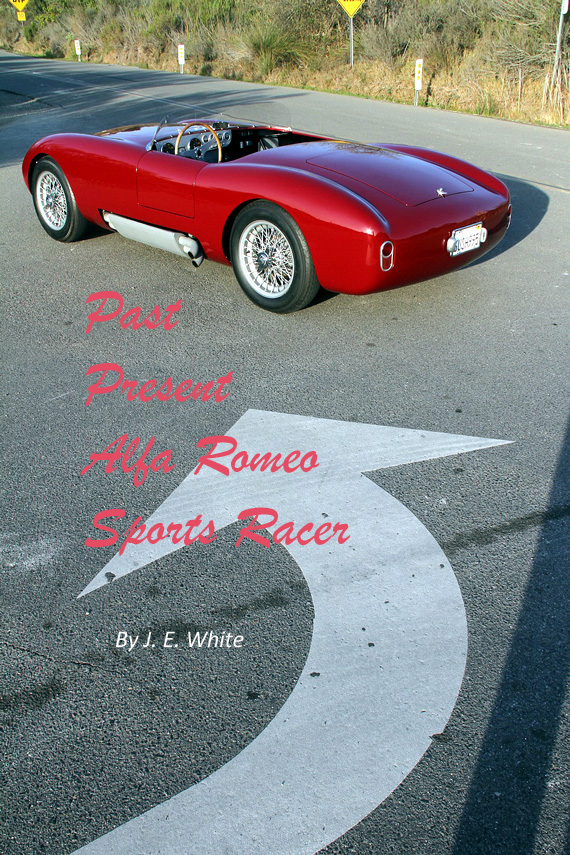

Creating a a stunning 50s-era Sports Racer from a derelict Alfa 2600

Alex Bacon grew up a student of automobile design. He cut his teeth as a teenager with a ground up restoration on his father’s ’63 Ferrari 250 GTE and fell willing victim to the allure of its sexy design, exotic engineering, and the quixotic addiction that comes from driving something you meticulously rebuilt piece by piece. He liked the car but he wanted less; less concession to creature comfort, less performance-robbing accessories, less overhead to wrangle through curves. An idea began to form, an idea about something light, fast and nimble, something simple but exotic: A purpose-built vehicle like the cars competing in the 1953 to 1961 Worlds Sports Car Championship. But first he had a skill set to acquire, experience to gain, time to refine a vision of just what that idea entailed.

Bacon spent many years restoring sports cars. The Bosley MK I that came out of his shop debuted at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 1996, garnering a First in Class and the Briggs Cunningham Trophy – the first of 5 awards to date that cars from his shop have received). He learned to fabricate everything from bumpers to aluminum trim to sliding, Plexiglas side windows, and to maintain client’s cars that included Siatas, Fiat 8Vs, Alfa Romeos, Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Maseratis.

Alex had long admired Ferrari and Maserati, but a V-12 Ferrari engine was rare and the price point was formidable, not to mention that separating one from its parent car seemed a historical violation. He considered the Maserati 6-cylinder engine, but it was too heavy (the crankshaft alone is almost 100 lbs.), equally rare, and almost as expensive, so the relatively plentiful yet exotic Alfa Romeo 2600 engine was a suitable choice. In keeping with the engine selection, the Sports racer should be Alfa Romeo in concept. Alex liked the Carrozzeria Colli-designed 6C3000M, but had reservations about building a replica; his SZ replica in progress at the rear of his shop was an ongoing project that demonstrated the difficulty in accurately reproducing any model. A car that incorporated his ideas was the goal. After spending 30-plus years restoring Siatas, Fiat 8Vs, Alfa Romeos, Ferraris, Lamborghinis and Maseratis, it seemed that designing and building his own car was just an extension of what he’d been doing all along.

The heartbreak of his chosen career, the heartbreak of anyone in the vintage automobile restoration business, is that after pouring thousands of hours into a project, a restorer’s final experience culminates watching the car disappear into a delivery trailer. Alex wanted a car that, after all those hours, he could own himself. He wanted the challenge of manifesting a personal interpretation of the 50’s Sports racers, and the only way forward was to build one. After restoring and driving a Maserati A6GCS, he knew how the car should drive. He had an idea of what it should look like as well. In many ways, that Maserati served as inspiration. But he didn’t want a racecar; his dream was to drive his car in rally, to and from shows, or any time or place he chose. He knew that he wanted an open car, and he trusted that his design instinct would deliver an aesthetically pleasing integration of line and proportion. What he needed was some way to begin.

In 2006, fate intervened with the opportunity to turn his idea into reality. Bacon found an Alfa 2600 beyond the pale of restoration. He then embarked on the design and construction of his sports racer. Not a 21st century reproduction or brutish knock-off featuring modern-day power train with electronic engine management, low profile tires and anti-lock brakes, but a car rooted in the past and constructed in the present as if time had stood still and the drive train, wheels and brake choices available in the mid-1950s were the choices you had now. Bacon’s project car would be coach-built in the era-appropriate superleggera method, the frame fashioned from steel, the aluminum body gas-welded together piece by piece. But it takes more than three decades of automobile experience to coach-build a car. It takes a vision, a very specific design aesthetic, and the broad knowledge of all that has come before. And that’s just the design. The rest takes 4000 hours and almost four years of singular focus. What you have when finished could be argued as the truest historical representation of a car that might have been. What you have is an Alfa Romeo Sports Racer.

