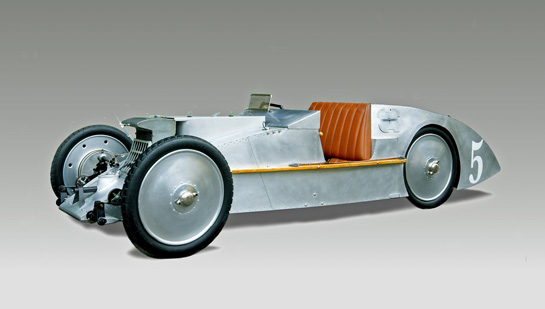

Notice: Moch’s striking aluminum ‘Laboratoire’ will be one of the highlights of a special exhibition dedicated to Gabriel Voisin, that will run from November 10, 2012, for six months at the Mullin Museum in Oxnard, California.For more information see: http://www.mullinautomotivemuseum.com/

The rebirth of a 1923 Voisin ‘Laboratoire’ was inspired by a book.

What moves man to recreate a masterpiece that someone else has already created a long time ago? In the world of music this is quite common. We all love to listen to concerts in which conductors and orchestras recreate the music from scores that were penned down by famous composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Sibelius or Leonard Bernstein, to name a few.

In films and theaters we applaud when directors and actors recreate the scenes and words originally fashioned by writers such as Jane Austen, Samuel Beckett, Arthur Miller, Oscar Wilde, Tennessee Williams or William Shakespeare.

Art students visit museums to find out how the old masters did it. Some of them then painstakingly recreate composition, lights and shadows, and sometimes colors and even brushstrokes. There’s nothing wrong with any of this…it is taken for granted.

However, in the world of visual arts, recreating is generally frowned upon by professionals. Not only because criminals have offered forgeries to unsuspecting buyers as being the original work of the well-known painters. Copying, or even painting in the style of an old master, is regarded as a lack of creativity and artistic imagination.

Then what about recreating mechanical masterpieces, such as automobiles of historic significance, originally created by engineering genius like Ettore Bugatti or Gabriel Voisin? Let’s find out from Monsieur Philipp Moch, who in 1993 recreated a Voisin C6 Course or ‘Laboratoire’, the revolutionary racing machine that participated the 1923 Grand Prix de Touraine.

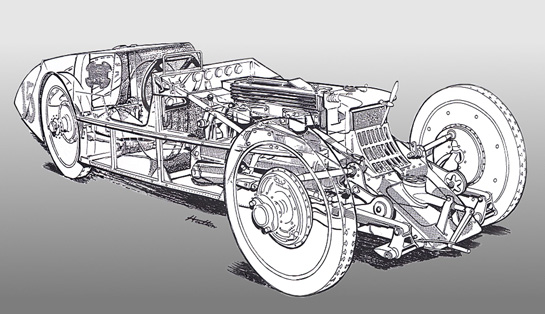

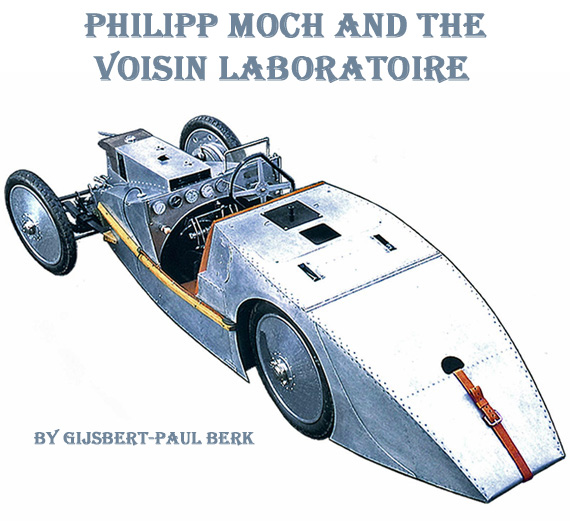

As the original drawings had all disappeared, Moch needed to reconstruct the ‘Laboratoire’ by using photos that were taken in 1923 of Lefebvre and Duray at Semblançay. As shown in this cutaway, that would be no easy task.

At first contact Monsieur Moch (now in his early 60s) seems an unassuming and slightly timid person. But this first impression is misleading, because he is a man with a strong drive and great passions as well.

