By Pete Vack and Gijsbert-Paul Berk with photographs by Dale LaFollette

Thanks to the Portland, Oregon Art Museum and Ken Gross

When Dale LaFollette returned with the following photos and a wonderful brochure about the new show at the Portland, Oregon Art Museum, we were impressed with the selection and approach. “Shape of Speed…demonstrates how auto designers translated the concept of aerodynamic efficiency into exciting machines.” As our Senior Editor Gijsbert-Paul Berk has already covered this in detail via his four-part series on Concept Cars and Streamlining, there is little else to be said.

Or is there?

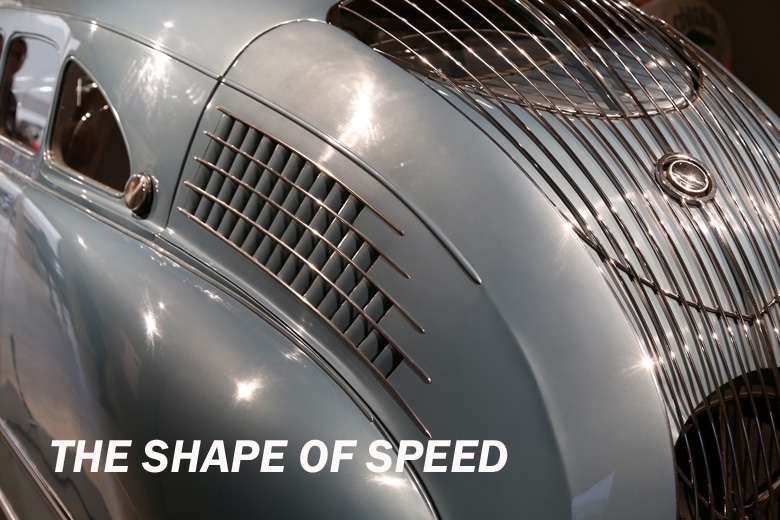

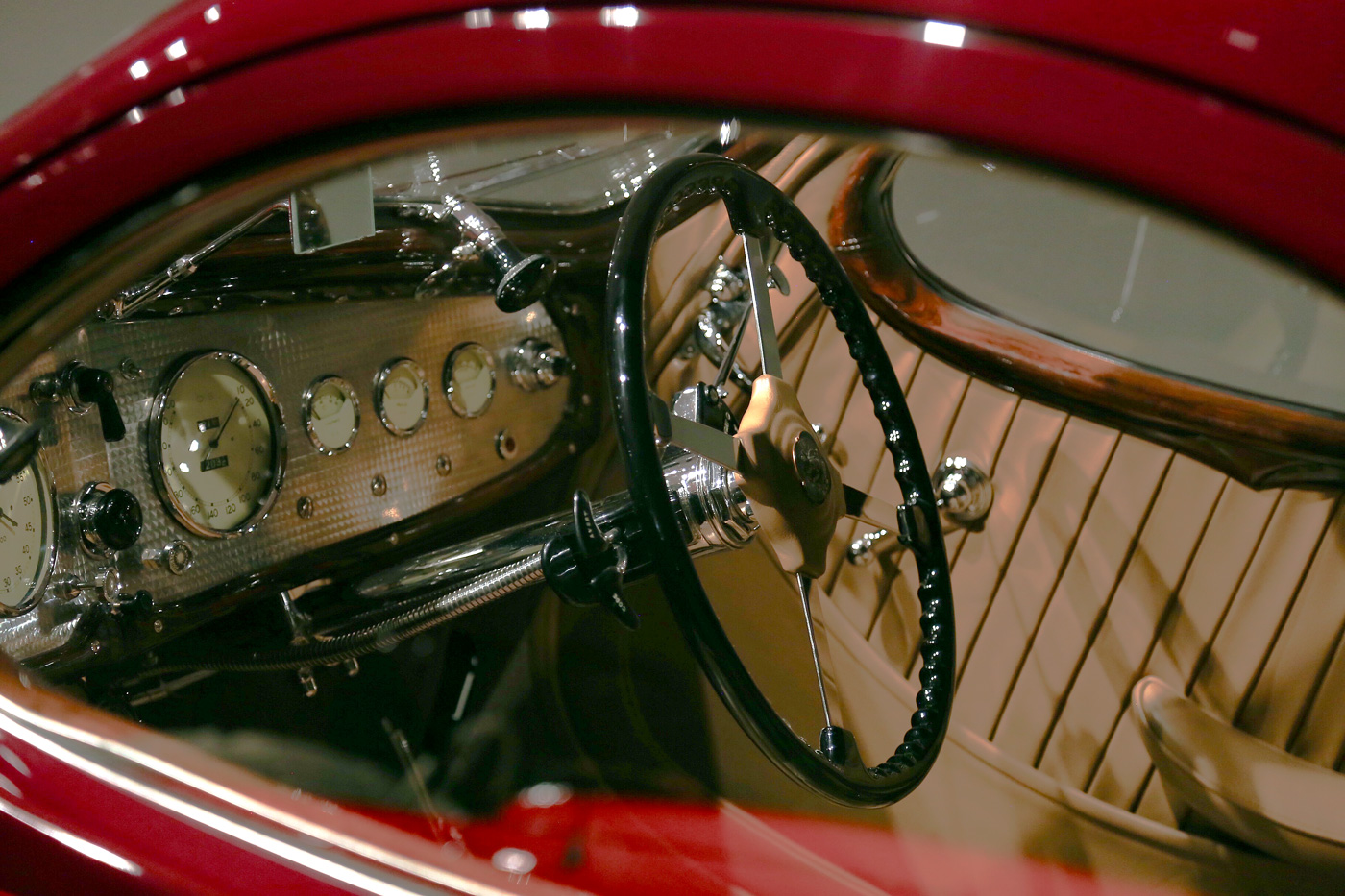

Lafollette’s camera work brought out the amazing intricate detail work that adorned many of the streamliners despite the fact that even then, they probably knew that such trimwork often increases air turbulence. Yet some of the most fascinating and artful examples of exterior trim and chrome reside upon the flanks of streamlined bodywork, particularly on the American cars.

Second, we organized the cars by country, better able to see and appreciate the different approaches to streamlining taken by different nations, and found that the Portland Art Museum Exhibition was notable as there were no cars or designs from Great Britain. Why was this so? We asked our Senior Editor to comment:

At first sight is seems indeed amazing that the British car and coachbuilding industry was so lukewarm about streamlining during the mid-thirties. All the more so because British scientist and aircraft engineers of that time knew quit a lot about aerodynamics. Fans of historic aviation, among the readers of Velocetoday.com, will certainly remember the magnificent Supermarine S.6B, S1595 seaplane, which in 1931, piloted by Flt. Lt. John Boothman, won the Schneider Trophy, for record breaking high speed flights with a speed of340.08 mph (547.19 km/h). The plane was powered by a Rolls-Royce engine, developing 1,900 hp (1,417 kW). Reginald J. Mitchell, the brilliant chief engineer, then employed all his knowledge and experience to develop the iconic Spitfire WWII fighter plane. Most of us will also remember the impressive, large and streamlined Golden Arrow Sunbeam and Napier Bluebird record cars in which (Sir) Henry Seagrave and (Sir) Malcolm Campbell used to pursue their land speed record ambitions. In 1935 Cambell’s last Bluebird car was clocked in two passes on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah at an average speed of301.337 mph (484.955 km/h).

But for British manufacturers of passenger cars, even those who made powerful premium models such as Rolls-Royce, Daimler and Bentley experimenting with aerodynamic body shapes had no priority. In a sense this is understandable, because contrary to the French Routes Nationales, the American highways, the Italian Autostrada and German autobahn, the roads in Great Britain did not permit long journeys at high speeds. On the narrow and sinuous British roads acceleration was much more important than a high top speed to attain a high average. The 1939 Aston Martin Atom, designed by Claude Hill, was one of the few attempts at streamlining a sports car.

