Story by Paul Wilson

For my 6C roadster body, I made two important improvements in my technique. I used steel instead of aluminum. And with a few changes, I made my wire-form buck much better.

The Lotus and the Amilcar were originally made with aluminum bodies, so I had no choice of material. Aluminum is light and easily worked. So why would anyone use steel? Experience suggested some answers. First, it’s hard to get good welds in aluminum without much better (more expensive) equipment than I have. More skill, too, maybe. But I still don’t have it after twenty years of effort and instruction from many experts (none of whom could do fast, tidy welds with my welder). If practice would do the trick, I’d have it by now.

Aluminum has other disadvantages. It’s hard to attach to the inner structure. By the ‘30s, the Italians no longer used wood body frames. Touring’s famous Superleggera system wrapped aluminum around a light truss made of steel tubing; other systems were simpler. But they all used steel, and you can’t weld aluminum to steel. And unless they are tightly connected, the aluminum adds no strength. It’s just clothing for what’s inside. Welded-together sheet metal sections, as car designers gradually realized, are so stiff and strong that they can even replace the traditional chassis. Hence the unit body. So welding the skin to the inner parts seems like a good idea. How about weight? If the skin adds no strength, a heavier structure is needed for equivalent stiffness. And how heavy is steel, anyway? I compared a steel door skin with an aluminum one: one pound difference. No big deal.

Forming shapes in steel, though, I thought would be difficult. However, I had no choice when making front end parts for my coupe, which had to be welded to steel fenders I took from a ‘47 Buick. So I started experimenting. 18-gauge steel was too thick and heavy, 22-gauge too flimsy, but I found that 20-gauge (.0359″) could be shaped without much trouble.

