By Roberto Motta

All photos by Renault Internal / Press

Part I Construction and Development

The post-war period saw a great development of the aerospace industry. In France, a little team of engineers decided to apply aeronautic technologies to a record car, and the result was the Étoile Filante (Shooting Star). It was a meteoric success….

From a little lump of clay a shooting star was born. Renault designers used both a windtunnel and experience to fashion the turbine streamliner.

In the early 1950s many designers and engineers on both sides of the Atlantic felt that the turbine engine could become the engine of the future. It featured the ability to use different fuels than just gasoline, had lower consumption costs and it was lighter than a piston engine because it did not need a clutch or transmission.

At the start of the decade, the British brand Rover constructed a rather boxy car they called the JET 1, and had shown that the turbine engine was able to propel a record car at a speed of over 244 km/h (152 mph). This raised interest in the Turbine around the world and France in particular. In October 1954, Joseph Szydlowski, founder of the French aeronautical turbine company Turboméca, decided to break the Rover’s record.

The Turboméca, had already created a little turbine engine for the ‘Alouette’ helicopters and for tanks. Szydlowski decided to propose a gas turbine automotive application to the Renault management.

Szydlowski, nicknamed by friends ‘Jojo la Turbine’, (Joe Turbine) explained to Renault’s CEO Pierre Lefaucheux, that the turbine engine could be used by the French company to build a new car capable of breaking the Rover’s speed record, thus exalting the French brand and of course the turbine engined car in the automotive industry.

Peter Lefaucheux, a true man of action, took up this challenge, and called three experienced engineers to develop the project: Fernand Picard, product engineering director, Albert Lory, an engine specialist and the designer of the 1927 eight-cylinder Delage Grand Prix car, and Jean Hébert, an engineer that divided his office with a steering wheel, as a tester.

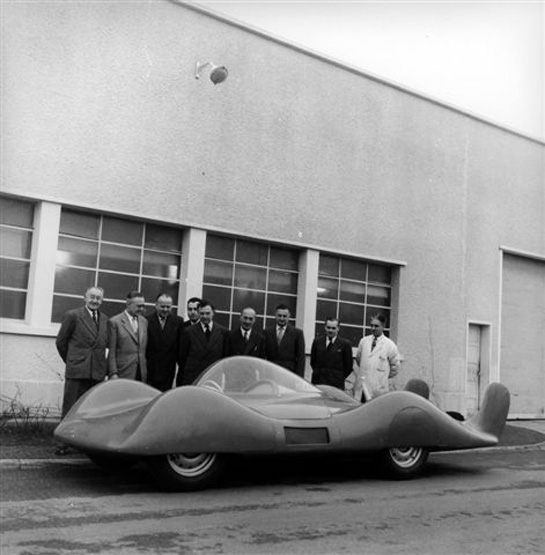

A proud crew with the Shooting Star. The engine was tested in April of 1956 and was ready for show in June.

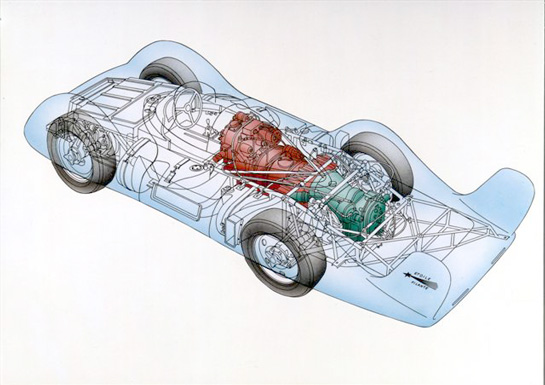

The project, with the internal identification number 7367, started in 1954 and involved the construction of a land speed record streamliner moved by a powerful turbine able to put out 270 hp at 28,000 rpm. It did not use a conventional gearbox but a three-speed gear reduction system that brought down the engine speed from 28000 rpm to 2500 rpm.