In addition, many British clients of luxury cars also cars considered streamline bodies rather impractical. The sloping roofline often limited headroom for the rear seat passengers and prevented them wearing a bowler hat when being driven by their private chauffeur. In about 1935 Roy Fedden, a famous aircraft engineer, commissioned Park Ward to produce a streamlined body after his design; he offered them as part of his payment the licensing rights. The Fedden design had cycle type front wings. These looked very sporting but also made the front of the body very dirty when driving on muddy roads, the fastback rear end also reduced the luggage space. As a result, Park Ward reverted to a more conventional design.To see the Fedden Bentley, click here.

Below then is a selection of the cars displayed at the Portland Museum, sans entries from the U.K. Note the chromework on the American cars (which reached its ostentatious peak in the late 1960s).

Italy

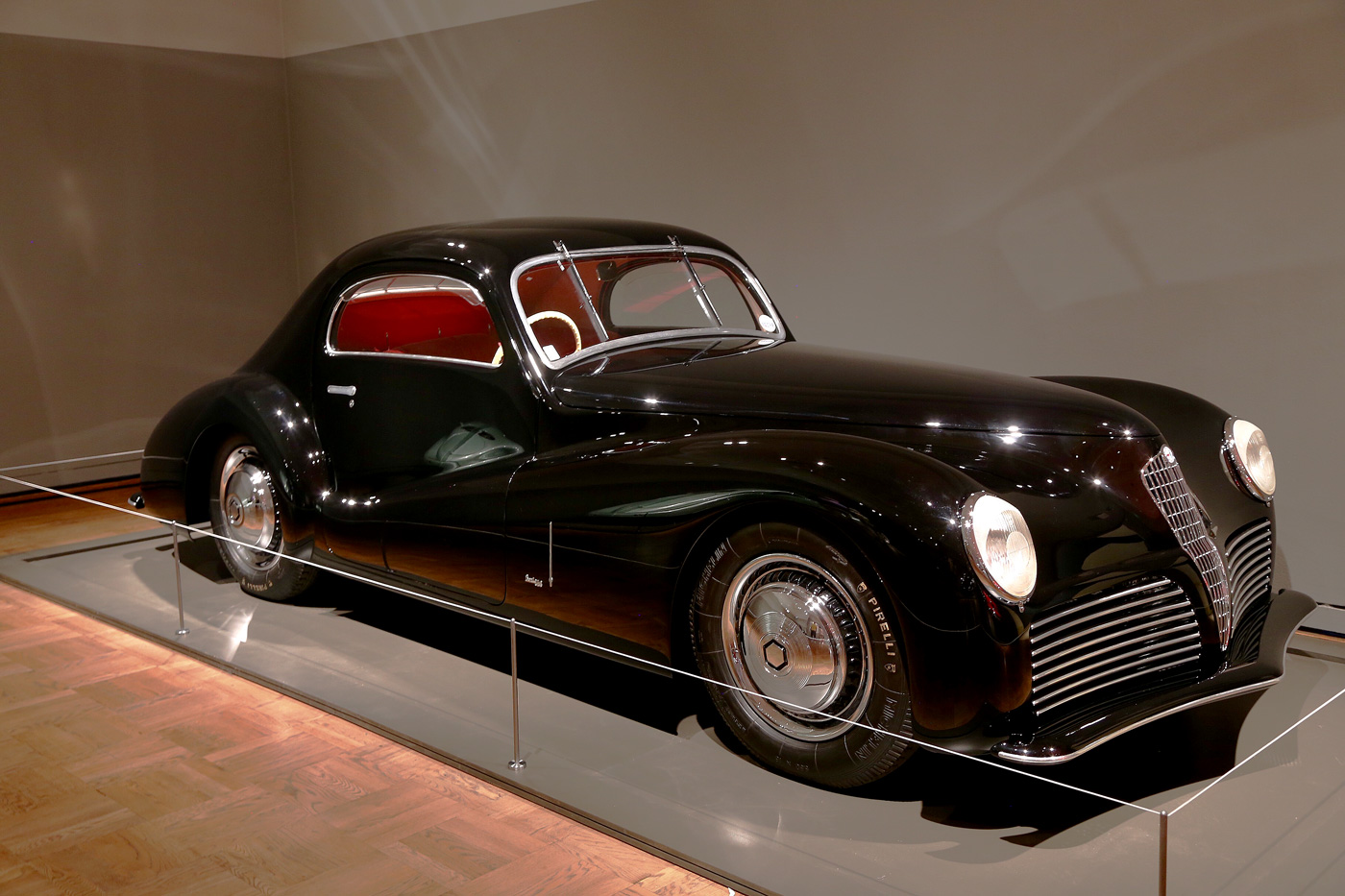

1942 ALFA ROMEO 6C 2500 SS BERTONE BERLINA

Like Germany and France, Italy was ahead of the curve when it came to streamlining. Though the Museum presents only one Italian car, it is this impressive 6C 2500 Super Sport. Bertone constructed the car to a design by Mario Revelli di Beaumont and initially delivered to Oreste Peverelli, a car dealer from Como, Italy. It was eventually purchased and completely restored by Corrado Lopresto. Devoid of any ornate trim, the traditional vertical with two horizontal grilles serve to compliment the elegant design.

Czechoslovakia

1938 TATRA T77A

Th only entry from Czechoslovakia, the Tatra is perhaps the most radical of the cars selected for the Portland Art Museum. Hans Ledwinka engineered the car with streamlining concepts of Paul Jaray. The Tatra featured a full undertray, and plenty of attention was given to reducing air turbulence throughout the body. Hence, no fancy grilles, or gewgaws.

France

Always a leader in both technology and engineering, France was also in the forefront in developing streamlining for both the small production exotics such as Talbot and production line cars such as the Panhard Dynamics. In addition to the three cars below, the Portland Art Museum displayed a replica Bugatti Aérolithe T57, but we allowed the Bugatti to have its own page (read Everyone’s Favorite Bugatti). The Figoni et Falaschi Delahaye Roadster and the Talbot Lago are always crowd pleasers, but the rare one is really the Panhard & Levassor Type X81 Dynamic, which featured a type of wrap around windshield, central steering, covered headlights, and coachwork welded to the chassis creating a unibody. There was simply nothing like it, anywhere.

1938 DELAHAYE 135M ROADSTER

Richard Adatto wrote, “Joseph Figoni took modern streamlining to the next level by allowing the optimal aerodynamic shape to dictate the styling. Instead of pontoon fenders that protruded from the car’s body, Figoni found a way to incorporate them into the body, heightening the impression of a singular, flowing form.” It is believed that just 11 of these voluptuously bodied Salon de Paris roadsters were built, on short- and longwheelbase Delahaye chassis. This 135MS, chassis number 49169, has a 3.5-liter, 6-cylinder engine. From Shape of Speed catalog.

