were the 24BT and CT series, beautiful new designs condemned by Citroen’s demand to use the 20 year old twin engine. Citroen closed the door on Panhard for good in 1967.

Panhards arrived in the U.S. in the mid-1950s in considerable numbers but never caught on. This is the PL-17 model.

The book covers all models in great detail, and along the way Beare tells us about design and manufacturing issues that really bring the history to life. The detail, research, and insights throughout the book are incredible; far too much to even begin to describe here. Suffice to say, that everything one might want to know about any post-war Panhard can probably be found in this book. We hope to have Mr. Beare present a few articles about the Dyna Panhard in future editions of VeloceToday.

The majority of the illustrations are sales brochures, but in this case, the effect works well. There are no restoration photos, no current images of Panhards. Yet there are 336 pages with about 3 images per page; that’s over 1000 historical images and brochures!

Well, we must find something to be critical of, mustn’t we? Far and above any nit picking, Beare’s book—and the subject itself — deserves to be a full color, glossy hardback. Perhaps there should have been two editions, the £25 softback and a deluxe edition. But this is basically a self published effort (although thoroughly professional!) and as Beare noted, “I also wanted to make the book affordable to enthusiasts. So many motoring books these days are, in my opinion, very overpriced and needn’t be.” Along these lines, we note that financial assistance was provided by the Michael Sedwick Memorial Trust. The Forward is written by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, who agrees with our contention that Beare’s book “deserves to be among the most significant motoring books of the year.”

Back to nitpicking, we noted a few minor errors, one being that Dante Giacosa did not design Ferrari F1 engines as the text indicates.

Captions are often lost in the text and inconsistent.

There is an index and a bibliography, but footnotes would have been a welcome addition.

But for only $38.75 (£25) plus shipping, this is truly a bargain and a must have for any French car lover or automotive historian, or for those who want to learn about one of the most technically interesting cars of the 20th century. The book is as fascinating as the cars themselves! Give it a 9 out 10 and highly recommend that you get a copy before the very limited run sells out.

I own a ’54 Dyna Z1 and am so proud of it! Excellent review! I am reading a borrowed copy of David Beare’s book. Must order one for myself. Tthanks for the review.

In the late 50’s a close family friend, Dr. Lou Costanza, an anesthesiologist in Jacksonville, FL wanted to get into SCCA racing and as a high school age sports car fanatic I was both egging him on and supplying whatever mechanical labor I could. His first purchase was a Dyna Panhard 4 door that we cut in half to make a two door coupe knowing that took him out of the sedan or road class or whatever it was then and into the sports category. The idea was that the resulting car with the engine tweaked a little would be so light that it had a chance in the 750cc or 1000cc class ( I don’t remember the specifics). At least six people including me worked on this crazy project and no one had any experience whatsoever. As I remember the two halves were not even welded together but riveted with aluminum strips. Needless to say we had a tough time getting by inspection. Lou, however, grew up in Elizabeth, NJ and just kept pressing until everybody threw up their hands and let him race. He managed to get his license with the car but after a race at Daytona the SCCA guys said no more. The car was dead last every race although Lou had his moments passing a few people. My last recollection is riding on a toolbox where the front passenger had been, touring through the pits at Daytona trying to settle below the window so no one could see me. Maybe somebody has photos of SCCA Florida racing in the 1958-60 period with an unidentifiable car. I will be happy to authenticate. After the Daytona race the car was scraped and Lou moved on to a Devlin bodied VW/Porsche special built by Karl Hloch of Al Sager Motors in Jacksonville. The 4 cam Porsche was long gone so we put a 3 cylinder Saab in for the 750cc class and that was real racing compared to the Panhard.

Et al,

Interesting comments…but cutting up a Dyna Z to make a “racer” humm not good, as one must know the Panhard were very successful in Europe and of course the Deutsch Bonnet (DB) a Panhard engined fiber glass was always the winner in it’s class in Europe..(Le Mans) and sometimes winner overall. I am the owner of a Deutsch Bonnet and one Panhard 24BT…having owned several DB’s. Actually in my garage at this moment a completely ready to “Drop” in…a Panhard 850cc engine. I had it shipped in from France with my SALMSON 2300s

Vive la France et Les Panhards

Panhard assembly

In Ireland. 1960-1963.

The building on the right at the far end of the yard was where I assembled the bodies on a trolley which locked under two Jigs which were made by McEntagarts (The Standard Triumph agents). the jigs were for the front and rear screen apertures and once these were aligned properly, everything else fitted ok. The jigs were made and mounted on hangers from beams (RSJ’s), using John Caldwells Dyna as a template.

The floor panel came complete with the heavy side runners in place so that ensured that the side panels were in the correct positions.

The spot welders that we had acquired from the original Standard Triumph assembly plant at Percy Place were old and hard to handle. As a result I burned quite a few holes in the roof panels where they met the drip rails and I had to camouflage these with solder. that is also why I filled those seams between the bonnet and the front door.

I also spray painted twenty three of the bodies there. The other five were painted by Reg Armstrong Motors at Ringsend (2) at Standard /Triumph on Cashel Rd. (3).

That building had a “Mill race” running at the west end of it and there were the remains of mountings for mill wheel.

The building facing the Lucan road entrance was used to store the panels and parts, while the tin shed building on the right was where I assembled the engine/gearbox assembly and built this on the heavy cross-member together with the two springs and front axle units. (The springs were made by “Springs Ltd.”of Wexford).

Also in that shed Paddy Duggan and Aiden Buggle fitted the trim and the wiring and windows etc. and then we all fitted (“Horsed”) the axles into place, Paddy bled the brakes etc. before I road tested the finished car.

A retired man called Tom McGrath cleaned all the body panels in a large trough of trichlorethylene which we kept in the yard for this purpose.

When Pierre Klauss came from Panhard, France, He took a lot of photographs of each assembly stage and said that he was going to show these to the Americans who were failing to successfully assemble their PL17’s and he said he would have pleasure showing them that “They were being built in a Farmyard” in Ireland.

I think that Ted Bemand (Panhard Club U.K.) tried to find those photo’s but to no avail.

Frank Curran.