He originally wanted to become a professional pilot and fly fast aircraft, but instead he became a motorcycle racing hero. He has 31 National French motorcycling and sidecar championships to his name. In 1975, Moch designed a machine with two Kawasaki engines to challenge the American Don Vesco. Vesco had just established the international speed record for motorcycles in his Silver Bird, equipped with two Yamaha TZ750 (1 480 cm3) engines, at Bonneville at over 487.515 km/h (302.92 mph). However, Moch never realized that ambition for lack of time and money.

Instead, having gained a lot of practical experience working with strong and light constructions of fiber-reinforced plastics or GRP and aramids such as Kevlar for his bikes and sidecars, in 1976 he founded a company specializing in making components for the aviation industry. His reputation grew and in 1984 he was asked to produce the carbon fiber monocoque chassis for the Renault Formula 1 cars. While orders from his aeronautic clients increased (his company also made the interiors for the Concorde), Moch also became more and more involved in the development of prototypes for the auto industry. Among them the 1989 Matra M2, the 1995 Espace Renault with the 850cv V10, the 1999 Clio V6 show car, the F1 Ligier and several others.

Instead, having gained a lot of practical experience working with strong and light constructions of fiber-reinforced plastics or GRP and aramids such as Kevlar for his bikes and sidecars, in 1976 he founded a company specializing in making components for the aviation industry. His reputation grew and in 1984 he was asked to produce the carbon fiber monocoque chassis for the Renault Formula 1 cars. While orders from his aeronautic clients increased (his company also made the interiors for the Concorde), Moch also became more and more involved in the development of prototypes for the auto industry. Among them the 1989 Matra M2, the 1995 Espace Renault with the 850cv V10, the 1999 Clio V6 show car, the F1 Ligier and several others.

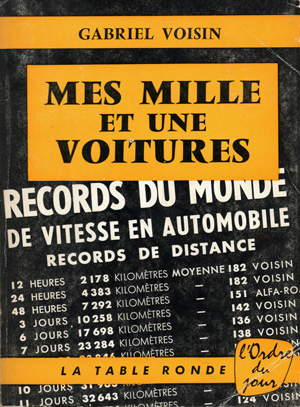

His interest in and passion for Gabriel Voisin’s eccentric creations more or less happened by chance. Shortly after he received an offer to sell his successful enterprise, a friend lent him a book written by Gabriel Voisin, one of the French aviation pioneers. During World War I, his factory at Issy-les-Moulineaux (now the site of a Heliport) produced some 10,000 aircraft for the Allied forces. After the Armistice in 1918 he switched his efforts to manufacturing cars. Voisin was also a proficient writer. Not only did he write several books but also his own sales brochures.

The book Moch read was Voisin’s autobiography Mes 1001 Voitures (recently translated into English and published by Faustroll Books, SBN: 978-0-9569811-2-7). In this book Voisin recounted his life in the period between 1917 to the sixties.

With humor and hindsight Voisin described his transition from an aircraft designer and manufacturer to a manufacturer of cars He wrote not only about his successes and disappointments, but also revealed much about his engineering philosophy and his personal (love) life.

Probably because Moch himself was contemplating a big change in his professional life, the book had a great impact. It awakened his interest in the machines produced by Voisin who was at the time, a practically unknown and forgotten automaker. By Moch’s own admission, he was always fascinated by engineers who designed both planes and cars.

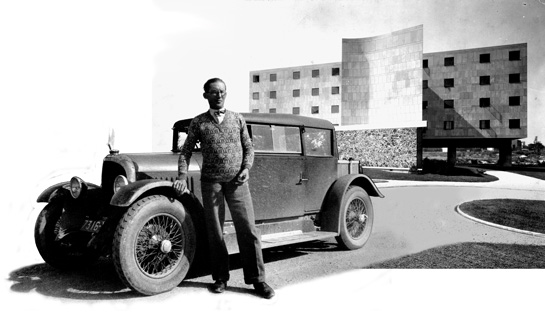

French architect Le Corbusier posing with his Voisin ‘Lumineuse’. In the background one of his remarkable buildings.

So he started collecting. One of his first cars was a Voisins C23 ‘Lumineuse’, a model that gained much popularity around 1930, and not only because the famous French architect Le Corbusier published photographs of his own ‘Lumineuse’ in front of his revolutionary projects such as the Villa Savoye near Poissy and the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille.