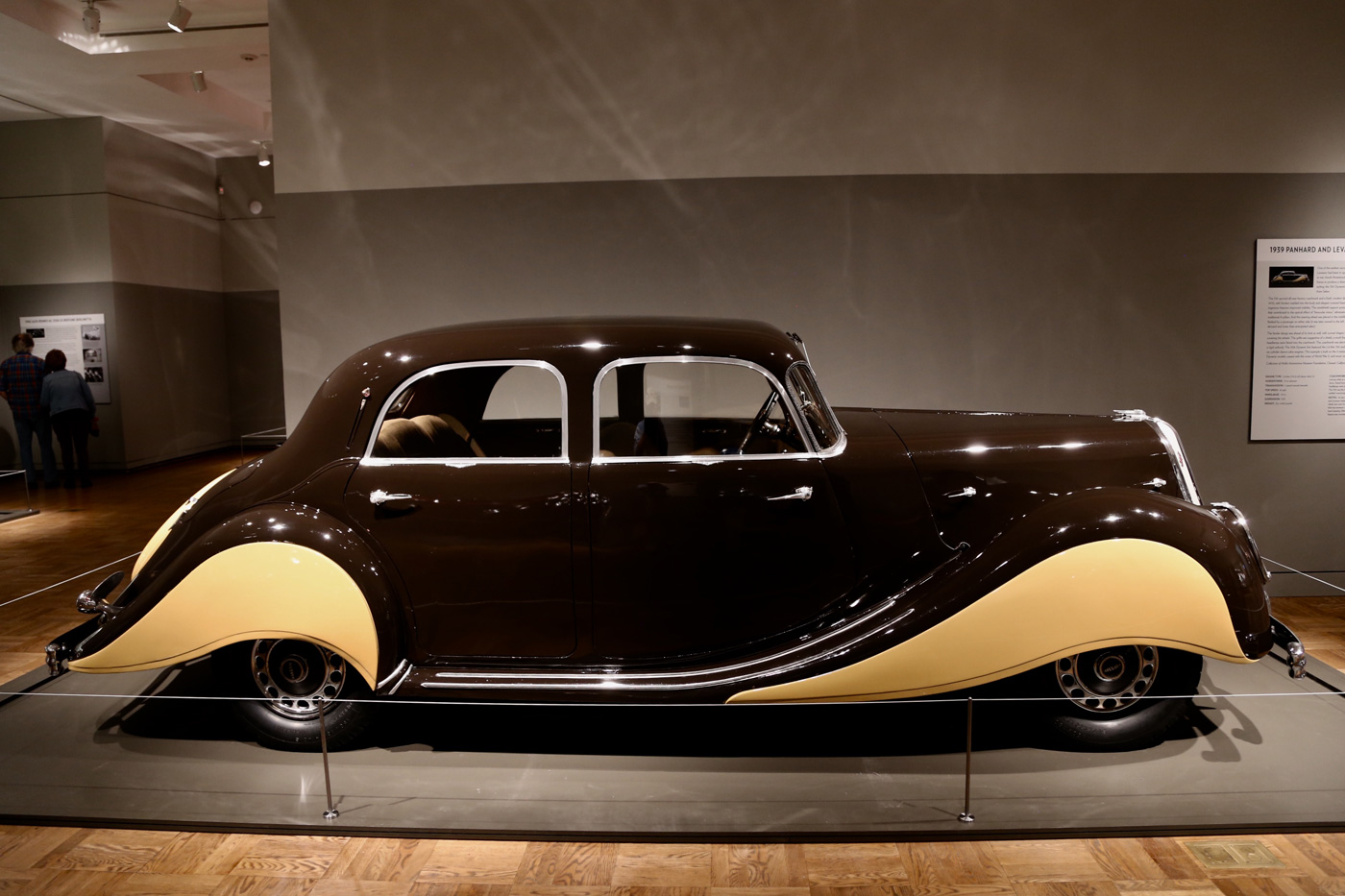

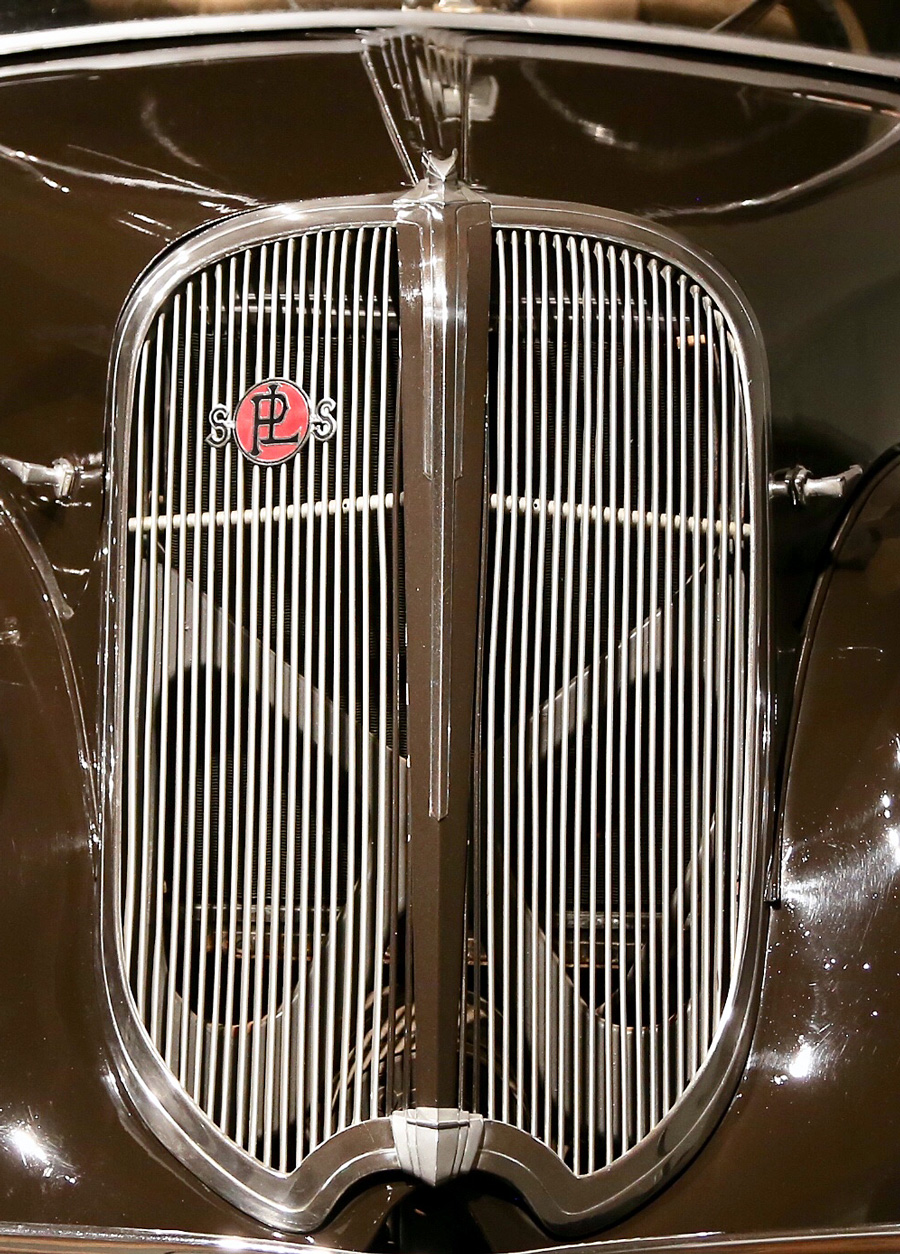

1939 PANHARD & LEVASSOR TYPE X81 DYNAMIC SEDAN

With the introduction of its new Dynamic in Types X76 and X77 at the 1936 Paris Auto Salon. Panhard & Levassor stretched even further in the true spirit of aerodynamic styling with its new X81 two years later, at the 1938 Paris Auto Salon. With a radically new and modern look that emphasized the company’s strengths and individualistic approach, the model lineup for the Dynamic series separated itself from all other offerings on the market that year. The X81 had all-new factory coachwork that differed greatly from its predecessors. A fresh, modern design melded the fenders into the body in a sweeping fashion. From Shape of Speed catalog.

