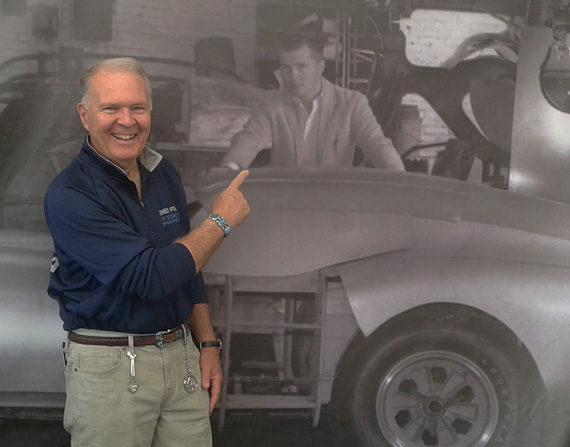

Fifty years on, Peter Brock poses with a photo of Peter Brock and the prototype Daytona. Our story deals with the first of five Coupes built in Modena. Courtesy Peter Brock collection.

By Peter Brock

As soon as the first Daytona Cobra Coupe, CSX 2287, was completed and tested successfully at Riverside Raceway on February 1st 1964, Carroll Shelby decided to build five more. He felt he had a score to settle with Enzo Ferrari and finally had the weapon to do it. The Daytona’s radical design had been so controversial within the Shelby organization that most of those employed there figured Shelby’s plan to race in Europe against Ferrari would evaporate as soon as the first Coupe was tested and found to be a failure. That resistant attitude changed dramatically as soon as test driver Ken Miles called from Riverside trackside to inform Shelby that he’d shattered the track’s lap record by 3.5 seconds!

The Daytona Coupe’s controversial form was based on pioneering studies and complete running prototypes completed by German aero scientists Wunibald Kamm and Reinhold Koenig von Fachsenfeld in the late 1930s. Their work was unknown in America and most of their data had been lost or destroyed during the war. Only my chance discovery in 1957 (while working for GM styling) of some of their notes, found in the GM Tech Center library, intrigued me enough to save and use their ideas six years later when the opportunity arose to design a new GT Coupe for Carroll Shelby. The concept of using a roofline with minimum downward curvature at the rear combined with a severely truncated tail went against the accepted “common knowledge” that a tapering “teardrop” shape was ideally suited to racing cars. Later, others in Italy had also discovered the advantages of keeping boundary air flow attached to a car’s body but only the Zagato-bodied Alfa Romeo TZ1 from 1964 had really followed the formula correctly at the same time I was designing the Daytona. Hardly anyone in America had seen anything like these forms so the concept was almost universally rejected at that time.

Five Kamm tailed Coupes. Papers at the GM library on the Kamm experiments tipped off Brock as early as 1957. Note the different rooflines. The second car in line (CSX2286) has a better line at the rear!

Let’s build them across the street from Ferrari

Shelby figured he’d need at least six Daytona Coupes to challenge Jaguar, Aston Martin, Ferrari and even Ford for the World’s GT Championship. A rule change, instigated by Ferrari in late 1961, called Appendix J in the FIA regulations, allowed manufacturers to create entirely new bodies on existing chassis. Ferrari’s 250 GTO (Grand Turismo Omlogato) was the result. With a top speed of some 180 mph the GTOs had been almost unbeatable since 1962.

Shelby figured he’d need at least six Daytona Coupes to challenge Jaguar, Aston Martin, Ferrari and even Ford for the World’s GT Championship. A rule change, instigated by Ferrari in late 1961, called Appendix J in the FIA regulations, allowed manufacturers to create entirely new bodies on existing chassis. Ferrari’s 250 GTO (Grand Turismo Omlogato) was the result. With a top speed of some 180 mph the GTOs had been almost unbeatable since 1962.

Left, the Ferrari factory. Why not build the Daytonas in their back yard? Photo by Hugues Vanhoolandt.

