This article originally appeared in VeloceToday on August 13, 2002.

By Ed McDonough

There are cars and there are cars.

I like to work on my personal list of the greatest/most desirable racing machines of all time, and then check off the ones I’ve driven. The list is at 72 out of a possible 100 and I have managed 20 so far, lucky person that I am—Ferrari 268SP, GTO, Jaguar C-Type—all with significant history.

The Lancia D50 would have been on the list, naturally, though I knew some time ago that it would never be driven. The two surviving machines reside quietly in the Lancia and Biscaretti Museums in Turin, and never run. However, I was towed around in one of them at the end of a rope, but that hardly counts.

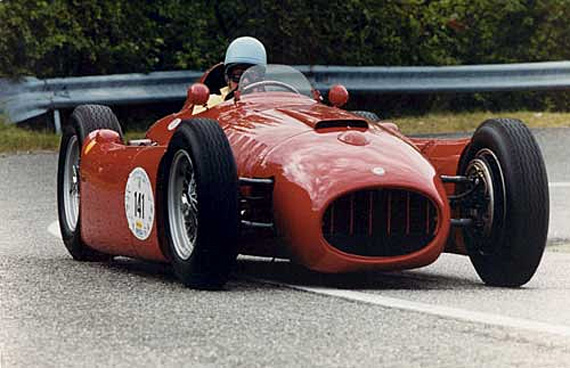

Then a few years ago, Guido Rosani, the son of a former Lancia employee, took one step further an idea he had nurtured since boyhood. Guido’s father had carefully ‘conserved’ many of the Lancia D50 engines, transaxles and other spares after that fateful July day in 1955 when all but two of the Lancia Grand Prix cars were shipped off to Enzo Ferrari as Gianni Lancia’s empire collapsed. Guido had thought ‘one day I will build the cars again’, and so, with the help of a British consortium, he did. The idea was to recreate four of the early D50s and two of the later cars with ‘merged’ bodywork extending over the wonderful fuel panniers which hung between the wheels. Orders for the cars were quick in coming.

The cars were sent to England to the workshops of Jim Stokes, who took them to pieces and rebuilt them with historic racing in mind. The original engines were used along with complete gearbox assemblies and other suspension parts. While arguments took place about the likelihood of the cars getting FIA papers, well known historic racer Robin Lodge ordered one, which duly arrived in April, 2000. Jim Stokes and later Tony Merrick both worked on sorting the car, particularly the handling. Robin Lodge said there was a point when the car would only need to see a corner to spin. He ran it in a number of events and the car, not surprisingly, had a fantastic welcome wherever it went. The arguments about originality became petty once people heard the sound of the very original engine, belting out a modest 260bhp from that lovely V-8.

Having established a rapport with the good Mr. Lodge, I made agreement that I would get a track test in it in the future. That finally came about in April this year at Silverstone, where the Historic Grand Prix Cars Association was holding a test day. Robin said that the handling had been improved by putting in softer springs. In fact, the ones already in use had no movement in them at all.

Having contemplated the reality of being the first journalist to do a track test in a D50, I got down to the task in hand. (As it happens, that claim is questionable- one period journalist drove one from the garage at Monaco in 1955, Paul Frere raced one but didn’t write about it, and Brit Willie Green tested this car but didn’t really do a ‘track test’!) All other claims are untrue!

At Silverstone, the car was impressive in the way it delivered power to the ground with great smoothness, superb torque, the gearbox was fluid and exact with no problems at all, and whatever handling gremlins there had been were gone. It was a stunning experience, running in traffic with 246 Dinos, Maserati 250Fs and similar period wonders. The sound was fantastic Italian tuba playing, ebullient and tonal, just a joy to drive.

Shortly afterwards, Robin asked if I cared to share the car with him for some runs in the Silver Flag Hillclimb near Piacenza in Italy. Drive the D50 in Italy? I knew I would wake up soon.