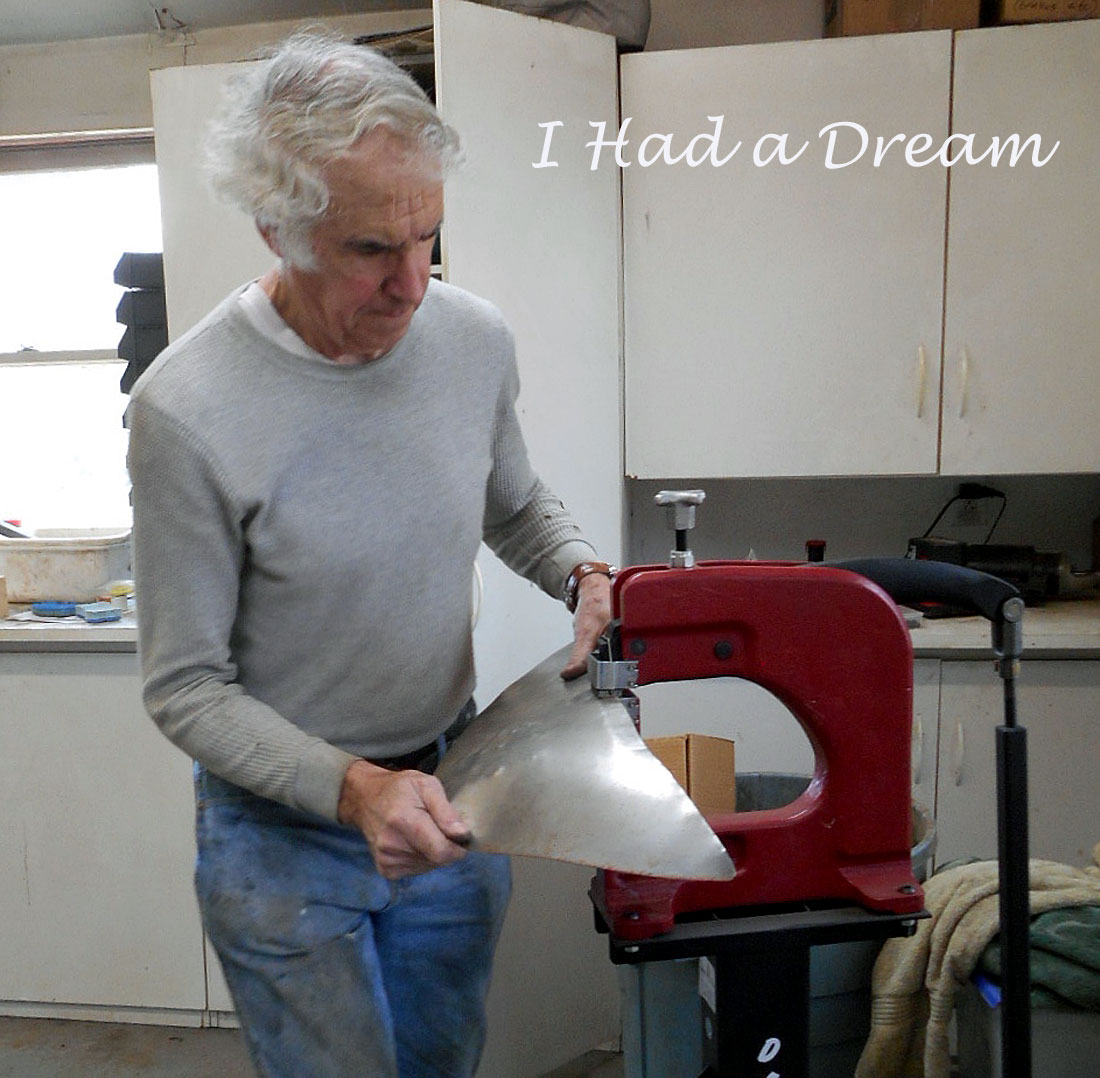

By then I’d bought a foot-operated shrinker, which has a deep throat so metal can be gathered in from the sides of a panel. It worked very well, better than stretching with a hammer and sandbag (it’s hard to roll out dents in steel). Soon I could make what I wanted as easily in steel as in aluminum.