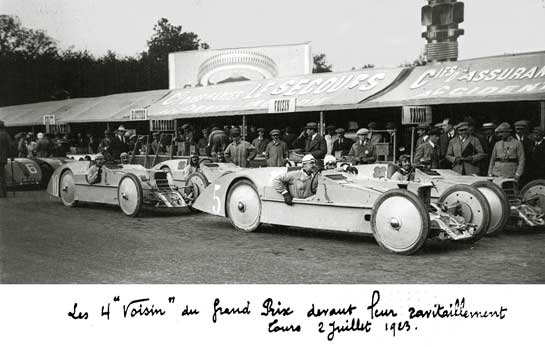

Moch also was close to purchasing a Bugatti Type 35, but he could not agree with the vendor about the value—much more expensive than any Voison– and the sale fell through. Plus, over time Moch had acquired a great number of Voisin spare parts. It was then that Moch decided to recreate a unique Grand Prix car himself. His choice was clear: the famous and controversial C6 Course or ‘Laboratoire’, developed by Voisin and his top engineers André Lefebre and Marius Bernard for the 1923 Grand Prix de France.

There was, however, one small problem. There were no surviving examples of this fascinating mixture of aviation technology and avant-garde racing car design. Not only had all the cars that participated at Tours and Monza been destroyed or scrapped, the original drawings had also disappeared. Thus Moch needed to start from scratch. With the help of contemporary photographs, press reports and personal notes of Gabriel Voisin (who had passed away in December, 1973) he and a few collaborators managed to reconstruct the dimensions and construction details of the car. They produced over 100 m2 of plans and drawings.

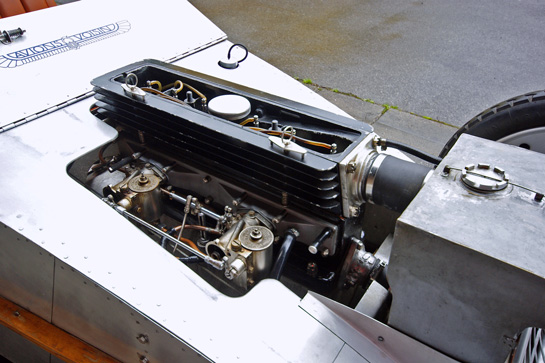

Then came the task of sourcing the correct mechanical parts. In 1923, Gabriel Voisin and his team used as many components as possible from the parts bins of passenger cars they produced at the time, because they had to complete the Grand Prix cars in barely 6 months’ time. This of course helped Moch, as he could do the same. The power plant in his car is an original Voisin sleeve valve six cylinder from a 1926 C 11. This engine was in fact derived from the 1.993 liter prototype that Marius Bernard designed for the 1923 racer. It has the same stroke of 110 mm but the bore was enlarged from 62 mm to 67 mm resulting in a cubic capacity of 2.326 liters. There are two Zenith carburetors as fitted on the Tours cars. However, it has dry sump lubrication to reduce the oil temperature and prevent the excessive ‘smoking’ of the Tours cars.

To construct his recreation Moch used the same tools and equipment that were available in 1923, when the original Voisin C 6 Grand Prix racers were made. Photo Philipp Moch.

The front axle, rear axle and the steering had to be custom-made using a maximum of original Voisin components. For the narrow 765 x 105 tires, Moch recruited the help of Michelin. The aluminum monocoque body, strengthened with wood spruce, was entirely constructed with tools and equipment that were available in 1923. “We did not use modern techniques or computer-aided production methods, as we wanted a result that was totally identical to the original”, declared Moch. Including 10,000 hours for the plans and drawings, he estimates that the recreation took them a total of about 13,000 hours.

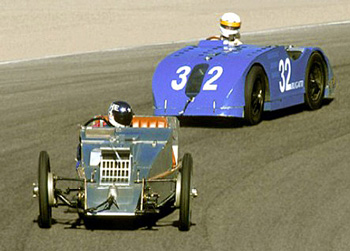

Philipp Moch and Bob Sutherland dueling with their replica Voisin and Bugatti on the Laguna Seca race track in 1995.

Details of the Voisin Laboratoire Recreation. All photos below by Hans de Wit.

