Story and photos by Paul Wilson

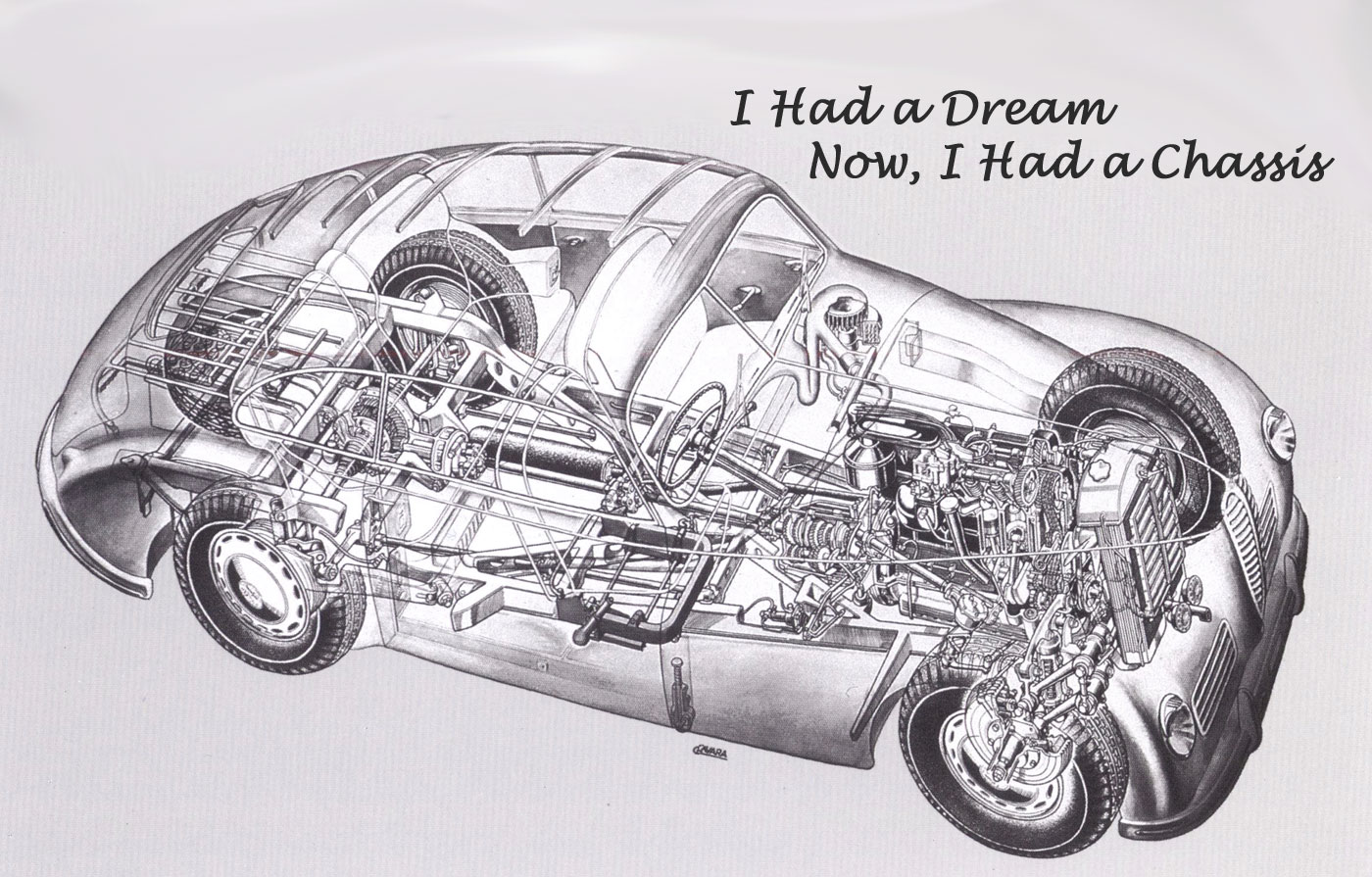

My dream of building a roadster body on an Alfa 6C2500 took a startling turn, from something absurdly impractical to an idea that might be possible. I was talking to a collector who was restoring a unique 6C for Pebble Beach, when he casually mentioned that he had a parts car.

It was the sedan version, called the Freccia d’Oro. It wouldn’t have been a parts car unless it was already in derelict condition, and he’d plucked from it various rare mechanical parts he needed for his other car. He thought he might put its body on a modern chassis. What would be left? Well, more or less what I needed most, a chassis. We made a deal.