There was only one slight problem. The Shelby team was so small at that time that once the principal members of the crew that had built the first Daytona departed to support the team’s Cobra roadsters in Europe, there was no one left in California to build the next five! Shelby called friend Alejandro de Tomaso in Italy to see if he could make arrangements to have five more Daytona bodies fabricated at one of several small carrozzerias in Modena. In a few days DeTomaso called back saying Carrozzeria GranSport was willing to do the job.

The Daytona’s bare AC chassis were completed in Thames-Ditton in the UK and flown to California to have their 289 Ford, Shelby-built racing engines, running gear, plumbing and wiring installed at the Shelby shop in Venice, California. Since the first Daytona Coupe had been built in 90 days with as much internal structural design work done by the fabricators on the shop floor as I had done to create the external form for the new Coupe, there were actually very few detailed drawings to guide those who would build the next five cars. My original drawings had been done in quarter scale with the understanding that all further work would be done at Shelby’s. The original plan had been to build a second Coupe alongside the first so the second chassis, CSX2286, could be used as a three-dimensional template to assist those constructing next four chassis and bodies as the bare frames arrived from the UK. When the reality of the situation became apparent (that the first Coupe would be racing in Europe and the second chassis would be needed in Venice as a template) it was decided that the next five chassis would still be completed in Venice and then be flown to Italy for completion at GranSport.

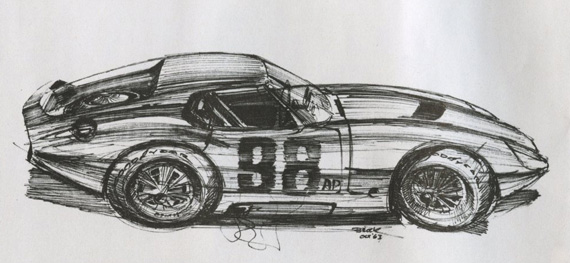

Brock made this sketch in 1963 and recalled, “Note the movable rear wing (which I called a ‘ring airfoil’). Obviously it didn’t make it onto the finished car. If it had we’d have been MUCH faster!”

Brock made this sketch in 1963 and recalled, “Note the movable rear wing (which I called a ‘ring airfoil’). Obviously it didn’t make it onto the finished car. If it had we’d have been MUCH faster!”

All in the translation

That created a new problem. Because my drawings were scaled in inches and the Italians worked in millimeters and they had no completed car to copy, they would have to solve the problem in their own inimitable way. Fortunately that proved far less complicated than expected but it did create some interesting variations on my theme. The Modenese method of creating race car bodies back then was more of an art form than a formal engineering exercise. Instead of using accurately lofted drawings supplied by the chassis’ designer, only a rough outline indicating the expected external form was supplied allowing the artisan craftsmen in each carrozzeria to refine the chassis designer’s basic idea into their own creations.

When Cobra chassis, CSX 2299 (the first to be shipped to Italy) arrived at Carrozzeria GranSport the body craftsmen looked at my four-view quarter-scale drawings (drawn in inches) and realized that without some practical method to convert its Anglo dimensions into Latin millimeters the plans were essentially useless! Their only real value was in the visual outlines of the body shape, which in turn proved questionable as the Modenese initial reaction to my unfamiliar form was the same as all previous viewers at Shelby’s. Since it was accepted local practice in Modena to “design” their automotive own forms based on a rough outline received from the chassis builder, the artisans at GranSport had no misgivings on “improving” the lines I’d supplied. Since almost all Italian automotive Coupes from that era were based on the then prevailing theory that a graceful “teardrop” shape, with a long sloping roofline, ending in a pointed tail would be most aerodynamically efficient, my Daytona’s lines were viewed with some skepticism. Most of the beautiful Italian GT interpretations of the Art Nouveau “streamline” style had been in vogue in Europe since the mid-1920s when a Hungarian visionary, Zeppelin designer Paul Jaray patented and applied his aeronautical findings to automobiles. His ground-breaking work had been accepted as gospel by many of the great names in the automobile world.