The front track measured 145 cm, the rear track only 75 cm, and the wheelbase 272 cm. This is a frontal view of Moch’s machine.

Moch used an original 2.3 liter 6 cylinder Voisin engine for his recreation. It is virtually the same as the 2-liter prototype Marius Bernard designed for the 1923 race but has a slightly larger bore (but the same stroke). Like the original, it is fitted with two large Zenith carburetors.

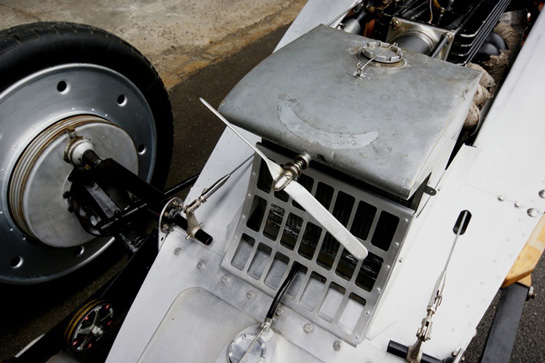

The small propeller in front of the radiator served to drive the water pump, in this way economizing a bit of the limited power of the sleeve-valve engine.

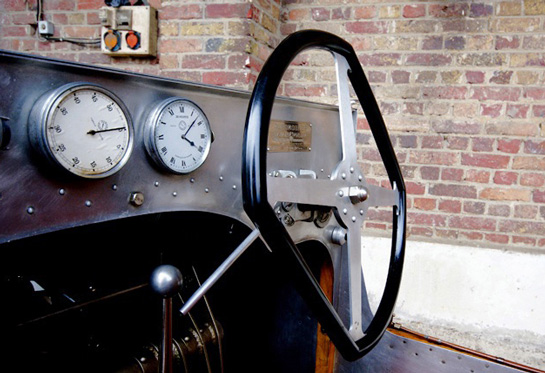

The cockpit is purely functional and reminds one of that of an aircraft. Note the gear change lever. The open cables on the balance axle, operated by the brake pedal, connect directly to the rear wheel brakes.

The original Tours racers even had a clock on the dashboard; Moch’s recreation has also been fitted with one. Note the square steering wheel. Some Laboratoires had them, but not all. Lefebvre’s car was equipped with a normal round steering wheel.

View of the left front suspension with its leaf spring and friction damper. The wooden strip at the top of the photo served to strengthen the thin aluminum body panels and gave also some side protection.

The racing screen in front of the driver was not made from glass but from mosquito mesh. It could be folded down.

The shining aluminum wheel discs were meant to reduce aerodynamic drag. They hid wire wheels with very narrow tires designed to keep the rolling resistance down. At Monza some of the Laboratoires raced without wheel discs.

In 1923 even Grand Prix cars carried spare tires. This photo shows how this fifth wheel was placed in the sloping tail.

The petrol tank was located directly behind the driver and his riding mechanic. To refuel this click-on panel had to be removed. During the race this proved to be impractical.

Note: In collaboration with the well-known French Auto Historian Serge Bellu, Philipp Moch has recently produced the book “Vitesse – Elegance” French Expression of Flight and Motion. It is about Gabriel Voisin’s achievements and published in English by Coachbuilt Press (ISBN: 9780977980918).

Mr. Voisin was a brilliant designer and builder. I very much look forward to visiting the Mullin Collection and seeing this machine first-hand. It is interesting to see the contrasts between this aerodynamic, reverse-teardrop racer and some of the Cubist sedans he produced.

I don’t think that I have ever been so intrigued by a car as I am by the Laboritoire. I was fortunate to see it in person at the Mullen but this article adds all sorts of dimension to the vehicle. It is fantastic.

I really like articles like this and the one about the Alpine, sometimes recreations are necessary to keep history alive.

I look forward to reading the books on Voisin and learning more about this visionary.

We saw this car at the Art Center Classic last month. AMAZING!

The English version of Voisin’s book, My 1001 Cars is available at Autobooks, http://www.autobooks-aerobooks.com/cgi/commerce.cgi?preadd=action&key=15889&title=MY-1001-CARS

as is Vitesse Elegance, http://www.autobooks-aerobooks.com/product/16145/Vitesse-Elegance–French-Expression-of-Flight-and-Motion/

Looking forward to t he new exhibit at the Mulllin.