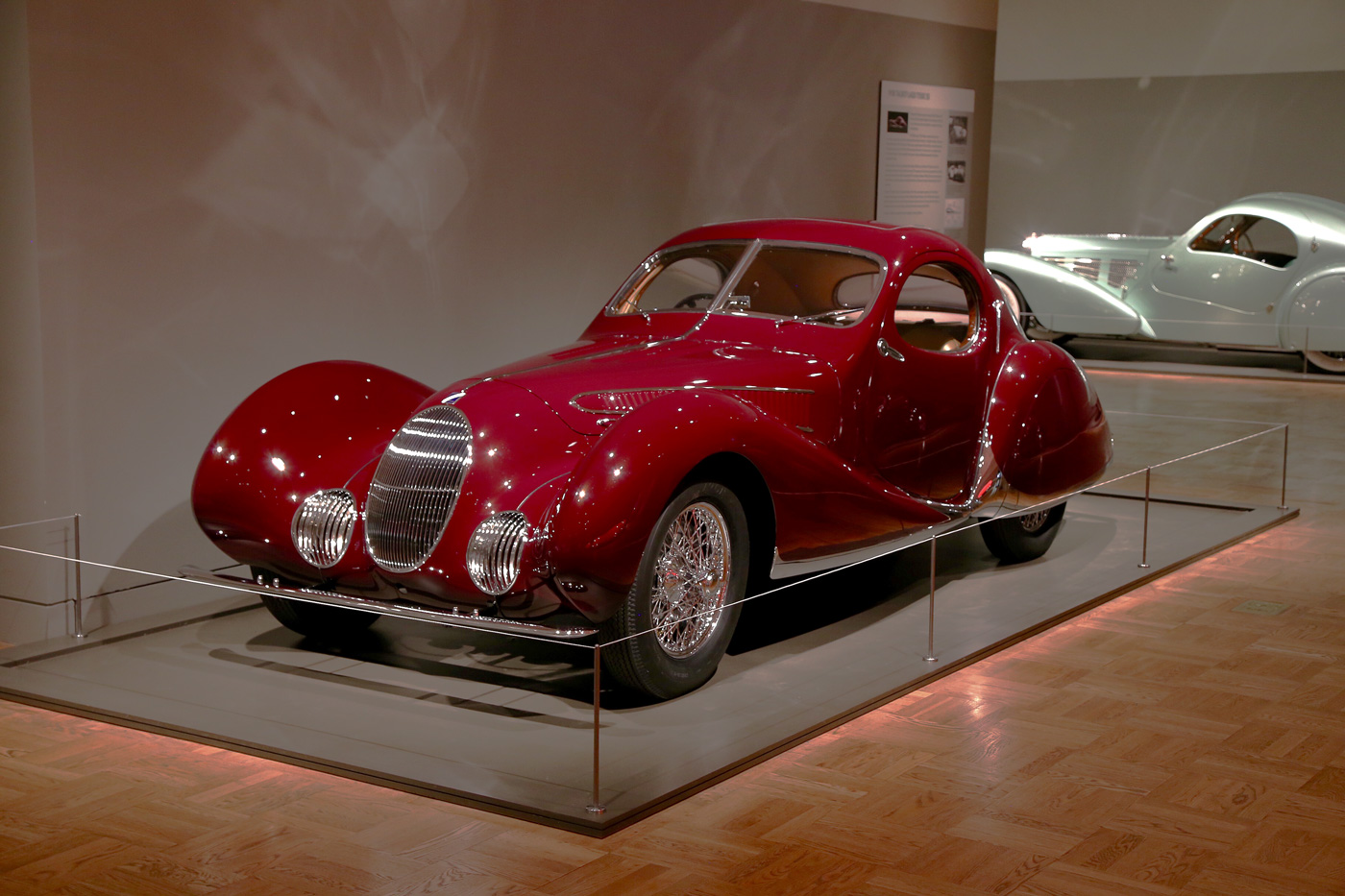

1938 TALBOT-LAGO T-150-C-SS

This example of a Talbot Lago was the first produced and one of three built with aluminum alloy coachwork, was used in 1937 to publicize the reliability and the elegance of its Figoni & Falaschi coachwork. It is unique in several ways, thanks to its lightweight body, fold-out front windscreen, and competition-style exhaust headers. The single blade, aviation-style bumpers perfectly complement this car’s curvaceous shape. From Shape of Speed catalog.

Austria

The town of Steyr, Austria, gave its name to Steyr, a manufacturer of bicycles, armaments, and cars. In 1917, Steyr recruited Hans Ledwinka, later the designer of the streamlined Tatra, to establish the automomotive segment of Steyr, which along with the Gmünd Porsches, was one of the few cars made in Austria. In 1934, Steyr merged with Austro-Daimler-Puch to form Steyr-Daimler-Puch.

1939 STEYR 55 “BABY”

The public first saw the fastback Steyr Baby at the 1936 Berlin Motor Show. Its rounded front fascia resembled a miniature Chrysler Airflow. The headlights appeared to be high because the car itself was so low. The Model 50 compared favorably with the VW and outpointed it in several categories. Despite its shorter length, the Model 50 offered better seating, suicide front doors, and more luggage capacity than the Beetle. From Shape of Speed catalog.