Luckily both he and I understood what a parts car is. It’s the end of the line. It’s a pile of parts that has no future as a car. It’s just a backup source for that rare item you need unexpectedly, and can’t find anywhere. So when I went to fetch it, I was prepared for what I found. All the mechanical parts had been removed. Some were at the restoration shop, I picked up others at the owner’s farm. The internals of one front suspension unit were scattered on the floor of his barn, the guts were spilled out of a broken differential casting. His tenant farmer helped me load the parts into my truck. He asked me what I was going to do with them. I’m going to restore the car, I said. His reply: “Glad it’s you and not me.”

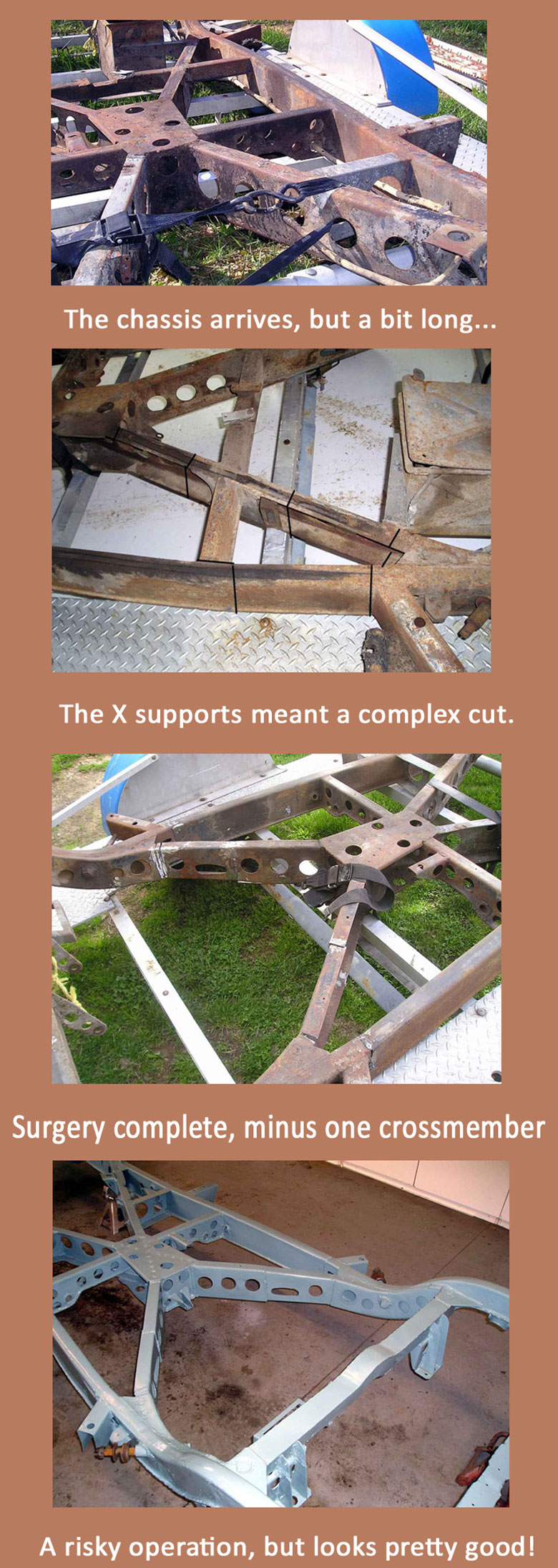

The Freccia d’Oro parts car sat on the 6C2500 long chassis (118″ wheelbase), but I wanted the short chassis (106″ wheelbase) of the sportier versions. They were identical except for another crossmember and longer chassis rails. The remedy was obvious (see above): I got out my Sawzall. The central X-brace also needed modification, but the result closely resembled the original short chassis. A pair of new short-chassis torsion bars came from California. They fit perfectly.