Coachbuilding “per occhio”

The talented craftsmen at GranSport couldn’t really ignore the strange lopped off tail in my design but felt the roof line could certainly be “improved” by moving its highest point (over the driver’s head) several inches forward, so that it could meet the top of the windscreen (whose position on the chassis somehow didn’t match my drawings!) In short the GranSport artisans built their first Daytona Cobra Coupe with a rather Ferrariesque roofline! This variation was partially the fault of our young fabricators in Venice, California. They had inaccurately positioned the main transverse cowl-support hoop higher on the lower main frame tubes so the top line of the cowling it did not match the chassis drawings by about an inch! That mistake raised the entire windscreen a corresponding amount, which ironically made sense to the Italians, because that made it easier to form the roofline more to their taste.

The very first Cobra coupe remains unrestored with a very fascinating history. It is now at the Simeone Foundation near Philadelphia. Jonathan Sharp photo.

When crew chief John Ohlsen and I arrived in Modena to check progress on CSX2299 the “Italian” roofline on this first GranSport built Coupe it was so different than our California built prototype we were astonished; it was constructed much differently than we had expected. Of course we asked to see my drawings to compare, but then had it explained by the only English speaking fabricator in the shop that his compatriots had no way to convert our dimensions to millimeters. Instead they were going “per occhio” (by eye) as they usually did and were actually quite proud of the result. There was no doubt the new Coupe was a stunningly beautiful piece of work but I was concerned that the Italian’s new roofline wouldn’t be quite as aero-efficient as the original (in fact this one “Ferrari roof” car proved to be 3-4 mph slower). What pleased me most, however, was the Italian’s interpretation of my headlight design.” The next four cars were far closer to the prototype. What pleased me most, however, was the Italian’s interpretation of my headlight design. Instead of keeping the transparent headlight covers on the upper part of the front fenders, as I had done on the prototype, they’d brought the transparent edge of the covers down over the “highlight line” of the front end which gave a far smoother more elegant solution.

After we’d double-checked the dimension of the main cowl tube and discovered our California fabrication error was partially the cause of the car’s “new look” we laughed and accepted the new roof line in good humor. We then invited the crew out to dinner to celebrate the good fortune of our collective errors and their improved headlights with a fine bottle of local Lambrusco. Working with the Modenese was such a delight. Unlike many journeyman craftsmen in America and the UK, who were accustomed to rigidly following the lines on an engineering print and would not have known what to do when given such a confusing set of guidelines, the Italians simply improvised using their own good taste to solve the problem and created great art in the process.

Making Ferrari furious

We didn’t know it at the time but Mauro Forghieri, Ferrari’s designer/team manager had paid a visit to GranSport a few days before we’d arrived to check on csx2299. Years later Forghieri told us what Ferrari’s reaction was. Naturally, Forghieri had been at Daytona with his team when our prototype broke the lap record and then proceeded to walk away from his vaunted GTOs. Enzo was not present, as he seldom attended races, but he got an earful when Forghieri returned from Florida! When Forghieri learned that the bodies for Shelby’s Daytonas were being constructed right in Ferrari’s backyard, he went to investigate. He was less than pleased when he learned that his countrymen were abetting the enemy! When he confirmed this news with Ferrari, telling him,“I believe we are in deep trouble,” the patriarch was furious. He vowed he’d never give any more work to GranSport!

A winner right off the trailer

CSX 2299 was barely finished in time for Le Mans. It was trucked up to a Ford garage in Paris on a flatbed, our base of operations prior to Le Mans. There John Ohlsen fitted the freshly painted Coupe with its new engine, running gear and then carefully prepped it for the 24 Hours. Because there was no time left to test it on track after scrutineering, we took it to the small airport behind the Le Mans grandstands and ran it up and down the main runway a few times to check for leaks. It would start the race never having turned a wheel in anger. Incredibly, 24 Hours later Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant would celebrate their co-drive on pit lane after winning the GT class for Shelby American. It would be the first time, but not the last, that a Daytona Coupe would defeat Enzo Ferrari’s works team of 250 GTOs in Europe. Carroll Shelby was more than pleased.

Today CSX 2299 is owned by the Miller family in Salt Lake City, Utah. They graciously agreed to send it to Goodwood a few weeks ago so it could join the other five Coupes, invited by Lord March, in celebration of the Daytona’s winning the World’s GT Manufacturer’s Championship in 1965.