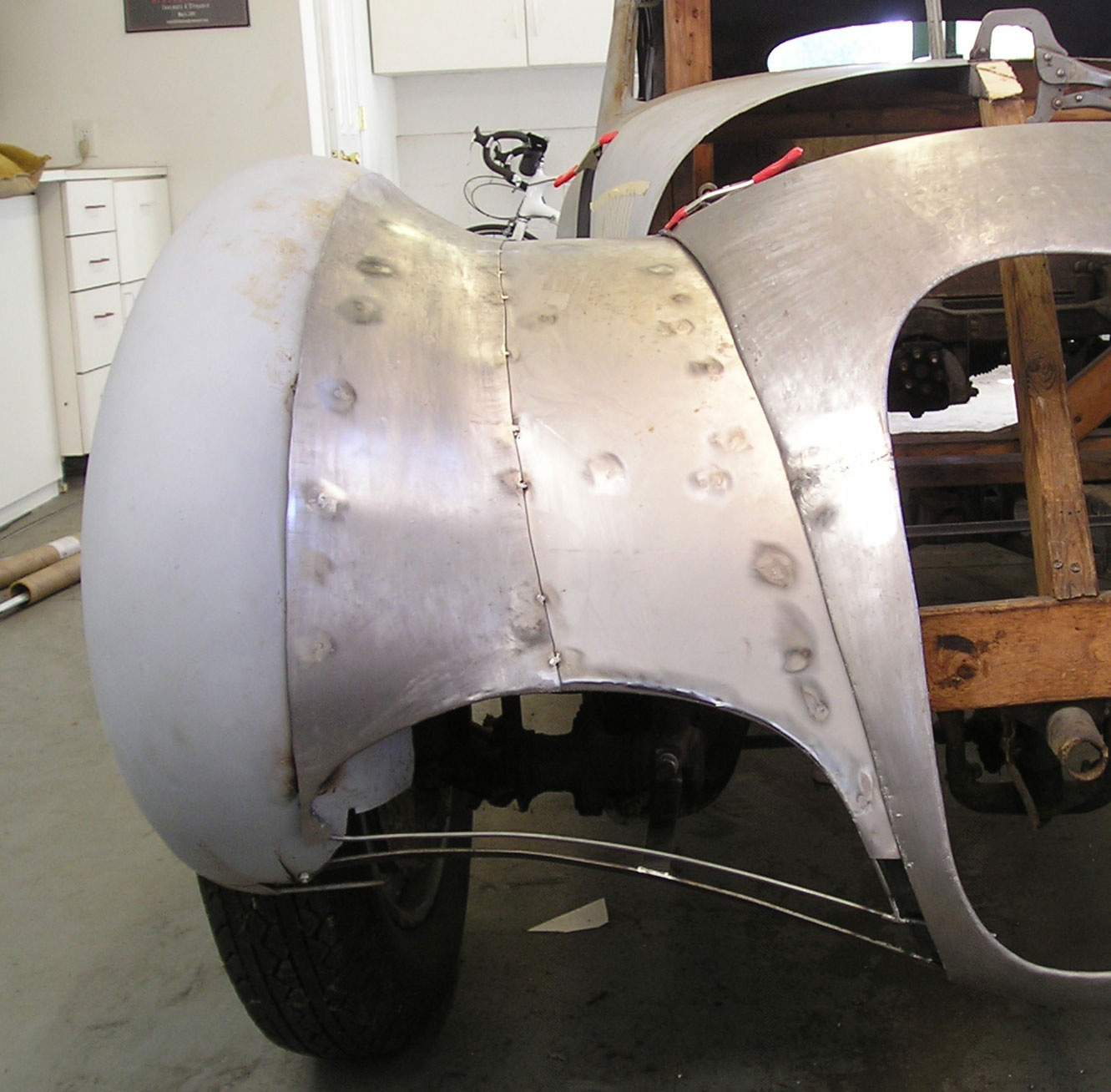

A buck made of steel rods had worked well for my Lotus tail. It was easy and quick to make, and easily modified. Using thicker rods–1/4″, not 3/16″–took care of the flexing problem. Using a wood frame clamped to the chassis, I fixed the steel-rod form of the outer fender rigidly in position. Then I started the metalwork. Simple convex panels are easier to make than the subtler inner fender contours, so the work went quickly. Soon I got an exciting preview of what the design would look like.

