Story by Peter Darnall

Black and White photos courtesy Peter Brock

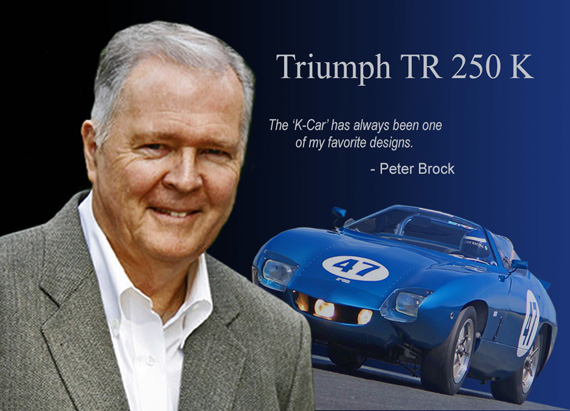

The K-car has always been one of my favorite designs – Peter Brock

High praise indeed! Peter Brock can include the Corvette Stingray, the Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe, and the Hino Samurai in the portfolio of exciting cars he has been involved with. I first saw the Triumph TR-250K in person at the David Love Memorial event at Sonoma earlier this year. The sophisticated wedge-shaped profile of the car was simply elegant. The K-Car, on its looks alone, might have saved Triumph from oblivion, but it was never put into production.

And therein lies a tale…

Enter Kastner

In the mid-1960s, W.R. “Kas” Kastner was the Director of Motorsports (US) for British Leyland. His office was in Southern California. He was concerned with the lackluster sales of Triumph sports cars and often discussed the situation with his friend and neighbor, Peter Brock. Brock was running the West Coast factory backed Datsun team (BRE) with the 240Z. Kastner was doing the same with Triumphs. The ‘Car Wars’ had heated up by 1967; C-Production racing in the United States had become a battleground. Porsche factory-backed 914-6s and 911s, fielded by Al Holbert and Richie Ginther, and Carroll Shelby’s Toyota 2000 coupes were formidable competitors. Corporate interests recognized racing success translated into sales . . . sports car racing had become a winner-take-all donnybrook.

Both Brock and Kastner recognized that spirited competition between Datsun and Triumph could keep both groups in the racing game. Triumph, if it were to compete at this level, however, would need considerable upgrading. In late 1967, they decided to create a prototype based on the existing Triumph IRS TR-4 chassis, Brock would design an aerodynamically efficient body with the goal of improving both performance and esthetics. The goal was to have their car ready to compete in the upcoming Sebring 12-Hour Endurance Race. Both time and money would be in short supply.

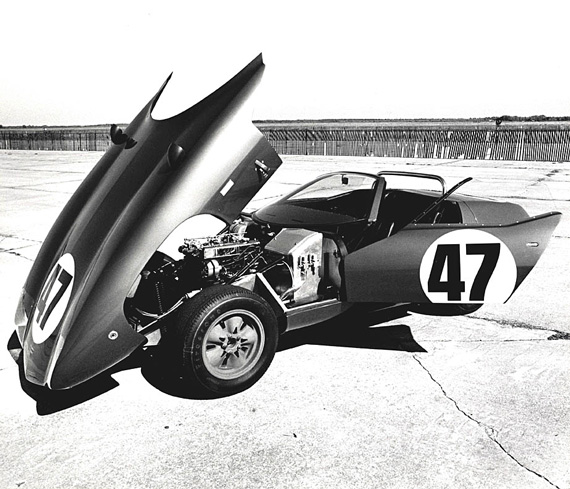

Ready to race! TR250K Sebring 1968. Peter Brock’s aero-bodied TR still looks like a modern production sports car with full wraparound windscreen and faired-in headlights.

Kas Kastner approached Triumph management in England with the idea. He had a sketch of the car drawn by Brock and an agreement from Editor Leon Mandel of Car and Driver magazine to feature the car on the cover if it competed at Sebring. Kastner’s mission met a tepid response, but Triumph did agree to commit $25,000 (USD) to the project. Brock speculated:

Having Kas show up and try to explain what was needed in the United States was probably not to their liking or even understanding. The people in their ‘States’ office “got it” but the Brits were clueless. I’m sure my hurried sketch didn’t resonate with anything in their rather conservative world so they pretty much passed on the idea. Not being “car guys” they couldn’t understand the aero concept . . . Their engineers were probably well into a new design which would eventually become the TR-7, but with a rather staid Michelotti exterior.