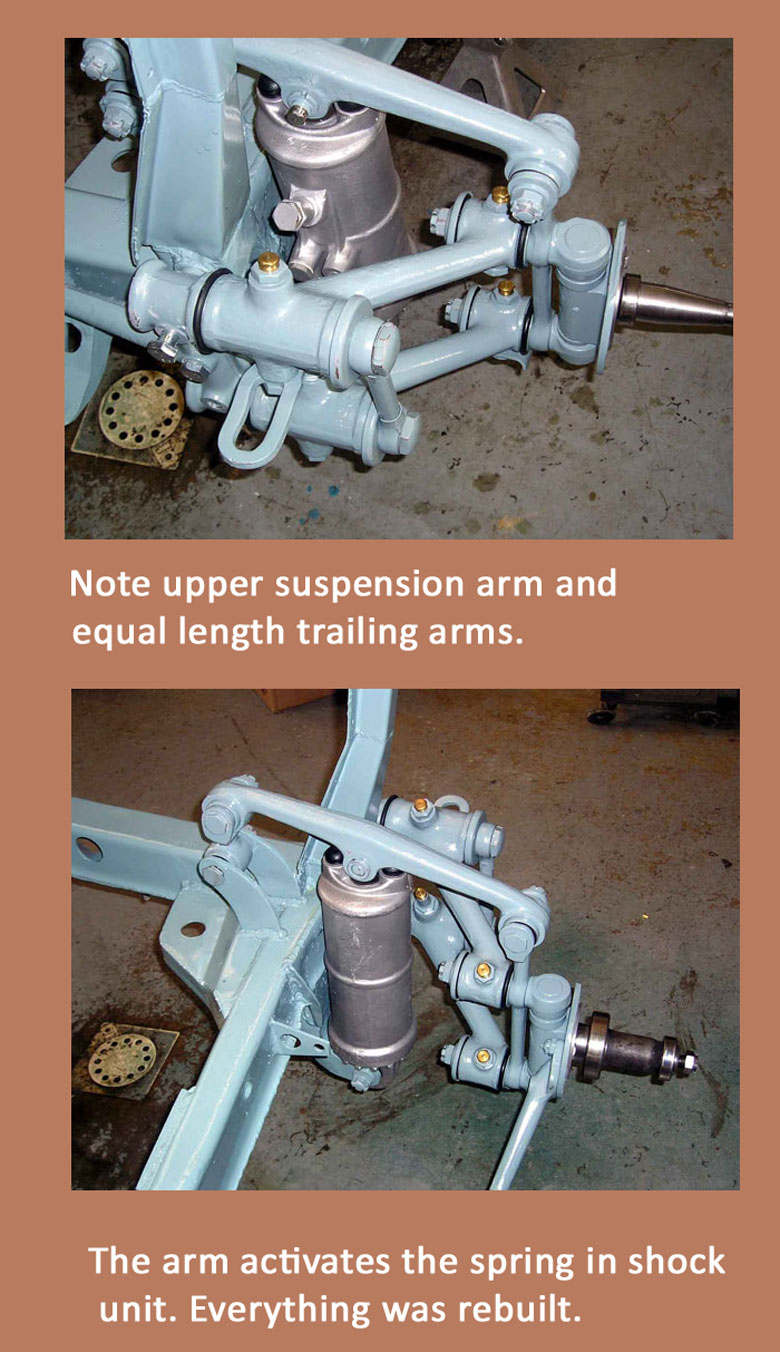

The front suspension was state-of-the-art for the late ‘30s. Like the Mercedes GP cars and the Alfa 2.9, it had parallel trailing arms. Early Porsches had these, so did the Aston DB2. Ferdinand Porsche even put them on the VW. They ensured a precise vertical movement relative to the chassis, unlike unequal A-arms that in a turn increased negative camber on the outside wheel and created horrible angles on the inside one. It took a while before engineers realized that the geometry of unequal A-arms helped the outside wheel stay vertical when the body rolled, giving it more grip, and because the inside wheel was unweighted, what it did didn’t matter much.

Trailing arms create a lot of stress at the hinge point, which the Alfa takes care of with two sets of needle bearings on the shaft. Complex, and expensive–but who cares? This wasn’t a car built to a price. The coil springs are housed in castings containing oil, which is pumped up and down with suspension movement, serving as shock absorbers. What do these internal parts look like, and how do they work? I had no clue. All I knew is that some of them were missing. Luckily, someone in Australia agreed to restore the complex, incomplete front suspension units in exchange for an engine and some other spare parts I had.