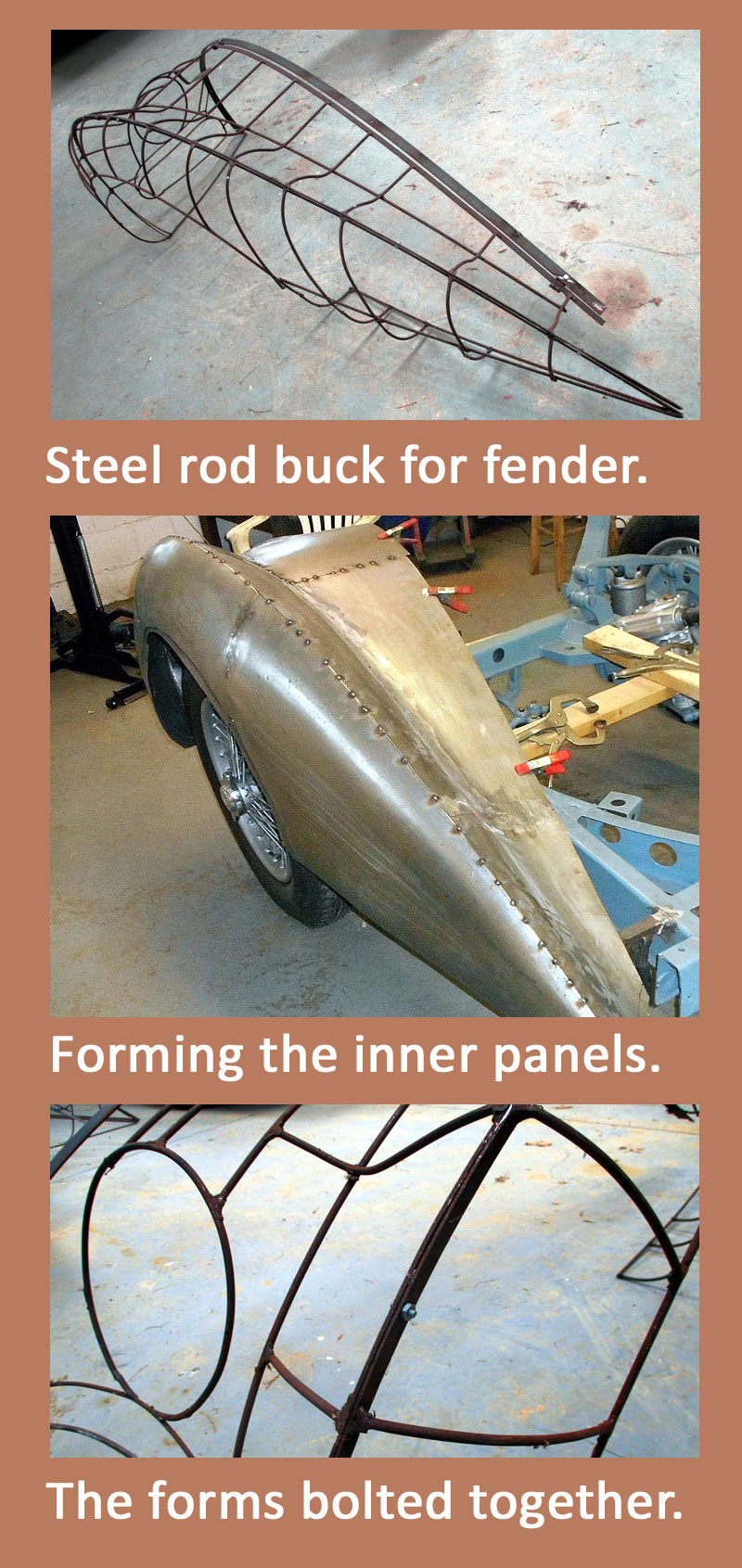

I then made a steel-rod buck for the whole front fender, and formed the inner panels. Making the buck in sections, with the outer fender form bolting to the inner at the profile strip, not only reduced the components to manageable size, but with flat stock (1/8″ x 3/4″) defining the profiles, mirror-image matching of right and left sides could be made easily and accurately. I could bolt together two profiles, then weld rods with exactly the same curve to each side.