The Chassis

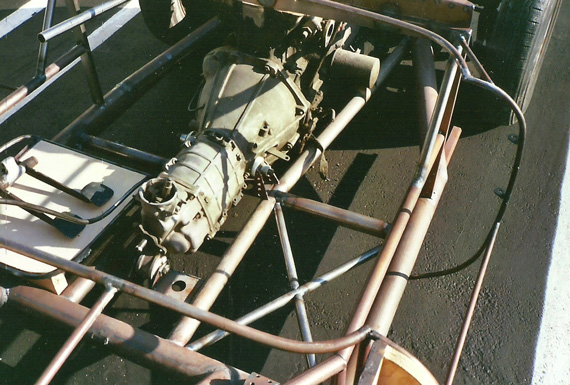

The fateful day arrived when the gutted, rusted-out Alfa Romeo 2600 chassis complete with engine and transmission was off-loaded at his shop. Here was a drivetrain as well as front cross member, rear axle, steering box, and oil cooler.

All the period-correct running gear was present but what was needed was a suitable chassis. Which type of chassis was the question. The purpose of a racing and sports car chassis has been best described as a method of locating all the various mounting brackets for a car by means of a complete structure. The goal of that complete structure is stiffness and torsional rigidity, meaning no flexing, twisting or bending, and made as light as possible. Solutions as complicated as the famous multi-tube “Birdcage” Maserati Type 61 chassis, and the elaborate space-frame Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR chassis are well-known success stories. The 1958 Lister-Jaguar achieved those goals using a ladder type chassis design. For Alex Bacon’s sports racer, given that the original front cross member and rear axle would be used, this type of chassis design seemed logical.

With that decision made, what followed was construction of a twin tube, ladder-type chassis of 3″ diameter round tube sections with diagonal bracing. The chassis was laid up on a granite bench to keep all pieces true and square, level and plumb. The 92″ wheelbase was based on the Alfa Romeo 6C3000CM and, since the stock Alfa Romeo 2600 front cross member and rear axle were used, track at front and rear match that of the donor car. The 6-cylinder engine and 5-speed gearbox sourced from the donor car were moved 19 inches rearward for ideal weight distribution. The engine and gearbox were lowered onto the frame and situated with wooden blocks so that 2″ diameter round tube sections could be fit longitudinally around the sump and laterally beneath the transmission. motor mount brackets were fabricated and the steering column mounted to ensure sufficient clearance at the exhaust manifold. An additional rear transmission mount was designed to provide rock steady attachment. Rubber, rather than solid motor and transmission mounts, was selected to dampen vibration pulses feeding through the chassis to the cockpit.

The firewall bulkhead was constructed and installed, and the position of the dashboard, door pillars, and pedal box determined. Additional 1.25″ round tube sections were fit and cross-braced beneath the seats and along each outboard side to enclose the cockpit. The rear bulkhead was located behind the seats and behind the rear bulkhead, and a lateral, perforated spar was welded between parallel, 3″ diameter round tube sections that angled upward from the lateral rear chassis tube section to the upper coil spring pads.

Outboard, 2″ diameter round tube sections from the twin tube chassis join at the upper spring pads, and longitudinal 1.25″ diameter round tube sections were installed adjacent the spring pads to absorb suspension loads and control chassis flex. Since a live rear axle was used, fore and aft location depended on the lower radius arms, and lateral axle location on the upper trunnion. The lower radius arms were equipped with Heim joints. The stock, rubber trunnion bushings were replaced with custom-machined urethane bushings. The original 2600 driveshaft was shortened and modified with a more robust U-joint to eliminate the problematic, flexible rubber coupling. With the planned engine tuning and increased horsepower, the inevitable failure of the flexible rubber coupling within close proximity to driver’s femur was considered an unacceptable risk.

Now that the complete drive train was in place, the original, bolt-on steel wheels were mounted and the chassis was mobile. Ride height calculations were made using wood block shims beneath the frame. The completed vehicle weight was estimated to be less than 1800 lbs., so appropriate rate coil springs front and rear were purchased.

Consideration for side-mount exhaust, fuel tank, battery, and radiator required more planning, and an aluminum radiator was purchased so that the supporting framework could be designed. A fuel tank was made up using hammered and riveted aluminum sections emulating period construction techniques; in a sensible nod to safety considerations, it conceals a safety fuel cell. Dual electric fuel pumps and canister fuel filter were mounted ahead of the fuel tank, just behind the driver’s seat, and accessed through one of two removable panels in the rear bulkhead. The battery was located behind the second removable panel on the passenger side. A muffler was fabricated from steel-expanded metal sheet rolled into tubes, surrounded with fiberglass, and sealed within a longitudinal, oval sheet metal enclosure. The muffler was positioned on the driver’s side rocker panel. Finally, the stock Alfa Romeo 2600 handbrake was fitted outboard of the driver’s seat rather than on the center console.

This will wrap up Part 1. Part 2 will begin with the creation of the body.