Germany

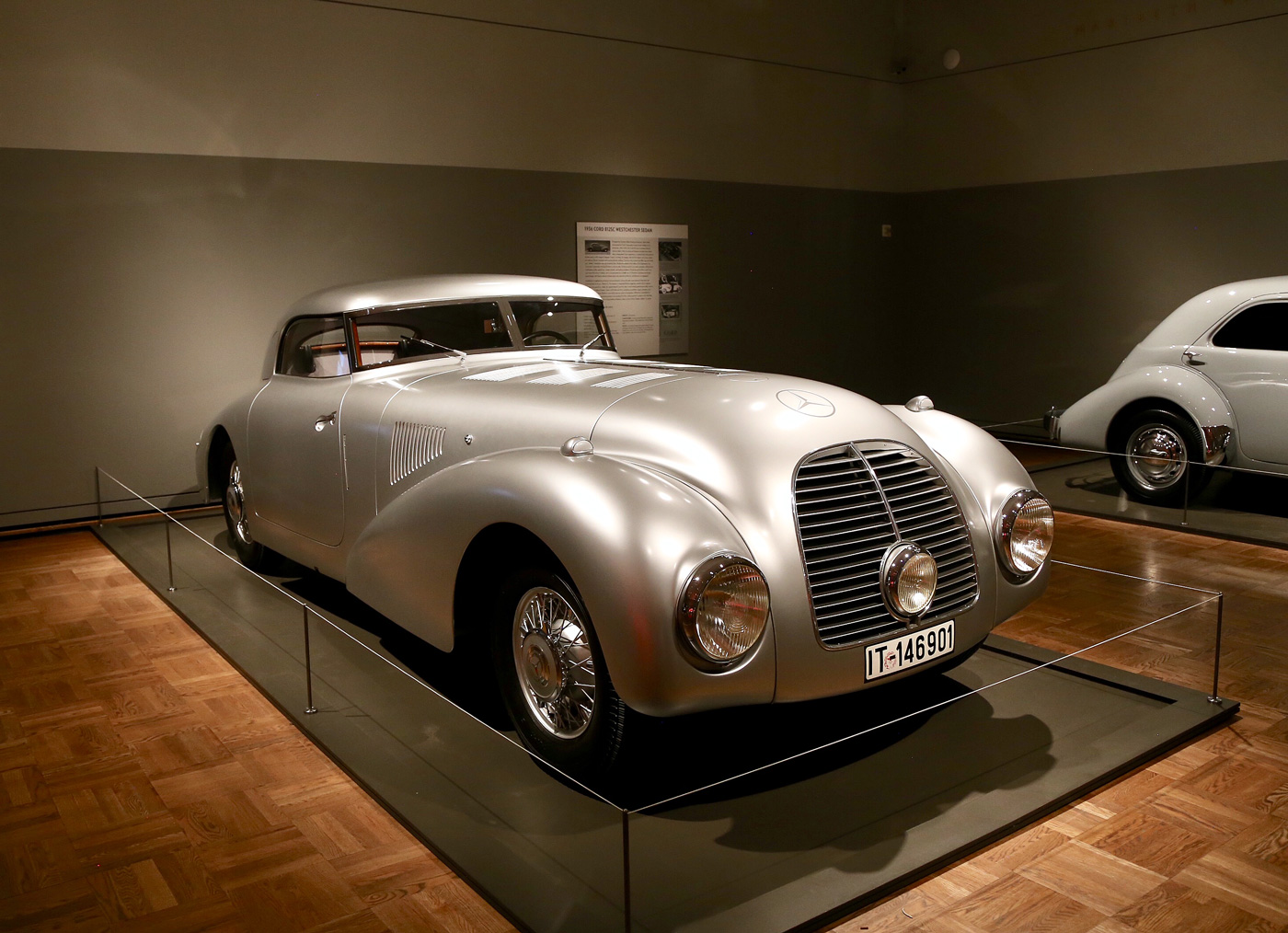

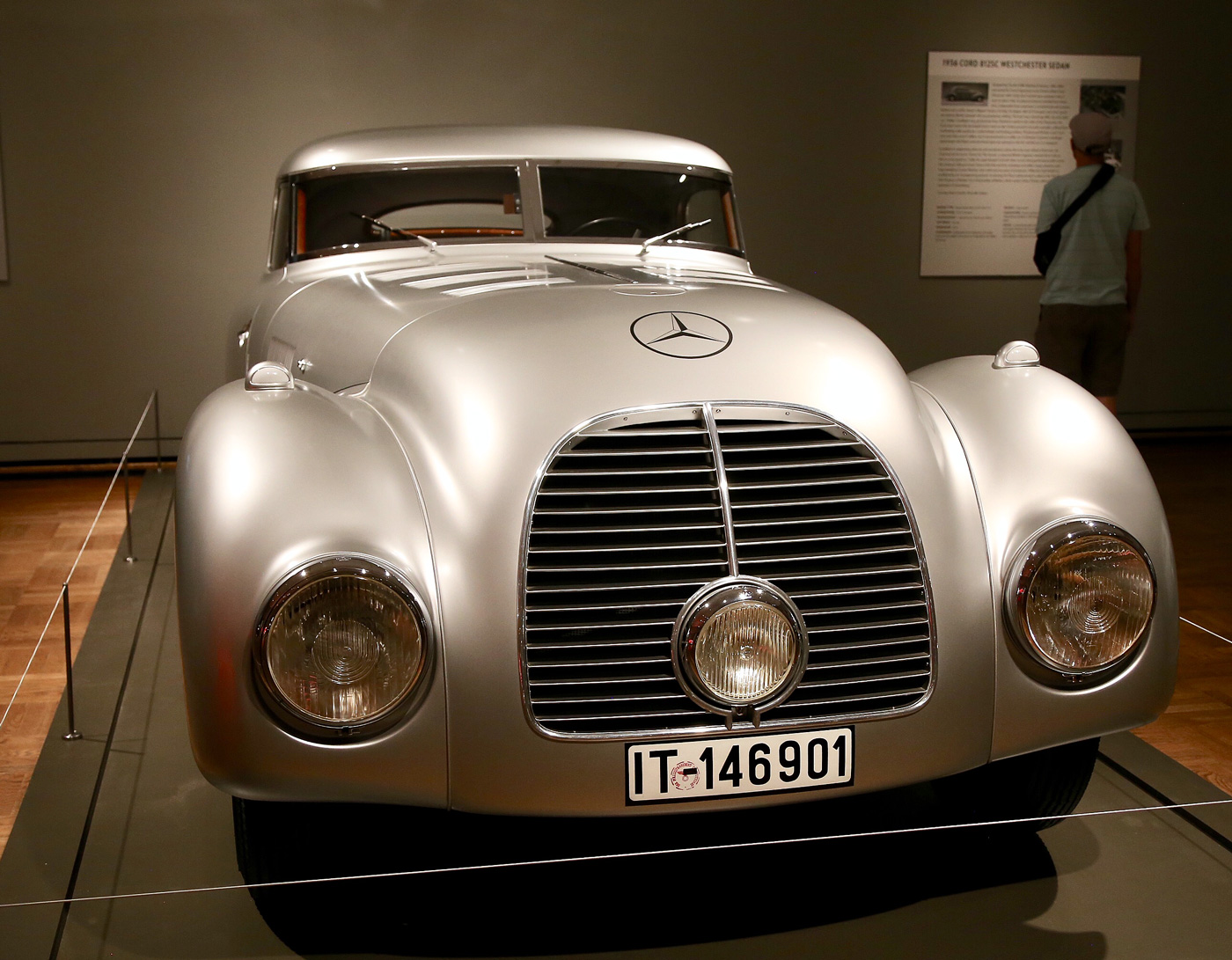

With Rumpler, Kamm and others, Germany was experimenting with streamlined shapes from the early 1920s. Most designs, however, seem heavy handed, but nonetheless lacking wind-disturbing frills. The Portland Art Museum presented this unusual factory re-creation from the Daimler-Benz Museum.

1938 MERCEDES-BENZ 540K STREAMLINER

For years, faded black-and-white photos of a streamlined 540K Mercedes-Benz coupe tantalized historians. Seemingly lost for all time, little was known about this unique car, save that it was specially built as a test vehicle for the German branch of the Dunlop tire company. Its designer was Hermann Ahrens, who penned the elegant 540K Special-Roadsters built by Sindelfingen

Little more is known about the streamliner, except that it was used by a U.S. serviceman after the war, then returned to Mercedes-Benz in the 1950s. After this date its bodywork was removed and most of its mechanical components were taken off and lost. Following the chassis’ rediscovery, restoration technicians at Mercedes-Benz elected to build a new body using traditional methods. From Shape of Speed catalog.

United States

The selection of 17 cars included in the exhibition, the majority were America. The mid-thirties witnessed a wonderful variety of aerodynamic cars, including the Bendix, Airomobile, Hoffman and the influential Chrysler Airflow. The Americans were also keen on adding brightwork, in many cases surpassing the French with frills and non-essential but delightful designs, none more so than the Stout Scarab.

1934 BENDIX SWC SEDAN COURTESY OF THE STUDEBAKER NATIONAL MUSEUM

Although the Bendix (an automotive empire) prototype was designed about the same time as the Chrysler Airflow, there was no connection between the two. Ex-Fisher body designer William F. Ortwig did the styling, but he had no idea what the Chrysler Airflow would look like when he penned the SWC in 1932, so any resemblance is purely coincidental. The prototype was shipped to Europe, where the car was shown to several manufacturers including Bentley, Bugatti, and Renault, to encourage them to purchase Bendix components. There doesn’t seem to have been any attempt to manufacture and sell it as a futuristic car. From Shape of Speed catalog.

