By Roberto Motta

All photos by Renault Internal / Press

The record

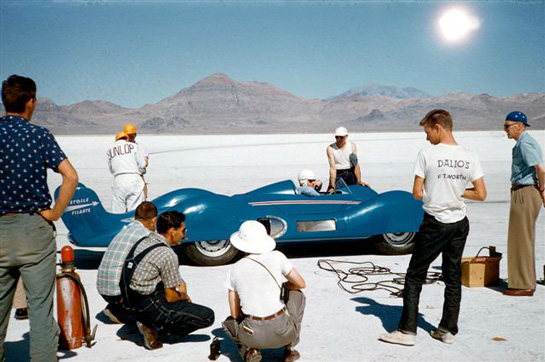

On August 17th, Albert Lory, his team and the French streamliner embarked on a airplane for the U.S.A. At the same time the U.S.A. subsidiary of Renault was mobilized under the leadership of Robert Lamaison, director of Renault U.S.A.

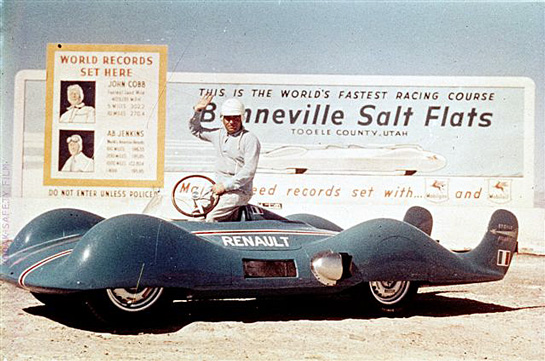

When the ‘Etoile Filante’ arrived in the USA, the entire team was moved to Wendover, Arizona, where the car was tuned for optimum conditions on the Salt Flats. Then, on September 4th, the ‘Etoile Filante’ was transported, for 15 miles, ‘on a beautiful scarlet Ford pickup’, to Bonneville Salt Flats, where the Renault’s technical team, the official timekeepers, and a few dozen people who gravitated around the project were eagerly awaiting the French comet.

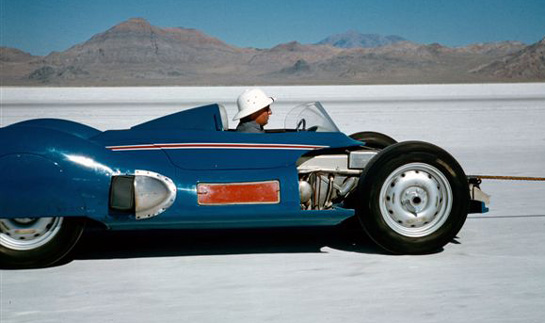

When the team arrived on the Salt Flats, the mechanics mounted the test tires, and the car, with Jean Hebert at the wheel, made some warm-up laps with a speed of 200 km/h. Everything was working right and the track conditions were perfect.

After a short briefing the mechanics mounted the high speed tires, and Jean Hebert got down into the cockpit: everything was under control.

The team was ready for the challenge.

A few minutes later, the AAA and FIA timekeepers were in their places and the ‘Etoile Filante’ left the line. The first timed run was at 220 km/h, another at 250, then at the third attempt ‘Etoile Filante’ reached the speed of 300 km/h.

The following day, September 5, in the early morning, the Etoile Filante was ready for more runs on the salt. In the first attempt achieved 310 km/h, and during the second run, Jean pushed up the engine to the upper limit of the turbine, 36000 rpm and 650°C for the turbine blades, and was able to run at 320 km/h. For the third run, the Renault was up to 322 km/h, while the last attempt reached 320 km/h before the overheating of the gear reduction unit stopped the adventure.

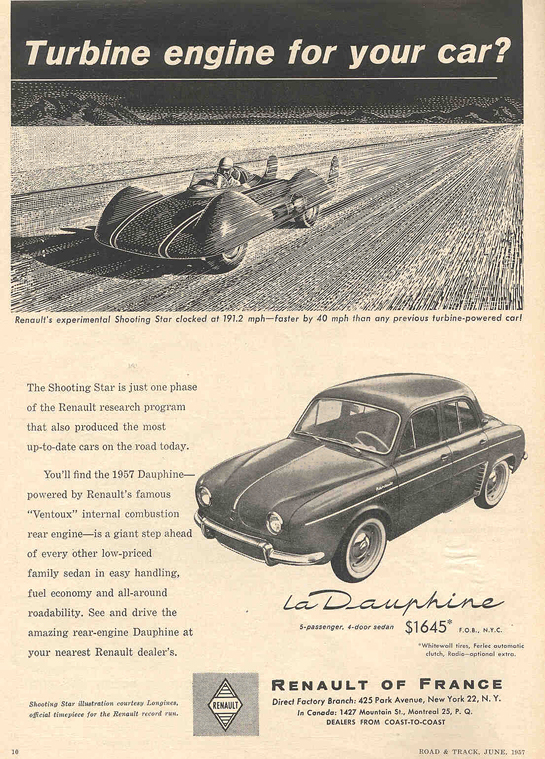

However, during the test, the timekeepers had some problems, and the chronometers were not working for runs in either direction. Therefore during the test the ‘Etoile Filante’ was officially clocked an average speed of 306.905 km/h over one kilometre, and 308.9 km/h (192.5mph) over five kilometers. The higher speed runs were not counted. Nevertheless, Renault and the Turboméca’s turbine easily set a new world record in its category, gas-turbine powered cars with weight of less than 1000 Kg.

The Shooting Star set a new record for its class at 192.5 mph for over five kilometers. Unofficially the Renault was timed at 322 kmh, or 200 mph.

It is a record that still holds.

After the records

Following this success, the car went on to the Montlhéry track, in order to be driven by great drivers and journalists, including Juan Manuel Fangio, Harry Schell and Jean Behra. Bernard Cahier was one of the lucky journalists to get behind the wheel of the Shooting Star. In a report to Road & Track in November 1957, he wrote that he quickly took it up to 130 mph on the bankings, amazed at the smooth and rapid acceleration. “I have tried many fast sports cars but the turbine is something completely different, and I shall not forget the seemingly endless acceleration, especially at very high speeds.” Fangio agreed and was also “delighted and surprised by the Shooting Star‘s performance.”

Then ’Etoile Filante, appeared on Renault stands in auto shows all over the world. For a short time many people thought that the gas-turbine engine would be the way of the future, and some manufacturers were initially interested in this technology but rapidly shelved their projects. So, as the Fifties came to the end, so did the brief but sparkling history of automobile gas-turbines.

As the Turbine rolled to a stop at Montlhery in July of 1957, so ended the short but sweet life of Renault's Shooting Star.

Renault stopped the construction of the second car, and the ‘Etoile filante’ became an interesting part of the Renault collection, The Shooting Star was just that—a car which sped across the heavens at lightning speed, leaving vivid impressions and world records in its wake. And just as quickly, it disappeared, never to be heard from again.