.

Brock’s partially finished quarter-scale model of the TR250K in clay. Note that the original coupe body has been cut away to create an open cockpit sports-racer. Time and finances dictated the decision to build the roadster version.

The money put up by Triumph was only a fraction of what the real cost was likely to be. The challenge to create a sports car which could compete on the track with the best in the world, but which could be sold at a reasonable price, was daunting one.

The original concept was a coupe configuration, Brock recalled. This design would have come into its own on the high speed circuits of Europe, such as Le Mans and Spa, which was the long term goal.

From an aerodynamics point of view, it was easier to work with the contour of a coupe’s roofline than to contend with the open space behind the windshield of an open car, but time was short; the complexities of fitting doors, roll-up windows, etc. that would be required of the coupe outweighed the aerodynamic benefits so we opted for a simpler to build open car.

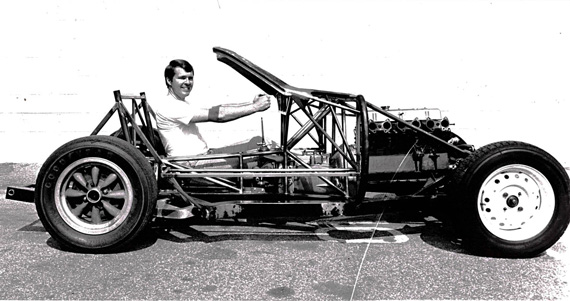

Peter Brock sits in his partially completed TR250K chassis. Note the 9” engine set back and that the specially fabricated intake manifold has now been fitted.

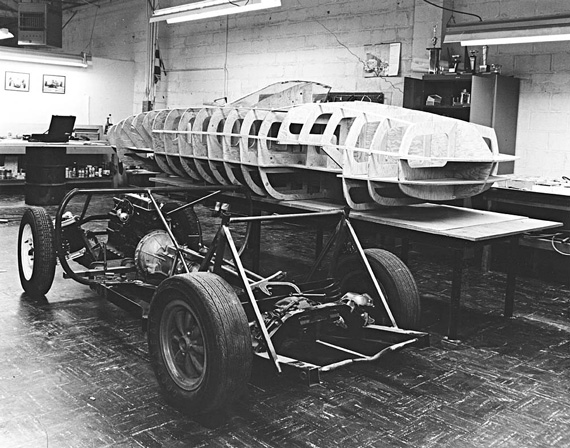

The chassis was a production unit which Kastner set aside and delivered to Brock’s BRE facility:

He (Kastner) just gave me a new bare chassis out of stock and I went from there in laying out the cockpit. All the design and fabrication work was done at BRE by our best fabricator, George Boskoff. We set the engine back as far as practical to improve weight distribution and then built an entire sub-frame of small tubes on top of the stock TR4 chassis to increase stiffness. Later, Kas added all of the suspension, engine and running gear based on his vast experience with the TR-4s.

Detail of the TR250K cowl section fabrication necessary to stiffen the chassis and fit the special windscreen. Very light but complex!

Once the chassis work was completed, the unique K-car began to take shape. The engine had been relocated over nine inches to the rear, which allowed Brock to “place” the driver into the unit and to configure the body and components around this base.

I placed a lot of importance on the layout of the cockpit from a driver’s point of view – as driver comfort allows a certain amount of “relaxation” at speed. I call it “dynamic ergonomics.’ The K-car has more room for driver and passenger than the production Triumph TR4. The high back behind the cockpit was revolutionary in its time; this feature was essential to offset the aerodynamic loss encountered by removal of the roof. As a side benefit we gained useful space for the spare tire, mechanical components and luggage.

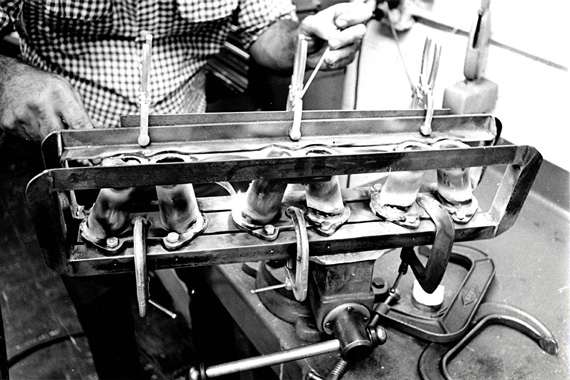

BRE’s master fabricator, George Boskoff, building the triple Weber intake manifold for Kastner’s special 2.5 liter, six cylinder, TR Sebring race engine.