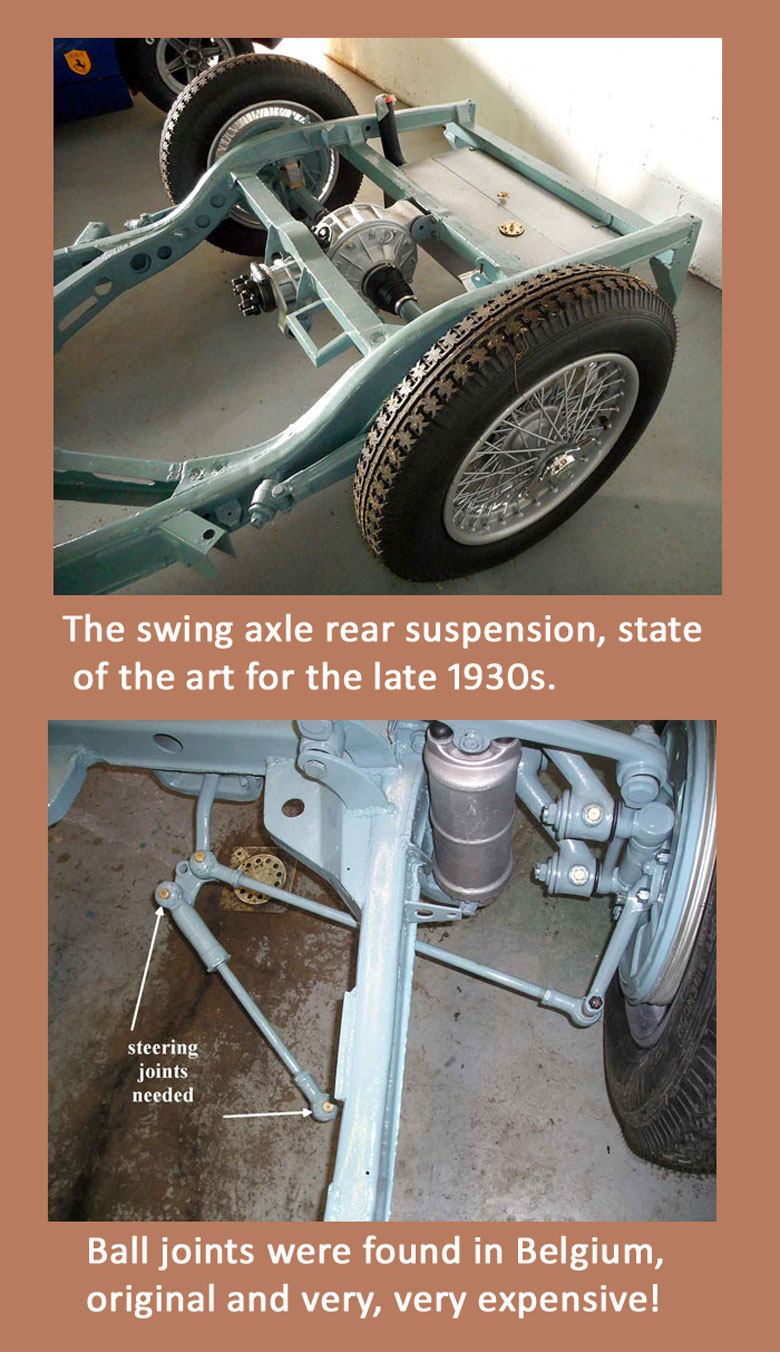

Finding parts for rare cars is unpredictable. Sometimes you get a break. My parts-car differential housing was broken, and the ring and pinion were dubious. But through the grapevine I found a whole rear end assembly, rebuilt, in California. (I) The owner suggested a fair price, a deal was done. Like the front suspension, this was state-of-the-art, high-tech, for the late ‘30s: independent, with swing axles and longitudinal torsion bars. Auto Union and Mercedes GP cars had by then abandoned swing axles for a de Dion setup, but Alfa won the Mille Miglia in ‘38 using them. How did they make them work so well? They did understand the need for a stiffer frame and softer spring rates with independent suspension. Tires with relatively low grip reduced the jacking effect that hurt the VW and early Corvairs so badly. And low unspring weight was an advantage on rough roads.

Then I needed two ball joints for a steering arm. (J) How hard could that be? One ball joint works just like another. With a little machine work, even something from NAPA could be made to fit. But the original parts are distinctive, assembled units. And my rules were strict: I was restoring a correct classic Alfa, not building a street rod. So a worldwide search began. A friend who has a company with Italian and U.S. branches bought several major classic Alfas from a dealer in Italy. If there were ball joints in Italy, he assured me, this guy could find them. I gave my friend a Freccia d’Oro grille he wanted, and he told the dealer to start looking. A year later, with some embarrassment, the friend reported that none could be found. Eventually a pair was discovered in Belgium. The owner, unfortunately, knew that they were the last ones on earth. They were expensive.

