Story by Paul Wilson

Photos by Jonathan Sharp unless otherwise noted

When they were built, the ancient vehicles puffing and creaking their way every year from London to Brighton were called “horseless carriages.” Yet in an astonishingly short period–only really from 1899 through 1904–the most advanced cars outgrew the term, with dramatic functional and aesthetic development that erased their horse-drawn origins. Because the cars depart from Hyde Park in chronological order, earliest first, an amazing history lesson unfolds before us. But to understand it fully, we need to reconsider what “horseless” meant, to someone early in the last century.

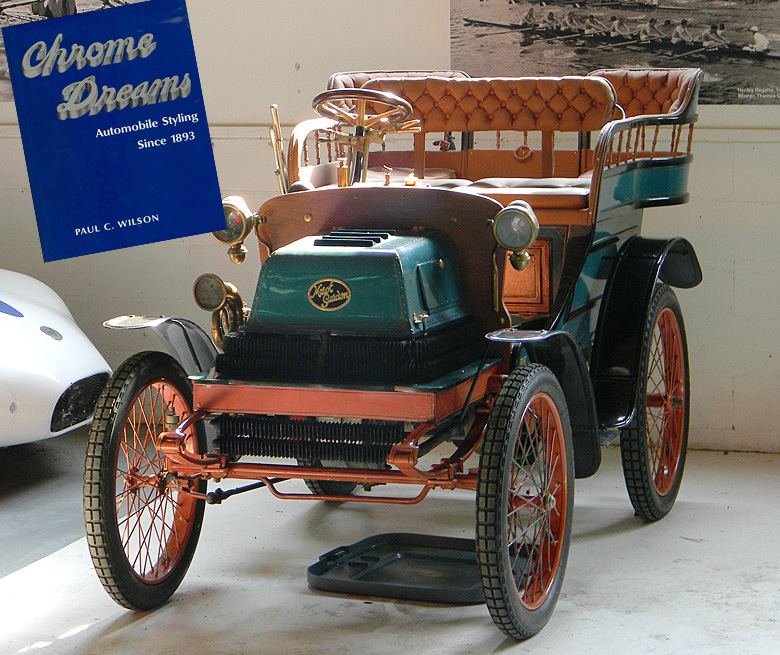

Dispense with the horse and you have the first motor vehicles. But that would change very quickly. Photo Courtesy PW

The earliest cars were simply carriages minus the horse. To see over the horse, the driver had to sit high. The wheelbase was short for best maneuverability; the carriage needed no directional stability on its own, because the horse provided it through the shafts and harness. A light carriage was a fast one, so it should look and be light. Speeds were limited, so while carriages often overturned, lateral stability was a low priority. The horse was obviously the motive power, and the dynamic excitement of the ensemble depended on its power and grace. The carriage passively rolled behind.

One of the few pre-1899 cars starting last year was this 1898 Bergmann. With solid tires on tall wheels, patent-leather fenders, driver perched high on a light carriage body, it differs from the horse-drawn vehicle shown above only through having growling, exposed mechanicals whirring underneath. The 1899 Peugeot also has what contemporaries called a “horse-wanted look.” It would look fine with a four-in-hand prancing along ahead of it, but without the horses, something essential was missing.

Small cars developed along a different track from the big ones, so we’ll look at them first. The fastest things on the roads of the 1890s were the Count de Dion’s motor tricycles, and every Brighton run sees many strange mutations, halfway between a motorcycle and a car. Three-wheelers from Marot-Gardon, de Dion Bouton, and Leon Bollee, all from 1898, held this year’s starting positions from #7 to #10, ahead of some four hundred later cars.

If you are enjoying this article please click here to subscribe to VeloceToday for only $5 a month!

Most people preferred a four-wheeler, however. An early example of what would become a standard type of small car is the 1899 Star. Lower than the big carriages, it has slightly thicker tires, though maybe not yet pneumatics. Except for the drive chains, the mechanical parts are concealed. Most early American cars followed its basic plan, a runabout with its engine in a box below and behind the seat.

The 1903 curved-dash Olds represents a refined version of this concept. No higher than necessary, with a stretched wheelbase and equal-sized, large-section pneumatic tires on both ends, it was well-suited for American conditions–light, handy, tough enough to navigate the nasty mud tracks that most American roads were at the time.

Even in France, where big cars were quickly evolving into an altogether different and ultimately superior form, de Dion Bouton’s light runabout was the world’s best-selling car at the dawn of the new century. Reliable and strong, dozens of these drive to Brighton every year. Their body style was called vis-a-vis (“face to face”), because the front passengers faced backwards towards the rear-seated driver. The cars were popular, but not the seating position; later models didn’t use it.