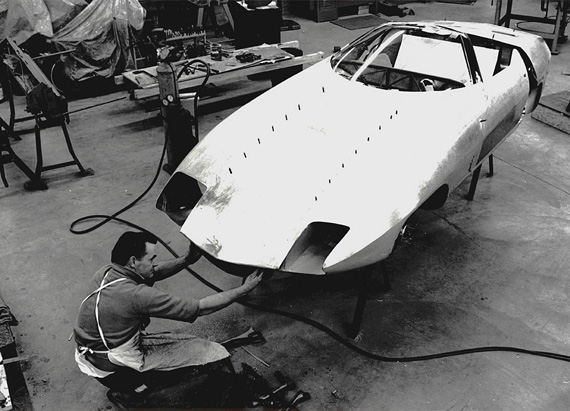

The steeply raked windshield, which is a hallmark of the K-car’s sleek design, was originally seen on another of Brock’s creations, the Hino Samurai. The custom fabrication of the body and most of the intricate work to fit it to the chassis was carried out by Brock’s good friends Don Borth and Red Rose who were also ex-Shelby employees. The flawless paintwork was done by another good friend, Dave Kent. The engine was a standard 2.5-liter Triumph unit with Weber carburetion instead of the less familiar (to the team) fuel injection, which was being introduced as standard on the United States production Triumph TR5s at the time.

The bare TR4 chassis (note the independent rear suspension) in the BRE shop with the finished TR250K wooden buck on the fabrication table just behind. Brock’s stiffening tubular sub-frame has not yet been added.

Brock admits that while he has no record of the time he personally spent locating talent, chasing parts, and soliciting sponsorships, the skilled craftsmen and artisans were all close by. “Times have changed,” he observed. “If I were to attempt such a project today, I would probably have to relocate to North Carolina.”

Red Rose of Borth & Rose Fabrication in Gardena, California fits the partially completed nose section to the TR250K’s main body just weeks before the car’s debut at the 12 Hours of Sebring.

Construction of the K-car became a race against time. Testing consisted of only a single day of testing at Willow Springs before heading off to Florida. The issue of expected aerodynamic lift was solved by the integration of a cockpit adjustable rear spoiler. Some minor engine cooling problems were addressed and rectified once the team arrived at Sebring. The Triumph was officially entered in the event by Leyland Motor Corporation of Teaneck, New Jersey. Driving chores were assigned to Kastner’s top west coast team diver Jim Dittemore, and Bob Tullius, who ran the east coast Group44 team for Triumph. Mike Rothschild was also listed as backup.

#47 in the Sebring paddock with all its quick-access panels open for inspection. Almost every panel could be easily removed with ball-lock “quick-pins” for ease of service.

An unfortunate mechanical failure sidelined the Triumph 2 ½ hours into the event. One of the rear wheels, which had been sourced from one of the first Jim Hall Chaparrals, failed causing the car to spin and damage the rear suspension. There was no way to make the repairs needed and with no spares the Triumph was withdrawn from the race. “We had used too fine a radius when we re-machined the wheels to accommodate the Triumph hubs,” Brock recalled. “This caused a stress-riser and a crack occurred on the stud circle.” At the time the failure occurred, the Triumph was far ahead of its competition. “We proved that the car was fast . . . much faster than anything we’d have ever faced in the SCCA’s Class C-Production.”

Kas Kastner, third from end on left, with his team at Sebring 1967. Designer Pete Brock is on the end, left side.

Peter Brock’s random thoughts on the K-car:

I was looking for a challenge—the K-car project really appealed to me. What I’d created was pretty unusual for its time with it swept-back windshield and wedge-shape body incorporating a high rear end. The design was different from anything else in the early sixties, but the lines look very contemporary today. The K-car was ahead of its time.