Talking with the parts car owner, I discovered something significant. He had used its engine for his Pebble Beach car, which I told him the judges wouldn’t like (they didn’t). Early 6C2500 engines had side plates on the block; later ones had aluminum plugs. His car should have the early engine. I had one; we should swap. He agreed. I then looked up the number of the spare engine I was giving him, and was startled to find that it started life in one of the 1940 team race cars. A toolroom copy of at least one of these exists; for its owner, having its numbers-matching original engine would be very desirable. But that would involve even more trades. The parts car was given to me on generously vague terms. If the balance now had tipped to my advantage, was it possible to put a dollar value on that? We decided it wasn’t. There was no further mention of payment.

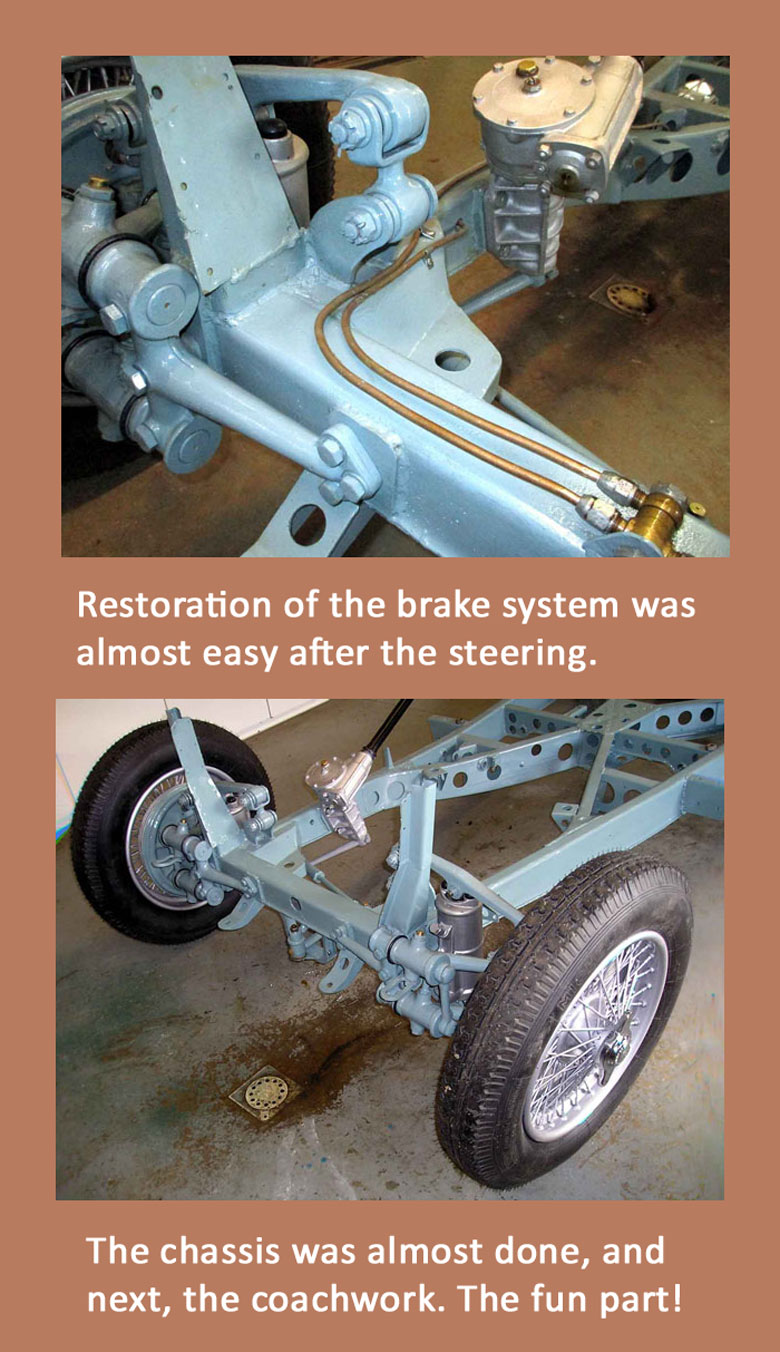

I renewed the brake shoes, refreshed the hydraulics, ran the brake lines, had the wheels restored, put on tires, and got a fuel tank and a radiator. The chassis was ready. It was finally time for what I dreamed about, making the body.

Paul

Incredible work on your part

George K.

Paul,

You are a miracle worker to bring your dream to fruition. What a beautiful creation you have put together. I’d love to see the finished product one of these days.

Regards,

Frank

When will the book come out?

Wonderful!

Chuck

Paul Wilson is very talented and a nice guy to deal with on Alfa matters. I am glad we could share our experiences building and restoring Alfa 6C2500 cars. Best of luck Paul with your current project. Fred.