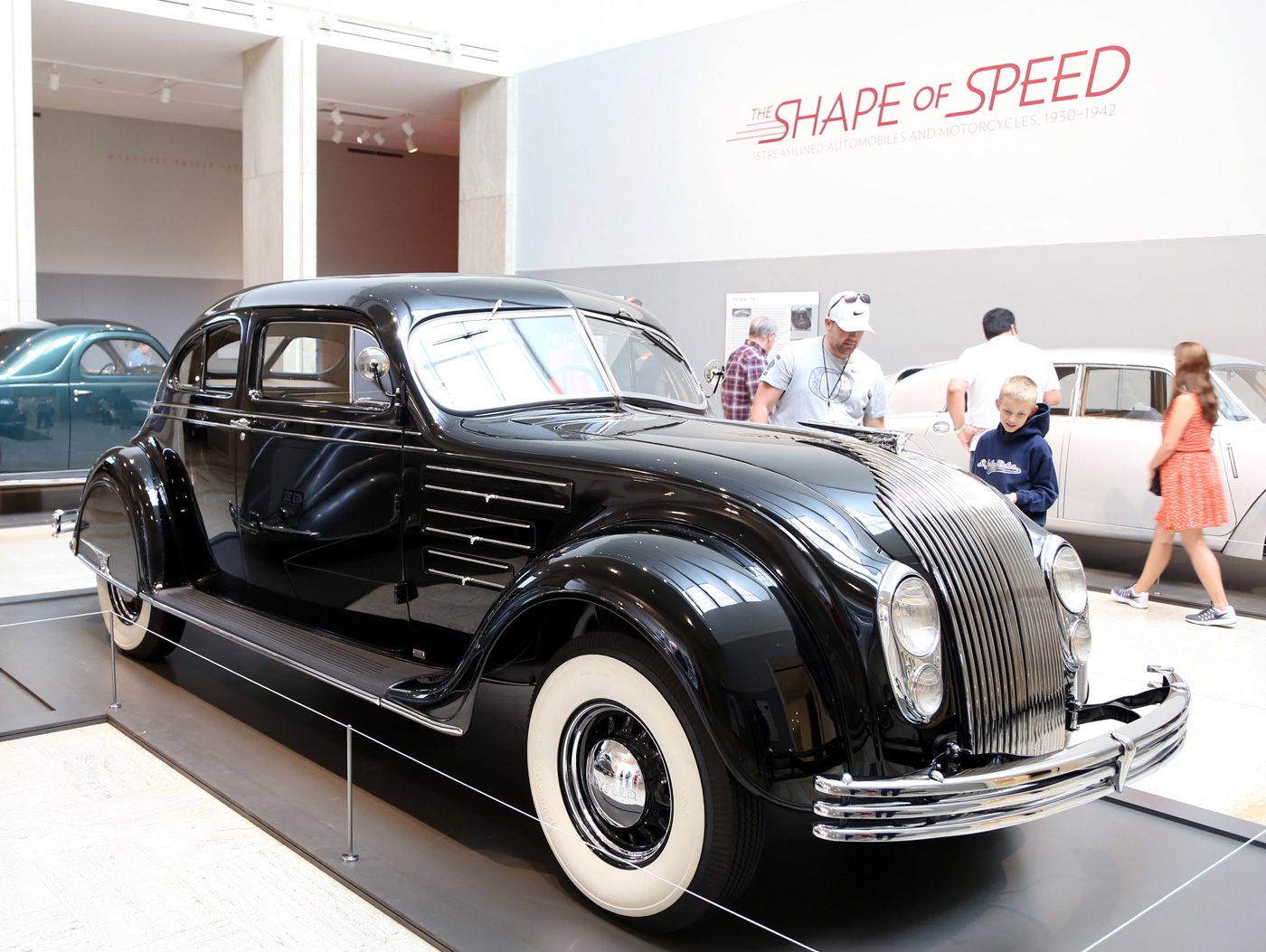

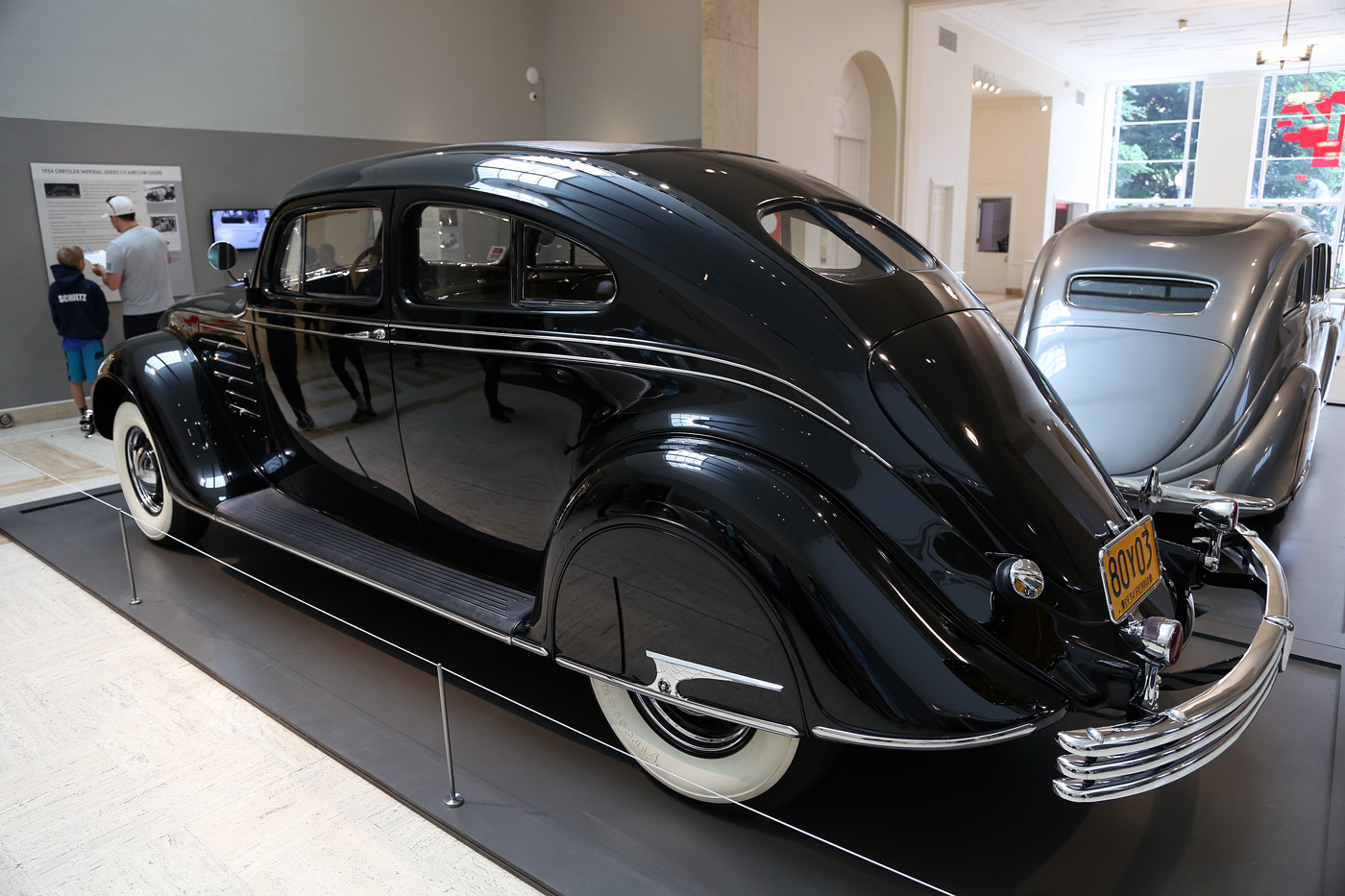

1934 CHRYSLER IMPERIAL MODEL CV AIRFLOW COUPE

Although the new Airflow was miles ahead in safety and strength, its unconventional design was also miles ahead of public acceptance. Sales figures were disappointing. A 1935 facelift included an extended hood with a vee-shaped prow. The new nose treatment was more marketable to the car-buying public. The bumpers were simplified and now evidenced a subtle expression of Art Deco influences. Chrome accents were thoughtfully employed and the overall appearance was less radical. Owners of 1934 models could order the new body components to have their older Airflows updated. From Shape of Speed catalog.