Triumph driver Jim Dittemore at speed on the Sebring circuit. Note the K-car’s rear spoiler has been raised for increased down-force and high speed stability in the turns.

The environment at Triumph headquarters in England was unsettled. The Standard Triumph Company had been incorporated into the Leyland Group in December 1960. I don’t believe anybody in upper management in England was aware—or would have cared—that a Triumph sports car was taking on the best in the world in a major endurance race. After Sebring, they got a look at the K-car and realized there was some proven appeal. They decided to drop whatever they originally had planned for the TR7 and somehow ‘adopt’ what Kas and I had created . . . why they didn’t just put me on retainer to re-design their existing chassis and do a real production version of the body is a question I can’t answer; maybe it was just because we were too ‘American’ to fit the Brit’s system.

Rear view of the TR250K shows the advanced shape of aerodynamically superior rear deck which improved air-flow over the car’s body but also would have provided more luggage space and greater capacity for the fuel tank and spare tire. The rear spoiler is in its normal closed position.

The K-car appeared on the cover of Car and Driver magazine, as promised by Leon Mandel, together with a feature article on how Triumph erred by not producing the car. After a brief tour on the show circuit, the K-car disappeared from the limelight. Little is known of its activities until it appeared some years later,painted red, in storage at the Blackhawk Museum in northern California The K-car was subsequently purchased by the Pat Hart family and is racing once again. . . (Story to be continued in a future article)

********************************************************************************************

If you weren’t aware, today Peter Brock designs unique classic car transportation modules…here is an example of a recent product from Aerovault…

More information can be found by clicking on the below ad.

Having spent 4 days hosting Peter at Kansas City’s Art of the Car Concours this summer, and having dinner with him and Gayle last week at Prbble, I was blown away by Peter, the man…. I knew of his fabulous Daytona Coupe, and his revolutionary car hauler designs, and the K car knocks it out of the park! (How unfortunate that Triumph chose to go with the ugly duckling TR 7 instead!)

But the most impressive thing I have observed about Peter: you look up the word “gentleman” in the dictionary, and there is a picture of Peter.

What an amazing, talented man!

Gary Krings

What an incredibly accomplished man!

there was the most condescending letter i have ever read–and i’m serious–published in one of the bigname usa magazines; it was from some p.r. rep at triumph explaining to us peons that because of the complex usa regs which we couldn’t be expected to understand, it was simply impossible to even consider producing this car. i wanted to crawl thru the magazine and punch him in the face. ddiligent research could probably find the letter. they’d be building the offspring of this car today if they’d had the sense to build it then. to use my copyrighted phrase, ‘there’s a reason God put the brits on an island.’

Everyone knows that Peter did the Cobra Daytona coupe, but few realize the breadth of cars he has designed. It didn’t hurt that he started on the team that designed the split-window Corvette. Many more followed. He made the lowly Datsun 810 into a race winner and his BRE livery on the car even made the ugly duckling look sporting. A great designer and a real enthusiast. We all have been to Le Mans, Daytona and Sebring, but Peter’s enthusiasm leads him as far afield as Pikes Peak every year. We also have to commend Gayle, who takes more than her share of the load. For all you dudes who are towing stuff around, Peter’s Aerovault trailers are every bit a slick as his car designs.

Pete is a great designer and enthusiast. He signed the dash of my 66′ GT350 replica following an amazing presentation he made to a group here in Chicago last year. He and Gayle are a real treasure and carry the burden of advanced design as did my Uncle Alex and Aunt Chrissie. Getting the deserved recognition while upright on this earth is a testament to the genius at work in Pete’s amazing body of rolling artwork.

While I like the lines of the Cobra Daytona, and sure am not a fan of the TR7, coupes especially, as the owner of a real TR250 this TR250K looks to me like a design exercise gone very wrong, with features out of balance with each other. I much prefer the Michelotti TR4-5 design, which is a really good thing since there is only one K. Brock’s other projects were a lot more successful.

Mr. Brock is obviously a legend (and I’m a big Datsun Roadster fan as well); but I can’t say I’m a fan of the looks of this car. It might be aerodynamically correct; but it’s not all that attractive.

One other thing. There’s a mention above of ‘United States production TR5s’ and a suggestion they might be fuel injected. There were no US TR5s (we got the TR250, which was carbureted and not fuel injected).