In this archived article, Peter LeSaffre discusses driving the ex-Musy Maserati 300S back in the good days of the Ferrari Shell Historics.

By Pete Vack

Color photos by Richard Prince Photography

In his epic book, Maserati 300S, Walter Bäumer tells us a fascinating story about a little-known race driver by the name of Benoit Musy.

He was the son of a President of Switzerland and “a brave man, who saved the lives of many German Jews in the last months of WWII.” Musy purchased a Maserati 300S, chassis 3057 new from the factory in June of 1955. He bought a truck to haul the car, his beautiful wife Consuela and young son Edouard. In 1955 and 1956, he entered seventeen events throughout Europe, winning six outright. But at Montlhléry in late 1956, Musy entered a Maserati 200S Maserati as the 300S was being overhauled. Tragically, Musy was killed driving the 200S, and his grief stricken wife sold the 300S immediately.

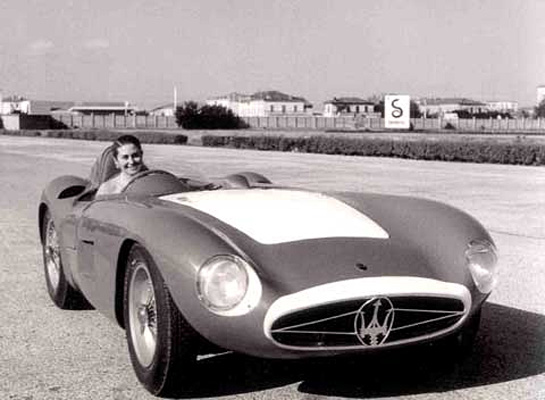

Consuela Musy sits behind the wheel of her husband’s new Maserati 300S. Together with their son Edouard, they traveled from race to race. Courtesy Walter Bäumer from the book 'Maserati 300S'.

After a long, hard life in Africa 3057 was discovered in 1987 by Swede Stein Johnson, who was tipped off about an “Italian beach buggy”. After its restoration, the car was sold to Michael Hinderer. In the meantime Musy’s son Edouard heard of the car’s existence, and was invited to ride in the car at the Nurburgring in 2001. For Musy it brought back many memories. “I still smell the oil and remember the sound,” he said. “Everything is there–again!”

Since then, the car was sold to the American vintage racer driver, Peter LeSaffre, who retained the distinctive white hood of the Musy ownership.

LeSaffre has also owned an A6GCS, a 200SI and is part of the select group of drivers who participate in the Shell Ferrari Historics. These are guys who have excelled in their fields in business and are quick learners and hard drivers. Unlike some historic events, the Ferrari Shell Historic Challenge is fully competitive and not a parade. Drivers must be the owners, and must have a competition license. It’s a group of highly competitive guys and everyone wants to win. “All the drivers in the series are pretty good, and we all have a great appreciation for the Alfas, Maseratis and Ferraris we race,” said LeSaffre. As can be expected, there’s a good deal of camaraderie. During an event, members of the group will meet for cocktails and dinner. “We talk about the field of cars running, the track, and of course the vintage car market. Never into the wee hours, though, because everyone is usually pretty beat from a day of manhandling their cars around the track.”

The LeSaffre 300S retains the white hood that was a color combination used by both the factory and Musy.

The three Maseratis owned by LeSaffre spanned the great postwar era and each is a valuable historical object. Racing these cars poses problems of sorts. Having an accident in such a car is akin to accidentally putting one’s hand through a Van Gogh. It takes a certain amount of moral certitude to subject an art object to the extremes of vintage racing, no matter how much money one is worth. Le Saffre has been competing against the same drivers over a period of six years. “You get to know the driving skills and traits of the other drivers,” he says. “Not knowing who you are going into a corner with can be unnerving.” This elite group believes that it is the car’s destiny to be raced and that is what it is all about, and all other considerations fall quickly to the wayside.

LeSaffre has the money to repair any damage done along the way, but in the final analysis, once the clutch is engaged, the rear wheels are smoking, one has to ignore the downside. “Just keep thinking, every car can be fixed”. Once, a car owned by a friend of LeSaffre’s broke down in the disc brake group. “I offered my drum brake car to drive, at first he was reluctant, but I convinced him that if anything broke it can be fixed. Well, he flipped it on the 3rd lap, race was black flagged. He was pretty shaken up, but far more upset about my car.” The two are still friends. LeSaffre says the Historic Series has only three real incidents over an 11 year period.

People who see LeSaffre race often come up to him and ask a few questions, but most ask the traditional “whottle she do down the straight?” But the straights are easy, whether consumed at 100 or 150 mph. “Many people don’t realize the fact that although these cars were top notch in their time, brakes are almost non- existent, handling is truly marginal, and yet they often have the power and torque of a modern.” says LeSaffre. “You get used to the speed down the straight. The real action begins when you start your braking and turn in, trying to find the perfect balance between entry speed, braking just enough to scrub off the right amount of speed and at the same time, trying to keep enough adhesion to make it around the corner. This is when you need laser like focus, tremendous concentration, anticipation and that famous old seat of the pants feel for what the car is telling you. It’s mentally challenging, and pretty physical in 1950 era sports cars.”

Back in the pits, the mechanics have to deal with potential breakdowns. LeSaffre’s mechanics do their best to show up at every race with “the hood down”. But under racing conditions, if there’s a weak spot, it will show up on the track on race weekend. Trailers are loaded with as many spares as possible with a full line up of tools. “I really think the mechanics play a crucial role in keeping your car safe and running properly over a long weekend,” says LeSaffre. “They definitely want to win, as much as the driver, and put a lot into what they do and have a great deal of pride.” At the first race of the season at Moroso LeSaffre’s trans-axle lost 4th gear. “My guys Fed-Xed a spare from the shop overnight, removed the gearbox and had the car up and running by 2 pm for a few test laps before Fridays qualifying!” As a result he was able to qualify and win the first race of the season. “You just don’t do that without a great crew, certainly not alone.”

they travelled from race to race but this photo was taken at the circuit of Modena