1937 AIROMOBILE

American Paul M. Lewis planned an affordable, lightweight, aerodynamic, and distinctive-looking car of the future, circa 1934. To bring his dream car to life, Lewis enlisted some serious help. The first Airomobile renderings were done by John Tjaarda, a brilliant designer at Briggs Body Company, whose streamlined, four-door, rear-engine Sterkenburg concept car was later adapted by E.T. “Bob” Gregorie to become the 1936 Lincoln-Zephyr. The Airomobile’s independent front suspension was composed of tubular shock absorbers, coil springs and control arms. The odd car’s single rear wheel, which was smaller than the two front wheels, was supported by a longitudinal, semi-elliptic leaf spring, a lone trailing arm, and a single hydraulic shock absorber. From Shape of Speed catalog.

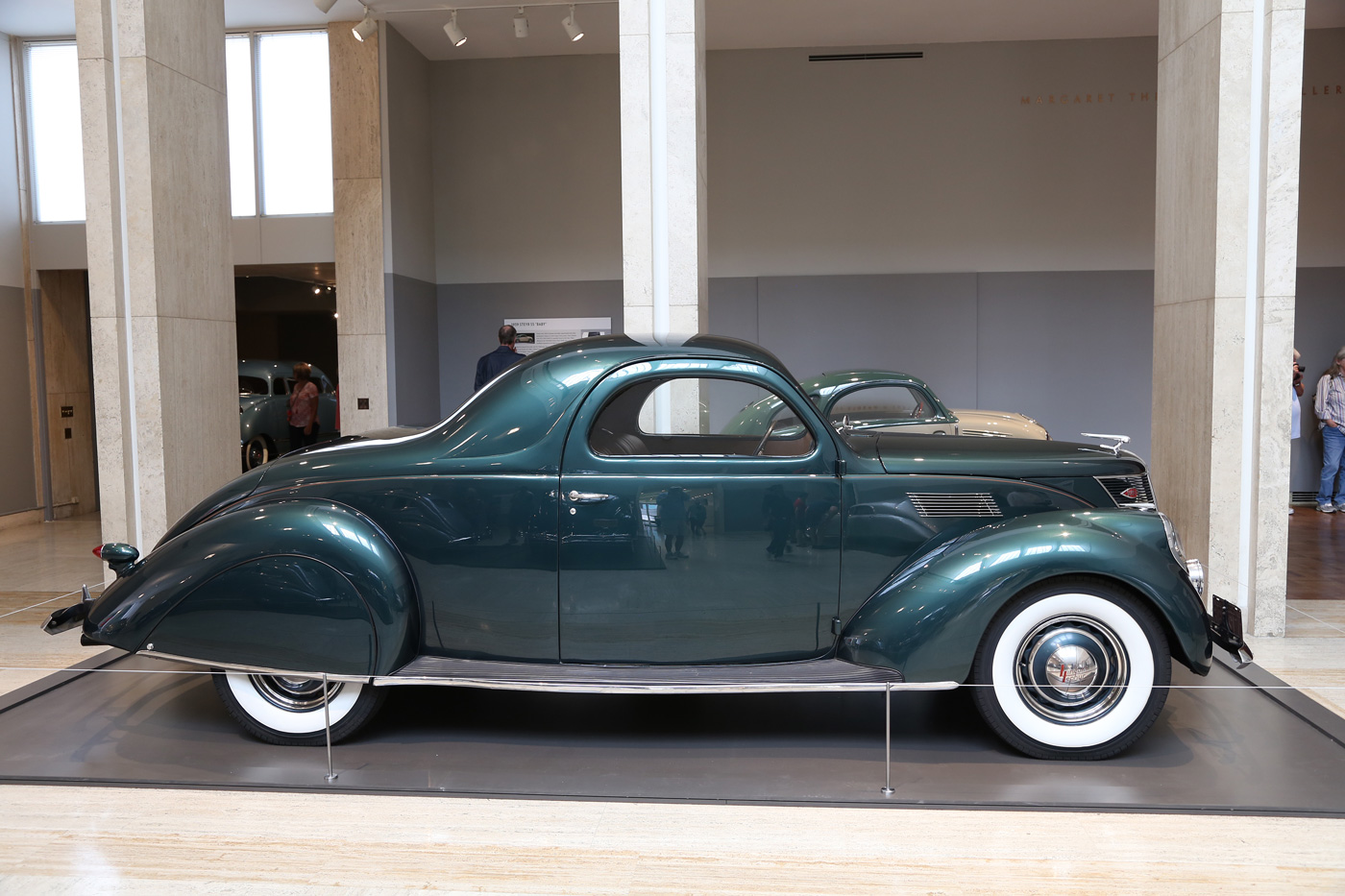

1937 LINCOLN-ZEPHYR COUPE

Although John Tjaarda might never have imagined it, the Lincoln-Zephyr, spawned by his futuristic, experimental Sterkenburg sedan, eventually sold more than 180,000 units, finally ending production in 1942. Arthur Drexler, Curator of Architecture at The Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and curator of the critically acclaimed 1951 MoMA exhibition, “8 Automobiles,” called the Lincoln-Zephyr, “the first successful streamline car in America. From Shape of Speed catalog.