Big cars evolved on a different track, one that leads back to a single ancestor, the Panhard-Levassor of 1891. Its système Panhard put the engine in front under a hood, driving the rear wheels through a sliding gear transmission. Without shafts reaching forward to the horse, a short-wheelbase vehicle was twitchy and unstable, especially with high seating. The Panhard’s layout ultimately solved these problems by allowing cars to be built longer and lower, a trend that accelerated after 1900. This 1901 Panhard displays another of the firm’s innovations, a steering wheel, adopted after Emile Levassor was fatally thrown from his car by its queue de vache (cow’s tail) tiller in 1897. They were nearly universal on French cars by 1899.

A front engine under a hood had aesthetic advantages as well as practical ones. Without a horse, early cars had no visible power source. People felt uneasy about the “magic carpet look” of light runabouts like the Curved Dash Olds. So when the système Panhard took hold, they immediately recognized the front hood as the engine location, the symbolic substitute for the horse. No more “horse-wanted look”; cars now looked complete and logical by themselves. Suddenly, in about 1901, everyone wanted a car with a front hood. Usually they looked like this one on a 1902 Delahaye, with decorative brass corner panels and a radiator slung below the frame in front.

From 1901, Renaults had a similar hood shape, but they experimented with different radiator locations. This 1903 Renault has radiators on the hood sides, like their Paris-Madrid race cars. With a long hood, a long wheelbase, strong artillery wheels of equal size on both ends, this car has proportions that were unthinkable just two years earlier.

In 1901, Mercedes introduced the last feature that would be standard on cars for the next several decades: a shaped radiator that formed the front of the hood. Its honeycomb construction presented a smooth face, and the radiator sides were brass. Functional and handsome, it was immediately copied, and hardly a single car built in the decades after 1904 (the Brighton Run cutoff date) did not have a Mercedes-look hood and radiator. When the 40-horsepower Mercedes was introduced in 1901, The Horseless Age commented that “The most striking feature about the Mercedes is undoubtedly its lowness of build, and it is safe to say that for the average American road the limit in this direction has been reached in this vehicle.” Equal-sized front and rear tires on this 1902 Mercedes make it look even more modern.

Ironically, the extraordinary achievement of these early Mercedes makes them uniquely hard for us to appreciate. Car design advanced so fast that most cars of this era soon seemed old-fashioned and had sub-standard performance. They became “old crocks,” seen as endearingly odd, just as we see them. Not the Mercedes. In fact, they were copied so closely, in their size, proportions, and general appearance, by so many other makes in the next few years, that virtual copies were soon available from premium car builders on both sides of the Atlantic. Here, for example, is an American-made 1906 Locomobile.

And compared to the early cars, the clones were built in large numbers, so any big museum or show will have something that looks similar. A phrase once used in a Cadillac ad, “The Penalty of Leadership,” applies exactly to these remarkable Mercedes.

Parading past you is a dramatic story of quick technical and aesthetic development. The more you know, the more you’ll enjoy it.

This year when you see pictures of the Brighton Run (or if you’re lucky, you see the event itself), give yourself a quiz: can you guess the year each car was made? Of course, progress was not constant and uniform, and American cars were on a separate track. But development was so rapid, and especially in Europe, ideas spread so quickly, that you should be able to come close. Is the car very high and short? Does it steer with a tiller or a wheel? Where is the engine? Does it have a hood? How long is the wheelbase? What size are the wheels? Equal on both ends? Do they look frail or strong? Does the radiator form the hood front? Parading past you is a dramatic story of quick technical and aesthetic development. The more you know, the more you’ll enjoy it.

Paul Wilson not only owns a Lamborghini Miura, but at the other end of the scale, a rare Marot-Gardon. In his book “Chrome Dreams” Wilson deftly describes the rapid – and interesting changes in the automobile between 1899 and 1094. We asked him to do the same using Jonathan Sharp’s images from the 2016 Brighton Run. Photo of Wilson’s Marot-Gardon by the Editor.

Pete,

That was a great article. It would be great to run an article on the Times-Herald trials and contest. My Great Uncle, Dr. Carlos Booth had a car built in the Youngstown carriage shop but it wasn’t ready for the contest. He was noted as the first Doctor use a car to call on his patients. But was ordered off the streets for scaring the horses. My aunt related many stories of the problems encountered. It would be great if we could get-together get some of the recorded.

Hi Frank Shaffer,

50 years ago I got started on a book about the really early cars, based on my reading of all The Horseless Age from 1895 on, and one of my sections (not a full chapter) was on your great-uncle! I’ll see if I’ve still got that stuff. There were lots of great stories, lots of insight into the circumstances of introducing cars to replace horses. My best source was the annual Doctor’s Issue of HA, where doctors compared the cost of the car vs. the horse, for their country practice. Alas, I found that nobody wanted to publish such a book, because virtually nobody wanted to read it. I had to make a living, so I moved on to A Real Job.