The Silver Flag was a 1950s hillclimb from the village of Castell Arquato to Lugagnano to Vernasca, a total of ten kilometres. Resurrected a few years ago, the event now attracts wonderful Italian machines in June for two days of racing and eating. The first half, to Lugagnano, is virtually flat fast bends with no climbing, but a few cones to slow you down as you approach the village, ninety degree left past the bus stop, downhill out of town, and then 4.5 kilometers of steep climb and sixty (!) 2nd and 3rd gear corners. The crowds turned out for day two as Saturday had been rained off, but the D50 was ready to go, and so was I soon replicating the great Alberto Ascari in yellow shirt and blue helmet. It was Ascari ‘s D50 which plunged into the harbor at Monaco in 1955, to be remembered forever.

The Lodge D50 blasted out from between the crowds that lined both sides of the public road. As I shifted up through the gearbox to top and 7000 rpm, the car was accompanied by the waving of 70 and 80 year old arms from the roadside—the Italian racing memory is long.

Into Vernasca in second, the car having been flawless through the quick part, the tail waggled as I turned hard left and aimed it downhill, over the bridge at 140 mph and towards the hill, playing the gearbox like a violin, listening to V8 sonatas as the over-square Lancia engine did its business, pulling the iconic racer up the hill. Because it behaves so well, you can think about it, you can take in what you are driving, and you can enjoy it. Second to third to second to third—a rhythm begins to develop…the tail just begins to go, but is always caught with the throttle. The brakes are fine but not that necessary–this is totally a car and a throttle—it all emanates from the right foot.

This is a bit of a cliché, but that was the dream realised. What next?

I watched an original D50 from the LANCIA Museum at the Classic Days around Schloss Dyck near Düsseldorf last August driven by a member of the Museum staff.

On a narrow road lined with trees this was an amazing appearance, and the Driver was kind of idling, as he said.

There is an impressing video featuring Fangio at the wheel of a D50 in Monaco which helps sharing the feeling, if not the talent.

What evocative writing. Lucky b….

Please, Mr McDonough, describe the car and how is to drive a D50. The rest you’ve been talking abaout just doesen’t matter. OK?

One of the most brilliant conceptual designs of all time.

Dear veloce

Anybody out there Old enough to remember when this fabulous car was on pole

position for its race debut,,?

I do and thought it stunning the reigning World Champion Alberto Ascari

had done so,,! (Spanish GP, October 1954)

Terrific shot of him at Monaco,thanks foe the memories

jim sitz

Oregon USA

I finally got to see a genuine D50 at the Enzo Ferrari Museum last year – a genuine “bucket list” event. My friends had finished the entire museum and I was still with the D50 at the entrance! 😀

Can anybody confirm that there are actually 2 genuine cars surviving? I had always believed that to be the case but several Lancia aficianados whom I know assure me that only one still exists.

As far as I know there are two original cars. One is in the National Museo dell Automobile…formerly the Biscaretti…in Turin, and the other one is in Lancia headquarters. I believe they may both belong to Lancia.

Ed

Thanks Ed! I now have a reference if I “lock horns” with my Lancia mates! 🙂

Regards

Alan

Best looking F1 car of all time. saw one at the Ferrari museum a few years ago. It was the highlight of the museum.

I think Ed’s memory confused Alberto Ascari with Eugenio Castellotti, for it was he who wore a yelow T shirt at times. The D50 was a wonderful concept. They looked wonderful at Silverstone in 1956 even after Enzo’s men had butchered them a little!.

Much enjoyed Ed’s story on his dream drive. Anything that Jim Stokes and his men prepare will be a delightful drive one way or the other. I think this earlier representation of the D50 was a trickier beast in period to master than the later, much worked upon Ferrari version. Certainly the short megaphones on the D50A make a more glorious din than the long pipes of the D50. Racing the D50A at the Revival I’ve found the car at something like 9/10ths. to be delightfully stable. Turns in nicely in the quick corners and puts the power down with no twitching about. The brakes are fine for the first few laps and then need some care. The object being to let everyone see, hear and smell the machine rather than squeeze the last drop of competition juice out of it. Having these built up machines is the only way that any of us would have got a taste of what we all missed for real so much kudos to the instigators and builders. You may know that the several engines and some 7 gearboxes used in the reincarnations were about to be scrapped in early 1971 when I was at the factory attending to the upgrade of of a 512S to M spec. for Le Mans that year.