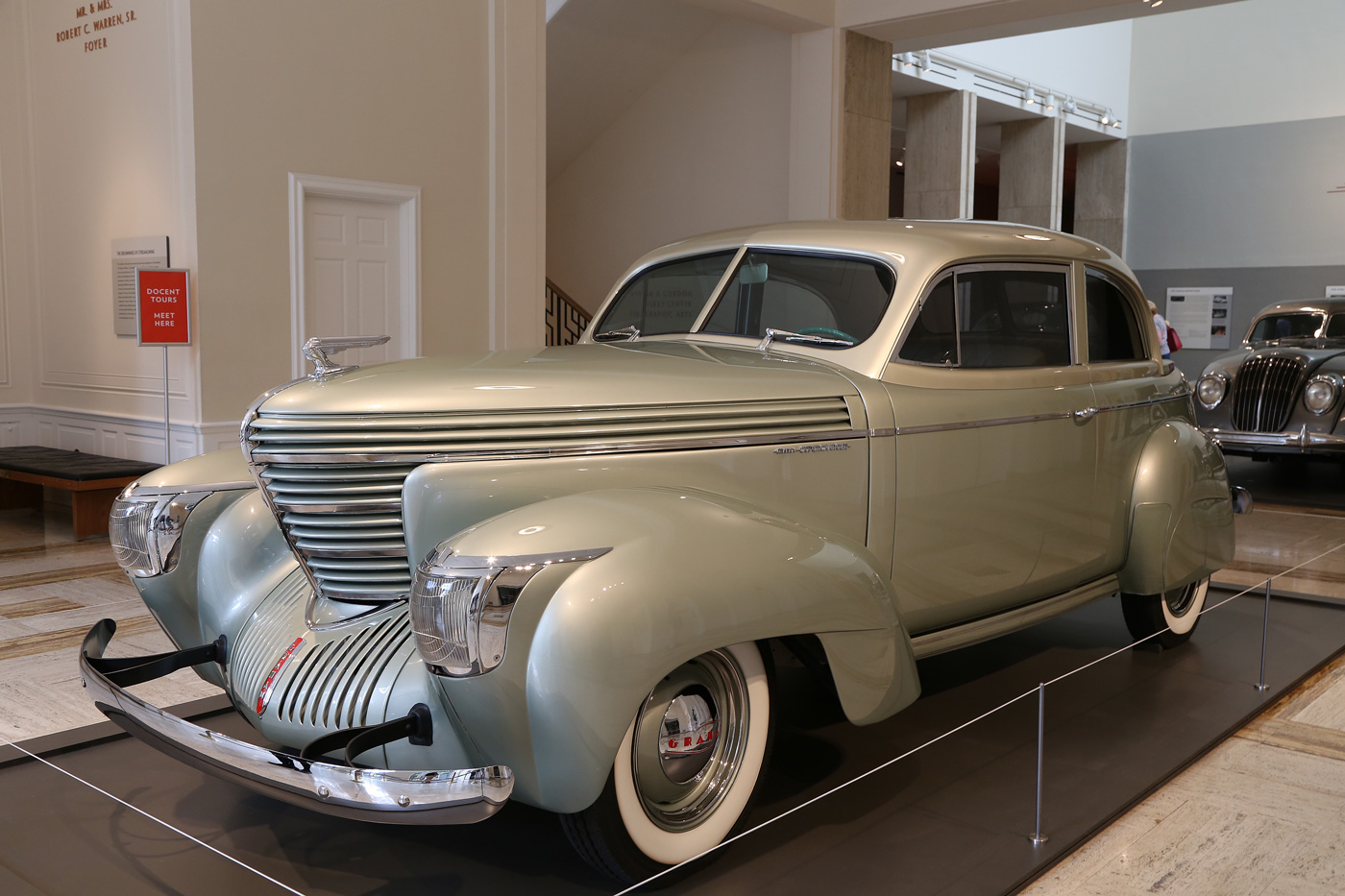

1934 GRAHAM COMBINATION COUPE

Popularly called the “Sharknose Graham,” this eye-catching design was the work of Amos E. Northup, whose styling details on the daring Sharknose still attract the discerning eye. The windshield and side window glass are large and airy. The Spirit of Motion’s massive headlights are Art Deco-inspired, with elaborately scribed lenses and a square-ish shape that must have encouraged considerable comment in the day. From Shape of Speed catalog.

1935 HOFFMAN X-8

Roscoe C. “Rod” Hoffman was an inventor and engineering contractor in Detroit who specialized in chassis and suspension design. A 1911 Purdue University graduate engineer, who’d worked for Haynes and Pierce-Arrow, he started his own company, Hoffman Motor Developments, in 1934. The Hoffman X-8 rides on a 115-inch wheelbase and weighs about 3,100 lbs. The rear suspension, quite advanced for an American car of that era, features fully independent half-shafts with Cardan universal joints at each end, along with longitudinal leaf springs and trailing arms. The brakes are four-wheel hydraulic drums. From Shape of Speed catalog.

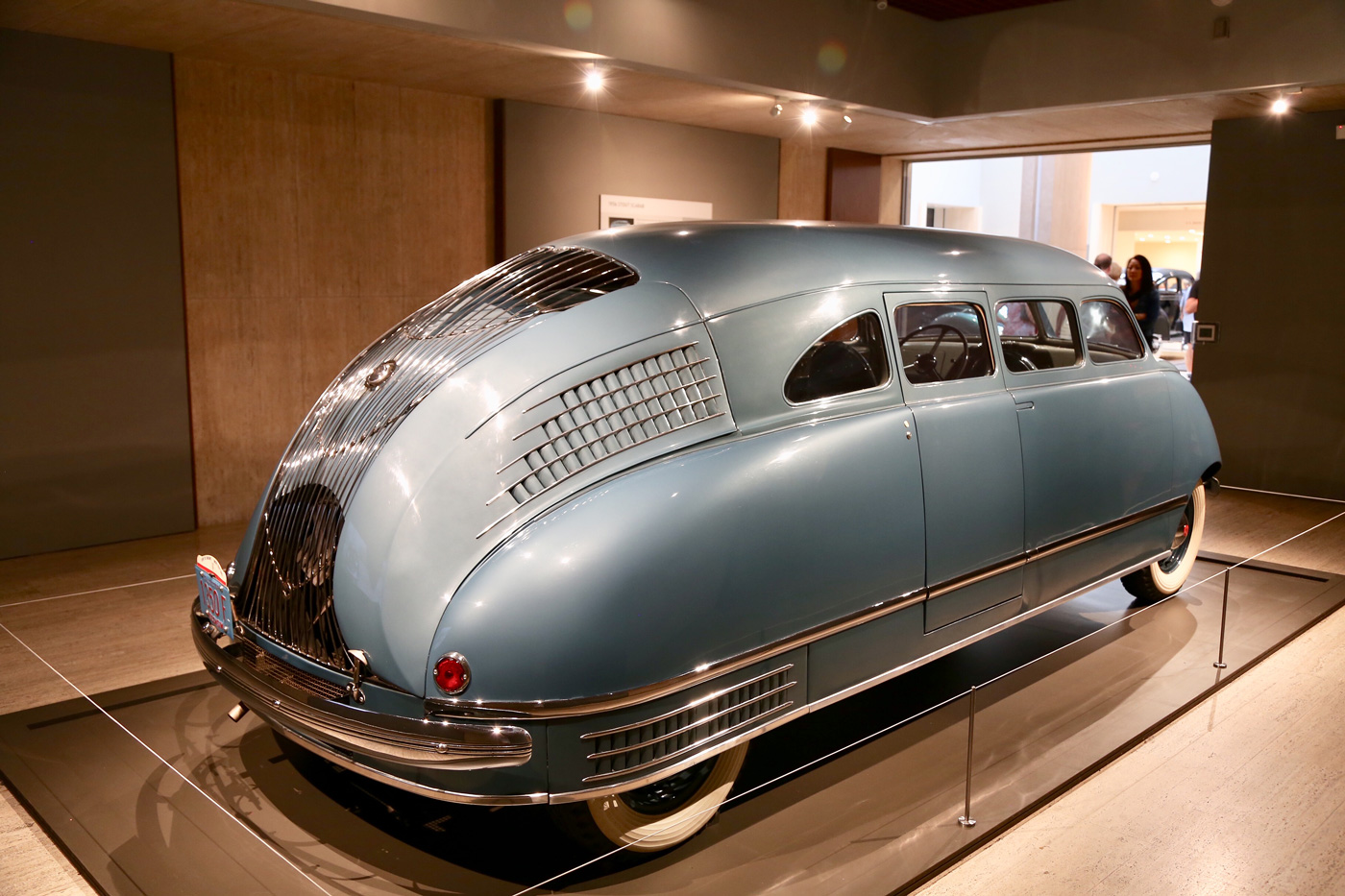

1936 STOUT SCARAB

William Bushnell Stout began creating a radical sedan concept in the early 1930s. Drawing on his extensive aeronautical background, Stout believed the use of aircraft construction techniques would result in a futuristic car that would go faster and be more economical than a conventional auto. He envisioned a smooth, slightly tapered, and, for its era, startling shape. A tubular frame covered with aluminum panels surrounded the Scarab’s rear-mounted, flathead V-8 engine. The Scarab’s distinctive turtle-shell styling celebrated its Art Deco influence, beginning with decorative “mustaches” below the split windshield, including the unusual-shaped headlamps covered with thin grilles, and culminating in fanshaped vertical fluting that framed elegant cooling grilles. From Shape of Speed catalog.

1941 CHRYSLER THUNDERBOLT

Chrysler confidently touted the 1941 concept car, the Thunderbolt, as “The Car of the Future.” Sporting a smooth, aerodynamic body shell, hidden headlights, enclosed wheels, and a retractable, one-piece metal hardtop (an American first), the roadster was devoid of superfluous ornamentation, with the exception of a single, jagged lightning bolt on each door. It stood apart from everything else on the road, hinting that tomorrow’s Chryslers would leave their angular, upright, and more prosaic rivals in the dust. From Shape of Speed catalog.

The Portland Art Museum is pleased to announce The Shape of Speed: Streamlined Automobiles and Motorcycles, 1930–1942, a special exhibition debuting at the Museum in Summer 2018. Featuring 17 rare streamlined automobiles and motorcycles, The Shape of Speed will be on view through September 16, 2018.

Our Senior Editor’s four part series on aerodynamic and concept cars can be found by clicking the below:

Read Part 1

Read Part 2

Read Part 3

Read Part 4

Great group of Dream Automobile! Jaime I