The engine was mounted in a conventional multi-tube frame with chrome molybdenum steel built under Renault supervision. Between the late 1954 and the early 1955, a 1/18 scale model of the car was constructed and tested in the wind tunnel. At the end of the studies what emerged was a car with a tubular frame, polyester body structure and twin aircraft-style stabilizers designed for stability, and almost five meters long. In the front, trailing-arm suspension and torsion-bar springs were employed and braking by four discs were used as the turbine would not provide the deceleration of a normal piston engined car. The car used a set of Dunlop tires and lightweight 17 inch magnesium wheels.

The first test

Construction went forward rapidly. On Sunday, April 29th, 1956, in the Technical Centre in Rueil-Malmaison, the staff was present for the first engine test; everything worked fine and the Turboméca’s turbine engines, Type Turbo 1, burning kerosene instead of gasoline pushed out 270 cv at 28000 rpm, and was able to reach the 35000 rpm for a short time.

Some days later, the car, without a body and with Jean Hebert at the wheel, underwent the first speed tests on the Renault’s track. After this test, the car received the new body and all the team went to Montlhéry where, during the speed test the car was able to register a speed of 200 km/h.

Some days later, on June 12th, the Project number 7367 officially received the name ‘Etoile Filante’, (in English ‘Shooting Star’), and the body was painted in French Racing Blue, adorned with red and white stripes. In addition, on the front bonnet and on the tail, a comet was painted to reflect its name.

Success on its first run; the Shooting Star went 136 mph on June 22. It was declared ready for the Salt Flats.

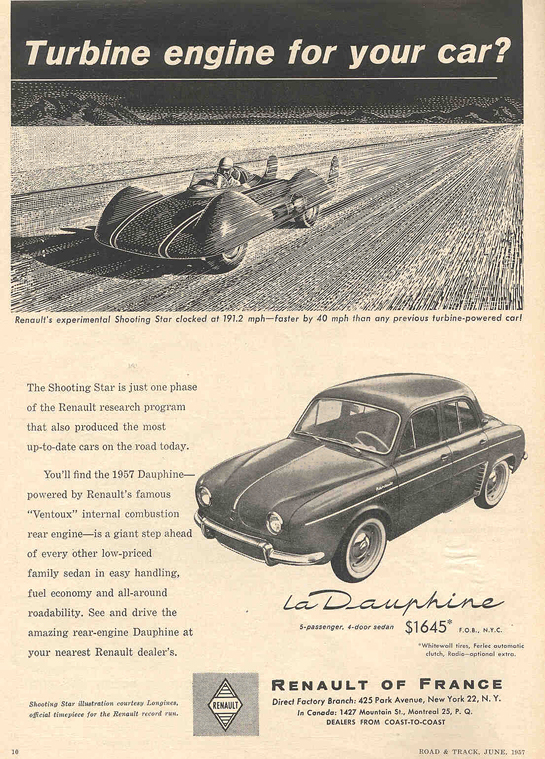

The ‘Etoile Filante’, was presented to the press, on Friday, June 22th, on the Montlhéry track. During the test session, the car was able to reach a speed of 220 km/h without hesitation. Rover’s record of 244 km/h was already in jeopardy. The same day, Pierre Dreyfus, the new president of Renault, said clearly that the car was not a project or a launching pad for a production car with a turbine engine, but only a prototype. It was to be a traveling laboratory that would allow the Renault brand to try to break the land speed record for gas-turbine powered cars.

But as many readers recall, in 1956, Renault launched a new small car, the Dauphine. Pierre Dreyfus knew that if they broke the record on the famous Bonneville Salt Flats, it would be an excellent way to promote the company and the new car in the USA.

I am a Renault fan. My father bought a Dauphine from an uncle of mine who had used it to carry his wife and three little ones.. perhaps a fourth on the way was sufficient mass to prove critical and prompt the sale our way. The Dauphine was our second car and was used sedately and properly by my mom and all too improperly and enthusiastically by me. Well, that car helped me come to expect good things of Renault. An interest in the early days of true “streamline” and speed record cars makes me doubly susceptible to this two part story. I love those radical lines and smooth (if somewhat lumpy) curves. The car is just a jewel that draws out the imagination and a smile. Thanks for the delightful work.