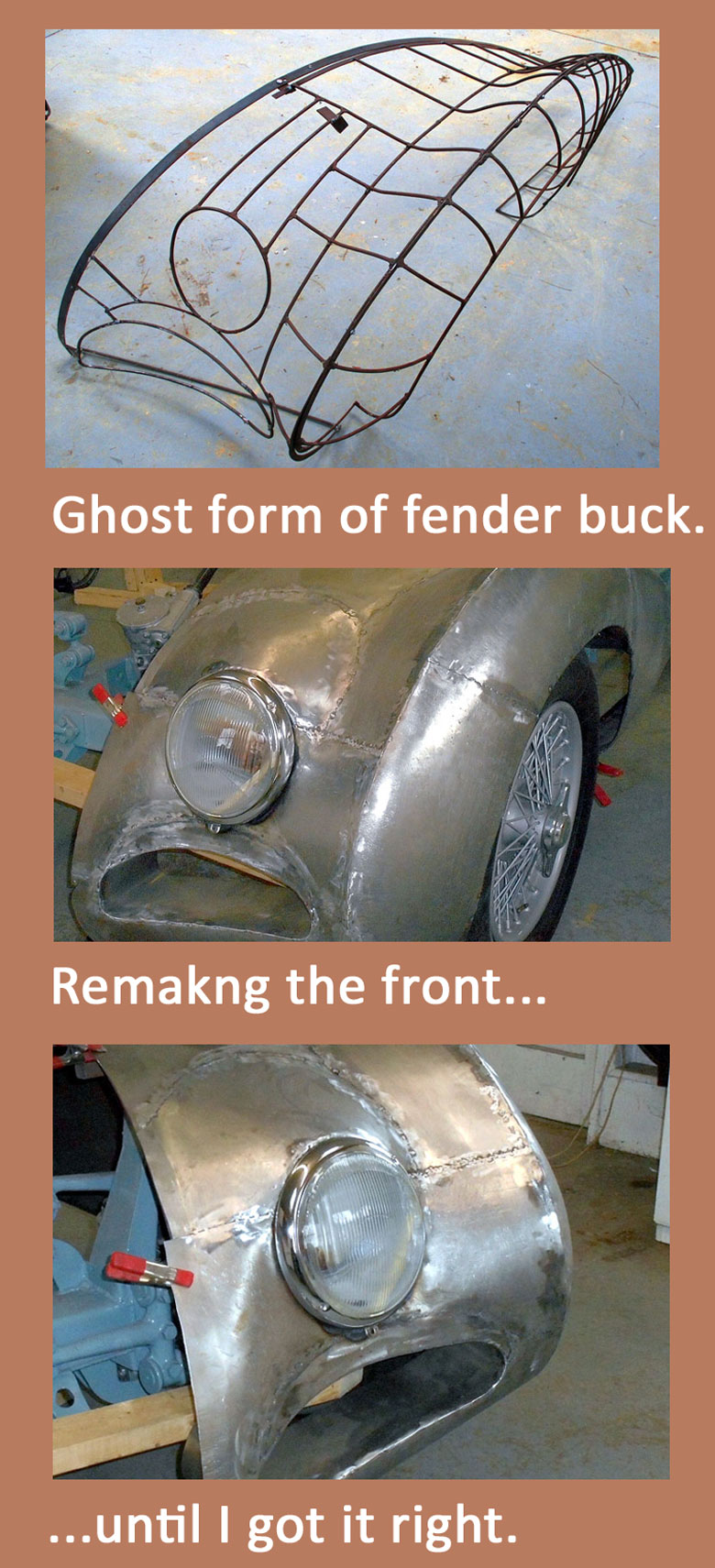

Getting the front end looking the way I wanted was a challenge. It looked OK in the ghost form of the buck, but when I added the sheet metal and mounted it on the car I wasn’t happy. I don’t know how the Italian fabricators got it right the first time, working from some drawings given them by the designers. But here my system showed its advantages. I could imagine what I wanted, try it out, and then do it over if it didn’t look the way I expected. Doing everything myself has obvious limitations, but communication isn’t one of them. First I made the grille too upright, then I overdid its slope and aggressive “chin,” then I settled on a compromise. With each change, I just had to cut and bend a few rods, and remake the sheet metal for that area. Evidence of these second thoughts is visible under the headlight area.

Having worked out this system with much effort and many time-consuming missteps,

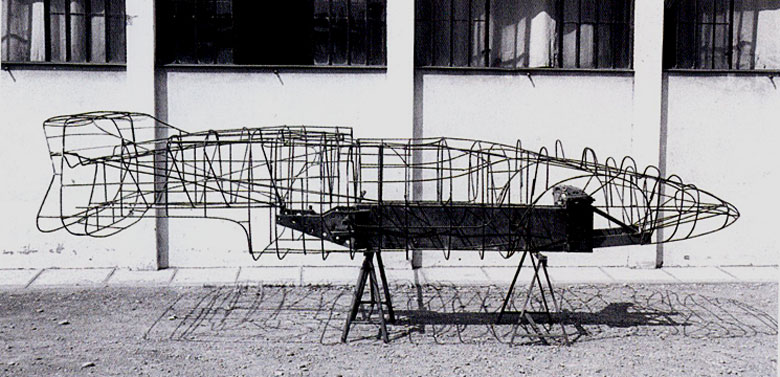

I made a discovery: it had already been invented, by the Italians, seventy-five years ago! I found pictures of an Alfa 2.9 under construction with fender shapes defined by steel rods. Another shows the shape of the Peter Brock De Tomaso P70. With similar methods, it’s clear that their standard of accuracy could not have been much different from mine.

Peter Brock described the Fantuzzi method of a creating a wire form buck for his De Tomaso P70 in his book, “Road To Modena”. Photo courtesy Peter Brock.

Lots of challenges lay ahead, but the body construction was off to a good start.